John Wycliffe

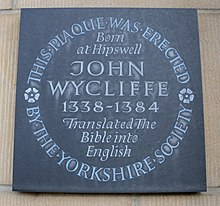

John Wyclif [ ˈwɪklɪf ], also Wicklyf, Wicliffe, Wiclef, Wycliff, Wycliffe, called Doctor evangelicus (* no later than 1330 in Hipswell , Yorkshire ; † December 31, 1384 in Lutterworth , Leicestershire), was an English philosopher , theologian and church reformer.

Live and act

In May 1361 Wyclif was rector of the benefice Fillingham ( Lincolnshire ), which belonged to Balliol. These and other benefices enabled Wyclif to finance his studies; In 1363 he was admitted to study theology. He served as a board member of Balliol College in Oxford and was 1365/67 head of the new college Canterbury-Hall. After his dismissal, there was an internal break with the Church, and Wyclif turned to politics in London. While as a doctor of theology he had the right to hold theological lectures, he was at the same time pastor in positions given by secular princes, an office that he held until his death. The parish of Fillingham was followed by Ludgershall ( Buckinghamshire ) in 1368–1374 and finally the wealthy parish in Lutterworth ( Leicestershire ) in 1374–1384 , which he received as thanks for his services to the crown from the later English regent John of Ghent .

Wycliffe proclaimed the doctrine of “power only through grace”, according to which God himself gives every authority directly, denied the pope's claim to political power and propagated an early “king of God grace”. In his works from 1372 to 1380 ( On the Church , On Civil Rule and On The Office of the King ) he represented the complete subordination of the church to the state. He supported the secular rulers' will to power ( investiture controversy ) in several lawsuits against the Pope and demanded a life in early Christian modesty for church workers, although he himself lived well on his rich benefice until his death.

In 1373 King Edward III sent him . with other clergy to Bruges to bring complaints against the papal see to the papal nuncio , in particular the curia was accused of selling church offices . The "complaints" served to be able to further suspend the contractually agreed annual payments to Rome that had been outstanding for 33 years. Wyclif's concern got through in 1375. As the official prosecutor on behalf of the king, Wyclif gave himself the title "Pecularius regis clericus" (Royal Chaplain).

His juridical, theological and political influence on the compilation of royal complaints against the Pope, which the Good Parliament presented in 1376 , was great. A trial against the Pope, which Wyclif had lost alone in 1370, was crowned in 1373-1375 by the one over the outstanding payments in which he prevailed, and in 1377 culminated in a trial that the Pope led against sentences from Wyclif's works, the thanks to the great reputation that Wycliffe enjoyed at the university and among the people, fizzled in 1378. Encouraged by this, Wycliffe turned now openly against the political influence of the clergy in general and fought against papal "antichristism".

In his main work, the Trialogus, Wyclif taught pantheistic realism, determinism and double predestination ( determinatio gemina ). He taught: “Everything is God; every being is everywhere, since every being is God. ”and“ Everything that happens happens with absolute necessity, evil also happens with necessity, and God's freedom consists in wanting what is necessary. ”He consequently disapproved of images, The veneration of saints, relics and the celibacy of priests , rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation and auricular confession due to his realism . Reddish-clad travel preachers trained by him (called “poor priests”) spread principles among the people that are reminiscent of Protestant teachings 150 years later. His teachings found approval in large parts of the population and significantly influenced the uprising of the English peasants of 1381.

Mendicants , together with the hierarchy set in 1381, meanwhile, the rejection of his teaching by the University and in 1382 in London , meeting Synod by. His writings were condemned as heretical by the Oxford Synod and he lost his offices at court over church affairs. However, for fear of a popular uprising, Wyclif was not officially charged. He calmly continued his pastoral office and in 1383 completed an earlier collection of early English translations of the Bible from the Vulgate into the national language. This translation of the Bible is not the first translation into English , but represents a compilation and revision of earlier translations, as Thomas More noted in 1530 and Francis Aidan Gasquet OSB proved in 1897.

Wycliffe died in 1384 of complications from a stroke during Mass in Lutterworth (now Harborough district, Leicestershire).

The later adherents of Wyclif's ideas, the Lollards , were only sharply persecuted by the English state after an unsuccessful revolt from 1400 onwards. In 1401, William Sawtrey became their first martyr. However, the sometimes brutal inquisition of European heretics, such as the Cathars or Waldensians , cannot be compared with the English persecution. This was characterized by their relative mildness and consideration for the lollards that lived underground, so that the Wyclifian views were preserved in many families until the Reformation .

In 1412, at the end of the English king's persecution, 267 sentences were condemned as heretical by Wycliffe in London . Three years later the Council of Constance ordered all of Wyclif's writings to be cremated and, 30 years after his death on May 4, 1415, declared him a heretic , condemned another 45 sentences from him and ordered his bones to be excavated and cremated, which was thirteen years later, in 1428, actually happened by Bishop Richard Fleming of Lincoln .

reception

In honor of John Wyclif, a non-commercial evangelical organization that campaigns for the worldwide dissemination of the Bible by working out Bible translations, especially for language groups that have not yet been fixed in writing, named itself Wycliff in 1942 .

Wyclif's Life was made into a film by Tony Tew in 1984 under the title John Wycliffe .

Wiclefstraße in Berlin-Moabit is named after him.

Works (selection)

Single track

- Rudolf Buddensieg (ed.): De Christo et suo adversario antichristo. Gotha 1880.

- Josiah Forshall (Ed.): The holy Bible in the earliest English Versions made by John Wycliff and his followers. University Press, Oxford 1850 (4 volumes).

- Anthony J. Kenny (Ed.): On universals ("Tractatus de universalibus"). Clarendon Press, Oxford 1985, ISBN 0-19-824681-1 .

- Gotthard V. Lechler (ed.): De officio pastorali. Karl Barth, Leipzig 1863.

- Gotthard V. Lechler (Ed.): Trialogus. OUP, Oxford 1869 (Conversation between Truth, Lies and Theology).

- Johann Loserth (Ed.): Tractatus de ecclesia. London 1886.

- De otio et mendacitate (against the mendicant monks).

Collections

- Thomas Arnold (Ed.): Select English works of Wycliff. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1869–71 (3 volumes).

- Rudolf Buddensieg (ed.): John Wiclef's Latin pamphlets. Karl Barth, Leipzig 1883.

- Pamela Gradon, Anne Hudson (Eds.): English Wycliffite Sermons. OUP, Oxford 1988 ff.

- 1990, ISBN 0-19-812704-9

- 1988, ISBN 0-19-812773-1

- 1990, ISBN 0-19-812774-X

- 1996, ISBN 0-19-812775-8

- 1996, ISBN 0-19-813005-8

- Johann Loserth (Ed.): Sermones. Johnson Reprint, New York 1966 (4 vols., Reprint of the London edition 1887/90).

- Frederic D. Matthew (Ed.): The English works of John Wycliff. Hitherto unprinted. Kraus Books, Millwood, NY 1990 (repr. Of London 1902 edition).

Remembrance day

On December 31st the Evangelical Church in Germany and the Anglican Community commemorate John Wyclif.

literature

German introductions

- Rudolf Buddensieg: Johann Wyclif and his time. Niemeyer, Halle 1885.

- Ulrich Köpf (ed.): Theologians of the Middle Ages. An introduction. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-534-14815-0 (article on Wyclif).

- Gotthard V. Lechler : Johann von Wiclif and the prehistory of the Reformation. Fleischer, Leipzig 1873 (2 volumes).

- Johann Loserth: Huss and Wicliff. On the genesis of the Hussite doctrine. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1925.

- Werner Raupp : John Wyclif - "Morning Star" of the Reformation, in: Werner Raupp: Werkbuch Kirchengeschichte. 52 people from two millennia [with quiz], Giessen / Basel 1987, pp. 191–197 (short biography) u. Pp. 42–43 (profile).

- Manfred Vasold: Spring in the Middle Ages. John Wyclif and his century. List, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-471-79010-1 .

- Victor Vattier: John Wiclif. Sa vie, ses œuvres, sa doctrine. Leroux, Paris 1886.

- Klaus-Gunther Wesseling: Wyclif, John. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 14, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-073-5 , Sp. 242-258.

Literature on individual topics

- Ludwig Borinski: Wyclif, Erasmus and Luther. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1988, ISBN 3-525-86234-2 .

- Curtis V. Bostick: The Antichrist and the Lollards. Apocalypticism in late medieval and reformation England (Studies in medieval and reformation thought; Vol. 70). Brill, Leiden 1998, ISBN 90-04-11088-7 .

- Mariateresa Fumagalli Beonio Broccieri u. a. (Ed.): John Wyclif. Logica, politica, theologia. Atti del convegno internazionale, Milano, 12-13 February 1999 (Millennio medievale; vol. 37). SISMEL edizioni del Galluzzo, Tavarnuzze (Firenze) 2003, ISBN 88-8450-034-6 .

- William R. Cooper (Ed.): The Wycliffe New Testament 1388. An Edition in Modern Spelling, with an introduction, the original prologues and the Epistle to the Laodiceans. British Library, London 2002, ISBN 0-7123-4728-3 .

- Stefan Diemer: John Wycliffe and his role in the development of modern English spelling and vocabulary (Sprachwelten; Vol. 12). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-631-33741-8 .

- William Farr: John Wyclif as a legal reformer. Brill, Leiden 1974

- Francis Aidan Gasquet: The old English Bible and other Essays, London 1897.

- Kantik Ghosh: The Wycliffite heresy. Authority and the interpretation of texts (Cambridge studies in medieval literature; vol. 45). CUP, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-80720-4 .

- Anne Hudson, Michael Wilks (Eds.): From Ockham to Wyclif (Studies in Church History; Vol. 5). Blackwell, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-631-15055-2 .

- Anthony J. Kenny (Ed.): Wyclif in his times. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1986, ISBN 0-19-820088-9 .

- Stephen E. Lahey: Philosophy and politics in the thought of John Wyclif (Cambridge studies in medieval life and thought / 4; Vol. 54). CUP, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-63346-X .

- Ian C. Levy: A companion to John Wyclif, last medieval theologian. Brill, Leiden 2006, ISBN 90-04-15007-2 .

- Ian C. Levy: John Wyclif. Scriptural logic, real presence, and the parameters of orthodoxy (Marquette studies in theology; Vol. 36). Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, Wis. 2003, ISBN 0-87462-688-9 .

- John D. Long: The Bible in English. John Wycliffe and William Tyndale. University Press of America, Lanham, Md. 1998, ISBN 0-7618-1116-8 .

- Richard Rex: The Lollards. Palgrave, Basingstoke 2002, ISBN 0-333-59751-6 .

- Walter Waddington Shirley: Fasciculi zizaniorum Magistri Johannis Wycliff cum Tritico, London 1858.

- Michael Wilks, Anne Hudson: Wyclif. Political ideas and practice. Oxbow Books, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-84217-009-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about John Wyclif in the catalog of the German National Library

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company, New York 1913.

- Glaubensstimme.de Some texts by Wyclif

- The Latin Works of John Wyclif , e-texts, Center for Medieval Studies, Fordham University

Individual evidence

- ^ Walter Waddington Shirley: Fasciculi zizaniorum Magistri Johannis Wycliff cum Tritico, London 1858, p. XLVI.

- ^ Francis Aidan Gasquet: The old English Bible and other Essays, London 1897, p. 137.

- ↑ John Wyclif in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wyclif, John |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wicliffe, John; Wiclef, John; Wycliff, John; Doctor evangelicus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English philosopher, theologian and church reformer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 1330 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hipswell , Yorkshire |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 31, 1384 |

| Place of death | Lutterworth , Leicestershire |