Conquest of Wales by King Edward I.

The conquest of Wales by King Edward I was the final conquest of the Welsh principalities by the English King Edward I between 1276 and 1283.

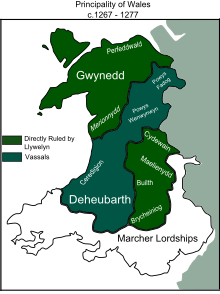

Wales under the Treaty of Montgomery

In 1267 between the English King Heinrich III. and the Treaty of Montgomery , signed to the Prince of Gwynedd, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd , Llywelyn was recognized by the King of England as head of the Welsh princes and as Prince of Wales . With that, Llywelyn had reached the height of his power. In return he had to pay homage to the English king as overlord and pay him the enormous sum of 30,000 marks . In the treaty, however, not all points of contention between the Welsh princes and the Anglo- Norman Marcher Lords had been resolved , so that there were several conflicts over the next few years.

Border conflicts with the Marcher Lords

The dispute over control of Maelienydd, which was claimed by Roger Mortimer , had not been resolved in the treaty. Roger Mortimer finally renewed his castle Cefnllys Castle there.

Another conflict arose in the south-east Welsh Glamorgan over the question of sovereignty over the Welsh Lords of Gwynllŵg and Senghenydd , who had previously been under the sovereignty of the Lord of Glamorgan. The Treaty of Montgomery had generally stipulated that the local Welsh barons should pay homage to Llywelyn. However, who exactly now belonged to these barons had not been precisely defined. Gilbert de Clare , the Lord of Glamorgan, had deposed and captured the Lord of Senghenydd in 1267. In 1268 he began building the mighty Caerphilly Castle and also drove out the Lord of Gwynllwg. Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, however, considered himself the patron of the Lords of Senghenydd and Gwynllwg after the Treaty of Montgomery. In 1270 he invaded Glamorgan and destroyed the Caerphilly Castle, which was under construction, but ultimately had to withdraw from Glamorgan and Gilbert de Clare was able to complete the castle.

The third source of conflict was Brecknockshire , which had been occupied by Llywelyn in 1262. In 1264 Roger Mortimer had been made Lord of Brecknockshire, but he had not had the means to drive Llywelyn out. In addition, Humphrey de Bohun, 2nd Earl of Hereford , whose son had acquired the rule in 1241 by marriage, did not give up his claims. From 1272 he tried to gain control of the rule through increased raids.

Conflicts within the Welsh principalities

Llywelyn himself had to enforce his supremacy over the smaller Welsh principalities partly by force. From Brecknockshire and Elfael in 1271 he demanded the position of hostages. To consolidate his rule over Cedewain, he began building Dolforwyn Castle in 1273 . The strategically located castle threatened Roger Mortimer's rule in Mid Wales, the royal castle Montgomery Castle and Welshpool with Powis Castle , the residence of Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn , Lord of Powys Wenwynwyn . Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn planned the murder of Llywelyn with Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd . In 1274, Llywelyn exposed the conspiracy and immediately occupied Powys Wenwynwyn. Gruffydd and Dafydd fled to England, but made several raids on the border areas with Wales as a result.

Llywelyn's conflicts with the Church

In 1274, Llywelyn started a conflict with Anian , the Bishop of St Asaph, trying to get a share of church fines. The Dominican Anian, bishop from 1268 to 1293, resisted violently and turned to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the English king and the Pope. So a dispute over money turned into a major dispute over church freedoms and ultimately led to a weakening of Llywelyn's position. Edward I confirmed the old rights of the diocese in November 1275 and January 1276, and Anian attended the royal meeting in November 1276, in which Llywelyn was condemned as a rebel. Llywelyn tried to buy up the rights of the bishop in early 1277, but the bishop came under royal protection, followed by the bishop of Bangor .

The dispute over the homage to the new king

In 1272 Heinrich III. died, and his son and successor Edward did not return to England from his crusade to Palestine until August 1274 . The Marcher Lords' violations of the Treaty of Montgomery seemed to Llywelyn like a single attack on his rule. He stopped his payments to the king in 1274, stating that the Marcher Lords were occupying territories he was entitled to, and refused to pay homage to the new king until the king decided on his complaints about violations of the Treaty of Montgomery. He refused to pay homage in January 1273 after the death of Henry III, he was not present at Edward's coronation in August 1274, and between December 1274 and April 1276 he did not obey five further requests from the king, not even when he did so in August 1275 traveled to Chester on the Welsh border. In contrast to Llywelyn, Edward I saw the Prince of Wales not as a sovereign prince, but as one of his larger vassals, who was subject to English law. Accordingly, he viewed the requested homage as a fundamental recognition and as a bond of a vassal to him, the refusal he viewed as a rebellion. In his last three summons, the King ordered Llywelyn to go to Westminster or Winchester , but in the end he no longer confirmed a safe conduct for him . To this end, Llywelyn tried in 1275 to marry Eleanor , who lived in exile in France , the daughter of Simon de Montfort . The king saw the planned wedding of the daughter of his mortal enemy Montfort with the rebellious Prince of Wales as a provocation, so he had Llywelyn's bride intercepted and captured on her crossing to Wales in the winter of 1275/76. The capture of his bride, the admission of the rebels Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn and Dafydd ap Gruffydd in England, in turn, reinforced Llywelyn's distrust of the king, so that he feared that he would be captured on a trip to England to pay homage. After further unsuccessful negotiations, the king decided in April 1276 to subjugate his stubborn vassals by force and finally declared him a rebel on November 12, 1276.

Campaign from 1276 to 1277

The king's campaign to subjugate Llywelyn was carefully planned and well coordinated. He followed the pattern of the campaigns of King John in 1211 and his father Heinrich III. from 1241 and 1245. For his campaign, Edward I could rely on broad support from the Marcher Lords, who now saw their chance to conquer or retake Welsh territories. The king gathered three armies at Chester, Montgomery, and Carmarthen in the spring of 1277 .

The army leader in Carmarthen, Payn de Chaworth was able to induce the most important lords of the House of Dinefwr to give up in South West Wales , who surrendered to him in April and May 1277 in the hope of preserving the territories of their relatives and neighbors as a reward for their submission. Chaworth occupied Dinefwr Castle , the old residence of the Princes of Deheubarth, and then quickly occupied Ceredigion . He was eventually replaced by Edmund of Lancaster , the king's brother, who began building Aberystwyth Castle on July 25, 1277 . The royal forces from Chester quickly occupied Powys Fadog, where the Welsh garrison at Dinas Bran set the castle on fire before it could fall into English hands. In Mid Wales, Llywelyn's new castle at Dolforwyn surrendered to Roger Mortimer's troops after an eight-day siege, and construction of a new castle began in May in occupied Builth .

The king called his feudal army to Worcester for July 1st, and by the time he and his army appeared at Chester in July 1277, Llywelyn's allies were already defeated or surrendered. In addition to the knights of his household, the king had raised an army of over 15,600 foot soldiers. The king led his army westward in small stages along the coast of North Wales. He had about 1,800 woodcutters cut wide aisles in the woods, so that his army could advance to Gwynedd without danger by ambushes. In Flint and Rhuddlan he began building castles to secure his conquests. On August 29th the royal army reached Deganwy on the Conwy . There he awaited the response from his fleet, which he had sent to conquer the Isle of Anglesey . The fleet of 26 ships provided by the Cinque Ports had brought 2,000 soldiers to the island under the command of Otton de Grandson and John de Vescy , then 360 English workers brought in the grain harvest there, so that Gwynedd was threatened with famine. The Welsh forces were trapped in the mountains of Snowdonia, and on September 12 the king moved his headquarters from Deganwy back to Rhuddlan. He could wait in peace, because the result of the campaign was devastating for the Welsh people. Llywelyn agreed to negotiate in September, and on November 9, 1277, a year after he had been declared a rebel, he accepted his defeat in the Treaty of Aberconwy .

Treaty of Aberconwy

In the Treaty of Aberconwy, Llywelyn had to give up large parts of his empire. Perfeddwlad east of the Conwy fell to the king, and he lost all territories in Southwest and Mid Wales, so that Gwynedd was again restricted to the territory of 1247. Except for five insignificant Welsh lords, Llywelyn lost supremacy over the Welsh lords. He had to pay homage to the king in Rhuddlan, and at the end of the year he had to travel to London and pay homage to the king again for Christmas 1277. He had to accept a fine of £ 50,000 for his rebellion, which was waived shortly afterwards. He had to provide his brothers with his own lordship. Edward I, however, allowed him to continue to use the title of Prince of Wales and gave his youngest brother Dafydd, who had lived in English exile after his conspiracy, a rule in the English-occupied Perfeddwlad.

However, Llywelyn does not consider the Aberconwy Treaty a final defeat. The loss of his sovereignty as Prince of Wales weighed heavily on him and English courts treated him as a royal vassal to answer in Montgomery or Oswestry. Still, he kept the terms of the treaty, and in October 1278 the king released the Welsh hostages and allowed Llywelyn to marry his bride, Eleanor. As a result, however, there were again conflicts between the Welsh and the English and their Welsh allies. The Welsh Lords of Ceredigion, Deheubarth and Powys Fadog complained bitterly about the loss of their independence. The English settlers in Flint , Rhuddlan and Aberystwyth abused their trading privileges, and numerous Welsh suffered under the tyranny of Reginald Gray , Roger de Clifford and Roger Lestrange , who abused their rights with the tolerance of the king. Llywelyn got into a dispute with Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn over the possession of Arwystli . In his opinion, Arwystli was part of Gwynedd under Welsh law, while Gruffydd, as Marcher Lord, appealed to English law and claimed the area for himself. The king hesitated to make a decision about final ownership. In the next few years Llywelyn tried, similar to the beginning of the 1250s, to expand his power through secret agreements. However, his preparations were far from complete when his brother Dafydd began a rebellion in March 1282. However, unlike 1277, when Llywelyn ap Gruffydd fought for power, the 1282 rebellion was a struggle by the Welsh for their rights and freedom.

Edward I campaign to conquer Wales in 1282

In March Llywelyn's brother Dafydd conquered Hawarden Castle and took Constable Roger Clifford prisoner. On the same day, a Welsh force under Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Maelor of Powys plundered Fadog Oswestry in Shropshire . Over the next few days, Aberystwyth Castle and other castles in West and South Wales were conquered. The well-planned uprising came as a complete surprise to the British occupiers. Llywelyn ap Gruffydd stated that he had nothing to do with the preparation of the insurrection, but he soon took over the lead of attacks on Rhuddlan and Flint Castle.

The rebels' hopes that English rule in Wales would quickly collapse as a result of the uprising, however, was not fulfilled. Edward I reacted quickly, but this time, in contrast to his campaign of 1277, he planned the complete conquest of Wales and the expulsion of the princes of Gwynedd who were traitorous to him. His strategy for conquering North Wales was similar to that of the 1277 campaign: first, three military commanders appointed by him were supposed to put down the rebellion outside Gwynedds. With his main army he then wanted to advance along the north coast of Wales to the River Conwy. At the same time, an army was to land on the island of Anglesey, thus cutting off the Welsh people from their granary. After the areas east of the Conwy were again in English hands, the army from Anglesey was supposed to cross over to Gwynedd and the main English army should advance to Snowdonia .

Enormous costs were expended to implement this strategy, so that the English king was soon able to conquer Northeast Wales again with a superior army. The conquest of Anglesey was also successful, but the attack on the mainland failed in the battle of Menai Strait . Llywelyn's position seemed hopeless, as Gwynedd was threatened by British armies in the north, east and south. After an attempt at mediation by the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Pecham , had failed, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd made an advance to Mid Wales to induce the local Welsh to revolt and thus build a second front. However, his force was provided there by an English army, and Llywelyn was killed on December 11th at the Battle of Orewin Bridge .

After his death, Dafydd took over the leadership of the Welsh resistance. Edward I, however, let his army advance further into Snowdonia. Most of the Welsh allies had surrendered, and on April 25 the occupation of Castell y Bere , the last major Welsh base , surrendered . The fugitive Dafydd was finally captured on June 21, 1283, wiping out the Welsh resistance.

After the English conquest

The captive Dafydd was convicted of treason in Shrewsbury and brutally executed. On March 19, 1284 Edward I issued the statute of Rhuddlan . The law declared the conquest of Wales complete and the conquered Gwynedd was placed under the rule of the king as the Principality of Wales . English Common Law was introduced in the principality, but the baronies of the Welsh Marches retained their independence. To secure the English rule, the king continued his castle building program and built an "iron ring" of castles around Gwynedd.

Most of the Welsh lords were evicted from their lands, with few allowed to keep their estates. Of the Welsh princes only Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn of Powys Wenwynwyn and Rhys ap Maredudd in Deheubarth could keep their territories as feudal lords under the rule of the king. Rhys ap Maredudd, who felt he was being treated unfairly, rebelled unsuccessfully against English rule in 1286, whereupon his territory was quickly conquered. A nationwide Welsh revolt arose against oppressive English rule and high taxation in the autumn of 1294 , but this was suppressed by the summer of 1295.

literature

- Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2

- David Walker: Medieval Wales. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990, ISBN 0-521-32317-7

Individual evidence

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 326

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 323

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 329

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 327

- ^ David A. Carpenter: The struggle for mastery. Britain, 1066-1284. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003. ISBN 978-0-19-522000-1 , p. 503

- ^ David Walker: Medieval Wales . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990. ISBN 978-0-521-31153-3 , p. 128

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 341

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 348

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 343

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 348

- ^ Rees R. Davies: The Age of Conquest. Wales 1063-1415. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-820198-2 , p. 348