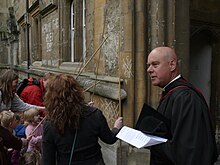

Beating the Bounds

Beating the Bounds is a ritual practiced in England, Ireland, Wales and Scotland to this day, in which the boundaries of a parish or other area marked with boundary stones are paced and the boundary stones are struck with sticks or branches. It traditionally takes place during the prayers (English rogationtide ) between the fifth Sunday after Easter (Rogate) and Ascension Day.

history

Prayer processions before the Reformation

The ritual goes back to the time of the Anglo-Saxons , i.e. the time before the conquest of England by the Normans . Originally it was a request procession along the municipality border, i.e. mostly through the field corridor surrounding a place, where crosses, bells and banners were carried. These processions were therefore also known as "Gang Days" or "Cross Days". The procession stopped at crossroads to say prayers and the All Saints litany was sung during the procession . The aim of the requests and prayers was to drive out evil spirits from the community and to ask for a good harvest. Symbolically, the procession meant a demarcation between the different communities and at the same time a reassurance of one's own identity and belonging to the respective communities. The procession usually ended with a common meal to which all participants were invited.

Attitude of the Reformation to processions

The English Reformation basically rejected processions as superficial popular amusement with no deeper meaning and the prayers at crossroads as idolatry. The crossroads at which the processions usually stopped have often been removed. The prayer procession in the Rogationtide was regarded by some reformers as an archaic and superstitious ritual and significantly fewer corridors were walked around immediately after the Reformation . However, corridors were not generally forbidden and the Elizabethan Book of Homilies of 1563, a kind of treatise on the principles of the Reformed faith that appeared in three versions, even contained a sermon specifically dedicated to the Rogationtide, unlike the version of 1547 . This was justified with the fact that the corridor in the praying week should serve the parishioners to preserve the knowledge of the parish boundaries. What was then referred to as "Beating the Bounds" is the only procession that was and is still practiced in England after the Reformation.

Beating the Bounds after the English Civil War

Church books and visitation reports document that "Beating the Bounds" was very common well into the 17th century. Documents from the second half of the 17th century show that the tradition and rituals were refined and confirmed during this time, as the idea of keeping the community boundaries present in the consciousness of the residents of an area was generally considered to be sensible. City communities provided the participants with specially purchased white sticks, which were used to hit the boundary stones, while in rural areas not only sticks, but also pipes and tobacco were provided. From this time comes the tradition that not only boundary stones but also children were hit with sticks so that they could memorize the position of the boundary stones. The modern "Beating the Bounds" emerged from the old cross procession.

procedure

In the pre-Reformation period, all parishioners, women and men, took part in the procession. It was considered improper to stay away from the procession. In some cases, the congregations even paid individual members to carry the banners forward while they were around. This changed fundamentally after the reform. The Royal Injunctions issued by Elizabeth I in 1559 now describe the ritual in such a way that " the bounds were to be walked only by the subtantialest men of the parish " (that the boundaries of the community should only be paced by the most important men of the community ). The regulations of the Archbishop of York from 1571 stipulated that in addition to these only "the parson, vicar or curate" and "churchwardens", d. H. the clergy and clergy should attend. The Archdeacon of Berkshire, however, insisted in 1615 that "Beating the Bounds" next to the clergy "a sufficient number of the parishioners of all sorts, aswel of the elder as younger sort, for the better knowledge of the circuits and bounds of the parish "That is, a sufficient number of parishioners of all kinds, both old and young, should attend to increase knowledge of the scope and limitations of the church.

The municipal boundaries were not only important for the membership of the residents in the municipality, but also to clarify responsibilities between different municipalities. Poor welfare laws stipulated that the congregations were obliged to take care of impoverished congregation members and that they could also demand taxes from their other members. Beating the Bounds made sure parishioners knew who to contact in an emergency.

Tradition revived

Today the ritual is still or again practiced in Oxford and London. The congregation of All Hallows by the Tower in London , whose southern parish boundary is in the middle of the Thames , must board a boat to visit the southern parish boundary and hit the boundary marker in the water. Every three years there is a ritual battle against the Yeomen Warders of the London Tower to commemorate an old border dispute with the Tower that led to an uprising in 1698. In Oxford, groups from the parishes of St. Michael at the Northgate and St. Mary the Virgin are among others with willow branches and traverse the grounds of Brasenose College .

literature

- Alexandra Walsham: Beating the Bounds and the Beauty of Holiness: Liturgical Rites, Laudianism and the Resacralization of Space. In: The Reformation of the Landscape. Religion, Identity, and Memory in Early Modern Britain and Ireland. Oxford, 2011, pp. 252-273.

- Steve Hindle: Beating the Bounds of the Parish: Order, Memory, and Identity in the English Local Community, c. 1500-1700. In: Halverson / Spierling: Defining community in early modern Europe. Aldershot / Burlington, 2008, pp. 205-227.

Web links

- Beating the Bounds in Oxford (Video)

- Beating the Bounds in All Hallows By the Tower

- Archival footage of Beating the Bounds from the first half of the 20th century

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Steve Hindle: Beating the Bounds of the Parish: Order, Memory, and Identity in the English Local Community, c. 1500-1700 . In: Halverson / Spierling (eds.): Defining community in early modern Europe . Aldershot / Burlington 2008, p. 205-206 .

- ^ A b Alexandra Walsham: Beating the Bounds and the Beauty of Holiness: Liturgical Rites, Laudianism and the Resacralization of Space. In: The Reformation of the Landscape. Religion, Identity, and Memory in Early Modern Britain and Ireland . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, pp. 252 .

- ^ A b Steve Hindle: Beating the Bounds of the Parish: Order, Memory, and Identity in the English Local Community, c. 1500-1700 . In: Halverson / Spierling (eds.): Defining community in early modern Europe . Aldershot / Burlington 2008, p. 207-208 .

- ^ Steve Hindle: Beating the Bounds of the Parish: Order, Memory, and Identity in the English Local Community, c. 1500-1700 . In: Halverson / Spierling (eds.): Defining community in early modern Europe . Aldershot / Burlington 2008, p. 208-209 .

- ^ Steve Hindle: Beating the Bounds of the Parish: Order, Memory, and Identity in the English Local Community, c. 1500-1700 . In: Halverson / Spierling (eds.): Defining community in early modern Europe . Aldershot / Burlington 2008, p. 210-211 .

- ↑ https://www.bnc.ox.ac.uk/about-brasenose/history/215-brasenose-traditions-and-legends/416-beating-the-bounds. Retrieved September 16, 2016 .

- ↑ http://www.allhallowsbythetower.org.uk/whats-on/beating-the-bounds/. Retrieved September 16, 2016 .

- ↑ http://londonist.com/2015/05/beating-the-bounds-is-one-of-londons-oddest-traditions. Retrieved September 16, 2016 .

- ↑ https://www.bnc.ox.ac.uk/about-brasenose/history/215-brasenose-traditions-and-legends/416-beating-the-bounds. Retrieved September 16, 2016 .