Irish War of Independence

| date | January 1919 to July 1921 |

|---|---|

| place | Ireland |

| Exit | Anglo-Irish Treaty , partition of Ireland |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| losses | |

|

550 dead |

714 dead |

The Irish War of Independence ( English Irish War of Independence , Irish Cogadh na Saoirse , "War of Liberation") lasted from January 1919 to July 1921. It was organized by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in a kind of guerrilla -Kampf against the British government in Ireland out . The IRA, which fought in this conflict, is often called "Old IRA" ( Old IRA ) in order to stand out from the later groups (in other dispositions) that used the same name.

Origin and name

The Irish War of Independence is also known as the “Irish Revolution ” to draw attention to the social and political dimension alongside the military events. Because beyond the national movement there was a strong participation of the labor movement , also apart from the urban centers, which are in the foreground in most of the stories. The agricultural workers' movement in particular, with its mass mobilizations, played a major role in the struggle for independence. According to the historian Terence M. Dunne, “the labor movement - especially the agricultural labor movement - was at the center of the revolution”, even if it is “only a minor aspect” in the current memory of the events of that time.

Different dates are given for the beginning of the War of Independence. Some Irish Republicans date it to the proclamation of the Republic of Ireland during the Easter Rising in 1916. In this view, the 1919-1921 conflict (and the Irish Civil War that followed ) was only waged to defend that republic against attempts to destroy it. More widespread is the dating of 1919, i.e. the unilateral establishment of an independent Irish Parliament (generally: Dáil Éireann ; in this case: First Dáil ), which was made up of the majority of the 1918 national Irish elections (as part of the United Kingdom elections ) elected parliamentarians.

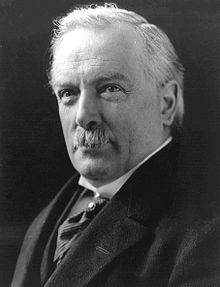

The Irish nationalism had in the late phase of the First World War put a new boost when Prime Minister David Lloyd George , the conscription was extended to the Irish. This plan met with such strong rejection that he abandoned what was widely viewed in Ireland as a triumph and proof that the hated government in London could be forced to give in. Many young men who feared being called up soon joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood . In response to their militant protests, the British government arrested the leading nationalists Arthur Griffith and Éamon de Valera , whereupon Michael Collins, who had remained free, began to build a powerful resistance movement: the Óglaigh na hÉireann , the "Irish Republican Army" (IRA). On January 21, 1919 a group of IRA volunteers killed under Dan Breen two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (next to the Dublin Metropolitan Police , the second police force in Ireland), as they refused to them in Soloheadbeg ( County Tipperary ) guarded explosives to hand over. This event is widely seen as the beginning of the War of Independence, although the men in the raid acted independently and not on official orders from the IRA. South Tipperary was placed under martial law three days later .

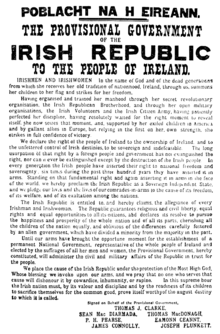

On the day of the shooting, the First Dáil gathered at the Mansion House in Dublin . This parliament and its ministries proclaimed the independence of Ireland under the cabinet at the time ( Aireacht ). It referred to the Easter proclamation that Patrick Pearse had read out in 1916 at the beginning of the Easter Rising. The IRA, as the "Army of the Irish Republic" received a mandate from the Dáil to wage war against Dublin Castle , at that time the seat of the British administration and the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland . The Dáil called for the withdrawal of the British military garrisons and called on the "free nations of the world" to recognize Ireland's independence. The only government that followed this call was the Bolshevik government of Soviet Russia , which at the time was not recognized internationally.

The violence is spreading

Volunteers began raiding British government properties for weapons and money, and murdering prominent members of the British administration. The first victim was Judge John Milling, who was shot dead in Westport , Co. Mayo for sentencing volunteers to prison terms for unlawful gathering. They successfully used the tactic of quick raids without uniforms and terrorist attacks. Although some Republican leaders, above all Éamon de Valera , preferred conventional warfare in view of the recognition of the new republic by the community of nations, they could not prevail against the more experienced Michael Collins and the broad leadership of the IRA, which conventional tactics for blamed the military defeat at the Easter Rising. Initially, the violence exercised did not lead to any great support among the Irish population. This changed when the British forces also acted very brutally and ruthlessly. This included property destruction, arbitrary arrests, and unprovoked shootings. The violence started slowly, but by 1920 it was the norm.

Irish nationalist and politician Arthur Griffith , who was actively involved at the time, said British troops carried out over 38,000 attacks on private homes, arrested 4,982 suspects, committed 1,604 armed attacks, burned 102 locations and killed 77 unarmed Republicans or civilians in the first 18 months of the conflict. Griffith was responsible for establishing the courts of the Dáil courts , a judicial system parallel to the British courts. The Dáil Courts would replace them as soon as the moral support and territorial control of the IRA grew.

The main target of the IRA during the conflict was the predominantly Catholic police force of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), considered to be the eyes and ears of the British government in Ireland. Its approximately 9,700 members and 1,500 posts, especially the outlying ones, were vulnerable and a welcome source of the weapons they needed. The RIC's policy of exclusion was supported by the Dáil and has proven to be successful. The longer the war lasted, the more the RIC became demoralized and the more people turned away from it. The number of RIC leaving rose dramatically, and recruiting fell sharply. Often they even had to buy food at gunpoint, as some shops didn't want to sell them any more. Some RIC people also secretly cooperated with the IRA, either out of fear or sympathy, and provided them with valuable information. 165 members of the Royal Irish Constabulary were killed and 251 wounded during the war.

Michael Collins and the IRA

Michael Collins was the driving force behind the independence movement. Actually finance minister of the government, he was actively involved in the provision of funds and weapons to IRA units as well as in the selection of officers. His intelligence , organizational skills and the urge to move forward inspired many who came into contact with him. He created an effective network of spies within sympathizers in the G division of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and other major branches of the British government. The G division was loathed by the IRA because it was often used to uncover spies unknown to the British soldiers - or later the Black and Tans . Collins founded the Squad , a special unit that was only used to uncover and kill G-men . Many of these G-men were given a chance to leave or leave Ireland by the IRA, and some took advantage of it.

Although the IRA had more than 100,000 members on paper by converting the Irish Volunteers , its leader Michael Collins estimated the number of active members at just 15,000. There were also supporting organizations for the IRA - the women's group Cumann na mBan and the children's movement Fianna Éireann , which delivered weapons and information as well as provided food and accommodation.

The IRA was supported by the widespread assistance of much of the Irish population, who refused to provide information to the Royal Irish Constabulary or the British military, and who often provided "safe shelter" and provisions for passing IRA units. Much of the IRA's popularity was due to the ruthless behavior of British forces. Regarding the government's (unofficial) policy. The reprisals began in September 1919 in Fermoy ( County Cork ), where 200 British soldiers looted the main shops of the village and burned after one of them, after refusing his weapons to the local IRA surrender, had been killed. Actions like this were repeated in Limerick and Balbriggan , increasing local IRA support as well as international support for Irish independence.

In April, after various raids by the IRA, tax revenues collapsed completely. People were encouraged to support Collins' National Loan and raise funds for the “new” government and its army.

The British reaction - "Black and Tans" and "Auxiliaries"

The Black and Tans were created to aid the weakened Royal Irish Constabulary . 7,000 strong, they consisted primarily of former British soldiers who had already fought in the First World War. Most of them came from English and Scottish cities. Officially, the Black and Tans were part of the RIC, but in reality they were a paramilitary organization with a reputation for murderers, terrorists, drunkards and great indiscipline that harmed the British government in Ireland more than any other group. After the Black and Tans came the group of auxiliaries (literally translated: "auxiliary force"), which consisted of up to 1900 former British army officers. In terms of violence, reputation, and horror, this group easily rivaled the Black and Tans. The auxiliaries, however, were even more effective and tried harder to take on the IRA.

Outside Dublin, Cork was the city of the most intense fighting. Many of the "tactics" that were soon to be used across Ireland came from Cork; B. demolishing homes or killing prominent Republicans in revenge for IRA attacks. In March 1920, the mayor of Cork and Sinn Féin member Tomás MacCurtain was shot dead by men with black faces in front of his wife. These men were later seen returning to the local police barracks. His successor, Terence MacSwiney, died on a hunger strike in Brixton Prison in London .

In November 1920, Collins "Squad" executed 19 British agents (known as the "Cairo Gang") who were tasked with killing Collins and other key leaders. On the same day, the auxiliaries in turn drove armored vehicles into Croke Park , Dublin's main stadium, and fired indiscriminately into the crowd. 14 unarmed people were killed and 65 wounded. Later that day, three Republican prisoners were shot dead while allegedly trying to escape. This day went down in history as Bloody Sunday . Today the Hogan Stand (Hogan Grandstand) in Croke Park commemorates the player Michael Hogan from Tipperary , who was killed that day.

In Cork, the IRA used the flying columns for the first time : mobile units consisting of around 100 men who struck in devastating ambushes and then withdrew into the surrounding landscape, which they knew far better than the British soldiers. Some regiments of the British Army had a reputation for killing unarmed prisoners. The Essex Regiment was one of them. In November 1920, just a week after Bloody Sunday in Dublin, the IRA's West Cork unit under Tom Barry ambushed an auxiliaries patrol at Kilmichael and killed all 18 soldiers. It is believed that some soldiers were shot after they surrendered. This raid resulted in the entire province of Munster being placed under martial law.

The following eight months up to the armistice in July 1921 saw a spiral of violence: 1,000 deaths (300 police officers / soldiers and 700 civilians or IRA volunteers) between January and July 1921. In addition, 4,500 IRA members (or suspects Sympathizers) arrested. In May 1921 IRA units captured the Custom House (seat of government) in Dublin and burned it down. This was a symbolic attempt to show that British rule in Ireland was unsustainable. From a military point of view, it was a fiasco: five IRA members were killed and eight arrested. This again showed that the IRA was not trained and equipped enough to take on British units conventionally. By July 1921, most IRA units were in dire straits of weapons and ammunition. Despite its effectiveness in guerrilla warfare, the IRA, as militant IRA officer Ernie O'Malley later recalled, "was never able to evict the British from anything larger than a medium-sized police station." On the eve of the armistice, many Republican leaders, including Michael Collins, believed that if the war continued, the existing IRA could be dismantled. Therefore, plans were made to "bring the war to England". It was decided that key points of the economy such as B. bombing the Liverpool docks. The units that were to be entrusted with these missions would find it easier to escape captivity as Britain was not under martial law and the public was unlikely to accept it. The armistice prevented these plans from being carried out.

The propaganda war

Another facet of the war was the use of propaganda on both sides. The British tried to portray the IRA as hostile to Protestants in order to gain support for the harsh approach in Great Britain as well as the Irish Protestants. In their publications, the denomination of spies or collaborators killed by the IRA was indicated whenever the victim was a Protestant. In the case of Catholic victims (which was the majority), the denomination was not noted in order to create the impression that the IRA only kills Protestants. They also encouraged newspaper publishers to do the same. In the summer of 1921 a series of articles appeared in a London magazine entitled "Ireland and the New Terror - Living Under Martial Law " (Ireland under the New Terror, Living Under Martial Law) . Claiming an independent report on the situation in Ireland, the article portrays the IRA in a very dubious light. In reality, the author, Ernest Dowdall, was a member of the Auxiliaries, and the series of articles was built in by the Dublin Castle Propaganda Department to influence public opinion, which was slowly emerging directed against the behavior of "their" armed forces in Ireland.

The other side (especially Desmond FitzGerald and Erskine Childers ) published the Irish Bulletin , the “official” newspaper of the Republic of Ireland , for propaganda purposes , with detailed descriptions of atrocities committed by the British government which the Irish and British newspapers were unable or unwilling to print. The (weekly) newspaper was secretly printed and distributed across Ireland to international press agencies and to supporters among American, European and British politicians.

armistice

The war ended with an armistice on July 11, 1921, after the conflict had turned into a kind of "stalemate" situation. From the UK government's point of view, it appeared that the IRA's guerrilla attacks could go on forever, with ever increasing casualties and costs.

More important, however, was the fact that the British government had to accept increasingly serious criticism of the way British troops were operating in Ireland. On the other hand, the leaders of the IRA saw the collapse of the group due to a lack of weapons and money and an ever-increasing supply of soldiers from Great Britain. The final breakthrough to the armistice is thanks to three people: King George V , General Jan Smuts of South Africa and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George . The king, known to be dissatisfied with the actions of the Black and Tans in his government, was not pleased to open the newly created Northern Irish Parliament in the light of the partition of Ireland. Smuts, a close friend of the king, suggested that he take the opportunity to appeal for peace in Ireland. The King asked Smuts to put his ideas on paper and then forwarded a copy to Lloyd George. Lloyd George then invited Smuts to a British Cabinet meeting where Smuts was to comment on the "interesting" proposals Lloyd George had received. Neither informed the ministers that Smuts was the original author of the proposal. With the encouragement of Smuts, the King and the Prime Minister, the Ministers approved, albeit reluctantly, the King's proposed address on reconciliation with Ireland.

The speech did not fail to have an effect. Taking advantage of the moment, Lloyd George suggested that he seek talks with Éamon de Valera in July 1921. The Irish, unsure of the extent of the speech, since it obviously did not correspond to the opinion of the entire government, nevertheless saw in it the goodwill of the King, Smuts and Lloyd Georges. Reluctantly, they agreed to the talks. De Valera and Lloyd George ultimately agreed to a ceasefire that would end the fighting and lay the groundwork for detailed negotiations. These negotiations were postponed for a few months as the British government insisted that the IRA must first surrender its weapons. But this request was ultimately dropped. It was agreed that the British troops would remain in their barracks for the time being.

The peace talks ultimately culminated in the Anglo-Irish Treaty , which was ratified three times : through the Dáil Éireann in December 1921 (through which it gained legitimacy in the Irish system of government), through the Parliament of Southern Ireland in January 1922 (through which it gained constitutional legitimacy the - in British eyes - right government in Ireland) as well as through both houses of the British Parliament .

The treaty allowed Northern Ireland , created in 1920 by the Government of Ireland Act , to leave the Free State of Ireland, which it immediately did. As noted, a "boundary commission" (was Boundary Commission ) is used, which should decide on the exact course of the border between the Free State and Northern Ireland.

A new system of government was also introduced for the newly created Irish Free State , although in the first year two governments existed side by side: a cabinet ( Aireacht ) under the leadership of President Arthur Griffith had to answer to the Dáil Éireann (House of Commons) and a provisional government, which opposed each other the "House of Commons in Southern Ireland" had to answer.

The Irish civil war developed out of the internal dispute over the acceptance of this Anglo-Irish treaty .

See also

literature

- Tim Pat Coogan: Michael Collins. Random House, New York. ISBN 978-1-78475-326-9 .

- Francis Costello: The Irish Revolution and its Aftermath 1916–1923: Years of Revolt. Irish Academic Press, 2003, ISBN 0-7165-2633-6 .

- T. Ryle Dwyer: Michael Collins. Biography. Unrast, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-928300-62-8 .

- Ronan Fanning: Independent Ireland (Helicon History of Ireland), Dublin 1983, ISBN 0-86167-301-8 .

- Diarmaid Ferriter: A Nation and not a Rabble: The Irish Revolution 1913-23. Profile Books, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-78125-041-9 .

- Francis Stewart Leland Lyons: Ireland Since the Famine. Fontana, London 1973, ISBN 0-00-686005-2 .

- Dorothy MacCardle: The Irish Republic. Wolfhound Press, 1999, ISBN 0-86327-712-8 .

- Joseph McKenna: Guerrilla warfare in the Irish War of Independence, 1919–1921. Jefferson, NC 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-5947-6 .

- John A. Murphy: Ireland in the Twentieth Century (The Gill History of Ireland, Volume 11), Dublin 1975, ISBN 0-7171-1694-8 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Terence M. Dunne: The Peasant Movement During the Irish Revolution. The case of County Kildare , in: Work - Movement - History , Volume III / 2017, pp. 55–73.

- ^ William R. Polk : Uprising. Resistance to foreign rule: from the American War of Independence to Iraq . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2009, p. 94 f.

- ^ Francis Stewart Leland Lyons: Ireland since the famine . Fontana Press, London, 10th ed. 1987, ISBN 0-00-686005-2 , pp. 408-409.