Franco-English War from 1202 to 1214

The Franco-English War from 1202 to 1214 , also known as the Anglo-French or Anglo-French War , was a long-term war between the Kingdom of England , whose king still had large fiefs in France at the beginning of the war , and the Kingdom of France . Through the war, which was interrupted several times by armistices, France was able to conquer and maintain large parts of the so-called Angevin Empire in France. The defeat in the war led to the War of the Barons in England and the conclusion of the Magna Carta .

background

With the conquest of England by William the Conqueror , the Duke of Normandy in northern France also became King of England. Apart from brief interruptions, Wilhelm's successors remained both kings of England and dukes of Normandy, making them nominally vassals of the kings of France. Through the marriage of the future English king, Henry II Plantagenet , who had inherited the French counties of Anjou , Maine and Tours from his father , with the heiress of the Duchy of Aquitaine , the Angevin empire came into being, which in addition to England and Normandy also grew through inheritance and marriage acquired possessions and thus large parts of France. The French King Philip II, who ascended the throne in 1180, therefore continued his father's policy of smashing the Plantagenet empire, which restricted the king's power . Henry II's son and successor Richard the Lionheart was able to defeat Philip II in a long war from 1194 to 1199, but fell shortly afterwards during a siege in southwest France. His brother Johann Ohneland became Duke of Normandy, King of England and was finally able to take control of the other French possessions against the opposition of Philip II, who supported John's nephew Arthur of Brittany . In the Treaty of Le Goulet , he was recognized by the French king in 1200, but in return had to recognize him as liege lord for his possessions in France.

Another outbreak of war

The peace between the two kings did not last long, however. The main cause of the renewed outbreak of war was Johann's refusal to respond to the complaints of the Lusignans , who were among the most powerful of his vassals in Aquitaine. The Lusignans then turned to the French king as their overlord. This admonished Johann first, as feudal lord, to listen to the complaints of his vassals. When Johann did not comply with this request, Philip II had to summon the English king to his court . Johann replied that as Duke of Normandy he had the old privilege of only meeting the French king on the border of his duchy. Philip II replied that John should answer not as Duke of Normandy, but as Duke of Aquitaine. When Johann further refused to answer for the complaints of his vassals, Philip II declared the English king a rebellious vassal in May 1202 and forfeited all of his fiefs in France.

Campaigns of 1202

Philip II started the war with an attack on Normandy. To this end, he knighted John's nephew Arthur of Brittany, who continued to raise his claim to his inheritance, in Gournai and enfeoffed him with John's French fiefs with the exception of Normandy, which he declared to be crown land . While Arthur attacked and plundered John's possessions along the Loire with Poitevinian nobles who rebelled against John's rule , Philip II and his army attacked the castles on the eastern border of Normandy. Johann trusted these mighty castles and led his mercenary army south to defend his possessions there. At Le Mans he received the news that his aged mother Eleanor was being besieged by Arthur and his allies in the castle of Mirebeau . With the help of his vassal Guillaume des Roches , he led his army on a forced march to Mirebeau, where on the morning of July 31st he completely surprised the rebels. With the help of the local Guillaume des Roches, he penetrated the city and was able to capture all the knights and leaders of the rebels. In addition to Johann's nephew Arthur, Gottfried von Lusignan , Hugo le Brun , Savary de Mauléon and over 200 knights were also captured. He had many of the knights brought to England to keep them in safe custody until the ransom was paid.

However, Johann failed to take advantage of this overwhelming victory. He fell out with Guillaume des Roches over the treatment of the prisoners. This soon joined together with Vice Count Amery de Thouars Johann's opponents. Their possessions in Anjou and northern Poitou now interrupted John's lines of communication and supply to Aquitaine. In the autumn of 1202 the Bretons conquered Angers , the old residence of Johann's ancestors. Johann concentrated his forces on Argentan in western Normandy, but became increasingly on the defensive. His reputation suffered further damage when over 20 of the knight trapped at Mirebeau occupied the keep of Corfe Castle in an attempt to escape , but then preferred to starve to death instead of surrendering again. The rumors about the fate of his captured nephew Arthur, whom he had brought to his home in Rouen , turned out to be even more momentous for Johann . From there he disappeared, probably in April 1203 Johann killed his nephew in anger or in a drunken state.

French conquest of Normandy from 1203 to 1204

In January, John's wife, Queen Isabella, was besieged at Chinon Castle. He broke off an advance led by him to Chinon after Robert, Count of Alençon in the south of Normandy, had changed sides. Johann himself was so convinced of the unreliability of his vassals in Normandy that he did not undertake a campaign in the summer of 1203. His wife Isabella was finally horrified by a contingent of mercenaries under Pierre de Préaux and brought to Argentan . Philip II, on the other hand, was able to advance along the Loire while the rebels from the Poitou attacked Aquitaine. Then Philip II resumed his attacks on the border castles of Normandy. First Conches was conquered, then the castle of Vaudreuil, defended by Robert FitzWalter and Saer de Quincy , suddenly surrendered . At the end of August the French began the siege of Château Gaillard , which blocked the Seine valley. A relief attempt on water and on land led by Johann and his confidante William Marshal failed with high losses. Johann then turned west and attacked Brittany , where he looted Dol . Suspicious of his barons in Normandy, Johann gave up and sailed from Barfleur to Portsmouth in England on December 5, 1203 .

In England Johann began to prepare for a new campaign in Normandy. At the beginning of March 1204, however, the French took by storm the Château Gaillard, which was considered impregnable. Instead of marching directly on Rouen, the heavily fortified capital of Normandy, Philip II led his army to the west of Normandy. In April Johann offered him an armistice, but Philip II demanded that he renounce all of his continental possessions. Philip II bypassed the border fortresses in the south of Normandy and advanced through the Orne valley into the center of the duchy. He conquered without much of a fight Argentan, while the leader of the mercenaries Lupescar defended Falaise capitulated after only one week. Lupescar now changed sides and joined Philip II. Then Philip II occupied Caen , the old capital of Normandy, without a fight , and as a result numerous barons in the area paid homage to the French king as their new liege lord. At the beginning of May a Breton army advanced west of Normandy, captured Mont-Saint-Michel and Avranches, and united with the French army at Caen. While a division of the army occupied the Cherbourg peninsula , the main French army advanced via Liseux to Rouen. With that, Normandy was effectively conquered. To prevent a senseless destruction of Rouen, Pierre de Préaux, the English commander of the city, agreed a thirty-day armistice with the French on June 1st. When it finally became clear that no relief army was coming from England, he capitulated before the end of the ceasefire on June 24th, which meant that Normandy was lost to England.

The reasons for the rapid loss of the duchy were complex. In addition to Johann's mistakes, there was also the fact that the grueling wars under his father and brother Richard the Lionheart had overwhelmed the duchy's finances. However, while Richard the Lionheart was still successful with his wars, his brother was ridiculed as an unsuccessful no-land or softsword . The French royal court of Philip II, on the other hand, had become the cultural and political center of France at the end of the 12th century, so that the ties between Normandy and England were broken. The cultures of Normandy and Norman England diverged, and the nobles began to feel more like French nobles than Norman. As a result, it turned out that in the defense of Normandy the resistance against the French attackers was only borne by Johann's mercenaries and the English knights and barons, so that Johann feared treason everywhere. According to contemporary chroniclers, Johann stayed mostly inactive during the attacks of Philip II because he lay in bed with his young wife Isabella for days. In fact, the records and evidence show that Johann was traveling back and forth without being able to effectively defend Normandy.

Consequences of the conquest of Normandy

During the war from 1202 to 1204, Johann had not only lost Normandy, but also Anjou, Maine and the county of Tours, whose nobles had defected to Philip II. After the death of John's mother Eleanor, who had been Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, on April 1, 1204, many barons of Aquitaine also paid homage to the French king, who entered Poitiers in triumph in August . Only parts of the Poitou with La Rochelle and Gascony , which was defended by Elias von Malmort, Archbishop of Bordeaux , remained in Johann's hands.

As a result of the conquest of Normandy, numerous Anglo-Norman barons who had fiefs in Normandy had to fear for these possessions. Philip II demanded the fiefdom of them, while Johann would treat them as a traitor in this case. Most tried to postpone the feudal oath by making payments, but in the end Philip II confiscated, with a few exceptions, the lands of the nobles who were in England and who had not returned at a specified time in the form of a general decree. In return, Johann proceeded in a similar way with the English lands of the nobles who were loyal to Philip II.

The long connecting routes to the remaining English possessions in south-west France, which led around Brittany, which was dangerous for seafaring and also hostile, as well as the threat to the south coast of England after France had conquered Normandy, showed that the ships of the Cinque Ports were not just for sea warfare more sufficient. The king therefore commissioned William of Wrotham to build up his own royal navy, this was the origin of the Royal Navy .

Failure of the English campaign of 1205

However, Johann never gave up his claims to the lost territories. At the end of March 1205, at a council meeting, he was able to get his English barons to agree to continue supporting him in the active defense of his possessions in France. So he was able to summon the tenth part of his feudal army to London for May 1st, so that it was available to him for the necessary defense of the empire. He tried so to get a smaller, more powerful army that he was available longer than the 40 days required by the fiefdom. Some of his troops, especially mercenaries under the command of his illegitimate son Geoffrey , he ordered to Dartmouth , the far greater part he ordered to Portsmouth. In June he assembled a large fleet off Portsmouth to cross over with his army to France. However, his English barons put forward numerous pretexts so that they would not have to follow him to France. Even William Marshal did not want to take part in the campaign, as he had just signed an agreement with the King of France that allowed him to keep his fiefdom in Normandy. Since Johann could not change his barons' minds, only a contingent of mercenaries set out for Poitou and reinforcements under William Longespée , the king's half-brother, to La Rochelle. The king had to cancel his planned main campaign, which was probably directed against Normandy. Due to the lack of relief, the isolated castles of Chinon and Loches had to surrender to the French siege troops by summer 1205.

English campaign of 1206

From April 1206, Johann prepared an expedition to southwest France to organize the defense of his remaining possessions there. At the beginning of June 1206 he sailed with his army to La Rochelle, which he reached on June 7th. Although the English barons had caused the campaign to fail in the previous year, a surprising number of his nobles accompanied him on this campaign. In La Rochelle, numerous nobles from Aquitaine joined him. Since his armed forces were still insufficient for a campaign of conquest, he first made several forays into Poitou, the majority of which had switched to the side of King Philip II. In a first foray, he horrified the city of Niort , which Savary de Mauléon thought was him. Then he turned briefly to the south, before he sailed to the mouth of the Garonne in July and made an advance from there on Montauban , which was a stronghold of his opponents among the nobles in southwest France. After 15 days of siege, he succeeded in conquering the city, considered impregnable, with the help of siege engines . In August he returned to Niort and made an advance eastward to Montmorillon . Aimery, the Vice Count of Thouars, who had been appointed Seneschal des Poitou by the French king, now went over to him. Johann now moved west to the border of Brittany in order to advance from there to Angers, the residence of his ancestors. After staying in Angers for a week, he moved further north to Le Lude before retiring to Poitou. The French King Philip II had called up his feudal army against his advance and had advanced to the Poitou border, but he did not undertake a counterattack. On October 26, 1206, the two kings concluded an armistice in which Philip II recognized the reconquest of large parts of the Poitou. The armistice was limited to two years and was overseen by a commission made up of four barons from both parties. Through the campaign, Johann not only regained large parts of the Poitou and secured Aquitaine, but also gained valuable experience in carrying out a sea-based operation.

Planned military campaign to France in 1212

In the next few years Johann took care of the administration of England. Conflicts with the Pope, the Welsh princes and Scotland prevented him from further campaigns against France. After successful campaigns against Wales and Scotland, Johann believed from 1211 that his possessions in France would soon be recaptured. He renewed his alliance with Count Rainald von Boulogne , which he had ended by the Peace of Goulet in 1200, and prepared a campaign to France for the summer of 1212. The rebellion of the Welsh princes, who, under the leadership of Llywelyn from Iorwerth, revolted against the expansion of John's supremacy over Wales, came as a surprise to him. After the rebellion turned out to be more serious than Johann had initially assumed, he called his land and naval forces, which he had gathered in Portsmouth , to Chester . There he learned that a group of the English barons had conspired against him, who even wanted to kill him during the campaign to Wales. Thereupon he canceled the campaign to Wales and turned against the rebellious barons.

Failed French invasion attempt in 1213

In return, the French King Philip II hoped that if he landed in England , he would receive support from the rebellious barons against John, who had been excommunicated since 1209 . In 1213 he therefore prepared an invasion of England. However, his vassal, Count Ferdinand of Flanders, demanded the return of two cities in return for his participation in the invasion, which he had previously had to cede to the king. Therefore, before setting out for England, the French king sailed with his fleet to Flanders in order to enforce his sovereignty over Count Ferdinand. While the French soldiers were attacking Ghent , the almost defenseless French fleet anchored off Damme was attacked on May 30th and 31st by the English fleet under William Longespée. The English were able to inflict a decisive defeat on the French fleet, so that the invasion attempt of the French king had failed.

English attack on France in 1214

The next year Johann planned to hit Philip II with a pincer attack on France. While he wanted to lead an expedition to Poitou himself, another English army was to unite in Flanders with the allied armies of the Roman-German Emperor Otto IV , the Count of Boulogne and other allies.

King John landed in La Rochelle in February 1214 . After initially making forays into the Limousin and Gascony, he marched through Poitou in May, where he first beat the Lusignan family and finally won them over with a promise to marry his daughter Johanna and Hugo X. von Lusignan . Then he turned north, conquered Nantes and was able to move into Angers again. While he was besieging the castle of Roche-aux-Moines north of Angers, the French Prince Ludwig appeared with an army in front of the castle. Johann's French allies abandoned him and fled, so that Johann finally cleared the battlefield himself without a fight and fled back to La Rochelle, which he reached on July 9th. The second part of Johann's war plan also failed. The army of William Longespée was able to unite with the allied armies, but then they were decisively defeated by the French troops in the battle of Bouvines on July 27th . King Philip II now advanced into Poitou, and on September 18, Cardinal Robert Curzon , of English descent, brokered a five-year truce between the two kings.

consequences

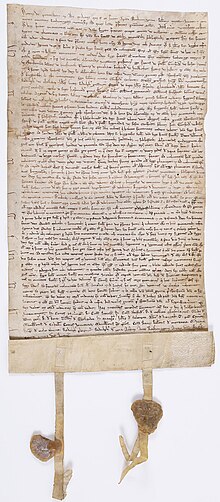

Johann retired to England in October 1214, where he found himself facing a noble opposition. He finally had to respond to the demands of his rebel barons and confirm their rights in the Magna Carta in 1215 . Nevertheless, a civil war ensued in England, in which the rebellious barons offered the English crown to the French Prince Louis. Ludwig landed in England on May 22, 1216 and was proclaimed king in London. He was able to quickly occupy large parts of the country, but Johann continued to resist. During a campaign to Central England, Johann fell ill with dysentery and died on October 18, 1216. His followers quickly crowned his nine-year-old son Heinrich as the new king. The regent William Marshal recognized the Magna Carta, whereupon numerous English barons switched to the side of the underage Heinrich. After several defeats, Prince Ludwig had to make the Peace of Lambeth in September 1217 , renounce his English claim to the throne and leave England.

After the armistice had expired, the now French King Louis VIII attacked the English possessions in south-west France in a new war in 1224 and was able to conquer them as far as Gascony. An attempted invasion by Heinrich III. in Normandy failed in 1230, in 1242 another campaign by the king in France failed due to the defeat at Taillebourg . After that, Heinrich III. no further campaigns against France and recognized in the Treaty of Paris in 1259 the loss of his family's possessions, but remained master of Gascon.

literature

- Wilfred L. Warren: King John . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978. ISBN 0-520-03610-7

- Guillaume-André de Bertier de Sauvigny: The history of the French . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1980. ISBN 3-455-08871-6

Individual evidence

- ^ Propylaea World History , Propylaea, Berlin 1961, Vol. 5, p. 452

- ↑ Wilfred L. Warren: King John . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978. ISBN 0-520-03610-7 , p. 76

- ↑ Trevor Rowley: The Normans . Essen, Magnus 2003. ISBN 3-88400-017-9 , p. 82

- ↑ Wilfred L. Warren: King John . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978. ISBN 0-520-03610-7 , p. 89

- ↑ Wilfred L. Warren: King John . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978. ISBN 0-520-03610-7 , p. 88

- ↑ Wilfred L. Warren: King John . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978. ISBN 0-520-03610-7 , p. 125

- ↑ Wilfred L. Warren: King John . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978. ISBN 0-520-03610-7 , p. 112