Edgar (England)

Edgar (also: Eadgar, Ædgar, Adgar, Etgar, Eadgarus, Edgarus, Ædgarus etc .; * 943/944; † July 8, 975 in Winchester ) was king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria from 957 to 959 . After the death of his older brother Eadwig , he became king of all England from 959 until his death .

His epithet pacificus , which John of Worcester first mentioned in the 12th century, was mostly translated as "the peacemaker" in older literature. In recent literature, the translation peacemaker ( peacemaker ) is increasingly preferred. The devastation of the Isle of Thanet in 969 on Edgar's orders and the unrest after his death indicate that "peace" was maintained during his reign through strict control and military presence rather than the "peaceful" character of Edgar. Presumably the demonstrated willingness to use violence was one of the reasons that no Viking raids or invasions took place during his rule . Erik Blutaxt , the last Viking king of the Kingdom of Jórvík , was murdered in 954 and another wave of attacks did not begin again until 980.

Life

Edgar's life is poorly recorded. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has only ten entries on him, and for most other contemporary and contemporary sources, the ecclesiastical reformers are more in the foreground than the king. The material of the chroniclers from the 12th and 13th centuries is not very illuminating, as it is mainly about legends embellished stories that have little more in common with the historical king than the name.

family

Origin and youth

Edgar was born in 943/944 as the youngest son of Edmund I (939-946) from the House of Wessex and his first wife Ælfgifu. His older brother was Eadwig . His mother died in 944 and was venerated as a saint in Shaftesbury Abbey , where her mother Wynflæd († around 950) was a nun. Edmund soon married Æthelflæd of Damerham. When his father Edmund died in 946, his stepmother married the Ealdorman Æthelstan Rota from Mercia. Edgar and Eadwig were thus in the mood of King Eadred (946–955), a brother of their father.

The unmarried Eadred gave Edgar for education to Ælfwynn († 986), the wife of Ealdorman Æthelstan Half-King of East Anglia. His grandmother Eadgifu , Edward the Elder's widow , also played an important role . She persuaded Eadred around 954 to hand over the dilapidated secular monastery of Abingdon to Abbot Æthelwald (around 954–963) and to convert it into a Benedictine monastery. Edgar was further educated in this monastery. He became familiar with the Benedictine Reform early on , which was to prevail in England during his reign.

Marriages and offspring

Edgar's first wife, Æthelflæd Eneda, is only known to be the mother of his son Eduard the Martyr . It is uncertain whether he had a Muntehe (full marriage) or Friedelehe with Wulfthryth, his second wife and mother of his daughter Eadgyth ( Edith von Wilton ) . Wulfthryth later became abbess of Wilton Monastery , which Eadgyth also entered. Wulfthryth and Eadgyth were later venerated as saints. Around 964/965 Edgar married Ælfthryth († 999/1001), the daughter of Ealdorman Ordgar (964–971) and widow of Ealdorman Æthelwald of East Anglia. From this marriage the sons Edmund († 971) and Æthelred were born.

Domination

Succession to the throne

King Eadred died in 955 unmarried and without leaving any descendants. He was succeeded as king by his nephew Eadwig, Edgar's older brother. Forever was unpopular. Even benevolent contemporaries accused him of being wasteful. When the 14-year-old Edgar came of age in 957, the empire was divided. Edgar was made King of Mercia and Northumbria , while Eadwig continued to bear the title of "King of the English". However, it cannot be ruled out that the division already took place in 955. This would suggest that Edgar signed a charter, albeit a questionable one, in 956 as a regulus (subordinate minor king ). The division appears to have been amicable in any case and should possibly only designate Edgar as Eadwig's successor. Only one difference of opinion is known between the brothers: In 956 Eadwig banished Dunstan , the abbot of Glastonbury Abbey . After a year of exile on the mainland, Dunstan returned to England and was installed by Edgar as Bishop of Worcester (957–959) and Bishop of London (958–960). The secular and ecclesiastical dignitaries known from charters, most of whom remained in office after Eadwig's death on October 1, 959, point to a geographical rather than political division.

After Eadwig's death, Edgar became sole king. He maintained good contacts with Ælfgifu, his brother's widow, and gave her larger estates as rex totius Brittanniae ("King of all Britain"). Before 973 he made her brother, the chronicler Æthelweard , the "Ealdorman of the western provinces", which probably means Wessex.

Royal court

Edgar's most influential counselor was his old teacher Æthelwald , whom he made Bishop of Winchester in 963 . Unlike his previous wives, Ælfthryth was also a force of power. Her family enjoyed Edgar's favor. He made her father Ordgar Ealdorman of Devon in 964, and her brother Ordwulf later became the chief adviser to his youngest son Æthelred. She maintained close contacts to Ælfhere († 983), the Ealdorman of Mercia, and his older brother Ælfheah, Ealdorman of Hampshire , who was probably Edmund's godfather.

In ecclesiastical politics , Edgar promoted the representatives of the Cluniascensic reform . Through his intervention, Dunstan , whom Edgar had already made Bishop of Worcester (957–959) and London (958–960) at the beginning of his reign , was replaced by the ousted Brihthelm in 959/960 Archbishop of Canterbury. Oswald became Archbishop of York in 971 without having to give up the bishopric of Worcester, which was preserved in 962. Æthelwine, the youngest son of Edgar's foster father Æthelstan Half-King , became Ealdorman of East Anglia after the death of his brother Æthelwald. Oswald and Æthelwine re-founded Ramsey Abbey as a Benedictine community. Numerous other monasteries z. B. Worcester, Westbury-on-Trym, Pershore, Peterborough, Ely, Croyland and Thorney were newly established or reformed. The surviving charters attest to the generous endowment of the Reformed monasteries with lands by Edgar. Edgar's former teacher, Abbot Æthelwald, praised Edgar for promoting the Benedictine Reform. Decades later, Archbishop Wulfstan II of York (1003-1023) wrote a poem of praise for Edgar.

legislation

Four of the surviving Old English legal codes are commonly attributed to Edgar. The authorship of the hundred ordinance (eg “Hundertschaftsgesetz”) is questionable; possibly it goes back to Eadred . This law regulates the legal and tax functions of the hundred , a subdivision of the shire .

Codices II and III are of unknown date and were probably promulgated together in Andover . Codex II deals with church taxes and private churches . The second part of Codex III is devoted to secular matters such as access to justice, the prevention of wrongful judgments and guarantees. Finally, provisions are made for the standardization of coins, dimensions and weights. Æthelstan (924–939) had already ordered something similar , but in the opinion of modern historians Edgar's reforms led to a unified monetary system, at least south of the tea .

The Codex IV, issued in Wihtbordesstan (unidentified place) in the 970s, is of particular importance . Edgar recognized the “good” legislation of the “Danes” in Northumbria because Earl Oslac was “always loyal” to him. Indeed, royal influence in the north was limited. The assimilation of the Kingdom of Jórvík , which had only been defeated in 952/954, was one of the most important tasks in the 950s and 960s and was not to be completed until the 11th century.

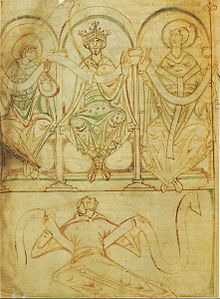

coronation

Edgar's coronation took place with great pomp on May 11, 973 ( Pentecost ) in Bath . Why the coronation took place so late is the subject of controversial discussions: some historians argue that Edgar was crowned as early as 960/961 and that this is a second coronation on the occasion of the attainment of the empire (supremacy) over the whole of Britain. Others argue that he reached canonical age for episcopal ordination at the age of 30. It is noteworthy that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in contrast to its predecessors, reports on the coronation at all.

Meet in Chester

According to sources, immediately after the coronation, Edgar drove his fleet to Chester , where six or eight kings submitted to him. According to a list held to be authentic by John of Worcester, a chronicler of the 12th century, these were Kenneth II (Scotland, 971-995), Máel Coluim I ( Strathclyde , 975-997) and his father Dyfnwal III. (941–971; † around 975), Maccus Haroldson ( Isle of Man and Hebrides ; † around 977), Iago ab Idwal ( Gwynedd , 950–979), his brother Idwal Fychan († 980) and his nephew Hywel ap Ieuaf ( 974 / 979-985). It is possible that the kings submitted to Edgar at different times during his reign and the event described is only a literary condensation. The kings are said to have rowed him in a boat across the river Dee as a sign of their submission . In the 960s, England was repeatedly the target of Scottish and Welsh attacks. The 973 meeting in Chester is therefore seen more as a "peace conference" of the powers involved than as "submission". The cession of the controversial Lothian in northern Bernicia by Edgar to Kenneth II can probably be seen in this context .

Defense policy

Even the contemporary Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Ælfric Grammaticus († 1020) highlight the strength of the English fleet, with which Edgar circumnavigated his kingdom every year as a show of power. Chroniclers of the 12th and 13th centuries even put the fleet at 3600 or 4800 ships, which is certainly an exaggeration.

Presumably, the organizational form of sipessocna, scypsocne or scypfylleð (about "ship district"), documented under his son Æthelred (978-1016) , according to which 300 hidas (farmsteads) had to pay for the maintenance of a ship, goes back to Edgar. How many of these sipessocna there were is unknown; the five known were owned by monasteries or dioceses; Oswaldslow ( Worcestershire ) in the Diocese of Worcester is the best documented. Edgar presumably also hired Vikings with their boats as mercenaries, which was not unusual at the time.

Death and succession

Edgar died unexpectedly on July 8, 975, aged 31 or 32, and was buried at Glastonbury Abbey . His eldest son Edward the Martyr succeeded him.

See also

swell

- Edgar's charters

- anonymous: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Online in Project Gutenberg (English)

- Ælfric Grammaticus : The Life of St Swithin . ( PDF, 44 kB, old English / English) at uni-duesseldorf.de

- Ælfric Grammaticus: Vita Æthelwoldi

- Annals of Ulster , The Annals of Ulster AD 431-1201 in CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts

- Æthelweard : Chronica

- John of Worcester : Chronicon ex chronicis

- Symeon of Durham : De Gestis Regum Anglorum (Deeds of the English Kings)

- Symeon of Durham: Historia ecclesiae Dunelmensis (History of the Church of Durham)

- Byrhtferth: Vita Oswaldi

- B .: Vita Dunstani

literature

- Donald G. Scragg (Ed.): Edgar, King of the English, 959-975: new interpretations (Publications of the Manchester Center for Anglo-Saxon Studies Vol 8), Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84383 -399-4 .

- Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1 ; esp. Sean Miller: Edgar . Pp. 158-159.

- Dorothy Whitelock : English Historical Documents 500-1042 Vol 1. Routledge, London 1996 (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0-415-14366-0 .

- Michael Lapidge, John Crook, Robert Deshman, Susan Rankin: The cult of St Swithun (Winchester studies), Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-19-813183-0 .

- Catherine E. Karkov: The ruler portraits of Anglo-Saxon England (Anglo-Saxon studies Vol 3). Boydell Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1-84383-059-7 .

- Barbara Yorke : Bishop Aethelwold: his career and influence . Boydell & Brewer, 1997, ISBN 978-0-85115-705-4 .

- Barbara Yorke: Wessex in the early Middle Ages (Studies in the Early History of Britain), Continuum, 1995, ISBN 978-0-7185-1856-1 .

- Pauline Stafford: Gender, family and the legitimation of power: England from the ninth to early twelfth century , Ashgate Publishing, 2006, ISBN 978-0-86078-994-9

Web links

- The Laws of King Edgar, 959-975 AD in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

- Ann Williams: Edgar (paid registration required). In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved February 15, 2012

- Edgar 11 in Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE)

- Edgar in Foundation for Medieval Genealogy

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Ann Williams: Page no longer available , search in web archives: Edgar (paid registration required). In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ Simon Keynes: Kings of the English . In: Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1 , pp. 514-516.

- ↑ Sean Miller: Edgar . In: Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1 , pp. 158-159.

- ^ RC Love: Eadgyth . In: Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1 , p. 150.

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Ælfthryth 8 in Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE)

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript D

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Charter S737 and page no longer available , search in web archives: Charter S738

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 959

- ↑ The Laws of King Edgar, 959-975 AD in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Charter S731

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Forever |

King of England 959–975 |

Edward the Martyr |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Edgar |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Eadgar; Ædgar; Adgar; Etgar; Eadgarus; Edgarus; Ædgarus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of Wessex and England |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 943 or 944 |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 8, 975 |

| Place of death | Winchester |