emigration

Emigration or emigration (from the Latin ex , e 'out' and migrare ' to wander') is leaving a home country permanently. Emigrants or emigrants leave their homeland either voluntarily or by necessity for economic , religious , political , professional or personal reasons. Emigration from one country is followed by immigration to another. The change of residence within a specified area is, however, called internal migrationdesignated. Usually individuals or individual families emigrate; in history there have also been emigrations of large groups of the population.

According to Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , everyone has the right “to move freely within a state and to freely choose where to stay” and “to leave and return to any country, including his own,”.

The term migration, which is not limited to emigration, is more common in science today . In addition to migration sociology, numerous social sciences are involved in migration research .

History of emigration

There has always been migration, for example motivated by existential threats ( famines , wars, natural disasters etc.) and / or by the hope for better economic conditions elsewhere. In research, one speaks of push and pull factors : Push factors in the country of origin result in (emigration) pressure, alleged or real advantages at the destination (host country) cause (immigration) so-called.

In this respect, every emigration has at least two aspects, namely

- the situation in the donating country: loss of population and talent, but also relief with scarce resources, as well as the acute loss of residents,

- the situation in the host country: problems of acculturation (especially language learning) and integration, but also immigration of workers, specialist knowledge and cultural diversity.

Europe

Early modern age

In the early modern period , forced emigration of entire population groups was more common than voluntary emigration. Examples of this are the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and the Moors after 1492, the floods of Protestant religious refugees since the 15th century, the forced resettlement of Indian tribes in reservations and later the establishment of criminal colonies .

During the Reformation and Counter-Reformation (1550–1750), many Protestants had to leave their homeland for reasons of faith, because since the end of the 16th century the principle of cuius regio eius religio was enforced more and more strictly by the princes. Those who did not want to convert to the denomination of their sovereign were forced to use the ius emigrandi (right to emigrate) and to emigrate. For example, Protestants in Bohemia emigrated in several waves from 1620 to around 1680.

In the late 17th century there were several waves of Huguenots emigrating from France. When King Louis XIV. In 1685 with the Edict of Fontainebleau , the Edict of Nantes abolished and prohibited the Protestantism that was particularly widespread in southern France, left thousands of members of the Protestant upper class their home and settled mainly in England , the Netherlands , Prussia and other Protestant territories of the Holy Roman Empire . Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg responded to the expulsion of the Huguenots with the Edict of Potsdam .

German language area

middle age

During the Middle Ages, people from the Holy Roman Empire migrated in various waves to the Slavic and Baltic populated areas east of it ( Ostsiedlung ). This partly led to a mixture, partly the German settlers remained a minority, partly the immigrants assimilated - for the most part, however, they resulted in a Germanization of the respective areas.

That is the reason for today's eastern expansion of the German-speaking area or its even greater eastern expansion until the Second World War. Large areas of today's East Germany as well as the eastern parts of Prussia did not belong to the area of the Holy Roman Empire around 1000 and only became German-speaking due to the waves of emigration from the area of the Reich (some never, e.g. parts of the former province of Posen ), later to the large Part also part of the Holy Roman Empire.

The settlement movement towards the east continued in modern times. However, under changed framework conditions (see below), and the target areas were often further to the east. They were not always connected to the German-speaking area and became islands of the German language (for example Volga Germans, see below).

Thirty Years' War and its post-war period

There were strong emigration movements for economic reasons after the Thirty Years' War , as labor emigrants from overpopulated Switzerland (especially from the cantons of Bern , Zurich , Thurgau and from areas of today's canton of St. Gallen ) and from Vorarlberg in the destroyed, sometimes deserted areas Settled in southwest Germany and helped to repopulate the devastated country.

18th century

Since the 15th century, some sovereigns such as the Counts of Wied or the kings of Prussia encouraged the settlement of religious refugees as part of their Peuplierungspolitik through discounts, because they hoped for impetus for their economy. In 1733 the Salzburg exiles from the Archdiocese of Salzburg were also accepted into Prussia.

In the second half of the 18th century, many people emigrated from the German states to the east: to Hungary , Romania and Russia , also here encouraged by sovereigns. In some settlement areas, the language and culture of the home country were preserved for centuries, as the settlements were largely isolated from the outside and, in particular, marriage connections with residents of the host country were almost impossible. Meanwhile the emigrants developed an important economic power.

People who emigrated for religious reasons moved to the United States of America as early as the 18th century in order to be able to live without reprisals with the freedom of religion granted there. This was of particular interest to small religious groups. The state of Pennsylvania in particular attracted people of all religious backgrounds. It was assumed that around 200,000 people emigrated from Germany to America in the 18th century alone.

19th century

In the 19th century, emigration in the German-speaking area, which began around 1820, reached a high point. There were several mass emigrations; they were related, among other things, to the economic development and / or demography of Germany . With regard to southwest Germany, one can distinguish three phases of mass emigration:

1816/1817

Due to the eruption of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia , one of the strongest known volcanic eruptions of all, so much ash was thrown into the atmosphere that it resulted in extremely wet, cold summers in the northern hemisphere (" year without a summer ") and the harvest of two Years failed. Therefore there was a great emigration movement. In southwest Germany, many people embarked on the Danube and settled in southern Russia ( Bessarabia , in the area around Odessa and around Tbilisi in the Caucasus ). A smaller proportion of the emigrants looked for a new home in the United States.

1845-1865

Again, pauperism and an ongoing economic crisis sparked mass emigration - the largest of the 19th century; now the streams of emigrants moved almost without exception to the United States. Large stretches of land were developed and settled there by fighting and driving out or exterminating the local Indians . The news of gold discoveries in California since 1848, which triggered the California gold rush , provided an additional incentive to emigrate .

Edgar Reitz describes the location and motives of the emigrants from the Hunsrück to Brazil in his feature film The Other Home .

In addition to the economically motivated emigration, there was also a political one around 1848, which reached its climax after the failed March Revolution . These emigrants are commonly referred to as Forty-Eighters ("forty-eight").

After 1855, emigration decreased and came to an almost complete standstill during the American Civil War (1861-1865). In 1916, Friedrich Naumann put the number of German emigrants who went to the USA between 1821 and 1912 at 5.45 million.

From 1816 to 1861 the Bavarian “register paragraph” was one of the main reasons for the predominance of Bavarian Jews in the first wave of Jewish immigration to the USA.

As part of the same wave of emigration, thousands of Germans emigrated to the Australian colonies . Their number is estimated at around 70,000 to 80,000 - up to the First World War. The Germans left a lasting mark on the history of the continent.

1880s

After 1880 there was another wave of emigration to the United States, which, however, no longer reached the strength of the other emigration movements. Most of the emigration via Bremen took place from Bremerhaven . An emigration center had been operated there since 1850 , so that emigration could take place with ships that had more draft.

Fraud in the Eastern European emigration market

Scams related to the care of emigrants are reported:

"In the years 1889/90, two Hapag agents who had run a business office in Auschwitz (Oswiecim) were on trial for ongoing fraud ."

The two agents Jacob Klausner and Simon Herz bribed railway conductors and officials, customs officers and even police officers on a large scale, it is reported. She had adorned the walls of her agency in Auschwitz with the German imperial eagle and a portrait of the emperor. There was a "telegraph" there - an old alarm clock. They talked about it with hostels in Hamburg, employers in the USA or even with the "Kaiser von Amerika". Police officers, who were respected and feared by emigrants, told - on behalf of the agents - that America could only be reached via Hamburg.

"Anyone who had a ticket or a passage instruction for a line other than Hapag was pressured and sometimes forced to let it expire and buy a" real "one from the agency."

These emigrants believed their emigration to be illegal. Many young men also wanted to evade conscription and did not have the courage to oppose the agency's practices. If they did, they would "be arrested, detained, beaten, and otherwise ill-treated by one of the bribed police officers until they gave in and followed the agents' instructions." This agency signed sailing contracts with approximately 12,400 people a year in the late 1880s. Widespread corruption in the Russian and also in the Austro-Hungarian administrative apparatus is held responsible for the functioning of the system.

“In addition, most of the emigrants who were at the mercy of a closed front of traders came from small villages and could neither read nor write. For these poor peasants, America was the great hope for a better life; they knew nothing about this country, but because they had so many wishes in it, they were ready to believe almost anything, especially the good news. […] The highly specialized, legally controlled system of professionally operated emigration agencies […] in Western Europe […] did not apply to the Eastern European emigration market. Unscrupulous agents there took care of the business on which the German shipping lines were now economically dependent. "

In order to protect the emigrants from exploitation by questionable agents and lodgers and to promote their integration in the immigrant country, aid and protection organizations such as the St. Raphaels-Verein (today Raphaels-Werk) were set up . The Raphaels Association was founded on September 13, 1871 by the "Comité for the Protection of German Emigrants" at the suggestion of the Limburg businessman Peter Paul Cahensly .

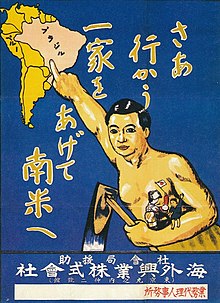

Image documents from around 1900

20th century to 1945

In the period of inflation after the First World War , whole groups emigrated to Argentina and southern Brazil (states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina ). German-speaking settlements also emerged here; a region in southern Brazil is still called Neu-Württemberg today.

After the takeover of the Nazi party in 1933 which set the persecution of Jews and a complete suppression of any political opposition (see z. B. DC circuit , Sopade / SPD in exile). People who recognized the danger early enough, had enough money and professional training, left the German Reich more or less voluntarily. The film metropolis Hollywood benefited from the influx of creative staff such as producers, directors and actors. Around 2,000 German-speaking filmmakers emigrated during the National Socialist era . The later classic film Casablanca (1942), for example, was predominantly cast with immigrant actors.

Famous emigrants in the 20th century were, for example, the natural scientist Albert Einstein , the physicians Philipp Schwartz , Rudolf Nissen and Erich Frank , the writers Thomas Mann , Heinrich Mann , Oskar Maria Graf , Erich Maria Remarque , Anna Seghers , Ernst Karl Winter , Arnold Zweig , Ludwig Renn and Bertolt Brecht , the politicians Willy Brandt and Ernst Reuter as well as the directors Billy Wilder , Fritz Lang and Douglas Sirk , who left Germany during the time of National Socialism and z. B. emigrated to the USA or Turkey . Among those who were forced to leave Germany during the Nazi era were many university professors, for example the Karlsruhe Professor of Physical Chemistry Georg Bredig , the Cologne Professor of Zoology Ernst Bresslau , the Halle Professor of Ancient Greek Philology Paul Friedländer , the Aachen Professor of Technical chemistry Walter Fuchs , the Frankfurt professor for physics Karl Wilhelm Meissner , the Berlin professor for physics Peter Pringsheim , the Breslau professor for physics Fritz Reiche , the Berlin professor Kurt Lewin u. a.

Around 10,000 emigrants from Germany and Austria served in the British army during the Second World War, fighting against the Nazi regime.

After 1945

After 1945 there was a cautious return migration ( remigration ) of individuals to the two German states. In western Germany they experienced open hostility in some cases for taking a direct or indirect stand against Nazi policies abroad. Some emigrants categorically refused to allow remigration; some of them never wanted to set foot on "German soil" again and proclaimed / justified this publicly.

On the other hand, there were also perpetrators of the Nazi regime from Germany among the emigrants who used the so-called rat lines to escape criminal prosecution . However, only a few Germans were able to emigrate until the summer of 1949, as political obstacles prevented emigration. These obstacles were only removed with the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany.

After 1945, many people from Germany emigrated to Australia and South America, for example, primarily because of the lack of economic prospects in the immediate post-war period, which only came to an end with the currency reform and the subsequent economic miracle . In addition, there were research restrictions issued by the Allies for scientists , which remained in force in Germany until 1955.

In the years 1945 to 1990 left millions of people the SBZ and their follow-state, the GDR as refugees overwhelmingly dissatisfied with the desired socialist model of society and into West Germany to live. Although the mass exodus could be stopped in 1961 by the construction of the Berlin Wall , it developed dynamically again in 1989 and accelerated the collapse of the GDR .

In 2015 around 140,000 Germans emigrated from their home country, in 2016 there were 281,000 and in 2017 there were 249,000 Germans.

The number of foreigners moving out of Germany every year is many times higher ( see : Germany's migration balance ).

Reasons for emigration

There is emigration in almost every country in the world for various reasons:

- because of better working and living conditions (especially for recruited workers, in Germany for example guest workers ; skilled workers who cannot find adequate work or who want to escape the high tax and social security burden). (They are also pejoratively called economic refugees.)

- Avoid the tax burden of people with high income or assets

- for political reasons (for example politically persecuted system critics and dissidents (mostly in dictatorships) or criminals persecuted by the police)

- for religious or linguistic - cultural reasons

- to increase the quality of life with a secure standard of living (e.g. emigration of pensioners due to better climatic conditions in the "sunny south" for example in Tuscany , Mallorca , the Canary Islands , or in the "Sunshine State" Florida )

- as refugees because of acute threats from war , civil war , natural disasters, famine or targeted displacement . (For more information, see Causes of Escape .)

- in earlier times due to enslavement

- due to family members and friends waiting in the destination country.

Forms of hindrance to emigration are border fortifications that make it impossible to leave secretly (e.g. the Iron Curtain in Central Europe or the border between the United States and Mexico ) but also a lack of finance to cover transport costs (poverty).

On the other hand, emigration can be subsidized by the state in order to reduce general unemployment, for example in the 1960s in Turkey, or to purposefully get rid of unwanted unemployed foreigners with their families, for example in Spain.

According to the Emigration Protection Act of 1975, business advice for those interested in emigration in Germany is an activity requiring a permit. The incentive to emigrate through commercial advertising is also prohibited. Support for emigrants by companies, international institutions or foreign governments with financial assistance is prohibited, unless the emigration takes place in states of the European Community. With this, the legislature wants to prevent the insecurity of those willing to emigrate from being exploited financially.

Emigration in different countries

There are classic emigration countries such as the countries of the so-called Second and Third World (developing countries). But people also emigrate from countries in the First World, for example due to labor migration from Poland, Romania and Turkey. In addition, there are also countries that do not have to limit emigration because their economic strength or other attractive living conditions mean that there is little or no pressure to emigrate, for example in the United States . Conversely, massive emigration, especially when it occurs together with a low birth rate, endangers the economic future of countries. This is currently the case in particular in some Eastern European countries such as Bulgaria , Romania , Hungary or Serbia , especially if emigration is greatly simplified by EU agreements on the free movement of persons . In these countries, long-term emigration is leading to a decline and rapid aging of the overall population.

Germany

In 2006, 18,242 Germans emigrated from Germany to Switzerland , 13,200 to the USA, 10,300 to Austria, 9,300 to Great Britain, 9,100 to Poland, 8,100 to Spain, 7,500 to France, 3,600 to Canada, 3,400 to the Netherlands and 3,300 to Turkey. A total of 144,815 Germans emigrated. During the same period, around 128,000 Germans moved from abroad to Germany. Overall, the number of net emigrations in 2005 was around 17,000, which corresponds to around 0.02% of the population. Furthermore, there are considerable differences within the Federal Republic of Germany, there is increased emigration from the northern federal states, while the development in Bavaria is exactly the opposite: the population is increasing continuously and emigration from native Bavaria is considered unusual.

In absolute terms - i.e. detached from the question of citizenship - 734,000 people emigrated from Germany in 2009. During the same period, 721,000 migrated to Germany. Of these, 606,000 were not German citizens.

In 2005, 160,000 Germans officially de-registered. The actual number (including those who do not unsubscribe) is estimated at 250,000. This is the highest registered emigration from the Federal Republic of Germany since 1950. It is particularly well-trained professionals who emigrate. Klaus J. Bade , professor of recent history at the University of Osnabrück and migration expert, speaks very pointedly of a "migratory suicidal situation" for Germany. Heinrich Alt , Federal Employment Agency executive board, says (with regard to employable people): “Currently, more residents are going abroad than foreigners are coming to Germany.” The geographical neighborhood, the German-speaking area, is of particular importance for German immigration to Switzerland and in particular Swiss tax law , which tax high assets less heavily than is the case in Germany. From a statistical point of view, Switzerland had an increasing immigration of Germans from year to year in the 2000s.

Museums in Bremerhaven, Hamburg and Oberalben are dedicated to the topic of emigration (see below) and at other locations, museum departments deal with regional waves of emigration or the expulsion of Jews from Germany, for example. Emigration is also a topic that is often discussed on television. For example, as a living history project in 2004, ARD showed a much-noticed journey through time by a total of 37 people who, like in 1855, crossed the Atlantic on the traditional sailing ship Bremen with the series “ Wind Force 8 ” . The media scientist Thomas Waitz stated in a study that deals with the problematization of emigration on television: “Unlike most other social phenomena, independent program formats with their own conventions and narrative strategies have developed with regard to emigration. “In 2009, 40,000 people left Germany and moved to Turkey, many of them well educated. For academics, a lack of sense of home is the most frequently cited reason for moving to Turkey with 41.3 percent. ( See also: People of Turkish origin in Germany # Emigration to Turkey .)

After 2008 was a record year with 161,105 German emigrants, officially only 154,989 Germans turned their backs on their homeland in 2009. Of these, 106,286 moved to other European countries, 23,462 emigrated to America, 14,592 to Asia, 5,198 to Africa and 4,894 to Australia and Oceania. In 2009, however, a total of 114,700 Germans returned to Germany. 74,417 of these came from European countries, 18,718 from America, 12,685 from Asia, 4,715 from Africa and 3,378 from Australia and Oceania.

In 2010, the emigration of Germans continued to decline slightly to 141,000. In the same year, however, 529,606 non-Germans left the country. The main emigration countries of the Germans were Switzerland (22,034), the USA (12,986), Austria (10,831) and Poland (9,434). 114,712 Germans returned to Germany. In addition, 683,529 non-Germans immigrated.

In 2015, 138,273 German emigrants were counted. The survey method was changed in 2016: Since then, all Germans who have deregistered and are not recorded anywhere else in Germany are counted as emigrants in the population statistics (Germans who go into hiding in the country are therefore counted, with a very small percentage here goes out). Up until 2015, emigration by Germans was only recorded as emigration if the new place of residence was known abroad. The number of Germans who emigrated in 2016 was 281,411 according to the new survey method; according to the previous survey method, it would have been around 131,000.

Austria

In Austria, the areas of the western Hungarian counties , which came to Austria in the course of the Burgenland conquest in 1921 , were the emigration country par excellence. According to estimates, around 40,000 Burgenlanders emigrated to the USA by 1923 , so that some villages lost more than 10 percent of their population. High birth rates and declining death rates due to improved medical care created a population overpressure in the villages, which was discharged by the migration to America.

Sweden

Between 1815 and 1850, the population in Sweden rose from 2.5 to 3.5 million, mainly due to the increase in rural areas. One solution to the resulting social problems was emigration, which began in 1840 and peaked in the 1880s. By 1930, more than 1.2 million Swedes had left the country.

Czechoslovakia

Many endangered people left the country between the incorporation of the Sudetenland as part of the Munich Agreement and the occupation by the Third Reich. Many of them had had to flee Germany before the Nazis.

After the war, many emigrants came back, but quite a few quickly left their homeland disappointed. In addition to the expulsion of the German population, the country also lost thousands of Czechs and Slovaks . After the communist seizure of power in February 1948, around half a million Czechs and Slovaks fled to the West until the revolution of 1989 (60,000 of them immediately after the February revolution in 1948, around 245,000 after the crackdown on the Prague Spring in 1968) and after the expulsions after the founding of the Charter 77 in 1977.

Museums, exhibitions

- The German Emigration Center is a museum in Bremerhaven with the central theme of the emigration of Germans - especially to the USA - at different epochs. (It opened in August 2005.)

- The Hamburg Emigration Museum BallinStadt (opened in July 2007).

- The Jewish Museum Berlin shows the visitor two millennia of German-Jewish history, the highs and lows of the relations between Jews and non-Jews in Germany. Here were immigration and emigration or expulsion / escape a recurring topos. The museum houses, among other things, permanent and temporary exhibitions as well as research facilities.

- The Emigration Museum Oberalben focuses in particular on emigration from the Palatinate .

- The Danube Swabian Central Museum in Ulm deals with the emigration to Hungary (today Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Croatia) in the 18th century, the multiethnic coexistence on the central Danube, and the flight and expulsion of Germans as a result of the Second World War.

- In the HAPAG halls at Steubenhöft in Cuxhaven there is a permanent exhibition "Farewell to America". Emigration via Hamburg / Cuxhaven with ships of the shipping company HAPAG to North America is discussed .

See also

- Age migration

- Labor migration

- Germans abroad

- Emigration fraud

- German overseas migration

- Share of immigrants by country

- Missler-Hallen / Bremen

- List of well-known German-speaking emigrants and exiles (1933–1945)

- Shipping of emigrants

literature

- Bruno Abegg, Barbara Lüthi, Association of Migration Museum Switzerland (ed.): Small Number - Big Impact. Swiss immigration to the USA. Verlag NZZ, 2006, ISBN 3-03823-259-9 .

- Klaus J. Bade: Germans Abroad - Foreigners in Germany, Migration Past and Present. Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-406-35961-2 .

- Simone Blaschka-Eick: To the New World. German emigrants in three centuries . Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-498-01673-9 .

- Hans-Ulrich Engel: Germans on the move. From the medieval east settlement to the expulsion in the 20th century. Olzog, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-7892-7173-X .

- Thomas Fischer, Daniel Gossel (ed.): Migration in an international perspective. allitera, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86906-041-5 .

- Dirk Hoerder: Cultures in Contact: World Migrations in the Second Millennium . Duke University Press, Durham, NC 2002.

- Dirk Hoerder, Diethelm Knauf (Hrsg.): Departure to foreign countries, European emigration overseas . Edition Temmen, Bremen 1992, ISBN 3-926958-95-2 .

- Dirk Hoerder: History of German Migration . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58794-8 .

- Jour-Fixe-Initiative Berlin (Ed.): Fluchtlinien des Exile . Unrast Verlag, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-89771-431-0 .

- Evelyn Lacina: Emigration 1933–1945. Socio-historical presentation of German-speaking emigration and some of their countries of asylum based on selected contemporary testimonies . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-608-91117-0 .

- Manfred Hermanns : Worldwide service to people on the move. Advice and welfare for emigrants from the Raphaels factory 1871–2011. Friedberg: Pallotti Verlag 2011. ISBN 978-3-87614-079-7 .

- Walter G. Rödel, Helmut Schmahl (Hrsg.): People between two worlds. Emigration, settlement, acculturation. WVT Trier, Trier 2002, ISBN 3-88476-564-7 . (Focus on German emigration to North America in the 18th and 19th centuries)

- Joachim Schöps (Ed.): Emigrate. A German dream. Rowohlt TB-V, 1986, ISBN 3-499-33028-8 .

- Ljubomir Bratić with Eveline Viehböck : The second generation , migrant youth in German-speaking countries, Innsbruck: Österr. Studien-Verlag 1994, ISBN 3-901160-10-8

On the emigration of German artists into the American film industry:

- Marta Mierendorff, Walter Wicclair (ed.): In the limelight of the "dark years". Essays on theater in the “Third Reich”, exile and post-war (Sigma-Medienwissenschaft, 3). Ed. Sigma, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-924859-92-2 .

To portray emigration on television in Germany:

- Thomas Waitz: Emigrate. Home, foreign, television . In: Claudia Böttcher, Judith Kretzschmar, Markus Schubert (eds.): Heimat und Fremde. Self, external and role models in film and television . Munich 2008 ( online , PDF; 412 kB).

Web links

- Graphics and text: Germany: Immigration and Emigration, 1984-2016 , from: Figures and facts: The social situation in Germany , Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

- Graphics and text: Europe: Migration balance, 2010-2015 , from: Figures and facts: Europe , Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

Individual evidence

- ↑ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 13 , December 10, 1948, on Wikisource .

- ↑ See already Erich Stern : Emigration as a psychological problem. Self-published, Boulogne-sur Seine 1937; reprinted in: Uwe Wolfradt, Elfriede Billmann-Mahecha, Armin Stock (eds.): German-speaking psychologists 1933–1945. An encyclopedia of persons, supplemented by a text by Erich Stern. Wiesbaden 2015, pp. 503–551.

- ^ Eberhard Fritz: War-related migration as a research problem. On immigration from Austria and Switzerland to southwest Germany in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. In: Matthias Asche / Michael Herrmann / Ulrike Ludwig / Anton Schindling (eds.): War, the military and migration in the early modern times (rule and social systems, volume 9). Münster 2008. pp. 241-249.

- ^ Testimonies to Rhenish History 1982 (hopman44).

- ^ Max Döllner : History of the development of the city of Neustadt an der Aisch until 1933. Ph. CW Schmidt, Neustadt ad Aisch 1950. (New edition 1978 on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Ph. CW Schmidt Neustadt an der Aisch 1828-1978. ) P. 466 f . (on the emigration from Aisch valley villages to America).

- ^ Karl Stumpp : The emigration from Germany to Russia in the years 1763 to 1862. 5th edition. Stuttgart 1991.

- ^ Friedrich Naumann: The American neutrality. In: Friedrich Naumann (Ed.): Help. Weekly for politics, literature and art. 22nd year, Berlin-Schöneberg 1916, p. 125 f.

- ↑ Ursula Gehring-Münzel: The Würzburg Jews from 1803 to the end of the First World War. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. Volume III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, pp. 499-528 and 1306-1308, here: pp. 500-504.

- ^ Germans in Australia

- ↑ a b c d Agnes Bretting: From the old to the new world. In: Dirk Hoerder, Diethelm Knauf (eds.): Departure to the foreign, European emigration overseas . Edition Temmen, Bremen 1992, p. 94 f.

- ↑ In his book "Kaiser von Amerika", which won the 2011 Book Prize for European Understanding, Martin Pollack tells of a time of crisis in which there was no room for Galicia romanticism. ( Memento from November 30, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Helmut G. Asper: Something Better Than Death - Film Exile in Hollywood. Schüren Verlag, Marburg 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Werner E. Gerabek : Emigration of German Doctors to Turkey. In: Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 346-348.

- ↑ Peter Leighton-Langer: X stands for unknown. Germans and Austrians in the British armed forces during World War II . Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-87061-865-5 .

- ↑ Stefan von Borstel: Why the best leave Germany. In: world. June 2, 2015, accessed August 12, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Marcel Leubecher: More and more German left the country. In: world. March 13, 2015, accessed August 12, 2018 .

- ↑ 281,000 Germans have emigrated: 281,000 Germans have emigrated. In: world. March 14, 2018, accessed April 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Marcel Leubecher: Germany gains as many inhabitants through migration as through births. In: world. October 15, 2018, accessed June 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Spanish Ministry of Labor and Immigration: (client): PDF . October 2008.

- ↑ elpais.com: Corbacho estima que unos 20,000 inmigrantes se acogerán al plan de repatriación con incentivos , accessed on May 6, 2011.

- ↑ Germans are drawn to Switzerland. In: NZZ. August 19, 2006, accessed on March 9, 2014 (figures from German emigrants).

- ↑ Wave of emigration? There is not any! ( Memento from May 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ More emigrants than immigrants . In: Frankfurter Rundschau , May 26, 2010.

- ↑ German Emigration: The Bye-AG. on: Spiegel online. August 11, 2006.

- ↑ Tagesschau from July 3, 2006: Politics overslept the emigration trend ( Memento from April 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Tagesschau from July 6, 2006: More German citizens than ever before are emigrating (tagesschau.de archive)

- ^ Escape from Germany: Greatest wave of emigration in history. on: Spiegel online. July 22, 2006.

- ↑ Berlin's economy is booming: 28,000 new jobs. ( Memento of July 3, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on: Berliner Morgenpost. June 28, 2007.

- ↑ From Bremerhaven to New York in autumn 2003 - homepage of the film series wind force 8 ( Memento from May 24, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Thomas Waitz: Emigration. Home, foreign, television. In: Claudia Böttcher, Judith Kretzschmar, Markus Schubert (eds.): Heimat und Fremde. Self, external and role models in film and television . Munich 2008, p. 189 ( online , PDF; 412 kB; accessed on December 22, 2020).

- ↑ emigration. Why well-educated Turks are leaving Germany. Welt Online, October 30, 2010, accessed November 1, 2010 .

- ↑ Emigration to Germany in 2009. at: auswandern-info.com

- ↑ Germany emigration in 2010. at: auswandern-info.com

- ↑ Where the Germans emigrated to in 2010. on: auswandern-info.com

- ↑ Return to Germany at: auswandern-info.com

- ↑ American migration of the Burgenlanders , website regiowiki.at, accessed on January 17, 2015.

- ↑ American migration of the Riedlingsdorfer , website regiowiki.at, accessed on January 17, 2015.

- ↑ List of those who have emigrated from Riedlingsdorf , website regiowiki.at, accessed on January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Walter Dujmovits: The migration of the Burgenlanders to America , Verlag Desch-Drexler, Pinkafeld 1992, pp. 15 and 16.