Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was a month-long rebellion by the Irish people against British rule in the Kingdom of Ireland for the independence of Ireland.

prehistory

The predominantly Catholic population of Ireland was excluded from many areas of life by the Penal Laws . In Ireland, for example, a Catholic could neither hold public office nor be drafted into the military, participate in elections or own weapons. These penal laws could also be applied to Protestants who opposed the Church of Ireland , so British rule tried to enforce their claim in Ireland.

Within the Irish population, especially among the educated upper class, the ideas of the French Enlightenment and the American War of Independence received a lot of attention and led to a frequent preoccupation with liberal ideas.

With France's support for American independence, the British crown was forced to ship large numbers of troops to North America. In order not to surrender their property in Ireland defenselessly to the European enemies and thus to allow a bridgehead for later invasions on the British motherland, the British crown called out a vigilante group in 1778, the so-called Irish Volunteers .

Irish volunteers

This vigilante took on both Protestants and Catholics, which was remarkable in that the vigilantes were armed, which was contrary to the existing regulations of the Penal Law.

The Irish Volunteers quickly developed into a political power factor in Ireland, so that in 1779 they already had 100,000 members, exercised their influence for the first time and wrested a free trade agreement between Ireland and England from the British crown, which put an end to the disadvantage of the Irish Products.

In 1782 there was another trial of strength between the Irish Volunteers and the British Crown, which resulted in the Irish being given greater powers over their own parliament. The Irish themselves speak of the constitution of 1782 in this context.

As early as 1783, after the war in North America was over, the vigilantes were of little use to the British Crown, but it was not until 1793, a year after the outbreak of the war against France, that they were banned and dissolved by law. Parts of the Irish Volunteers were supporters of the French Revolution and founded the Society of United Irishmen after the dissolution of the vigilante group.

Society of United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was an association of Irish people who were dissatisfied with the realities in Ireland and permeated by the ideas of the French Revolution. They founded the Society in 1791 to jointly find a way to meet the needs of Irish society for participation and equality between Catholics and Protestants on the one hand, and in the relationship between Ireland and Great Britain on the other.

With the outbreak of the war against France in 1793, the Society of United Irishmen was classified as subversive and banned by the British Crown.

The members then went underground and continued to meet in secret. At the same time, an alliance was formed with the Defenders group , another political alliance that had set itself the political and religious freedom of Ireland as a goal and also established contact with the French government. As a result, there were repeated small uprisings that the British Army put down, sometimes with the help of local militias.

The leaders of the Society of United Irishmen knew that their ideas could only be successfully implemented with the help of an armed force and urged the French government to support the Society of United Irishmen's request.

The unsuccessful rebellion of 1796

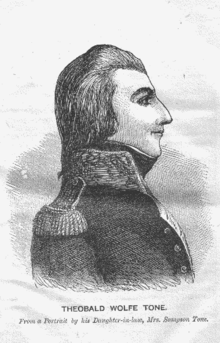

The leader of the Society of United Irishmen, Theobald Wolfe Tone , traveled to France from his American exile and asked the French government for support against the British. The French government then dispatched a force of 15,000 French soldiers under the orders of Lazare Hoche .

Due to adverse weather conditions and several shipwrecks, the army returned without having occupied Irish soil, which made the rebellion a failure from the start.

The strength of the armed forces showed the British how serious the situation was in Ireland and prompted the British government to take further measures against the Irish people. As a result, martial law was imposed on Ireland, attacks on Catholics and Protestant supporters of the Society of United Irishmen and the establishment of organizations that opposed the Society of United Irishmen, such as the Orange Order , supported.

In order to gain influence over the Catholic population, the British government tried to win the Irish episcopate on its side. As early as 1793, Catholics were allowed to vote with restrictions and to enroll in universities. In 1796 the British Government established Maynooth College for the Catholic Church of Ireland to train Catholic clergy. Until then, these had been trained abroad, mostly in France.

The measures had an effect on the episcopate, so that supporters of the ideas of the Society of United Irishmen were threatened with excommunication . This was all the easier for the episcopate since the French revolution made the Catholic Church in opposition to the French.

1798 rebellion

Pressure from the British government was taking effect, placing increasing pressure on the leadership of the Society of Irishmen and its allies. Through informants in the ranks of the rebels and betrayal by the population, the leadership level of the rebels had been decimated and at the same time led to a dispute over the direction within the movement. Ongoing arrests and convictions continued to weaken the moderate wing within the Society of United Irishmen. This wing wanted to wait for the start of the rebellion until support from the French arrived. The militant wing, on the other hand, wanted to strike immediately and take advantage of the broad support of the population and the need of the people.

It was decided on May 23rd to start the rebellion by conquering Dublin and then continuing the rebellion in the counties around Dublin to make it impossible for the British to retake Dublin.

Through betrayal and the work of informants, the British Army found out about the project immediately before the start and occupied all the prearranged places in Dublin and prevented the rebels from conquering the city. Despite this unexpected setback, the insurgents managed to take the surrounding counties around Dublin. The news of the rebellion spread and spread to other counties. In some cases the British army was able to put them down quickly, and in some cases the concern of loyal citizens of the counties resulted in all of the people suspected of the rebellion being killed or arrested. In return, the rebels' anger was usually directed against wealthy Protestants. Thus the rebellion quickly developed into a civil war. The British Army was able to put down most of the uprisings after a few days, preventing a full rebellion across the country.

Only County Wexford could be held by the rebels for a long time, but with the defeat at the Battle of Vinegar Hill on June 21, when 20,000 British soldiers invaded the county, the rebellion ended. Isolated troops managed to escape and they fought isolated skirmishes with the British Army until July 14, but with the fall of County Wexford the rebellion was effectively over.

On August 22, 1798, 2,000 French soldiers landed in County Mayo and helped about 5,000 insurgents there to defeat the British troops in the Battle of Castlebar . After this victory they proclaimed the Republic of Connaught, which lasted until the British victory over the rebel and French forces on September 8th.

Another unit of French troops wanted to land in County Donegal on October 12, 1798, but the British Navy was still able to intercept the units at sea, so these French troops never entered Irish soil. Among them was Theobald W. Tone, who was arrested by the British and sentenced to death.

aftermath

Sections of the Society of United Irishmen went underground and tried to continue the fight against the British, but most gave up in 1800 when the Act of Union was passed. This came into force in 1801 and united the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of England to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The newly won rights and freedoms of the Irish through the Act of Union make the revolution of 1798 seem like a success for the rebels, but at the same time the rebellion also led to a split in the religious population, in which Protestants and Catholics joined forces for an independent Ireland at the beginning fought that continues to this day and has continued to come to a head.

literature

- Nancy Curtin: The United Irishmen . Oxford 1994, ISBN 0-19-820322-5 .

- James Lydon: The making of Ireland . London 1998, ISBN 0-415-01347-X .

- Elaine McFarland: Ireland and Scotland in the age of Revolution . Edinburgh 1994, ISBN 0-7486-0539-8 .

- John Ranelagh: A short history of Ireland . Cambridge 1983, ISBN 0-521-24685-7 .

- Marian Richling: To make all Irishmen - citizens; all citizens Irishmen? The Genesis and Failure of Republican Nationalism in Ireland . Bielefeld 2005.

- Eckhardt Rüdebusch: Ireland in the age of revolution . Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-631-42233-4 .

- Jörg Schweigard: Ireland: Green and Free . In: Die Zeit 29/2003, 10 July 2003.