William Martin Murphy

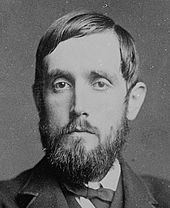

William Martin Murphy (born January 6, 1845 in Derrymihan near Castletownbere , County Cork , † June 26, 1919 in Dublin ) was an Irish entrepreneur who owned numerous railway companies in Ireland, Great Britain and Africa. From 1885 to 1892 he represented Dublin in the British House of Commons as a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party and, with the purchase of the Irish Independent and other newspapers, became the first Irish press magnate to change the Irish press landscape. However, he was best known for his role in the 1913 labor dispute ( Dublin Lockout ), in which he led the employers' side and with the help of lockouts and the resulting social misery broke the resistance of the workers.

Life

Early years

William Martin Murphy was born to contractor Denis Murphy and was the only child. Shortly after he was born, his father relocated his business to Bantry . When William Martin was four years old, his mother Mary Anne Martin passed away. His grandmother, Mary Murphy, who then took care of the upbringing, died five years later. After attending school in Bantry, Murphy moved to Dublin in 1858 to the Jesuit- run Belvedere College and stayed with a friend of his father's, AM Sullivan, who was then working on the Irish national weekly newspaper Nation . After graduating from school, he took up a degree in architecture at the Catholic University in 1863 and also worked for the Dublin architect John J. Lyons. He also wrote for the Nation and the Irish Builder . When his father died unexpectedly in 1863, however, he had to break off his studies and take over his father's company. Only a few years after taking over his father's company, he moved its headquarters to Cork . His marriage to Mary Julia Lombard, daughter of the influential businessman James Fitzgerald Lombard, also contributed to his early business success. In 1875 Murphy was so successful that he was not only able to relocate the headquarters of his company to Dublin, but also had the means to purchase Dartry House, a stately home in the south of Dublin.

Building the tram and railroad empire

During this time, the introduction of horse-drawn trams in the United States and London by George Francis Train aroused Murphy's interest. After approval in 1871, there were three companies operating horse trams in Dublin in 1877. Murphy and his father-in-law ran the youngest of these three companies, the Dublin Central Tramway Company , which, thanks to the capabilities of his construction company, was able to expand very quickly. In 1880 all of these operations were merged to form the United Tramways Company , with James Fitzgerald Lombard as chairman of the board and Murphy as chairman of the board. The company promoted and benefited in particular with the beginning of electrification from 1896 onwards from the expansion of Dublin, which resulted in numerous new suburbs that were connected to the center by trams .

This success opened the opportunity for Murphy to expand the business to railroads. Here he received the contract for the railway line from Drimoleague to Bantry , which was officially opened on July 3, 1881. In the following year he was allowed to represent the Dublin Archbishop Edward McCabe in his capacity as a shareholder in the Cork and Bandon Railway Company . In 1884 the railway line between Clara and Banagher followed . In December 1885 he became a board member of the Waterford and Limerick Railway , and around the same time he came to the board of West Clare Railways . When in 1901 several railway companies were merged to the Great Southern and Western Railway , he was not immediately taken over as a board member; At the end of 1903, however, he succeeded in succeeding a deceased board member.

Since Murphy entered the railroad business when many important lines already existed, his entrepreneurial activities in the field of tram construction were much more significant, which he carried out in addition to Dublin in Cork , Belfast , south London , Isle of Thanet , Hastings , Bournemouth , Paisley and even operated in Buenos Aires . His trams in Dublin were considered unparalleled throughout the UK for efficiency and comfort, both in the system of routes available and in perfect organization.

Political career

When the constituency in Dublin was split up in 1885, Murphy's increasing importance and fame as a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party founded in 1882 gave him the opportunity to move into the lower house as a member of the constituency of St Patrick's . This turned out to be very fortunate for his further business development, as many decisions regarding the development of public transport depended on the House of Commons. Here he quickly succeeded in influencing the related legislation. For example, in 1886 he supported the Public Works Loans Tramways (Ireland) Act , which authorized the Treasury to issue loans with shares as collateral, and through that program took out a £ 54,000 loan himself for a West Clare Railway project , where he was on the board and at the same time benefited from the contracts awarded. He advocated a national government in Ireland and named Belgium as a model in a speech on January 10, 1887 . He argued that self-government would lead to economic prosperity and strongly opposed prejudice against Irish workers, referring to his many years of experience as an employer. During a construction workers' strike in Dublin in 1890, he advocated this in an article published March 24 in the Freeman's Journal , pointing out that workers would only charge four pence an hour - an amount he had been asking ten years earlier paid to his workers.

When in 1890 it became public that Charles Parnell was having an affair with Katharine O'Shea , the wife of his fellow party member, who had had several children, and Parnell refused to resign because of it, the Irish Parliamentary Party split . Murphy joined Justin McCarthy's group backed by Dublin Archbishop William Walsh . Murphy and Walsh knew each other very well, trusted each other, and kept in touch with telegrams throughout this affair. The opponents of Parnell, who had formed as the Patriotic Party , faced the problem that the Freeman's Journal remained under Parnell's control and thus no newspaper of its own was available to influence public opinion. On December 15, 1890, an emergency newspaper appeared under the name Suppressed United Ireland , which called in particular the supporters and members of the Irish Parliamentary Party to join the Patriotic Party . The National Committee was established as an alternative to the Irish National League , the main instrument of the Parnell-led movement, which the Irish Parliamentary Party continued to support . Murphy provided rooms and also took over the management. He told Archbishop Walsh that he had already won around 3,000 prominent supporters and that the mood was very good after the election in Kilkenny .

As a successor to the emergency newspaper, a thin sheet of paper was first published with the name Insuppressible ; a little later, under the direction of Healy and Murphy, it became a somewhat larger newspaper called the National Press . It was very difficult to find enough advertisers and buyers for the paper as Dublin remained largely loyal to Parnell thanks to the still successful Freeman's Journal . This changed gradually, however, because Murphy continuously financed the newspaper, helped the support of the bishops and on March 6, 1891 Thomas Sexton could be won as editor. Since this made the situation for the Freeman's Journal increasingly difficult, it ultimately distanced itself from Parnell, who then tried to found the Irish Daily Independent as a new newspaper, but died unexpectedly early on October 6, 1891.

After Parnell's death, John Dillon and William O'Brien seized the opportunity to take over Freeman's Journal and proposed that the two newspapers be merged. Murphy and Healy were initially against, but could not prevail. With National Press shareholders receiving shares in Freeman's Journal , Murphy and Healy became members of the new board. In a lengthy argument, Dillon and Sixton, also on the board, tried to push both Murphy and Healy out. Archbishop Walsh, who was also a member of the board, was drawn into the dispute on both sides. When Archbishop Walsh announced on February 20, 1893 that he would make his recommendations on how to proceed at the March 6 session, and there were rumors that Archbishop Walsh would support Dillon, both Murphy and Healy each sent letters to the Archbishop announcing them not to regard its recommendations as binding. This was viewed as a breach of trust by Archbishop Walsh, and the previously very good relationship between Murphy and Walsh was never to recover. In the end, Murphy was unable to keep his board seat, which ultimately also meant that he lost his investment in the newspaper.

In 1892 Murphy was unable to defend his seat in the House of Commons. In a by-election in the constituency of South Kerry , Murphy was run as a candidate by the local Irish Parliamentary Party in September 1895 . It is unclear if this was done with Murphy's consent, but Dillon's reaction came promptly with TG Farrell immediately being contested. Despite Healy's support, Murphy lost by only 474 to 1209 votes. As a result, Murphy lost his seat in the Irish National Federation and Healy lost his party offices, although he remained a member. Shortly thereafter, Justin McCarthy gave up the party leadership, so that Dillon was his successor.

The way to the press baron

However, Murphy never lost sight of the goal of controlling a daily newspaper that would be more successful than the Freeman's Journal, which Sixton worked on behalf of Dillon . He became honorary treasurer of the People Rights Association , which was affiliated with the distressed weekly Nation . On Murphy's initiative, the People Rights Association acquired the nation with the aim of developing it into a daily newspaper. Murphy spent most of the necessary capital and was soon the sole owner of the nation Company Ltd . Thus in the last few years of the 19th century there were three nationally oriented newspapers, the Dillon-controlled Freeman's Journal , the pro-Parnell-owned and John Redmond- controlled Irish Daily Independent, and the Murphy-owned Daily Nation . When the Irish Daily Independent ran into financial difficulties and had to be sold, the Freeman's Journal put in an offer to buy. Redmond, who was still on good terms with Healy despite the party split, asked him if the Irish Daily Independent could not be bought by Murphy. Although Murphy was initially reluctant, he was persuaded by Healy and then merged the two newspapers in the Irish Independent Newspapers Ltd , founded in 1901, which then also included the Weekly Independent , the Nation , the Evening Herald and the Saturday Herald . This coup, coupled with Healy's continued attacks in the newspapers against Dillon, led to the following saying:

"Mr Murphy bought the knives, and Mr Healy did the stabbing."

"Mr. Murphy bought the knives and Mr. Healy stabbed. "

Still, despite Murphy's efforts and investments, the newspapers remained a grant business. To change that, Murphy consulted two newspaper experts who recommended the type of tabloid that Northcliffe had introduced to the Daily Mail as a model, as it was extremely successful and this success was also repeated in the Daily Express , which emulated the approach . Murphy then appointed Tim Harrington, also from Castletownbere, as editor-in-chief of the Irish Independent with the aim of adopting these successful concepts and increasing the use of photographs. Also, unlike in the past, the paper was no longer intended to be used for direct political disputes, but to report largely in a distanced and non-partisan manner. Murphy then accompanied Harrington to London to see the new Linotype typesetting machines, which were then purchased in greater numbers. After the lease on the old premises on Dame Street expired, Murphy found a four-story building on Middle Abbey Street that would house the new newspaper. The first edition on January 2, 1905, printed a total of 50,000 copies - a dramatic increase from the Irish Daily Independent's 8,000 circulation .

Although the Daily Mail served as an outward model, the Irish Independent eschewed sensationalism and instead sought good journalism in a clear language that sought objectivity. This in connection with the new style of a newspaper was very well received, although or precisely because everything was clearly different from the older newspapers. Columns signed by name and literary contributions by well-known politicians and authors were also new. In addition to a magazine page aimed specifically at women, there was also a sequel story. However, there were also critical voices such as that of James Joyce , who commented only two weeks after the launch:

"The 'Irish Independent' is really awful — I could not read any of the Celtic Christines except for the verse which seemed to be almost unbearably bad."

"The Irish Independent is really awful - I couldn't read any of the Celtic Christmas stories except the poems, which were almost excruciatingly bad."

There was also criticism that Murphy was investing too much money in an unprofitable newspaper business. He replied that he was happy to be able to spend money on his hobbyhorse. However, the success proved Murphy right, as sales soared to previously unknown heights for Ireland. In order to be able to follow this more closely, Murphy even had a record of exactly how many newspapers were actually sold and how many were being returned or given away. This practice was new at the time and a few years later it was also adopted in London. The sales figures measured in this way fell to 25,000 after several weeks, but reached 40,000 copies within three years. The Irish Independent also increasingly competed with local newspapers in the province, where the Dublin newspapers had previously arrived too late to find enough buyers. Thanks to the Irish Independent's new sales structure , it reached Waterford as early as 11 a.m., while the Irish Times and Freeman's Journal didn't arrive until late afternoon. This led to a death and amalgamation of local newspapers, so that in Waterford, for example, only the Munster Express , owned by Edward Walsh, survived. At the end of 1915 the Irish Independent had sales of 100,000 copies and annual profits were £ 15,000, increasing to £ 40,000 in 1918.

Organization of the 1907 International Exhibition

From 1876 Murphy was a member of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and due to his entrepreneurial success and extensive fame, he was elected to the Central Committee of the Chamber of Commerce in 1906. This was unusual because the majority of the organ was Protestants and opponents of an independently governed Ireland. In the Irish Independent , Murphy had the proposal for an international show in Ireland and as a result Murphy was asked by the Chamber of Commerce to consider the proposal. Murphy worked on it diligently and when a success was already on the horizon, some of his opponents accused him of doing this only to be knighted by Edward VII . After hearing this, Murphy publicly stated that he would not accept such an honor for hosting the exhibition. When Edward VII surprisingly actually came with the royal yacht on July 10, 1907, he also let the then Viceroy Lord Aberdeen know, but he failed to pass on his request. So it came to an embarrassing public scene when Edward VII had already called for the ceremonial sword and then Lord Aberdeen had the procedure aborted to the astonishment of the king. Murphy then sent an explanatory apology, which was accepted in a reply from Edward VII. In his letter, Murphy also stated his position that although he was in favor of a nationally governed Ireland, a common crown for both countries was right. Incidentally, the exhibition was an unrestricted success with around 2,750,000 visitors, which helped Murphy to be elected Vice President and later President of the Chamber of Commerce in 1911.

Confrontations with Dublin poets and artists

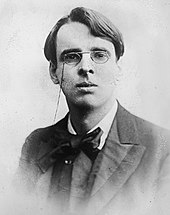

Regardless, Murphy was not well respected in Dublin's literary and artistic circles and was increasingly criticized publicly. Even when the Irish Independent joined the critics of JM Synge 's play The Hero of the Western World, premiered in 1907 , who saw only a disdain for the Irish people, bitter feelings were aroused, which were also directed against Murphy himself. As Synge passed away two years later and DJ O'Donoghue wrote an obituary in the Irish Independent describing Synge as promising but not fulfilling, and over-praised by its followers, WB Yeats bitterly noted in his diary:

“Yet these men came, though but in remorse; they saw his plays, though but to dislike; they spoke his name, though but in slander. "

“Meanwhile these gentlemen came, but they repented; they saw his pieces, but to their displeasure; they mentioned his name, but defamatory. "

As Morrissey points out, for Yeats Murphy represented a greedy, wealthy Catholic Irishman who not only replaced the Protestant upper class, but who also destroyed his hero Parnell, gave the Catholic clergy significant influence in Irish politics, and the dramatic one Genius had unforgivably reviled Synges. This impression was to intensify in particular in the case of Hugh Lane , who wanted to donate a more extensive art collection by modern French painters for a new art gallery to be created in Dublin. The British star architect Edwin Lutyens , won by Lane, designed a gallery that would span the Liffey in an arch , and the construction costs were estimated at £ 22,000. This met with great resistance, in particular because it was hardly financially possible with private funds and in Dublin only Arthur Guinness and Murphy could have financed such a project. Both offered some money but declined larger contributions, and Murphy criticized the project's proponents as "handful of amateurs" trying to push through a project for which there was no public demand and which would be of very little use to the ordinary people of Dublin .

The first disappointment that the project could not be financed privately came from W. B. Yeats around the turn of the year 1912/1913 in the poem To a Wealthy Man who promised a Second Subscription to the Dublin Municipal Gallery if it were proved the People wanted Pictures , which in the Irish Times on January 11, 1913. It was widely believed that the poem referred to Murphy. It wasn't until later in 1917 that Yeats made it clear that someone else was meant. According to Yeats commentator Jeffares, this can only mean Arthur Guinness. Murphy assumed it was related to him, however, and published a reply in the Irish Independent on January 17, 1913 , in which he pointed out that even donors have limited wealth and before public funds would be used for it , it would be better to listen to the Dubliners if they really want it. He recommended that such funds should be invested in new apartments for Dubliners living in poor conditions in the slums. However, this reasoning was viewed as hypocritical by proponents of the project because, as Yeats noted, the art gallery was endorsed by both union leader James Larkin and representatives of the slum workers.

On August 12, 1913, the Murphy-led Dublin Chamber of Commerce rejected the project in a statement. This and the ongoing campaign in the Irish Independent eventually led to the city government rejecting the project. Lane then gave up in September 1913, exasperated. Although Murphy was not alone, he was perceived by proponents of the project as the main culprit, not least because the Irish Independent had taken a clear stand. W. B. Yeats then published a volume of poetry entitled Poems Written in Discouragement , which appeared in 1913. Yeats wrote two of these poems on September 16, 1913. The first, entitled Paudeen ( slang term for Patrick , representing the simple Irish man), went directly against Murphy's reply that he spoke of Paudeen's pence . In his second poem entitled To A Friend Whose Work Has Come to Nothing (translation: For a friend, destroy their work was ), Yeats expresses its solidarity with Lady Gregory expressed that the project donations totaling £ 2000 America had recruited and, according to Yeats, was defeated by an opponent who was not ashamed of his lies:

| English version: | German translation by Norbert Hummelt : |

|

Now all the truth is out, |

Now that the truth is out, |

Labor dispute

Murphy took care of his workers and made sure they were paid fair. When he campaigned for the construction workers on strike in 1890, this was positively noted, so that he also received support from the unionist John Ward in the 1892 election. The weak position of the unions, which could be held liable for losses of companies on strike, changed in 1906 when the Trade Disputes Act was passed, which granted trade union leaders immunity therein. After James Larkin split from his original union, the National Union of Dock Laborers , he founded the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU). Here he tried in particular to win the railway workers in the region around Cork as members.

Employers, including Murphy, refused to tolerate union movement and agreed not to hire any employee who had previously been fired for union membership or support. Employers' worries soon increased when Larkin came to Dublin and teamed up with James Connolly , who had returned from North America in 1910 and advocated radical syndicalism . From May 1911, Larkin published his own newspaper, the Irish Worker and People's Advocate , which informed workers about their rights and in December 1911 had a circulation of 95,000.

Larkin was concerned not only with better conditions for the workers, but also with decisive changes in the balance of power. This was particularly evident in the strike organized by the ITGWU among workers in several woodworking companies. In order to put these companies under pressure not only through the immediate strike, Larkin urged the Great Southern and Western Railway not to transport goods from companies on strike . The board of directors, which also included Murphy, refused to do so because of the contractual obligations. Larkin then organized a railroad workers strike across Ireland. This was seen as a tremendous threat on the business side and the beginning of a class war. The Dublin Chamber of Commerce, significantly influenced by Murphy as Vice President, passed a resolution on September 21, 1911 to give the railway companies every possible support so that they can meet their obligations.

To put pressure on the union, Murphy locked out the railway repair workers and after only 38 of the locomotive drivers did not take part in the strike, Murphy brought in workers and members of the Royal Engineers from Britain to keep the railway lines running. This well-organized backlash, which ensured ongoing operations again, led to the demoralization of the striking workers. Murphy then stipulated that any worker who wanted to be reinstated should refrain from going on strike without notice and blocking the transport of unpopular goods. On October 4, 1911, the resistance collapsed and the workers agreed to the terms. As a result, an employers' organization was also founded in Ireland, which, under Murphy's leadership, was to become an important instrument in the dispute that followed two years later.

Larkin used the Irish Worker newspaper, which he controlled , to continuously attack Murphy. For example, a September 7, 1912 issue stated that Murphy was

"A creature who never hesitated to use the most foul and unscrupulous methods against any man, woman, or child, who in the opinion of William Martin Murphy stood in William Martin Murphy's way, a soulless, money-grubbing tyrant"

"A creature that never hesitated to use the most indecent and ruthless methods against any man, woman or child who, in the opinion of William Martin Murphy, stood in the way of William Martin Murphy, a soulless, greedy tyrant"

The success of this abuse was limited in Dublin at the time because Murphy was too well known. However, that was to change when, in the course of the subsequent strike, the dispute drew larger circles as far as London and these statements were then partially accepted without criticism. After a hiatus forced by illness, Murphy decided to rise to the challenge and invited the 700 workers on his Dublin trams to a gathering on July 19, 1913. In his speech, Murphy attempted to create a bond of mutual trust by emphasizing that he would have absolutely no objection to workers organizing among themselves, but would not allow them to join a rotten organization under a rotten leader, to allow Larkin to use him as a tool on his way to becoming a Dublin dictator. He called on workers not to take part in a strike organized by Larkin and referred to the railroad company's strike, which was suppressed within 19 days. He made it clear that the Dublin United Tramways Company would invest £ 100,000 and more to fight terrorism caused by strike. Murphy emphasized that in his more than 50 years as an employer he had not had any serious confrontation with his workers, instead he was connected to them, not as master of his servant, but as man to man, which earned him applause.

However, the situation changed only a month later when Murphy discovered that some of the delivery staff belonged to the ITGWU. He decided to fire these employees and have the other employees sign a declaration assuring that they would not take part in a strike organized by the ITGWU. This was taken as a declaration of war by Larkin, to which he countered on August 25, 1913 at a meeting at Beresford Place:

“Mr Murphy says there will be no strike. I tell Mr Murphy that he is a liar. Not only is there to be a strike on the trams […] we are going to win this struggle no matter what happens. "

"Mr. Murphy says there won't be a strike. I tell Mr. Murphy that he is a liar. There won't just be one strike on the trams [...] we'll win this fight no matter what. "

The announcement was followed by implementation the following day. Although only a minority of the tram drivers had joined the ITGWU, Larkin skillfully ensured maximum effect by having 200 employees taking part in the strike leave the trams without warning in the mornings, when there was a particularly large audience for the opening of the Dublin Horse Show other railways so that all the trams formed a long chain from College Green to the General Post Office . However, Murphy was able to restart operations quickly, as the striking workers could be quickly replaced by new hires.

Murphy, confident that he had won a decisive victory, tried to complete it by demanding a further explanation from his workers within a short period of time that they would never join the ITGWU and not support it in any way. This demand turned out to be excessive, as many workers were prepared not to join the ITGWU at first, but generally did not want to be denied this opportunity. By September 22nd, the number of workers affected by the strike or lockout increased to 20,000, of which 14,000 received strike pay .

The lockout put the striking and excluded workers in distress, so the British unions sent ships with food to Dublin. The refusal of employers, led by Murphy, to negotiate with the unions met with criticism and led to the establishment of a Board of Trade investigative committee chaired by Sir George Askwith. The final report of October 6, 1913, drawn up after a public hearing, criticized the declaration requested by Murphy as a restriction of personal freedom. Murphy did not give in, however, which drew increasing public criticism, including the voice of George W. Russell in Freeman's Journal :

“What did you do? [...] You determined deliberately in cold blood to starve out one-third of the population of this city, to break the manhood of the men by the sight of the suffering of their wives and the hunger of their children. [...] You may succeed in your policy [but] the men whose manhood you have broken will loath you [...] The children will be taught to curse you. "

"What have you done? In cold blood, they deliberately decided to starve a third of the city's population and to break the dignity of these men in the face of the suffering of their wives and the hunger of their children. [...] You may be successful in your approach, but the men who broke you will despise you [...] The children will be taught to curse you. "

Russell's prophetic words would come true thanks to two mistakes Larkin made. Larkin traveled through England and sought the support of the local trade unions in organizing solidarity strikes . The ruthless manner in which he tried to enforce this cost him quite a few followers. However, he finally got into trouble with his proposal to alleviate the plight of the working class children by sending them to England by ship. Despite the undoubtedly humanitarian intent, the announcement sparked a storm of protest, as suspicions were immediately raised that the Catholic children might be exposed to Protestant re-education.

Archbishop Walsh, who was previously on the side of the workers, felt compelled to take a public position against this plan. The Irish Independent's exaggerated allegations that Larkin was anti-clerical, anarchic and a Marxist socialist unexpectedly gained substance. This closed the ranks of employers again, some of whom had previously doubted the need for hardship. The increasing difficulty of the union in paying the strike money and the unusually harsh winter of 1913/1914 did the rest. In January 1914 the workers streamed back and accepted all the conditions.

Easter Rising 1916

The Easter Rising , which set itself the goal of military independence of Ireland from Great Britain , caught Murphy off guard. The Independent was the first newspaper to report on it after the uprising ended. In her editorial of May 4, 1916, written by editor-in-chief Harrington, presumably with Murphy's consent , she strongly condemned the uprising:

"No term of denunciation [...] would be too strong to apply to these responsible for the insane and criminal rising of last week."

"No accusatory word could be sharp enough not to apply to those responsible for the insane and criminal uprising of the past week."

The commentary also criticized the weaknesses of Birrell's government and Carson's irresponsibility and asked for mercy for the younger participants in the uprising.

Since there was considerable damage by the British artillery , which u. a. had destroyed two Murphy owned hotels, a meeting of affected Murphy owners was organized to seek compensation from the British government. While Murphy was visiting London on the matter, an editorial appeared in the Irish Independent that he was later wrongly accused of:

"Let the worst of the ringleaders be singled out and dealt with as they deserve."

"Let's tackle the worst ringleaders and treat them as they deserve."

In the same issue was a picture of trade unionist James Connolly with a caption indicating that he was still recovering from his wounds at Dublin Castle . He was executed two days later. Murphy later made it clear to Healy that he would never have approved this, but would not go public with it because he did not want to expose his employees.

Irish Constitutional Convention

An Irish constitutional convention was established by the British government in 1917 with the aim of developing a constitution for Ireland that would do justice to all interests as much as possible. The members invited should represent all groups in Irish society. However, members of Sinn Féin and some unions refused to participate. Murphy was invited by Henry Duke , Acting Chief Secretary , and took the seat after some deliberation. In the convention, Murphy sought independence on the model of Canada or South Africa . He opposed a division of Ireland with six predominantly unionist counties in the north and the remaining predominantly Catholic-nationalist counties and justified this with the fact that the respective minorities would be better protected in a government for all of Ireland. Although Murphy also spread his views in the Irish Independent , he couldn't get his way, so in the end he was only able to put together a minor opinion together with 21 other members including Archbishop Walsh . The majority opinion put forward by Chairman Horace Plunkett in April 1918 then no longer played a role, since at that time, after the German spring offensive, troops from Ireland were urgently needed for the western front . Since the British government originally intended to link the establishment of a national government for Ireland with compulsory military service , the timing of implementation seemed extremely unfavorable. Resistance to the threat of conscription, which was supported in particular by the Irish Independent and the Irish Catholic , led to increasing support for the national movement. When the war ended in November 1918, the conscription debate ended, but the struggle for independence organized by Michael Collins benefited greatly from the resistance.

Death and obituaries

Murphy then no longer took part in further political developments. He fell ill in June 1919 and died a week later on the afternoon of June 26th in Dartry Hall. Obituaries in the Irish and British press have been consistently positive, highlighting his business importance in particular. This public opinion in Ireland was to change dramatically when, after Irish independence, the leaders of the Easter Rising executed in 1916, including James Connolly, became heroes. No longer benefiting from his business talent, Dublin trams were quickly doomed. The Irish Independent, however, acquired the no longer successful Freeman's Journal in 1924 and has remained the Irish newspaper with the highest circulation to this day (as of 2011).

literature

- Arnold Wright: Disturbed Dublin: The Story of the Great Strike of 1913-1914 . Longman, London 1914 ( PDF [accessed June 13, 2011]).

- A. Norman Jeffares: A Commentary on the Collected Poems of WB Yeats . Macmillan, London 1968.

- Hugh Oram: The Newspaper Book: A History of Newspapers in Ireland 1649-1983 . MO Books, Dublin 1983, ISBN 0-9509184-1-5 , William Martin Murphy, a humane man, 1900–1915, pp. 94-122 .

- Thomas Morrissey: William Martin Murphy . Historical Association of Ireland, Dublin 1997, ISBN 0-85221-132-5 .

- Andy Bielenberg: Entrepreneurship, Power and Public Opinion in Ireland; the Career of William Martin Murphy . In: Chronicon . tape 2 , no. 6 , 1998, ISSN 1393-5259 , pp. 1-35 ( HTML [accessed June 13, 2011]).

- Henry Boylan: Murphy, William Martin . In: WJ McCormack (Ed.): The Blackwell Companion to Modern Irish Culture . Blackwell Publishers, 1999, ISBN 0-631-22817-9 , pp. 399 .

- Patrick Maume: Murphy, William Martin . In: Brian Lalor (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Ireland . Yale University Press, New Haven 2003, ISBN 0-300-09442-6 , pp. 752 .

Remarks

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 4; Bielenberg. Maume names Bantry as the place of birth. After Morrissey, the parents did not move to Bantry until 1846. Boylan names Bandon as the place of birth.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 75.

- ↑ See Maume.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 1.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 3.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 47-59.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 4-7.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 8.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 9.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 9-11.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 12.

- ↑ See Bielenberg.

- ↑ Wright's assessment, p. 70.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 14.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 15.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 18-21.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 23-24.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 27.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 28-29, and Oram, p. 103.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 28. The quote was originally published in the Irish People newspaper in 1900.

- ↑ See Oram, p. 103; John Horgan: The Irish Independent in McCormack, p. 304; Morrissey, p. 32.

- ↑ See Hugh, p. 103.

- ↑ See Oram, p. 105.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 33.

- ↑ From a letter from James Joyce to his brother Stanislaus dated January 19, 1905. The quote was taken from Sean Latham: “Am I a snob?”: Modernism and the novel. Cornell University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8014-8841-9 , p. 131, footnote 19.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 34.

- ↑ See Oram, p. 106.

- ↑ See Oram, pp. 108-109.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 35.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 36-37; Wright, pp. 75-77.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 38.

- ^ William Butler Yeats: Memoirs . Macmillan, London 1972, ISBN 0-333-13080-4 , pp. 201 .

- ^ Morrissey, p. 39.See also Jeffares, p. 123.

- ↑ See Jeffares, p. 124.

- ^ Morrissey, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ See Jeffares, pp. 123-126. Jeffares refers to a letter from Yeats dated January 1, 1913.

- ↑ See Jeffares, p. 133.

- ↑ a b Cyril Barrett, Jeanne Sheehy: Visual arts and society, 1900-1921 . In: William Edward Vaughan (Ed.): A New History of Ireland VI: Ireland Under the Union 1870-1921 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1989, ISBN 978-0-19-958374-4 , pp. 475-499 .

- ↑ The poems became better known in the volume Responsibilities: Poems and a Play, published in 1914 . In the collected works so these poems under the title Responsibilities and responsibilities summarized.

- ↑ See Jeffares, p. 132. Lady Gregory initially assumed that the poem was addressed directly to Lane. It was not until a note published in Later Poems in 1922 made it clear that the poem was addressed to Lady Gregory, whom Lane has supported in his cause. That is also the reason why Norbert Hummelt translated friend with "girlfriend".

- ^ William Butler Yeats: Yeat's Poems . Ed .: A. Norman Jeffares. Gill and Macmillan, Dublin 1989, ISBN 0-7171-1742-1 , pp. 211 .

- ^ William Butler Yeats, Marcel Beyer, Mirko Bonne, Gerhard Falkner: The poems: Newly translated by Marcel Beyer, Mirko Bonné, Gerhard Falkner, Norbert Hummelt, Christa Schuenke . Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 2005, ISBN 3-630-87214-X , p. 123 .

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 41-43.

- ^ See Morrissey, pp. 44-46.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 47.

- ↑ See Wright, p. 72.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 49.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 51.

- ↑ Cf. 52-53.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 54.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 54-56.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 61-62.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 63.

- ↑ See Morrissey, p. 64.

- ↑ See Morrissey, pp. 69-74.

- ^ See Morrissey, pp. 76-78.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Murphy, William Martin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Irish entrepreneur, publisher and politician, Member of the House of Commons |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 6, 1845 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Castletownbere |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 26, 1919 |

| Place of death | Dublin |