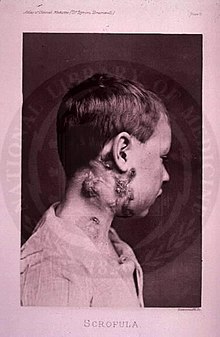

scrofula

Skrofulose (also Skrofeln , from Latin scrofula "neck adenoma"), also known as Scrofuloderm , is the historical name of a skin disease. The most likely cases of skin tuberculosis .

Term and Symptoms

After Dornblüths clinical Dictionary (1927) is at Skrofulose or Skrofeln an older term that has been used by's then usage in two overlapping meanings: on the one hand for a "exudative diathesis ", ie a constitutional tendency to insignificant stimuli to react to chronic inflammation, which was regarded as a preliminary stage, by some authors also already as a form of tuberculosis , on the other hand for tuberculosis in childhood with chronic inflammation of the lymph glands, skin, mucous membrane, bones.

In the Middle Ages, the term “scrofula” was used to describe an extensive clinical picture that also included various other neck and face diseases that also occurred in adults and were probably endemic in some areas . In today's terminology , the term scrofula is no longer used. As a remedy national medicine was Braunwurz which therefore the generic name Scrophularia received.

Healing rituals

As early as the 11th century, kings were believed to have miraculous abilities. Robert II of France is said to have had supernatural healing powers, but Eduard the Confessor is also said to have wonderful healings. From around the 13th century until the early modern period , there was a notion in France and England that the rightfully anointed king could heal scrofula by the mere laying on of hands ("the king's evil"). A corresponding healing ritual was also part of the coronation rites in both countries and was practiced regularly, at times even daily, on sick people who often traveled specially from far away areas of the kingdom. The king, gifted with the power of healing, was also called a thaumaturge . In France, the visit to the grave of St. Markulf after the coronation played an important role since Louis X.

When James I ascended the English throne in 1603 and founded the Stuart dynasty there, he initially rejected the tradition, which appeared unprotestant, Catholic or superstitious due to the belief in miracles working, and accepted it only reluctantly by sublimating the effect as prayer pointed. After the Stuart Restoration in 1660, Charles II used the laying on of hands particularly intensively to demonstrate the sacred dimension of royal rule (his father and predecessor had been executed in 1649) as restored; several tens of thousands, perhaps up to 100,000 of his subjects (two percent) he laid hands on during his reign. The skeptical Orange Wilhelm III. , who became King of England after the expulsion of the Stuart James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, refused the ritual. The only time he condescended to such a touch, he did it with the words: "God give you better health and more understanding." Queen Anne took up the ritual again, her successor George I (1714-1727 ) however, ended it for good because he found it "too Catholic". In France it was practiced for the last time in 1825 for the coronation of the Restoration King Charles X (1824–1830).

literature

- Marc Bloch : The miraculous kings. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44053-3 (first German translation of the classic mentality history Les rois thaumaturges from 1924; review ).

- David C. Douglas: William the Conqueror. 2nd Edition. Munich 1995, ISBN 3-424-01228-9 , p. 258 f.

- Peter Gienow: The scrofula, the forgotten miasma (= Miasmatic series of publications. Vol. 9). Peter Irl, Buchendorf 2007, ISBN 3-933666-42-2 .

- Walter Schaich: Tuberculosis. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid 1961, p. 291 f.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Skrofulose and Skrofeln in Roche Medical Dictionary

- ^ Skrofulose, Skrofeln in: Otto Dornblüth: Clinical Dictionary, 13./14. Edition, 1927

- ↑ Robert Ködel: Explanation of terms: scrofula. In: Allgemeine Homöopathische Zeitung. 255, 2010, p. 13, doi : 10.1055 / s-0029-1242580 .

- ↑ Raymon Crawfurd: The King's Evil. Clarendon, Oxford 1911, pp. 82 f. ; Stephen Brogan: The Royal Touch as Adapted by James I. In: History Today . Vol. 61, 2011, No. 2, pp. 46-52.

- ↑ Ronald G. Asch : The Stuarts. History of a dynasty. Beck, Munich 2011, p. 77 .

- ↑ Sigmund Freud: Totem and Tabu. In: Questions of Society - Origins of Religion. Study edition. Vol. 9. Frankfurt am Main 1974, p. 334.

- ↑ James G. Frazer: The Magic Art, and the Evolution of Kings (= The Golden Bough - a Study in Magic and Religion. Vol. 2). 3. Edition. Mc Millan, London 1911, pp. 368-370.