Quintus Curtius Rufus (historian)

Quintus Curtius Rufus was a Roman historian of the imperial era who wrote a nearly complete history of Alexander the Great in ten books.

Life

The dates of life of Curtius and the time of writing of his work are not known. Neither the author nor the work are mentioned in other ancient writings; only medieval manuscripts name Curtius as the author of the Alexander story. As a result, the dates vary from the Augustan period to Septimius Severus , and in some cases to Theodosius I. In modern research it is now assumed that Curtius lived in the 1st century AD; the vocabulary and literary style of his work also point to this period. The most likely dates of the work are in the reign of Emperors Claudius or Vespasian .

In the absence of external evidence, a passage is often used for dating in which Curtius compares the turmoil after Alexander's death with the civil war that ravaged the Roman Empire in his time. Like a “new rising star” ( novum sidus ), an unnamed princeps ended this conflict and founded a new dynasty. Which events Curtius alludes to and whether a civil war actually took place or whether a danger of civil war that was averted in good time should be hinted at, was assessed differently in research. Two approaches in particular have emerged recently: Most of the time, the passage is related to the murder of Caligula and the proclamation of Claudius . According to other researchers, the passage alludes to the civil war of the four-emperor year of 69 and Vespasian's accession to power. Still other researchers consider the passage to be a rhetorical topos that shows no allusion to the author's contemporary history and is therefore unsuitable for dating the author.

An upper limit for the dating is presumably formed by the references to the extent of the Parthian Empire , which suggest a formation before the displacement of the Parthians by the Sāsānids from 224 and probably also before the Parthian campaign of Emperor Trajan from 114.

Nothing is known about the author either. His attitude towards " barbarians ", Greeks and Parthians is often understood in research as that of a Roman; from various evidence it is concluded that he writes from the point of view of a city Roman of high social status. His attitude to the plebs , the simple people of the lower class, and the value system of the Historiae are read partly as reflections of a possible belonging to the nobility , partly as typical of a homo novus , i.e. the first of a family to hold a high office . Tacitus and Pliny mention a politician of the same name who was homo novus under Tiberius Praetor , held the office of a suffect consul in 43 , later went as a legate to the province of Germania superior and finally died as a proconsul of the province of Africa . Suetonius, in turn, testifies to a rhetorician of this name from the time between Tiberius and Claudius. Whether the author of the Alexander story is identical to one of these people or to both remains uncertain and is considered dubious in recent research.

plant

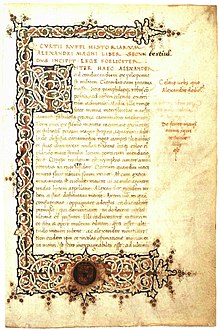

Curtius wrote a ten-book “History of Alexander the Great” ( Historiae Alexandri Magni Macedonis ) in Latin , of which the first two books have been lost. Parts of books 3, 5, 6 and 10 are also missing. It is nevertheless the only more comprehensive Latin historical work on Alexander that has come down to us more or less completely. The remaining part continues with the report on the year 333 BC. And the legend of the Gordian knot and ends with the death of Alexander and an outlook on the conflicts over his succession. Curtius based his presentation mainly on the Alexander story of Kleitarchos . Other sources include the universal history of the Timagenes of Alexandria and the Alexander story of Ptolemaios , which, like the work of Kleitarchos, are lost. Curtius may also have used Callisthenes , Aristobulus and - for the events in "India" - Nearchus .

The historical work that the research assigns to the so-called Vulgate tradition of the Alexander historians is strongly rhetorical; Numerous speeches, which are supposed to illuminate a problem from several sides, are put into the mouths of the protagonists by Curtius. The work tends to be dramatized; partly it resembles a novel , which is also due to Curtius' main source Kleitarchos, and takes up elements of the biography . The Alexander story by Curtius is still of value as a historical source, as it provides many details that are ignored in the other Alexander sources and presumably sticks closely to the first generation of Alexander historians. The work is literarily successful, even if Curtius' literary abilities in research have long been underestimated.

The work is strongly oriented towards the person of Alexander. While Alexander is still shown positively in the first half of the work, Curtius describes his character decline from the sixth book. In the second pentad he judges Alexander negatively. Corrupted by his successes, the Macedonian king turned into an oriental despot; his tyrannical traits and vices ( vitia ) outweigh his virtuous dispositions ( virtutes ) more and more clearly. Curtius particularly emphasizes affect as a driving force behind Alexander's actions. In a final appreciation, however, he also emphasizes his virtues such as greatness of mind, tolerance and courage, and attributes Alexander's vice to his youth and fate. With his picture of Alexander Curtius wants to act morally instructive - also with regard to his own time and the empire.

reception

Curtius was little read in antiquity and therefore had no effect. Pseudo- Hegesippus , who wrote a Latin adaptation of the Jewish War by Flavius Josephus around 370, only seems to have used Curtius in late antiquity . The early medieval Liber monstrorum de diversis generibus could also refer to his Alexander story . It was not until Einhard , the biographer of Charlemagne , that linguistic correspondences were found that indicate that the work was used in Carolingian times. The oldest of the 123 surviving Curtius manuscripts also date from the 9th and 10th centuries . John of Salisbury recommended reading Curtius. On the basis of his Alexander story, the Middle Latin poet Walter von Châtillon wrote the Alexandreis between 1178 and 1182 , an epic in ten books that was read in schools and has survived in more than 200 manuscripts; in the 13th century, the popularity of the Alexandreis outstripped the effect of their original. From the 15th century, Curtius became more widespread and was increasingly imitated stylistically. The first translations were made at the same time, and the first print edition followed in 1470 .

With the advent of the historical-critical method , Curtius was held in low esteem. Especially in German-language research, Curtius was judged very negatively as a historian and writer, while his information was placed in France with greater trust. The more recent research assigns it more weight again, despite several unreliability. Although he cannot replace the “more objective” Alexander historian Arrian , the work of Curtius Rufus offers valuable material to supplement and correct the positive Alexander image in Arrian.

Editions and translations

- Q. Curtius Rufus: Historiae (= Bibliotheca scriptorum Graecorum et Romanorum Teubneriana 2001). Edited by Carlo M. Lucarini, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-020116-1 (critical edition).

- Q. Curtius Rufus: History of Alexander the Great. Latin and German . Introduced, revised after the translation by Johannes Siebelis and commented on by Holger Koch and Christina Hummer, 2 volumes, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-18643-3 (with detailed introduction).

- Quintus Curtius Rufus: Alexander story. The story of Alexander the great . Translated by Johannes Siebelis, Phaidon, Essen / Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-88851-036-8 .

- Quintus Curtius Rufus: The History of Alexander . Translated by John C. Yardley, introduced and commented on by Waldemar Heckel, Penguin , London a. a. 2004.

- Curtius Rufus: Histories of Alexander the Great. Book 10 . Translated by John C. Yardley, introduced and commented on by JE Atkinson, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2009, ISBN 0-19955-762-4 .

Comments

- John E. Atkinson: A commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus' Historiae Alexandri Magni. Books 3 and 4 . JC Gieben, Amsterdam 1980, ISBN 9-07026-561-3 .

- John E. Atkinson: A commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus' Historiae Alexandri Magni. Books 5 to 7.2 . AM Hakkert, Amsterdam 1994, ISBN 9-02561-037-4 .

literature

- Michael von Albrecht : History of Roman literature from Andronicus to Boethius and its continued effect . Volume 2. 3rd, improved and expanded edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-026525-5 , pp. 916-926

- John E. Atkinson: Q. Curtius Rufus 'Historiae Alexandri Magni' . In: Rise and Decline of the Roman World II, 34,4, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, pp. 3447–3483, ISBN 3-11-015699-7 .

- Elizabeth Baynham: Alexander the Great. The unique history of Quintus Curtius . Ann Arbor 1998.

- Joachim Fugmann : On the problem of dating the ›Historiae Alexandri Magni‹ of Curtius Rufus . In: Hermes 123, 1995, pp. 233-243.

- Holger Koch: One hundred years of Curtius research (1899–1999). A working bibliography . Scripta Mercaturae, St. Katharinen 2000, ISBN 3-89590-103-2 .

- Robert Porod: The writer Curtius. Tradition and Redesign: On the Question of the Autonomy of the Writer Curtius . DBV-Verlag, Graz 1987, ISBN 3-7041-9035-7 .

- Werner Rutz: On the narrative art of Q. Curtius Rufus . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World II, 32.4, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1986, pp. 2329–2357, ISBN 3-11-010840-2 .

- Hartmut Wulfram (ed.): The Roman Alexander historian Curtius Rufus. Narrative technique, rhetoric, figure psychology and reception. Vienna Studies Supplement 38. Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-7001-7864-4 .

- Edmund Groag : Curtius 30 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IV, 2, Stuttgart 1901, Col. 1870 f. (outdated)

Web links

- Literature by and about Quintus Curtius Rufus in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Quintus Curtius Rufus in the German Digital Library

- Historiae Alexandri Magni at LacusCurtius (after the Teubneriana by Theodor Vogel 1880)

- Historiae Alexandri Magni at The Latin Library

- Translation by Curtius 10.6-10

- Jona Lendering: Quintus Curtius Rufus . In: Livius.org (English)

Remarks

- ↑ Atkinson (1998), pp. 3453, 3473.

- ^ Atkinson (2009), pp. 2–9 (for a compilation of the tenth book in Claudian times), Baynham (1998), pp. 201–219, Atkinson (1998), pp. 3451–3455, provide overviews of the question of dating and Atkinson (1980), pp. 19-50.

- ↑ Curtius 10: 9, 1-6; Another digression, which is based on dating, alludes to a long period of peace in the city of Tire , Curtius 4: 4, 21.

- ↑ A summary is provided by Baynham (1998), p. 206 f.

- ↑ For example Fugmann (1995), who pleads for Vespasian based on intertextual references to Titus Livius , or James Robertson Hamilton: The Date of Quintus Curtius Rufus . In: Historia 37, 1988, pp. 445-456, which, based on suspected echoes in Seneca, gives preference to dating under Claudius.

- ↑ Curtius refers to the Parthians in about 5,7,9, 5,8,1 and 6,2,12; Atkinson (1998), p. 3452 f., Baynham (1998), p. 202 f.

- ↑ On this Atkinson (2009), p. 9 f. with older literature.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales 11: 20-21; Pliny, Epistulae 7,27,1-3; see Fugmann (1995), p. 243, note 34 with further literature.

- ↑ Sueton, De rhetoribus 33rd

- ↑ For an overview of the author's question see Atkinson (1998), p. 3455 f .; Atkinson (2009), p. 13 f. Atkinson does not exclude the identification with the rhetor Curtius, not least because of the stylistic proximity of the Historiae to the eloquence of the imperial era.

- ↑ The title varies in the handwritten tradition.

- ↑ For the sources, see Baynham (1998), pp. 57-100.

- ↑ Curtius 10: 5, 26ff.

- ↑ For the description of Alexander in Curtius see Baynham (1998), pp. 132–164 (first pentad) and pp. 165–200 (second pentad).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Curtius Rufus, Quintus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1st century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1st century or 2nd century |