History of Dublin

The history of Dublin goes as early as 2000 years ago, and for most of the recent period was Dublin both the "capital" of Ireland as well as the center of culture, education and industry. The city had experienced very different times over the years. The history of Dublin is closely linked to the history of Ireland .

Foundation and early history

The earliest reference to a settlement in the Dublin area can be found in the writings of the Greek astronomer and cartographer Claudius Ptolemy in AD 140, who named the place Eblana Civitas . This leads to a history of at least 2000 years for the square, because the settlement (not a city) must have existed for some time before Ptolemy found out about it.

In the 9th century there were two settlements in the area of the present city. From Orkney originating Vikings built here first winter camp before the settlement 841 Dyflin in the area around today's Christ Church Cathedral founded. The name Dyflin refers to the Irish name An Duibhlinn ("Dark Pond"). Further up the river was the older but less important Celtic settlement Áth Cliath (Eng. "Hurdle ford"). The name of the Celtic settlement is today again the city name in the Irish language , which is Baile Átha Cliath , while the English name of the Viking settlement comes from. In 852 the Normans Ivar Ragnarsson (the Boneless ) and Olaf the White landed in Dublin and turned the settlement, which had existed since 841, into a fortress. The Vikings founded the Kingdom of Dublin . The year 988, when the "King of Meath" Máel Sechnaill II briefly recaptured Dublin from the Vikings, is now the official founding year of the city, which in 1988 celebrated its 1000th anniversary. The Vikings had coins minted here from 977 and ruled Dublin for almost three centuries despite their defeat by the Irish high king Brian Boru in the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.

Dublin became the center of English power in Ireland after the Normans conquered the southern parts of Ireland's Munster and Leinster in the 12th century . As a result, the center of political power shifted from that of the Gaelic high kings in Tara (County Meath ) to today's capital. Over time, however, the Anglo-Norman conquerors became more and more integrated into Irish culture, leaving only a small area outside of Dublin known as " The Pale " under direct English control. People outside this area were considered uncivilized, which led to the well-known English expression “Beyond the Pale” (meaning “completely unacceptable”).

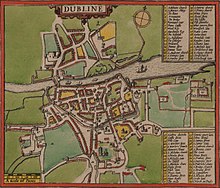

Medieval Dublin

After the Normans had conquered Dublin in 1171 and established a feudal system there, many of the originally Scandinavian inhabitants left the old part of the city south of the River Liffey and settled north of it; this settlement is known as "East Mantown" or "Oxmantown". Dublin became the capital of the English occupiers in 1171 under Henry II ("Lordship of Ireland" 1171–1541) and was almost overrun by English and Welsh settlers. Many settlers from the neighboring island also settled in the rural area around Dublin (in the north as far as Drogheda ). In Dublin itself, English power was concentrated around the newly built Dublin Castle . The city continued to be the seat of the Irish Parliament , which was made up of envoys from the English communities. Important buildings from this period include St. Patrick's Cathedral , Christ Church Cathedral and St. Audoen's Church , all of which are within a 1 km radius of each other.

Over time, the inhabitants of the "Pale" developed their own identity, similar to that of other colonies that were spatially enclosed by "barbaric natives". The siege mentality of the Dubliners in the Middle Ages is best seen in the annual march to "Cullen's field" in Ranelagh where in 1209 500 Bristol settlers were massacred by the O'Toole clan during a festival. Every year on “Black Monday”, settlers from Dublin marched to the site of the atrocity and hoisted a black flag in the direction of the Wicklow Mountains ; a gesture of challenge against the native Irish. This march was so dangerous until the 17th century that the participants had to be protected from the "enemy from the mountains" by police officers from the city.

Medieval Dublin was a narrowly enclosed area south of the Liffey of about 3 km² with 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants. Beyond the city walls were the outskirts, such as B. the "Liberties" in the area of the Archbishop of Dublin or " Irishtown ", where the Gaelic population lived after they were expelled from the city area by a 15th century law. Although the original Irish inhabitants were not supposed to live in the city or in the surrounding areas, many did, and so it was that in the 16th century the Irish language became more and more established alongside English.

Life in Dublin in the Middle Ages was dangerous. In 1348 the city was ravaged by the deadly bubonic plague ("Black Death") that raged across Europe in the 14th century . Victims of the disease were buried in mass graves - in an area that is still known today as the "Blackpitts" ("black pits"). The disease broke out again and again at regular intervals until its peak in 1649.

In addition to the disease, the city was also the scene of recurring violence among the inhabitants as well as in great military battles. Protection money ("black rent") was even paid to the neighboring Irish clans in order to avoid their predatory attacks. In 1314 an invading Scottish army burned the outskirts of the city. After the English interest in their Irish colony waned, the defense of the city against the surrounding Irish passed to the Fitzgerald's (Earls of Kildare), who dominated Irish politics until the 16th century. But there were also quarrels within the ruling house. In 1487, during the English War of the Roses , the Fitzgeralds occupied the city with the help of French troops and crowned Lambert Simnel , who came from York , as King of England . 1536 besieged the same dynasty under Silken Thomas due to the capture of Gerald FitzGerald, the 9th Earl of Kildare , the Dublin Castle . Henry VIII then sent a large army to defeat the Fitzgeralds and replace them with English administrators. This was the beginning of the, not always friendly, close relationship between Dublin and the English crown.

Colonial Dublin

Dublin and its people changed with the upheavals in Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries. These saw the first complete conquest of the island under the Tudors . While the old English community of Dublin and "The Pale" were happy about the conquest and disarmament of the Irish people, they were also unsettled by the Protestant Reformation in England; they were almost all Roman Catholic . In addition, they feared compulsory charges for the English garrison through a special parliamentary tax called "cess".

Quite a few Dubliners were executed for participating in the Desmond Rebellions in the 1560s to 1580s. Dissatisfaction in the city intensified during the Nine Years War in the 1590s when Dublin residents were ordered to house English soldiers by decree . Because the wounded remained lying in the streets for lack of proper hospital, diseases spread faster. In 1597, the gunpowder store on Winetavern Street exploded . Almost 200 Dubliners were killed. In 1592 Elizabeth I founded Trinity College , which at that time was still east of the city, as a Protestant university for the Irish nobility . However, the main Irish families spurned the university and instead sent their sons to Catholic universities in Europe.

As a result of all this tension, English rule found Dublin unreliable and encouraged English Protestants to relocate there. These "New English" formed the basis of the English government in Ireland until the 19th century. Protestants became the majority in Dublin in the 1640s when thousands of them fled the 1641 Irish Rebellion . When the city was threatened more and more by Catholic Irish forces, the Catholic Irish were driven out of the city by the English garrison. In the 1640s the city was besieged twice during the Irish Confederation Wars: 1646 and 1649. However, both times the besiegers were driven out before the siege took effect. At the second siege in 1649, a group of Irish Confederates and English royalists , led by an English government garrison, was led into the Battle of Rathmines , which took place on the southern outskirts of the city. After Cromwell's conquest of Ireland in the 1650s, Catholics were banned from living within the city limits, but this law was never strictly enforced. Ironically, this religious discrimination caused the old English community to lose its roots in their homeland and see themselves as part of the Irish "indigenous people". At the end of the 17th century, Dublin was the capital of the Kingdom of Ireland - ruled by the Protestant new English minority. Dublin has never been bigger, more peaceful and more prosperous than at this time in its history.

The Georgian Dublin

In the early 18th century, the English had strengthened their position of power and strict criminal laws, the Penal Laws introduced, which turned mainly against the Catholic majority of the Irish. In any case, Protestant supremacy flourished in Dublin, and the city had been growing rapidly since the 17th century. By 1700 the population exceeded 60,000 and made Dublin the second largest city in the British Empire after London . During the English Restoration , James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde (later "Lord Deputy of Ireland") took the first steps to modernize the city by ordering that the houses along the River Liffey face it. Furthermore, these houses got a new, higher quality facade. This was in contrast to earlier times when the city's citizens ignored the river and even used it as a garbage dump.

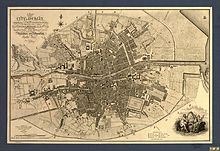

Dublin started in the 18th century as a medieval city in terms of street layout. During the 18th century, Dublin underwent many changes under the Wide Streets Commission , in the course of which the Grand Canal and many of its bridges were built in 1765 . Furthermore, many of the narrow medieval streets were demolished and replaced with wide Georgian streets. Among the new streets were z. B. Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street ), "Dame Street", "Westmoreland Street" and "D'Olier Street". During this time five large Georgian squares were laid out: On the south side "Rutland Square" (today: Parnell Square ) and "Mountjoy Square" as well as "Merrion Square", "Fitzwilliam Square" and St. Stephen's Green on the south side of the Liffey. Although originally the wealthy nobility in the northern part of the city, z. B. in "Henrietta Street" or "Rutland Square" lived, the Earl of Kildare (later Duke of Leinster ) built his town house ("Kildare House"; later Leinster House ) south of the river. This led to a flood of new buildings by the nobility on the south side around the three large squares. The huge houses in the northern part became simple rental apartments, into which many poor people moved. They were often exploited by the owners who put entire families in a large Georgian room. Only the old Dublin district of Temple Bar between "Dame Street" and the Liffey and the area around Grafton Street survived to this day with its narrow, medieval-looking streets.

Although Dublin had a lot to offer culturally - e.g. For example, George Frideric Handel's “ Messiah ” premiered in Fishamble Street in Temple Bar - in the 18th century the city was anything but a “piece of jewelry”. The city's slums (mainly in the north and south-west districts) grew rapidly due to the rural exodus. Rival gangs such as the "Liberty Boys" (weavers from the "Liberties" district) and the "Ormonde Boys" (butcher from Ormonde Quai on the north side) fought bloody battles, often with strong armament and many dead. After unpleasant laws were passed, there were also regular violent demonstrations in front of the Oireachtas . Due to the immigration from rural areas, the demographic balance changed again , and Irish Catholics regained a majority in the city at the end of the 18th century.

Rebellion, Union and Catholic Emancipation

In the late 18th century, Irish Protestants (the English settlers who originally immigrated) saw Ireland as their home country, and Parliament had also successfully advocated greater autonomy and better trade deals. Even so, some radical Irish, influenced by the American and French Revolutions, went a step further and founded the United Irishmen to create a non-denominational democratic republic. The group, led by Wolfe Tone , included Napper Tandy, Oliver Bond and Edward Fitzgerald. The United Irishmen planned to take over Dublin in a rebellion in 1798. The British authorities, on the other hand, had infiltrated the United Irishmen with informants and were well informed of what was happening. Before the Irish Rebellion of 1798 broke out, they arrested the leading figures and stripped the rebellion of coordination. The rebels no longer wanted to wait for the long-promised French help and struck off.

There was sporadic fighting in the outskirts (e.g. in Rathfarnham ), but all in all the situation remained largely under control during the Irish Rebellion . Nonetheless, both Protestant rule and the British government were shocked by what had happened. In response, the Act of Union was passed in 1800, which aimed to incorporate the Kingdom of Ireland into the British Empire . In 1801 the Irish Parliament agreed to its dissolution and Dublin lost great political influence. Although the city continued to grow, it suffered financially mainly from the loss of parliament and the associated loss of income from the high nobility and parliamentarians present. Within a few years, many of the city's finest houses such as Leinster House, Powerscourt House or Aldborough House, once inhabited by the nobility for many years, were for sale. Many of the elegant Georgian districts degenerated into slums. In 1803 Robert Emmet , brother of one of the leaders of the United Irishmen, started another rebellion in the city. However, this was quickly put down and Emmet was hanged.

On April 13, 1829, the Catholic Emancipation Bill came into effect. It brought a significant improvement in the rights of the Catholic population. They owed this mainly to the persistence of Daniel O'Connell , who held mass events on the subject in Dublin, among other places. O'Connell is fighting, albeit unsuccessfully, for legislative autonomy in Ireland. After the introduction of civil rights and participation in British politics, Irish nationalists (mostly Catholics) took control of Dublin's city council in the late 19th century.

Monto

- Main article: Monto

Dublin continued to grow steadily in the 19th century, although the city had lost much of its political importance and wealth. By 1900 the city had over 400,000 inhabitants. Although it was often referred to as the "Second City of the (British) Empire", the large number of dreary tenement houses achieved notoriety, which was also picked up by writers such as James Joyce . The area called “Monto” (around Montgomery Street) became the largest red light district in the Empire, benefiting from many barracks of the British Army, e. B. the "Royal Barracks" (later "Collins Barracks"), which are now part of the Irish National Museum . Monto was "closed" in the mid-1920s after a campaign by the Roman Catholic Legion of Mary against prostitution . A large part of the clientele was also lost when the majority of soldiers left the city in December 1921 through the Anglo-Irish Treaty and on December 6, 1922 through the establishment of the Irish Free State .

The general strike

- Main article: Dublin Lockout

In 1913, Dublin experienced one of the largest and most bitter strikes to ever take place in Ireland and Great Britain , also known as the Dublin Lockout . The strike was called by the militant trade unionist James Larkin , who represented the underpaid Dublin workers. Larkin founded the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) and tried to achieve higher salaries and better working conditions through strikes. In return, William Martin Murphy , owner of the Dublin Tram Company, organized a union of employers with the result of firing all ITGWU members and thus preventing other workers from contributing. Larkin then called on all rail workers to go on strike, which led to the dismissal and lockout ("The Lockout") of all workers who were not ready to leave the ITGWU. Within a month, 25,000 workers were either on strike or laid off. Demonstrations during this period were also overshadowed by rioting with the Dublin Metropolitan Police , in which 3 people died and hundreds were injured. James Connolly then founded the Irish Citizen Army to protect striking workers from the police. The “lockout” lasted 6 months. After that, most of the workers whose families were starving left the Union and returned to work.

The end of British rule

In 1914 Ireland seemed on the verge of independence, but the First World War prevented this. But in 1916 a small group of Republicans led by Padraig Pearse in Dublin organized what would go down in history as the Easter Rising . Although the uprising was suppressed relatively quickly by the British government and although the majority of the Irish were originally hostile to the group, public opinion gradually but definitely changed. The majority now stood behind the leaders who were later executed by the British military. In December 1918 the group that emerged from the rebels won an overwhelming majority of 80% in the general election. But instead of filling the won seats in the British House of Commons , they gathered in the mayor's house and proclaimed the Dáil Éireann (also "First Dáil"), the first Irish parliament since 1801.

The Irish War of Independence that followed between 1919 and 1921 resulted in an armistice and a negotiated peace known as the Anglo-Irish Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland. This created an independent Irish Free State , which only consisted of 26 of 32 counties. This led to the outbreak of the Irish Civil War from 1922 to 1923, when the uncompromising Republicans among the nationalists took up arms against those who agreed to the compromise with Great Britain. The new government of the Free State finally suppressed the uprising in late 1923.

Dublin city center suffered a lot from 1916 to 1922. In addition to 1916, the city was the scene of fierce street fighting when the civil war broke out in 1922. In between, the local IRA groups in town waged a guerrilla war against the police and the British Army . Some of Dublin's finest buildings were destroyed during this period: the historic Post Office (GPO) was totally bombed out after the Easter Rising, James Gandon's Custom House was burned down by the IRA during the War of Independence, and Four Courts was occupied by Republicans and Anglo-Irish supporters Contract bombed; In return, the Republicans blew allegedly (guilt not clear), the Irish National Archives (Irish Public Record Office) and so destroyed a thousand-year-old archive. The bloodiest day of the period was undoubtedly Bloody Sunday in 1920 , when the IRA executed 14 British spies and the army then opened fire on football fans in Croke Park .

The new Free State organized itself as best it could. The new leadership was accommodated in the Viceregal Lodge . Parliament was temporarily established in Leinster House but has remained in that house ever since. Over time, the GPO, Custom House and Four Courts were rebuilt.

Demolition of the rental bunker

In the 1932 election, Eamon de Valera , survivor of the 1916 uprising and leader of the defeated opponents of the treaty in the civil war, gained power. With now increased financial resources, major changes began in Dublin. The demolition of the dreary tenement houses and the replacement with fancy buildings for the poor in Dublin began, but it was not until the 1960s that the plans were implemented extensively. New suburbs such as Marino and Crumlin emerged, but the inner-city slums ultimately remained. However, the measure was only partially successful. Although most of the apartment buildings were removed, there was little time to plan the new houses due to the resulting housing shortage. Districts such as Tallaght , Clondalkin or Ballymun had up to 50,000 inhabitants (in the case of Tallaght) within a very short time, with no shops, jobs or links to transport. As a result, the names of these districts became synonymous with crime, drugs and unemployment for the next few decades. It was not until the 1990s that the problems were greatly reduced by the economic upswing of the Celtic Tiger , only to worsen again after the financial crisis of the years after 2009. Tallaght in particular now has a mixed population structure, lots of shopping opportunities, good transport links and leisure opportunities.

Also in Ballymun, Ireland's only high-rise complex built between 1965 and 1969, but has been synonymous with entrenched poverty, poor education, unemployment and drug addiction since the late 1970s, 26 of the 27 high-rise buildings and large blocks and 16,000 have been demolished since 1999 as part of the EU URBAN initiative People resettled in newly built houses. It was the largest urban renewal project in Europe funded in this context. However, social renewal is still a long way off. After the 2009/10 crisis, youth unemployment (around 40%) and dependency on charities remained high, while willingness to learn and the number of full families remained low. The population now has enough space, but no longer has an emotional connection to the square.

Ironically, for all the prosperity it has achieved, Dublin has a shortage of houses. The resulting drastic increases in rents and purchase prices drew many Dubliners from the expensive city to the cheaper surrounding counties such as Meath , Louth , Kildare and Wicklow . This in turn led to longer journeys, major traffic problems in Dublin and urban sprawl around Dublin in general.

The "emergency situation"

The Republic of Ireland was officially strictly neutral during World War II. However, they were very benevolent towards the Allies. For example, flights by Allied aircraft from Northern Ireland over the "Donegal Corridor" were tolerated. British and American airmen who made an emergency landing in Ireland were mostly deported to Great Britain, while Germans were interned. The war was referred to in parlance as "The Emergency" rather than "War". Dublin avoided area bombing because of its Irish neutrality . However, some bombs were dropped over Ireland by the German Air Force . The attack with the most serious consequences occurred on May 31, 1941 in Dublin. 28 people were killed on “North Strand”, a workers' district in the northern inner city area. Immediately afterwards both England and Germany blamed each other; however, after just under two weeks, the German government described the bombing as a mistake and promised to make amends. In Ireland, the attack was seen as an attempt to drag the country into the war or to punish it for dispatching firefighters after the bombing of Belfast . A faction of the IRA hoped to gain advantages from the Germans through the war and planned to invade Northern Ireland . They successfully stole almost all of the Irish Army's ammunition during a raid on the Phoenix Park weapons depot. In return, the de Valera government interned members of the IRA and had some of them executed. As in the rest of Ireland, the war caused food shortages in Dublin.

The destruction of Georgian Dublin

From the 1950s on, Georgian Dublin was caught in the crossfire of the Irish government's development plans. Whole rows of 18th century buildings, especially on Fitzwilliam Street and near St. Stephen's Green , have been demolished to make way for office and government buildings. This development was supported by Ireland's nationalistic stance at the time, which wanted to erase all "memories" of foreign rule by the British. An extreme example of this mindset was the 1966 IRA 's destruction of the statue of Nelson ( Nelson's Pillar ) on O'Connell Street . The statue of the famous British Admiral , a Dublin landmark for a century, was destroyed by a small bomb just before the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising . In 2003 the new Dublin landmark, the 120 meter high Dublin Spire , was completed at this point .

But also entire areas, such as B. Wood Quay , where archaeologically significant finds of the early settlement of Dublin by the Vikings were, fell victim to the destruction of the planners, even if this happened only after a long legal battle between the government and supporters of conservation. A similar case later occurred while planning the M50 ring road around Dublin, which now runs through the ruins of Carrickmines Castle . In the Middle Ages, the castle was part of the southern border of the " Pale ". Furthermore, it became known that many permits for controversial buildings, both in the countryside and in historical areas, were obtained through bribery and nepotism. There are many ongoing proceedings aimed at clearing up the background to these abuses.

Renewal of Dublin

Despite a few exceptions, since the 1980s there has been a little more sensitivity among city planners about the preservation of Dublin's cultural heritage. Most of the Georgian buildings in the city are now listed buildings. The renovation of Temple Bar , Dublin's last surviving medieval quarter, also began at this time. In the late 1980s, Grafton Street and Henry Street became pedestrian streets.

The real transformation of Dublin began in the late 1990s when the economic power of the Celtic Tiger rose sharply. Dublin, until then full of run-down places, suddenly experienced a real hurricane of improvements and building work - especially in the construction of apartments and office buildings. The most spectacular “new building” is certainly, next to the Dublin Spire , the almost one kilometer long financial district (International Financial Services Center - IFSC) on the North Quays.

immigration

Dublin has traditionally been an emigrant city with high unemployment rates, forcing many residents to leave the city and the country. But from the mid-1990s this trend reversed drastically and drew emigrants from all over the world to the Emerald Isle. Dublin is now home to many nationalities including people from China , Nigeria , Russia , Poland , Romania and many other countries.

literature

- Craig, Maurice James: Dublín. 1660-1860. Penguin Books 1992.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Killeen, Richard (2009): Historical Atlas of Dublin. Dublin, p. 12f.

- ^ Killeen, Richard (2009): Historical Atlas of Dublin. Dublin, pp. 87f.

- ↑ http://cordis.europa.eu/news/rcn/6740_de.html EU funding database, 1996.

- ↑ Donegal Corridor . Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Irish neutrality: holy cow or wishful thinking . Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Bombing of Dublin's Short Strand. Retrieved January 17, 2018.