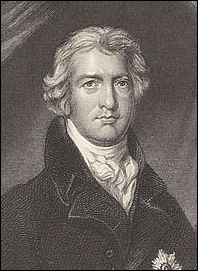

George IV (United Kingdom)

Georg August Friedrich ( English George Augustus Frederick ; * August 12, 1762 in St James's Palace ; † June 26, 1830 in Windsor Castle ) was from 1820 to 1830 as George IV. King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover . As early as 1811 he exercised the office of regent , since his father Georg III , who was probably suffering from porphyria . was incapable of governing . His brother succeeded him as Wilhelm IV on the throne.

Historical classification

Georg IV will be remembered by posterity, among other things because of his dissolute and extravagant lifestyle, the broken relationship with his father and his failed marriage with his cousin Caroline von Braunschweig . Although he had already entered into a secret marriage with the twice widowed and Catholic Maria Fitzherbert in 1785 , he married Caroline von Braunschweig in 1795. At that time, his debts were so high that only a legal marriage and the associated increase in his appanage before him could save personal ruin. However, the connection failed just a year later. Shortly after their daughter Princess Charlotte Augusta was born, the then Prince of Wales decided to live apart from his official wife. In 1820, his attempt to officially dissolve this marriage through a parliamentary resolution caused a sensation. Large parts of the population showed solidarity with the queen in this dispute. Because of his extravagance and gambling addiction, his affairs and his corpulence - in 1797 he weighed 111 kilograms and in 1824 his waist circumference was 124 centimeters - George IV was a popular target of the British press and caricaturists.

The Regency art era is closely linked to George IV. The beginning of this era, which lasted until 1834, is generally dated to the arrival of the then Prince of Wales in his seat at Carlton House . After his accession to the throne, he had Buckingham Palace significantly expanded and made it a royal residence. Other London attractions such as Regent Street , Regent's Park , Trafalgar Square and the new construction of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton by John Nash can be traced back to the initiative of George IV.

Childhood and adolescence

George was born in St James's Palace as the eldest son of King George III. born from the house of Hanover and Sophie Charlotte von Mecklenburg-Strelitz . The couple had seven more sons (two of whom died early) and six daughters over the next 21 years. Georg received the titles Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay at birth . A little later he was also appointed Prince of Wales . On September 8 of the same year he was baptized by Thomas Secker , Archbishop of Canterbury . Godparents were his uncle Karl II, Duke of Mecklenburg , his great-uncle William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and his grandmother Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg .

George III and his wife preferred a simple and humble lifestyle to court life in London. The couple's preferred residence was their country estate, Kew Palace , where King George III. he mainly devoted himself to his hobby, agriculture, which earned him the nickname “Farmer George” among the British population. He personally laid down the guidelines according to which the upbringing of children should be oriented. The upbringing was strict and sober and emphasized a sense of duty and fear of God. His eldest son Georg was a very talented and intelligent student who learned French , German and Italian , played the cello and, in addition to taking lessons in subjects such as law , history , mathematics and religion, also received drawing lessons . George III early on, however, reprimanded the heir to the throne for his easily influenced character and his tendency to idleness. The following letter from George III is characteristic. to the heir to the throne, who was 17 at the time:

“You can have dinner in your apartment on Sundays and Thursdays, but I cannot afford this more often […] I will not allow participation in balls and parties that take place in private houses […]. As for masquerades, you know that I find them unsuitable for this country [...] If I ride out in the morning, I expect you to accompany me. I have no objection if you ride alone on the other days, provided that it is for exercise and not for lounging around in Hyde Park [...]. "

From the age of sixteen, the heir to the throne began to rebel increasingly against his parents. He frequented more and more prominent Whigs such as Charles James Fox , who opposed the conservative government of George III. stood. These circles also encouraged his gambling addiction, his affinity for women's stories, and his dissolute lifestyle. Even before he came of age, he caught the attention of London society through an affair with the young Mary Robinson . Mary Robinson, best known today as a poet and early feminist, experienced her first successes as an actress at that time and was also called " Perdita " after one of her roles . Her counterpart in this role was the prince "Florizel". Mocking verses and caricatures about "Perdita" and "Florizel" were understood long after the end of the affair in 1783 as an allusion to the affair between the actress and the heir to the throne.

The financial consequences of the short affair caused public anger in particular: the heir to the throne bought the young actress's affection by promising her lavish financial donations. He wanted to pay her this as soon as he reached the age of majority. Mary Robinson ultimately received only a fraction of the originally promised apanage, but received a one-time payment of £ 5,000 after the end of the affair and was later able to enforce an annual pension of £ 500 when she threatened to publish his love letters. The size of the payments was considerable: a British lieutenant colonel like Mary Robinson's later lover Banastre Tarleton was receiving an annual wage of 346 pounds at that time, and Jane Austen stated that a curate with 140 pounds would have a modest but adequate annual income.

Prince of Wales

In 1783 Georg came of age. He received a one-time payment of £ 60,000 from the British Parliament and an annual allowance of £ 50,000. He used his legal age to evade the strict life guidelines of his parents and move into Carlton House, his own residence in the center of London .

In 1784 the Prince of Wales fell in love with Maria Fitzherbert , a twice widowed Catholic Irish woman. Her first husband Edward Weld had died in 1775, her second husband Thomas Fitzherbert in 1781. Marriage to her was actually ruled out for the Prince of Wales, as the Act of Settlement clearly stipulated that a marriage with a Catholic spouse was excluded from the Succession to the throne would result. A no less great obstacle was the Royal Marriages Act , according to which the marriage of a member of the royal family could only be carried out with the consent of the king. There is no doubt that George III. never given his blessing to the connection with Maria Fitzherbert. Despite this, the couple entered into a secret marriage on December 15, 1785 . Legally, the marriage was invalid due to the king's lack of consent. Nevertheless, Maria Fitzherbert was convinced that she was the rightful wife of the Prince of Wales, since, from her point of view, ecclesiastical law took precedence over state law. For political reasons, the connection remained secret and Maria Fitzherbert had promised not to let it be known in public.

Due to his lavish lifestyle, the Prince of Wales was now heavily in debt. His father refused to pay for these debts, forcing Prince George to move out of his Carlton House residence and live in Maria Fitzherbert's home. In 1787, political allies of the heir to the throne introduced a bill to the House of Commons to pay off the prince's debts with a financial contribution from parliament. At this point, rumors were already circulating that the relationship with Maria Fitzherbert was more than an affair. However, the exposure of the illegal marriage would have caused a scandal, thwarted parliamentary repayment of the princely debts and possibly the exclusion of the Prince of Wales from the line of succession. With the prince's approval, Charles James Fox, the leader of the Whigs, described the rumors circulating in front of Parliament about an existing marriage to Maria Fitzherbert as malicious slander. Maria Fitzherbert was so upset by this strict public denial of the marriage that she considered ending the relationship with the prince. Prince George then asked another Whig, Richard Brinsley Sheridan , to rephrase Fox's vehement statement in more reserved terms. Parliament was at least so pleased with the declaration that it granted the Prince a grant of £ 161,000 to repay his debts and an additional £ 20,000 to properly furnish Carlton House . At the same time, the annual donations were increased by £ 10,000.

Regency crisis of 1788

Today there is broad consensus that George III. suffered from the metabolic disease porphyria . This hereditary disease is associated with various symptoms and often progresses in attacks. Mental confusion is one of the possible manifestations of this disease. Since the British system of government was still tailored to the king, his first serious illness was accompanied by a serious government crisis.

George III suffered from mental confusion throughout the summer of 1788, but was able to arrange for the opening of parliament to be postponed from September 25 to November 20. During this break in the session, however, the king's condition continued to deteriorate. When parliament was due to meet again in November, the king was no longer able to deliver the speech from the throne , which is mandatory at the beginning of a parliamentary term . This actually ruled out the opening of the parliamentary term. Parliament ultimately decided to ignore this rule and began to debate the establishment of a regency .

The ruling party and the opposition agreed that the Prince of Wales should take over the reign. However, since the two parties had different understandings of the roles of parliament and monarchy, there was no agreement on the basis on which the reign should be instituted. For the ruling Tories party, a reign of the Prince of Wales also came with the risk of losing its influence.

Opposition leader Charles James Fox believed it was the heir to the throne's right to rule on behalf of his sick father. Prime Minister William Pitt argued that unless the monarch himself made arrangements for his representation, it was up to parliament alone to nominate a regent. He went even further and stated that, without the approval of Parliament, "the Prince of Wales is no more entitled to become head of state than any other citizen of the state". The Prince of Wales did not fully support Fox's views, although he was offended by Pitt's remarks. George's younger brother Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and Albany said the Prince of Wales would make no attempt to take power without Parliament's approval and condemned Pitt's proposal as "unconstitutional and illegal". According to Pitt's proposals, the powers of the future regent should be severely restricted. In his role as regent, the Prince of Wales should not be able to sell property of the king or give anyone a peer title . Only children of the king were exempt from this last rule. Prince George condemned Pitt's proposal, calling it a "project to create weakness, confusion and insecurity in every area of government," but Pitt was ultimately able to prevail.

The appointment of a regent was delayed even further, however, as the right of parliament to meet without the formal opening by the king was already being called into question. William Pitt proposed a legal device: by affixing the Great Seal of the Empire to a decree, the monarch could transfer many of his sovereign rights to a lord commissioner. Now the Lord Chancellor , the depositary of the Great Seal of the Empire , was supposed to affix the seal himself without the consent of the monarch. Although the act itself was unlawful and was sharply criticized by personalities such as Edmund Burke , the decree was valid because of the seal attached.

In February 1789, the House of Commons adopted the Regency Bill authorizing the Prince of Wales to reign as Prince Regent. But before the House of Lords could also pass the law, George III. recovered from his illness. The king subsequently recognized the legality of the procedure and took over the official business again.

Marriage to Caroline von Braunschweig

Despite the special payments from Parliament, the Prince of Wales' debts had grown to over half a million pounds by 1794. Should he marry, his debts would be settled and his pension would be increased to £ 100,000 at the same time. Caroline von Braunschweig was chosen as the future wife . Her father, Carl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , a favorite nephew of Frederick the Great , had distinguished himself as a general in the Seven Years' War . Caroline's mother was a sister of George III. Even if the Principality of Braunschweig was not large, it was allied with Prussia, which, like the United Kingdom, opposed the army of the French Republic .

On April 8, 1795, the wedding took place in St James's Palace . The bride and groom had only met for the first time three days earlier and had immediately developed antipathy for each other. Prince Georg simply left his bride standing shortly after the greeting and asked for a brandy . Caroline von Braunschweig, in turn, confessed to Lord Malmesbury , who had accompanied her on her trip from Braunschweig to Great Britain, that she found her stout future husband to be far less handsome in person than his portrait. Georg was already very drunk during the wedding and both spouses were averse from the start. According to his wife, Georg spent the wedding night in a state of intoxication under the fireplace screen. The marriage turned out to be a fiasco from the start. Georg found Caroline von Braunschweig unattractive and unsuitable in her unrestrained and often tactless behavior. In a letter he wrote to Lord Malmesbury a year later, he not only suspected that she had ceased to be a virgin on their wedding night, but also noted how repulsive he was about her lack of physical hygiene. He also stated that he only had sexual intercourse with his wife three times.

On January 7, 1796, almost exactly nine months after the wedding, Georg's only legitimate child, Princess Charlotte Augusta , was born. The couple tolerated each other during their pregnancy. Just a few months after the birth, Prince Georg was already considering separating from his wife and even questioned whether he was actually the father of his daughter. The antipathy towards his wife was reason enough for the prince's supporters to cut Caroline von Braunschweig at court to a large extent. Large parts of the British press, however, took the side of the princess, especially after it became known that Lady Frances Villiers - officially one of the princess's ladies-in-waiting and at that time mistress of the Prince of Wales - had taken letters from Caroline of Braunschweig and published their contents on Court had spread. Caroline von Braunschweig also met with sympathy from the British population. Attending the opera was one of the few occasions on which the Princess of Wales appeared in public. The audience welcomed her regularly with ovations, not least cheered on by press comments such as the Morning Herald: "[...] the country knows its worth, takes part in its difficulties and regrets what is being done to it." His wife's opinion of him was accordingly bad: "Mon père etait un héros, mon mari est un zéro." (My father was a hero, my husband is a zero).

Despite the attempts at reconciliation by George III, who expected his heir to the throne to have an exemplary married life, the couple separated in 1797. As early as the spring of 1796, Georg had informed his wife in writing of his intention to separate and stated that he would then waive the exercise of his marital rights , something should happen to his daughter, the future heir to the throne. Caroline von Braunschweig settled in the small country estate Montague House in the London suburb of Blackheath . Her daughter lived not far from her under the supervision of a governess, which made it possible for Caroline von Braunschweig to see her regularly.

In 1796 the Prince of Wales's financial problems were resolved, at least temporarily, by Parliament. Although Parliament refused to pay the entire debt, which now exceeds £ 600,000, it granted the Prince of Wales an additional annual contribution of £ 65,000. Another £ 60,000 was added in 1803 and the debt the Prince of Wales had accumulated by 1795 was paid off in 1806. However, the debts he had entered into after 1795 persisted.

"Delicate Investigation"

Shortly after the birth of his daughter Charlotte, the Prince of Wales made a will that made it clear that he still felt a connection with Maria Fitzherbert. She should be his main heir, while Caroline von Braunschweig, who was officially wedded to him , should inherit only one shilling . Despite this attachment to Maria Fitzherbert, the Prince of Wales had a number of sometimes long-lasting affairs. In addition to Lady Frances Jersey, whom he initially appointed as the lady-in-waiting of his official wife, his lovers included the well-known courtesan Grace Elliott and the Russian noblewoman Olga Scherebzowa. His later mistresses include Isabella Seymour-Conway, Marchioness of Hertford and, for the last ten years of his life, Elizabeth Conyngham, Countess of Conyngham .

The sexual freedoms that the Prince of Wales took out for himself, he did not apply to Caroline von Braunschweig. On her small country estate, she led a life free of courtly constraints and, by the standards of her time, unconventional. Their evening parties often lasted until the early hours of the morning. She was offended because she sometimes devoted herself to one of her guests for hours, often flirted openly with one of her male visitors, or received guests even when she was playing on the floor with her visiting daughter. Her guests included members of different social classes. A number of influential politicians and personalities at the court made it very important to keep in touch with her, as she might one day have considerable political influence as the mother of the future heir to the throne.

One of the characteristics of Caroline von Braunschweig was a great affection for children. She had eight or nine orphaned children raised in foster families at her own expense and took care of their upbringing personally. In November 1802, she finally adopted the then three-month-old baby William Austin. His parents were simple workers and had turned to the Princess of Wales, known for her charity, because their income was barely enough to raise their existing children. Unlike the other foster children, William Austin was housed directly in the Montague House and personally looked after by the princess. The sudden presence of an infant in the princess's house gave rise to rumors that she was the mother herself. At the urging of the Prince of Wales, King George III voted. In 1806, finally, the establishment of a secret four-person investigation commission, which was supposed to examine the way of life of Caroline von Braunschweig and which is called "Delicate Investigation". The composition of the commission was high-ranking; her membership included the Prime Minister. However, this commission, which neither heard the accused nor gave her the opportunity to object, was not covered by English law. The commission finally had to acquit Caroline von Braunschweig of the accusation of having given birth to a child out of wedlock, but criticized her way of life. Although details of the investigation were not disclosed, at least the findings leaked to the British press. To a large extent, this again took the side of the princess.

Regency

After the crisis of the reign of 1788/1789, the state of health of George III. stabilized to such an extent that he could go about his government business for the next two decades. It was not until October 1810, shortly after the fiftieth anniversary of his accession to the throne, that the disease broke out again seriously. One of his doctors compared the mental state of George III. with that of someone delirious. George III spent the rest of his life mentally deranged at Windsor Castle .

Parliament decided to proceed in a similar way to that in 1788. Without the consent of the king, the lord chancellor issued a decree with the great imperial seal, with which lord commissioners were appointed. They then gave their consent to the Regency Act 1811 on behalf of the king . The parliament curtailed some of the prince regent's rights. However, these restrictions ended one year after the law came into force.

Economic and domestic political environment

The economic and political environment during the Prince of Wales reign was difficult. Britain had suffered economic crises and multiple crop failures in the decade and a half since 1795. The wages of ordinary workers were so low that it was not enough to support a family. Working-class families therefore had to rely on their wives and children to work as well. It was not until 1819 that such laws prohibited children under the age of nine from being employed as workers. The members of traditional handicrafts tried to protect their livelihoods, and from 1811 to 1816 there was repeated organized destruction of machines and factories. The weavers organized the largest strike in 1813, when the abolition of the traditional seven-year apprenticeship became apparent. In the " year without a summer " 1816 there was another bad harvest and subsequent famine, which this time was exacerbated by the fact that the harvests were also poor in large parts of Europe, which made importing food more difficult or more expensive.

This crisis was considerably exacerbated because after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, armaments production and thus iron smelting , shipbuilding and coal mining declined considerably. At the same time, more than 300,000 British soldiers were released from active service and are now looking for work. Politically, since 1795, in response to the French Revolution and increasing radicalization within the British population, a number of civil rights had been restricted: Even speaking against the king or the constitution could be punished as high treason and gatherings of more than 50 people were prohibited if they have not been approved by the authorities beforehand. Nonetheless, radical propaganda writings flourished during this period, and for the first time newspapers were aimed specifically at workers. The Prince Regent was often the target of these writings. Newspaper editors Leigh and John Hunt responded with harsh words to the hymn of praise published by a pro-government newspaper on the occasion of the Prince of Wales' fiftieth birthday. For them was the prince

"[... a] broken word, a rascal in debt up to his ears and covered with shame, a despiser of marital ties, a companion of gamblers and demi-world figures, a man who has just completed half a century without the slightest claim to his gratitude To have earned the country or the respect of future generations. "

The Hunt brothers who had previously been due to his corpulence "Prince of Whales" the Prince of Wales - Prince of Whales - had mocked were sentenced to prison.

politics

The UK's Catholic minority was subject to a number of political restrictions. Among other things, they were not allowed to take seats in parliament. Whigs and Tories differed as to how far these restrictions should be lifted and Catholics should be given full civil rights. The Tories, led by Prime Minister Spencer Perceval , opposed widespread Catholic emancipation , while the Whigs supported it. The Prince Regent was also one of the opponents of Catholic emancipation. This attitude significantly influenced who he appointed to government over the next few years.

At the beginning of his reign, the Prince Regent initially announced that he would support William Grenville , the leader of the Whigs. However, he did not immediately appoint Lord Grenville Prime Minister. The Prince of Wales justified this with the fact that a sudden dismissal of the Tory government would damage the health of the king, who was a staunch supporter of the Tories, and thus destroy any chance of recovery. In 1812, when the king's recovery had become increasingly unlikely, the Prince Regent missed the opportunity to transfer government responsibility to the Whigs. Instead, he asked her to join the Spencer Perceval government. However, because of the fundamental differences of opinion on the question of Catholic emancipation, the Whigs refused to cooperate, whereupon the angry Prince Regent Spencer Perceval left in office.

On May 11, 1812, John Bellingham committed an assassination attempt on Spencer Perceval, who was killed in the process. The Prince Regent initially wanted to confirm the remaining members of the government under a new Prime Minister. But the House of Commons expressed the wish for a "strong and efficient government". The Prince Regent offered the office of Prime Minister Richard Wellesley and then Francis Rawdon . Both refused to form a coalition government as neither party was interested in power sharing at the time. The Prince Regent took the failed government formation as an opportunity to reappoint the Tory ministers of the Perceval government and transferred the office of Prime Minister to the Earl of Liverpool . He held this office until 1827.

Unlike the Whigs, the Tories were determined to continue the war against Napoleon Bonaparte . With the support of Russia , Prussia , Sweden , Austria and other countries, the French army was defeated in 1814. In the subsequent Congress of Vienna it was decided to elevate the Electorate of Hanover, ruled in personal union by the British monarch since 1714, to a kingdom. The Prince Regent had the interests of the House of Hanover represented separately by the Minister, Count zu Munster , who was particularly familiar to the royal family and who in this context successfully managed to enforce Hanover's independent negotiating position alongside that of the United Kingdom against Prussia. Finally, in 1815, the coalition wars ended with the Battle of Waterloo, which was victorious for the British . In the same year, the British-American War also ended without a real winner of these military conflicts being established.

Private environment

The Prince Regent did not allow the officially wedded wife Caroline von Braunschweig to play a role at his court. Their daughter, Charlotte Augusta , now a teenager, was under the supervision of their father, who had sole parental authority, and lived in the neighborhood of Carlton House. Mother and daughter were only allowed to see each other very rarely.

The increasingly isolated Caroline von Braunschweig turned to the king on January 13, 1813 in a letter drawn up by her legal advisor Henry Brougham , in which she pointed out, among other things, the injustice of the "Delicate Investigation" and demanded her rights as a mother. The Prince Regent left the letter unanswered, whereupon Henry Brougham passed the letter to the British press. Almost all the newspapers printed the letter in full. The Prince Regent reacted by leaking the charges of the "Delicate Investigation" to the press, and Henry Brougham countered by passing the documents on which Caroline von Braunschweig exonerated these charges to the press. The published material caused a sensation among the British public. Once again, large parts of the press and the public took the side of Caroline von Braunschweig. The reaction of Jane Austen , who wrote in a letter from a friend, is likely to be characteristic :

"Poor [Caroline von Braunschweig]. I will support her as long as I can because she is a woman and because I hate her husband - but I can hardly forgive her for describing herself as 'affectionate and affectionate' to this man she must despise - and the alleged relationship between her and Lady Oxford is, of course, bad. I don't know what to make of it. If I had to give up the [support of the] princess, I would be determined to argue that she would have behaved respectably if the prince had only treated her properly from the start. "

After assuring an annual allowance of 35,000 pounds, Caroline von Braunschweig decided to leave the United Kingdom and left on August 8, 1814 with a small entourage of her own choosing. In the following years the princess first traveled to the European continent and North Africa and then settled in Italy for some time.

Charlotte Augusta , the daughter of the Prince Regent couple, married Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg , who later became King of the Belgians , on May 2, 1816 . However, she died on November 6, 1817 as a result of a stillbirth. The Prince Regent was thus without an heir to the throne, unless he would father a legitimate child. Since this was not likely under the circumstances, one of his brothers would follow him. However, only the youngest brother was appropriately married and the ruling royal family lacked legal offspring. The death of the potential heir to the throne made the previously unmarried brothers of George look for suitable wives among the Protestant princesses of Europe. On July 13, 1818, the Duke of Clarence (and later William IV.) Married Adelheid von Sachsen-Meiningen and the Duke of Kent and Strathearn married Victoire von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld , the widowed Duchess of Leiningen , in a double wedding .

The Prince Regent's goal was still to divorce his wife. Members of the government were able to dissuade him from the high treason trial he was aiming for against Caroline von Braunschweig. According to English law, however, divorce could only be obtained if one of the two spouses was able to prove marital infidelity. With the support of the Prime Minister, the Prince Regent commissioned a well-funded commission of inquiry to collect compromising material about Caroline von Braunschweig. This investigative commission is also known as the "Milan Commission", since three of the commission members settled in Milan from September 1818 to hear witnesses there. Caroline von Braunschweig was not officially informed about the establishment of this commission of inquiry. She soon became aware of this, however, as the rumor quickly circulated that the commission members would financially reward testimony against her.

Royal rule

After the death of George III. on January 29, 1820, the Prince Regent succeeded him to the throne as George IV. This did not change much in the power structure of the United Kingdom. The influence of George IV on day-to-day politics remained minimal. At the time of his succession to the throne, George IV was obese and likely addicted to laudanum . During his time as Prince Regent, he had repeatedly suffered from illness. Because of the symptoms, his repeated illnesses are sometimes taken as evidence that he suffered from porphyria like his father , albeit obviously in a milder form.

Hearing on the "Pains and Penalties Bill"

Return of the Queen to England

George IV refused to recognize his official wife, Caroline of Braunschweig, as queen and ordered the British ambassadors to see other European monarchs do the same. By royal decree, Caroline's name was removed from the Church of England liturgy . Both measures met with little approval from the British public. As early as February 1, the Times demanded that the new queen be granted all rights to which she is entitled. George IV still wanted a divorce and he was ready to accept a change of government for it. But neither the Tories nor the Whigs found support for his project. In laborious meetings, his advisors succeeded in making it clear to George IV how problematic such a divorce process was for himself: A process would give Caroline von Braunschweig the opportunity to publicly discuss her husband's extramarital relations. Georg's already poor reputation would suffer even further through such a process. The king's advisors therefore tried to reach another agreement with Caroline von Braunschweig: In return for an increase in her annual allowance to 50,000 pounds , the now 52-year-old should assure her that she would stay away from the United Kingdom and waive her royal rights. Caroline von Braunschweig rejected these offers in part against the advice of her advisors. On June 5, 1820, she set foot on British soil again.

In parallel to the settlement offers made to Caroline von Braunschweig, George IV had a bill drawn up, the so-called Pains and Penalties Bill , which would authorize Parliament to approve the marriage between George IV and Caroline von Braunschweig without a trial and with a simple majority cancel if they come to the conclusion that the Queen's conduct is not worthy of her rank. The behavior of George IV would not be the subject of the investigation. The decision of the House of Lords and the House of Commons should be based on the results of the investigation by the Milan Commission. The Times heavily criticized the bill, pointing out that divorce law allows the separation of a man beyond reproach from his immoral wife. But it does not provide for the separation of two immoral people on the basis of the will of one of them. Just putting the marital behavior of one of the partners to the test would call marriage as an institution into question.

Hearing in front of the House of Lords

The hearing in the House of Lords began on August 17, 1820 . Large crowds gathered in the streets that led to Parliament. Lords like the war hero Duke of Wellington , who is actually revered by the British population, had to put up with whistles and boos on their way to the House of Lords because the assembled saw him as an opponent of the Queen. Caroline von Braunschweig, on the other hand, was greeted by the crowd with cheers and applause.

The hearing began with a discussion of the legality of the bill, while Caroline von Braunschweig's defense attorney, Henry Brougham, indicated that he would use every means to defend the queen. Many saw this suggestion as a threat that he had indubitable evidence of the marriage between Maria Fitzherbert and Georg IV. Maria Fitzherbert herself had probably left for Paris out of concern that she would be called to the stand . Two days later, the Crown Prosecutor Sir Robert Gifford delivered his speech to the assembled Lords, in which he accused Caroline of Braunschweig of continued adultery with her courier Baron Bartolomeo Pergami. As witnesses, the Crown Prosecutor interrogated a number of the Italian servants who had been employed by Caroline von Braunschweig over the next few weeks. The evidence they put forward for adultery was limited to circumstantial evidence: the two bedrooms were always close to each other, they often had breakfast together, the queen would have hooked on parchment when taking a walk, the parchment bed looked as if it hadn't slept in it; Suspicious stains had been found on the queen's bed sheet, and the queen had visited the sick Pergami twice in his bedroom. Only a few of the witnesses reported touching that suggested an intimate relationship between Caroline von Braunschweig and Pergami.

During cross-examination, the defense lawyers managed to question the witnesses' credibility. Some of the prosecution witnesses had to admit that they had benefited financially from working with the Milan Commission. With one of the main prosecution witnesses, Henry Brougham managed to demonstrate to the assembled House of Lords how well prepared it had been for the testimony. While Caroline von Braunschweig's former servant Theodore Majocchi had answered every question of the prosecution fluently, his answers to Henry Brougham's questions were much more hesitant. Theodore Majocchi answered more than 200 questions from Henry Brougham with a “Non mi ricordo” - “I can't remember”, which was a source of ridicule in the British press.

On November 10, 1820, the House of Lords approved the Pains and Penalties Bill with a slim majority of only 9 votes. This made it clear that this bill would not meet with approval in the House of Commons. Immediately after the vote was counted, Lord Liverpool announced that the government would withdraw the bill.

Effects

Through the process, George IV's standing among the people of the United Kingdom reached one of its low points. Caroline von Braunschweig's biographer Jane Robins came to the conclusion in her analysis of the hearing on the Pains and Penalties Bill that the United Kingdom was at the time on the verge of a revolution that could have led to the loss of the throne of George IV. Caroline von Braunschweig's legal advisor, Henry Brougham, claimed in his memoirs published decades later that he had unequivocal evidence of the marriage between the Prince of Wales and Maria Fitzherbert and that if the hearing turned out to be unfavorable for the queen, he would in fact have the right to the throne of George IV. questioned.

Before and during the hearing, the lower and lower middle classes in particular expressed solidarity with the Queen. “No Queen, no King” - “Without a queen, no king” was a threat that was often heard and even taken up by mutinous soldiers. The upper middle class and especially the upper class, on the other hand, kept their distance from the queen. According to Jane Robins, the Queen's guilt was secondary to the general public. For them, Caroline von Braunschweig was more of a symbolic figure of the opposition to George IV and the Tories he supported. The entire duration of the hearing was accompanied by demonstrations and marches, some of which also resulted in violent attacks on supporters of the king. The outcome of the hearing was celebrated euphorically in many cities in the United Kingdom, sometimes over several days. These celebrations were not free from excesses either. The expectation cherished by many that the Queen would become the figurehead of the opposition and reformist, however, was not fulfilled. Caroline von Braunschweig largely withdrew from the public eye in the months after the hearing and finally accepted the apanage offer of 50,000 pounds a year in March 1821.

The hearing is equally significant in the history of the British press. The British Times , which took the position of queen early on, attained the hegemony during this period that she would hold into the second half of the 20th century. Although the government taxed newspapers so highly that they became too expensive for the lower classes to purchase, reports of the hearing reached most of the UK's residents. Newspapers were displayed in pubs and coffee houses and were read and read out there. Many shared a subscription to a newspaper. A contemporary estimated that every single edition of the newspaper in London would be read by at least 30 people. It was the first event about which broad sections of the population formed a judgment based on the reporting.

Coronation, funeral of Carolines von Braunschweig

After what he saw as a failure of the hearing, George IV considered dissolving parliament, but rejected this idea because it posed the risk of continuing unrest. The appointment of a government led by Whigs politicians appeared to be an opportunity, at least for the first few days after the hearing ended, to divide the Queen's supporters. The majority of the Whigs, however, were supporters of Catholic emancipation, a reduction in the army and a cut in government spending. George IV was opposed to all three reform requests. In the end, George IV left Lord Liverpool in the office of Prime Minister.

The coronation of George IV took place due to the trial one year late on July 19, 1821 in Westminster Abbey without the Queen being allowed to attend. Caroline von Braunschweig was even refused entry to Westminster Abbey when she asked for it in the company of Lord Hood. George IV spared no expense with his extravagant taste. The total cost of the coronation ceremony was enormous: at £ 243,000 it exceeded the cost of George III's coronation. by more than 24 times. Half of them were paid out of French reparations payments based on the Second Peace of Paris . The new coronation crown of George IV was specially made for this and cost over £ 50,000. The £ 24,000 coronation regalia also proved to be particularly expensive ; Georg even sent tailors to Paris to copy Napoleon's coronation regalia. The regalia later found its way into Madame Tussaud's wax museum, but was rediscovered for the coronation of King George V in 1911 and has since been reused for all coronations. In the traditional coronation liturgy, the Archbishop of Canterbury , Charles Manners-Sutton, omitted the usual mentions of the Queen. The king suffered so much from the heavy regalia and the crown on the hot summer's day that he later said that he would not want to endure these hardships again for another kingdom.

The subsequent coronation banquet in Westminster Hall was held at 47 tables for 1,268 people, with galleries for an additional 2,934 spectators. The romantic taste of the time prompted the king to prescribe costumes for guests in the style of the Tudor and Stuart periods. The wax of the 3,000 candles dripped from the chandeliers onto the guests. After the king returned to Carlton House at 8:20 p.m., spectators from the galleries were also allowed to attend the buffets; This sometimes led to riots, soldiers barely prevented the storming of the kitchens, china and silver plates were stolen and Lord Gwydyr managed with difficulty to save the precious golden coronation service from the monarch's table. At 3 a.m. the last of the drunken guests were pulled out from under the tables. At the simultaneous folk festivals in town, a mob celebrating the Queen smashed window panes in the West End and had to be dispersed by the Household Cavalry . Georg's brother and successor Wilhelm IV later broke with the tradition of the coronation banquets, which goes back to the coronation of Richard the Lionheart in 1194, because he found it too expensive and time-consuming. The coronation banquet of George IV is so far the last to take place in Great Britain.

Caroline von Braunschweig died on August 7, 1821, just a few weeks after the coronation celebrations. It has repeatedly been speculated that she was poisoned. It is more likely, however, that she had stomach cancer . Caroline von Braunschweig had chosen Braunschweig as the place of her final resting place and during the transfer of the coffin to the coast there were again riots and demonstrations, as they had already accompanied the pains and penalties hearing. Prime Minister Liverpool had originally ruled that the funeral procession should only pass through the remote suburbs of London to avoid such unrest. However, the crowd waiting for the funeral procession to begin outside the Queen's house forced the guards accompanying the coffin to take a path through the City of London . Two people were killed and several injured in the clashes between the guards and the population.

An island in Antarctica discovered in 1821 was named Coronation Island in memory of the coronation .

Last years of rule

The highlights of the reign of George IV include his visit to Ireland in 1821 and especially his visit to Scotland in August 1822. The last British monarch to enter Ireland was Richard II and his stay in Scotland was the First visit by a British monarch to this part of the country since Charles II in 1650. In 1821 Georg was also the first monarch in 66 years to visit Hanover and its German homeland and was enthusiastically celebrated there.

Walter Scott was instrumental in organizing the 21-day visit to Scotland and used the opportunity to present Scottish traditions and way of life at several of the lavish celebrations. George IV reciprocated by appearing several times in a kilt , thereby helping to make this traditional highland garb so popular that it became the national costume of all of Scotland during the 19th century and also in the more English-influenced ones Lowlands was worn. In Edinburgh , the King gave a reception at Holyrood Palace and ordered its renovation, which extended over the next ten years, leaving the rooms of Mary Queen of Scots unchanged.

The trip to Scotland was the last great trip that George IV made. He then increasingly withdrew to Windsor Castle. His excessive lifestyle had made him so bulky that he was increasingly the target of ridicule when he appeared in public.

He rarely interfered in day-to-day politics, and occasionally with contradicting views. When the question of Catholic emancipation was on the agenda again in 1824 , George IV initially expressed himself in public as emphatically anti-Catholic. His position was shared by Prime Minister Liverpool, so that legal and political equality of the Catholic citizens of the United Kingdom seemed unenforceable for a long time. However, Lord Liverpool resigned in April 1827 and was replaced by the Tory George Canning , who was a proponent of Catholic emancipation. George IV used the inauguration of George Canning as an opportunity to publicly declare that his anti-Catholic attitude resulted only from the veneration of his father, who had very strict views on this point. George Canning died just five months later without any reform steps being taken. The new Prime Minister was Viscount Goderich , who continued the shaky coalition government until January 1828. His successor in office was the Duke of Wellington , who was originally a staunch opponent of Catholic emancipation. In the meantime, however, the Duke had come to the conclusion that further discrimination against Catholics was no longer politically tenable. With a lot of persuasion, the Duke succeeded on January 29, 1829 in getting the King's approval of the Equal Opportunities Act. However, under the influence of his fanatically anti-Catholic brother, the Duke of Cumberland, the king revoked his consent a little later, whereupon all cabinet members submitted their resignation on March 4th. George IV came under such political pressure that he ultimately had to agree to the Equal Opportunities Act.

George IV died on June 26, 1830 and was buried on July 15 in St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle . The eldest of his brothers, Friedrich August , died childless on January 5, 1827. Heir to the throne was therefore the next younger William, Duke of Clarence .

Contemporary reception

William Thackeray wrote of the vain George IV, who liked to be called the "leading gentleman of Europe" :

“I look back on his life and remember only a bow and a grin. I try to remember details and see silk stockings, padding, starch, a coat with frogs and a fur collar, a star and a blue ribbon, an incredibly perfumed handkerchief, one of Truefitt's best nut brown wigs - heavily pomadized - a set of teeth and a big black stick, an under-vest, even more under-vests and then - nothing. "

The Duke of Wellington described George IV during the political crisis of 1829 as selfish, ill-tempered, wrong and devoid of any positive qualities. Years later, his verdict was far milder. Among the positive characteristics of George IV, Wellington counted among other things his committed promotion of the fine arts and the unusual and sometimes contradicting mixture of talent, wit, folly, stubbornness and good-heartedness that had distinguished George IV.

The rule of George, which was characterized by eccentricity and extravagance, led to a low point in the reputation of the monarchy, which only found stronger support among the population again under his niece Victoria . On the occasion of his death, the Times wrote of George IV:

“[…] Never has a man been mourned less by his fellow men than this late king. What eyes cried for him? What heart sighed in selfless grief for him? [...] if he even had a friend, a devoted friend from whatever class, then we assure us that we never heard his name. "

legacy

Regency art epoch

Even if Georg's political record was modest, he made a significant contribution to promoting the visual arts. The reign of George lends its name to the Regency art epoch , the beginning of which is dated today when the Prince of Wales moved into Carlton House in 1783. He had the house rebuilt from 1783 to 1796 by the architect Henry Holland and employed French interior decorators and craftsmen. The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 led to the sale of many Hôtels particuliers in Paris , as a result of which confiscated furniture and works of art from the 17th and 18th centuries came on the market there on a large scale. George IV sent agents to Paris and had large quantities of furniture, tapestries, paintings and porcelain bought up, including a valuable Sèvres service by Louis XVI.

After the death of his father in 1820, he initially planned to expand Carlton House because the official residence, St James's Palace from the Renaissance period, was felt to be out of date. His parents had bought Buckingham House as a private residence in 1761 , where all his siblings were born. Since the manor house had a large park and plenty of space for other new buildings, George IV then decided to expand it into a royal palace and thus created Buckingham Palace from 1826 . The architect John Nash extended the small house laterally and towards the park and added large side wings. The Marble Arch, a colossal triumphal arch , stood at the point where today's front facade was built . The new palace was designed in the French classical style and George IV had it furnished with French furniture from Carlton House, which he had demolished in 1825. Sir Charles Long advised him on the glamorous interior design, for which he acquired additional furniture and art objects. When he died, the building was not quite finished. The escalating costs caused concern in parliament and in the press. He also had the Royal Apartments at Windsor Castle magnificently redesigned and furnished; there he spent the last year and a half of his life.

Before the beginning of his reign, the prince had already been the builder of several new and style-defining buildings and repeatedly commissioned renovations to the palaces he lived in. His construction activities were one of the reasons for his persistently high debt. The then Prince of Wales spent over 54,000 pounds just to build the palatial stable for his horses in Brighton , in which forty-four horse stalls are grouped in a ring around a fountain, which in turn was crowned by a dome. The Royal Pavilion in the up-and-coming seaside resort of Brighton is probably the building that is most associated with it next to Buckingham Palace. The palace, which was completed by John Nash during the reign, is externally based on the architecture of the Mughal Empire . With its predominantly Chinese-inspired interior design, it was considered one of the most exotic palaces in Europe. Among the special features of the palace, some of which were admired by numerous visitors and partly smiled at because of its luxurious opulence, was the tent-shaped ceiling of the banquet hall, in the middle of which a large silver dragon held a huge gas lamp. John Nash also designed Regent's Park , Regent Street and Trafalgar Square , all of which were initiated by George IV.

Fashion

One of the prince regent's confidants was “Beau” Brummell , who is still considered the prototype of the dandy today. Under his influence a very luxurious and colorful men's fashion developed. A well-dressed man of the Regency period changed his clothes several times a day and chose the form in which he wore his scarf with the utmost care. The historian Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson described the years influenced by George IV as the "final parade of the peacocks before the beginning of the sadness of the Victorian era, in which the wearing of lively colors was reserved for the military".

George IV, however, favored darker colors with increasing age, as these better covered his body. He also preferred the looser-fitting and therefore more advantageous long trousers over the knee trousers that had been customary at court until then. His willingness to follow Beau Brummel's scarf fashions is also attributed to the fact that they helped him hide his double chin. The fashion innovations that George IV made popular during his time as crown prince also included the renouncement of wearing powdered wigs.

Popular culture

To this day there are numerous monuments in Great Britain that commemorate George IV. Most were built during his reign. The best known are the equestrian statues in London's Trafalgar Square , in Windsor Park and in front of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. In Edinburgh , the George IV Bridge, designed by the architect Thomas Hamilton and completed in 1835, commemorates his visit to Scotland.

In novels, television series and films, George IV is usually portrayed as extravagant, dull and irresponsible. The best-known examples are the portrayals of himself by Hugh Laurie in the comedy series Blackadder , by Peter Ustinov in the 1954 film Beau Brummell and by Rupert Everett in the 1994 film The Madness of King George . In contrast, the BBC series “ The Prince Regent “From 1979 a more differentiated picture of the Prince of Wales and thus corresponds more to the later judgment of the Duke of Wellington mentioned above, in that he was extremely art-minded, gifted, full of wit and irony, loving and kind-hearted towards his neighbors, but also stubborn and can be easily influenced. The fantasy novel Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke is set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars and the reign of George IV, whereby his lifestyle is also caricatured here.

Pedigree

| Pedigree of King George IV. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great-great-grandparents |

|

Margrave |

Duke |

Prince |

Duke |

Count |

Duke |

Count |

| Great grandparents |

|

Duke |

Duke |

Duke |

||||

| Grandparents |

|

Duke Karl of Mecklenburg (1708–1752) |

||||||

| parents |

|

|||||||

See also

literature

- Jeremy Black: The Hanoverians. The History of a Dynasty. Hambledon Continuum, London 2004.

- Saul David: Prince of Pleasure: The Prince of Wales and the Making of the Regency . Grove Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8021-3703-2 .

- Michael De-la-Noy: George IV . Sutton Publishing, Stroud, Gloucestershire 1998, ISBN 0-7509-1821-7 .

- John W. Derry: The Regency Crisis and the Whigs . Cambridge University Press, 1963.

- Christopher Hibbert: George IV, Prince of Wales, 1762-1811 . Longman, London 1972, ISBN 0-582-12675-4 .

- Christopher Hibbert: George IV, Regent and King, 1811-1830 . Allen Lane, London 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0487-9 .

- Michael Maurer: Little History of England , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-009616-2

- Steven Parissien: George IV - Inspiration of the Regency . St. Martin's Press, New York City 2002, ISBN 0-312-28402-0

- Joachim Peters: Georg IV .. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 33, Bautz, Nordhausen 2012, ISBN 978-3-88309-690-2 , Sp. 509-512.

- Jane Robins: Rebel Queen - How the Trial of Caroline Brought England to the Brink of Revolution , Pocket Books, London 2007, ISBN 0-7434-7826-6

- John Röhl, Martin Warren, David Hunt: Purple Secret - Genes, 'Madness' and the Royal Houses of Europe , Bantam Press, London 1999, ISBN 0-552-14550-5

- Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson: Blood Royal - The illustrious house of Hanover , Ebenezer Baylis & Sons, London 1979, ISBN 0-224-01477-3

- EA Smith: George IV (The English Monarchs Series) . Yale University Press, New Haven 1999, ISBN 0-300-07685-1

- Hermann Schuhrk: King George IV's visit to Pattensen on October 29, 1821. Association for the promotion of the town history of Springe eV, Springe 2014, pp. 98-108.

- Adolf Schaumann : Georg IV. In: General German Biography (ADB). Volume 8, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1878, pp. 651-657.

- Edgar Kalthoff: Georg IV .. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 6, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1964, ISBN 3-428-00187-7 , p. 213 f. ( Digitized version ).

Web links

- Literature about George IV in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about George IV in the German Digital Library

- Entry in the Classic Encyclopedia ( Memento from July 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

Single receipts

- ↑ Ida Macalpine, Richard Hunter: The 'insanity' of King George III: a classic case of porphyria . In: Brit. Med. J. Band 1 , 1966, p. 65-71 .

- ↑ Röhl et al., Pp. 69-102.

- ↑ Paris, p. 171.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 2.

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Prince of Wales 1762-1811 , p. 2.

- ↑ a b Robins, p. 12.

- ↑ quoted from Gristwood, p. 134.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 48.

- ↑ Gristwood, pp. 114, 131-147 and 246.

- ^ EA Smith, pp. 25-28.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 33.

- ↑ I. Naamani Tarkow: The Significance of the Act of Settlement in the evolution of English Democracy . In: Political Science Quarterly . tape 58 , no. 4 , December 1943, p. 537-561 .

- ^ A b Philip Smith: A Smaller History of England, from the Earliest Times to the Year 1862 . Harper & Bros., 1868, pp. 295 .

- ↑ EA Smith, pp. 36-38.

- ↑ David, pp. 57-91.

- ^ A b Arthur Donald Innes: A History of England and the British Empire, Vol. 3 . The MacMillan Company, 1914, pp. 396-397 .

- ↑ De-la-Noy, p. 31.

- ↑ Ida Macalpine, Richard Hunter: The 'insanity' of King George III: a classic case of porphyria . In: Brit. Med. J. Band 1 , 1966, p. 69-102 .

- ↑ Michael Maurer: Little History of England, Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-009616-2 , p. 311.

- ↑ David, pp 92-119.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 54.

- ↑ Derry, p. 71.

- ↑ Derry, p. 91

- ↑ Thomas Erskine May : The Constitutional History of England Since the Accession of George the Third, 1760-1860 . 11th edition. Longmans, Green & Co, London 1896, pp. 184-195 .

- ^ Robins, p. 15.

- ^ Robins, p. 5.

- ↑ Robins, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Marita A. Panzer: England's Queens. From the Tudors to the Windsors , Munich 2003, p. 203.

- ↑ Robins, p. 17 f.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 19-21.

- ↑ Robert Nöll von der Nahmer: Bismarck's Reptilienfonds. Mainz 1968, p. 29.

- ^ Robins, p. 22.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 97.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 92.

- ↑ Robins, p. 20.

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Prince of Wales 1762-1811 , p. 18.

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Regent and King 1811-1830 , p. 214.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 27-30.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 30-33.

- ^ Sinclair-Stevenson, p. 150.

- ↑ Arthur Donald Innes: A History of England and the British Empire, Vol. 4 . The MacMillan Company, 1915, pp. 50 .

- ↑ Maurer, pp. 313–339.

- ^ Sinclair-Stephenson, p. 155 and Robins, p. 39.

- ↑ Robins, p. 39.

- ↑ Maurer, p. 342

- ^ EA Smith, p. 146.

- ↑ Paris, p. 185.

- ^ EA Smith, pp. 141-142.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 144.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 145.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 40-43.

- ↑ Robins, p. 42.

- ↑ Robins, p. 49.

- ^ Panzer, p. 219.

- ^ Robins, pp. 76 and 77.

- ↑ Arthur Donald Innes: A History of England and the British Empire, Vol. 4 . The MacMillan Company, 1915, pp. 81 .

- ↑ Röhl et al., Pp. 103-116.

- ^ Robins, p. 97.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 98-117.

- ^ Robins, p. 143.

- ^ Robins, p. 169.

- ↑ Robins, p. 172 f.

- ↑ For a detailed description of the hearing before Parliament, see Robins, pp. 187–287.

- ↑ Robins, p. 286 f.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 235-246.

- ^ Robins, p. 288.

- ^ Robins, p. 136.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 126-127; P. 246.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 202-203; Pp. 235-236, 237-238 and 263-265.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 289-306.

- ^ Robins, p. 243.

- ↑ Robins, p. 304 f.

- ↑ Robins, pp. 308-311.

- ^ A b Arthur Donald Innes: A History of England and the British Empire, Vol. 4 . The MacMillan Company, 1915, pp. 82 .

- ^ Robins, p. 311.

- ^ Sir Roy Strong: Coronation: A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy , London 2005, p. 394

- ↑ George IV's Coronation on brightonmuseums.org.uk

- ↑ Lucinda Gosling, Royal Coronations (2013), p. 54

- ↑ See also the English article Coronation of George IV

- ^ Strong, p. 414

- ^ Robert Huish, An Authentic History of the Coronation of George IV. , London 1821, pp. 283-284

- ^ Robins, p. 313

- ↑ De-la-Noy, p. 95.

- ↑ Paris, pp. 324–326

- ↑ A detailed description of the visit to Scotland can be found in Sinclair-Stevenson, pp. 157–173.

- ^ The official website of the British Monarchy. Retrieved February 12, 2007 .

- ↑ Paris, p. 355.

- ↑ Paris, p. 189

- ^ EA Smith, p. 238.

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Regent and King 1811-1830 , p. 292.

- ↑ Paris, p. 190.

- ^ EA Smith, p. 237.

- ↑ Paris, p. 381.

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Regent and King 1811-1830 , p. 336.

- ^ Sinclair-Stevenson, p. 155.

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Regent and King 1811-1830 , p. 310

- ↑ Hibbert: George IV: Regent and King 1811-1830 , p. 344.

- ↑ The Times, July 15, 1830, quoted in Hibbert: George IV: Regent and King 1811-1830 , p. 342.

- ↑ George IV and French furniture , on the Royal Collection website

- ↑ Furnishing Windsor Castle - George IV's lavish refurbishment , Royal Collection

- ^ Sinclair-Stevenson, p. 194.

- ↑ Jessica MF Rutherford: The Royal Pavilion: The Palace of George IV . Brighton Borough Council, 1995, p. 81, ISBN 0-948723-21-1 .

- ^ Sinclair-Stevenson, p. 197.

- ^ Sinclair-Stevenson, p. 178.

- ↑ a b Paris, p. 114.

- ↑ Paris, p. 112.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| George III |

King of the United Kingdom 1820–1830 |

William IV |

| George III |

King of Hanover 1820–1830 |

William IV |

| George III |

Prince of Wales 1762-1820 |

Prince Albert, later King Edward VII. |

| Friedrich Ludwig of Hanover |

Duke of Cornwall Duke of Rothesay 1762-1820 |

Prince Albert, later King Edward VII. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | George IV |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Georg August Friedrich; George Augustus Frederick |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of Great Britain, Ireland and Hanover (1820–1830) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 12, 1762 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | St James's Palace |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 26, 1830 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Windsor Castle |