Sentinelese

The Sentinelese (also known as Sentineli ) are an indigenous people isolated from the outside world on North Sentinel Island , an Andaman island in the Bay of Bengal that is administered by India as part of the Andaman and Nicobar Union Territory . They live as hunters and gatherers on the 12 × 10 km island (60 km² ), which is almost completely covered by tropical jungle . The 2011 census in India gives the number of their dependents at 15, 12 men and 3 women. It is estimated, however, that between 100 and 150 Sentinelese could live on the island. 39 relatives were given for 2001 and a total of 24 for 1991; In 1911 the number of 117 Sentinelese was determined.

The Sentinelese are recognized by the Indian central government as a “ registered tribal community ” and as a “ particularly endangered tribal group ”. Both administrative divisions grant special state property rights. Because the Sentinelese have long refused to contact strangers, even by military means, the government has banned any attempt at contact with them and set up a restricted zone of three kilometers around the island ( see below ).

The ethnologist Vishvajit Pandya of the University of Delhi pointed out that the Sentinelese have long had an idea of the outside world, since the Bay of Bengal is a trade route that has been used for centuries. There can therefore be no question of “untouched” with them.

| Sentinelese | |

|---|---|

| year | number |

| 2011 | 15th |

| 2001 | 39 |

| 1991 | 24 |

| 1981 | 100 |

| 1971 | 82 |

| 1961 | 50 |

| 1931 | 50 |

| 1921 | 117 |

| 1911 | 117 |

classification

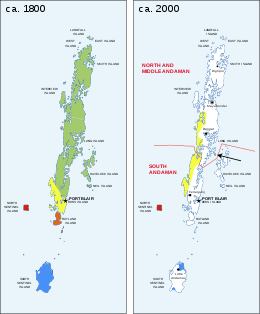

left around 1800 - right around 2000

Sentinelese (their island territory is still untouched - estimated 39 members in 2001) Greater Andaman (around 1800 a total of 10 groups - 43 members in 2001) Jarawa (240 members in 2001 ) Onge (96 members 2001) Jangi (extinct in the 1920s) non-indigenous / uninhabited area Already in 1789–1793 there had been a sharp decline in population on the original homeland of the Jarawa; after the 2004 tsunami , the Onge and Greater Andaman people withdrew to isolated settlements; the Jarawa have changed their settlements and occupy the former homeland of the Great Andaman people

According to their physical characteristics, the Sentinelese are assigned to the Negritos , a collective term for several small and curly-haired ethnic groups who mostly live in remote regions of the Malay island world . Video recordings from 1991, however, show “quite contrary to all [sic!] Negrito expectations, quite large and muscular […] adults and children”.

The island was believed to have been settled from South Andaman Island . The Jarawa living there , with whom the Sentinelese seem to be more closely related than with other Negritos, conquered the approximately 35 kilometers to the nearest coast at what is now Port Muat, probably with bamboo rafts or outrigger canoes .

The language of the Sentinelese has not been explored. It is assigned to the Andaman languages for geographical reasons alone . The well-known languages of the closest neighboring peoples, such as the Onge living on Little Andaman or the Jarawa, are related to one another. With the Sentinel language, these apparently do not share a sufficiently common vocabulary to serve as a link. Onges brought to the island in the 1980s could not understand the Sentinelese language.

The Sentinelese are the last isolated indigenous people in the Andaman Islands after the neighboring Jarawa had contact with Indian settlers since 1998.

There is, in connection with the study of the language, genetic evidence that the Andamans may be descendants of the first wave of emigration from Africa around 100,000 years ago. How far these findings also apply to the Sentinelese is unclear.

Way of life

The Sentinelese are one of the last ethnic groups in the world to live outside of industrialized civilization (compare indigenous people ). Because of their remoteness, very little is known about them and can only be inferred from a few observations and encounters. Reports do not mention any clothing, the people being observed are often described as naked, sometimes with a decorative cord around the waist. If weapons were sighted, then only "homemade" ones made from local materials - the metal tips of their arrows and throwing lances are a specialty. It is believed that the islanders were able to extract foreign materials from the wrecks of several stranded ships. The shipwrecks of the merchant ship Nineveh 1867, the Portuguese Navy's landing ship 532 in 1970, the Rusley in 1977 and the freighter Primrose in 1981 are documented.

Ethnologists ( anthropologists ) described the Sentinelese as “ hunters and gatherers ” (hunters) early on and have repeatedly found confirmation of this classification.

Settlements

There is no evidence for the construction of permanent housing; it is believed that the Sentinelese sleep in short-lived shelters. During two expeditions, simple sleeping quarters with inclined wickerwork of palm branches and hearths surrounded by stones were found. It has often been observed that they use fire - it is not known whether they have a fire-making technique or are forced to keep fireplaces in operation permanently. The storage of embers in a tree hollow was observed.

Sentinelese use natural materials that they find on the island, but also objects and materials that are washed up as flotsam . The first expedition in 1879 picked up and took away a number of items that are now in the British Museum in London, including a woven basket and a wooden lance with an iron tip.

Food bases

The Anthropological Survey of India (AnSI), a department of the Indian Ministry of Culture, named the islanders' nutritional requirements in 2017:

- Coconuts, roots, tubers, various leaves and probably plantains

- a species of wild boar, honey, turtles and their eggs, as well as various species of fish and other aquatic animals, both from lagoons in the interior of the island and from the coastal areas

Boat building

The islanders make einbaumartige canoes wooden ago whose propulsion on poking rods occurs. This allows them to move on the lagoons and along the coastline, but not navigate deeper waters; especially since the sea is very rough during the six-month monsoon season . They were observed more often during trips between the coral reefs close to the shore. The shallow reefs that surround the island attract many fish and can create subdivisions where marine animals can get entangled. During the 2004 earthquake in the Indian Ocean and the subsequent tsunami , the tectonic plate under the island was raised by one to two meters, widening its coastline and drying some of the coral beds.

Threats

Poachers are increasingly exploiting the fishing grounds around the Andaman Islands, which endangers the food sources of the Sentinelese. Neighboring indigenous peoples like the Jarawa, who have contact with outsiders, repeatedly complain about poaching and its effects on their food sources.

It is assumed that this group is genetically extremely homogeneous, that is, genetically very poor, due to the centuries, perhaps even millennia of isolation on a small island. For many generations there may have been only descendants from connections between more or less related individuals. There was probably no gene inflow from outside because of the isolation. Therefore, population genetic phenomena such as genetic drift , founder effects or genetic bottlenecks have certainly occurred on the island in the past . Recessive hereditary diseases are also likely to occur frequently in sentineles , as the likelihood of homozygosity due to the marriage of relatives is high.

The transmission of diseases when contact is made, the pathogens of which may be unnoticed or harmless to the carrier itself, represents a serious threat to the Sentinelese, who, due to their isolation, live in isolation from many infectious diseases and are unlikely to have developed a specific immune response. Other indigenous peoples in the Andaman Islands were almost completely wiped out by violence and disease after contact. The Indian government recognizes the right to autonomy among the Sentinelese and has therefore declared the island and the surrounding waters within a three-kilometer radius to be a prohibited zone and forbidden contact with them.

Contact with outsiders

In the past there have been repeated attempts to contact the Sentinelese in order to research them. Some of them were abducted. The Sentinelese responded by retreating into the forest or attacking the intruders with a bow and arrow. Since they are massively defending themselves against any kind of rapprochement, the Indian government temporarily stopped attempting to contact them in 1996. Scientists who were involved in contact attempts reported clear threatening behavior, the sole purpose of which was to keep intruders away from the island.

Around 1296, the Venetian trader Marco Polo first described the inhabitants of the Andaman Islands - very probably only by hearsay: They are the wildest and most dangerous human race, equipped with the eyes, ears and teeth of dogs.

In 1771 the crew of the Diligent , a survey ship of the British East India Company sailing past the coast of North Sentinel Island , saw the glow of several fireplaces in one night. This is considered to be the first testimony for people living on the island; there was no shore leave.

From 1800

In 1867 the Indian merchant ship Nineveh ran aground on a coral reef off North Sentinel Island. The crew and passengers escaped to the beach in the dinghy. On the third morning the camp was attacked by several dark-skinned, naked men, shouting at battle, with arrows whose tips appeared to be made of iron. The castaways were able to defend themselves with sticks and stones. All survived and were picked up a few days later by a British Navy lifeboat. This was the first sighting of people who have since been referred to as "Sentinelese" after the island's name. The British administrator Homfray then tried to pay a visit to the island. The abandoned wreck of the Nineveh provided the Sentinelese with materials such as metal; presumably the arrowheads of the warriors came from an earlier shipwreck or beach debris washed ashore.

In 1879 the British administrator of the Andaman Islands, Maurice Vidal Portman , was the first European to set foot on the island. With a large troop of armed men and trackers from other Andaman tribes, he roamed the island for days in search of the inhabitants that Portman had a personal interest in exploring. The troops found simple palm twig huts and campfire sites and eventually came across an old couple with four children. They were abducted for investigation in the capital Port Blair on South Andaman Island , 60 km away .

Portman later wrote regretfully that the group "got sick quickly and the old man and his wife died, so that the four children were sent home with many presents." Portman noted "their peculiar idiotic expressions of face and behavior." The further consequences of this incident are unclear. It is conceivable that the children who returned home infected more Sentinelese, with devastating consequences for the tribe. Such a catastrophe could be a plausible explanation for the hostility towards the outside world.

Portman made several unsuccessful attempts to contact the Sentinelese until 1896, studied the languages of the other indigenous island peoples and put on a first ethnographic collection. He later stated in a speech to the Royal Geographical Society in London about his research among the Andaman Indians:

“Their association with outsiders has brought them nothing but harm, and it is a matter of great regret to me that such a pleasant race are so rapidly becoming extinct. We could better spare many another. "

“Their connections with outsiders have brought them nothing but calamity, and it is a matter of great regret for me that such a pleasant race is being so quickly extinguished. We should rather spare the many others. "

In 1896 a Hindu convict escaped from the prison camp on the Great Andaman Islands with a self-made raft and drifted to North Sentinel Island. There persecutors found his body with multiple arrow wounds and a slit throat; Locals were not observed.

From 1900

In 1903 the British administrator Gilbert Rogers paid a visit to the island.

In 1911 the British colonial official MCC Bonington landed with some companions on the west coast of the island and was not attacked. According to Bonington, eight men fled into the jungle and two took off in canoes. The British walked a few kilometers inland, where they found some housing but met no resistance. Bonington believed that gifts could "tame" the Sentinelese.

In 1926 the British administrator Bonington visited the island.

In 1970 the Indian government sent a land surveying team to erect a stone tablet on the island, the inscription of which declares the island to be part of India.

In 1974 a National Geographic film crew made some footage of Sentinelese for the documentary Man in Search of Man . The group ended up with some ethnologists, armed police officers and the Indian photographer Raghubir Singh , who took sensational pictures. In the same year, the Austrian explorer Heinrich Harrer filmed the island from afar on his Andaman expedition.

After 1974 some film and photo recordings were made during later expeditions of the Indian government. The Sentinelese were always left with gifts.

In 1981 the freighter Primrose ran aground on a coral reef a few hundred meters from the island. Because of the strong waves, the sailors could not lower their dinghy into the water. They watched as several Sentinelese gathered on the beach, threateningly brandished their weapons, and began to prepare boats. The persistently stormy weather prevented the Sentinelese from approaching and their arrows did not reach the ship. A few days later the Indian Navy reached the ship and the crew was rescued. Because of the aggressiveness of the Sentinelese, the Primrose was not recovered and lay in front of the island.

1991 saw the first friendly contact between a group of Indian government officials and some Sentinelese, where they accepted sacks of coconuts as gifts. The two ethnologists Trilokinath Pandit and Vishvajit Pandya were involved, as well as the anthropologist Madhumala Chattopadhyay as the first woman .

After 1996 the government's advances were temporarily suspended. Between 1967 and 1994 the political line of the central government had been under the motto “Mission of good intentions”, now it was “hands off, keep an eye”. Since then, the island has been a " Tribal Reserve Area", a military restricted area , surrounded by a three-kilometer protection zone. Ships and helicopters of the Indian Navy patrol regularly, mainly because of foreign fishermen, smugglers, poachers and pirates.

From 2000

In 2004, three days after the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami , a helicopter flew over the island in search of survivors. He was shot at with arrows.

In 2005 the government made another attempt at contact.

In 2006, two fishermen were believed to have been killed by the Sentinelese after their boat drifted onto the island. The exact circumstances of death are unclear, as is the question of whether the fishermen rowed to the coast in secret and without permission or accidentally deviated from their course. The islanders buried the bodies in the sand, and subsequent tidal waves uncovered the graves. The sighting of the bodies on January 28, 2006 by a search helicopter provided no evidence of rumors that the Sentinelese were practicing cannibalism .

In 2014, the government made another attempt at contact, and sixteen people were found: seven men, six women and three children.

2018, the Americans tried John Allen Chau to arrive despite the known contact him ban the Indian government on the island and the locals proselytize . He was killed by islanders. The US did not ask the Indian government to take legal action against the killing.

See also

- indigenous peoples of Asia (list)

literature

- 2018: Kavita Arora: Indigenous Forest Management In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India . Springer, Cham 2018, ISBN 978-3-03000033-2 .

- 2000: Adam Goodheart: The Last Island of the Savages. In: The American Scholar. Volume 69, No. 4, December 5, 2000, pp. 13-44 ( online at theamericanscholar.org).

- 1977: Heinrich Harrer : The Last Five Hundred. Expedition to the dwarf peoples on the Andamans. Ullstein, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-550-06574-4 .

- 2009: Vishvajit Pandya : The Specter of 'Hostility': The Sentinelese between Text and Image. In: The same: In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858-2006). University Press of America, Lanham MD 2009, ISBN 978-0-7618-4153-1 , pp 326-364 (English; Extract in the Google Book Search).

- 1962: SS Sarkar: The Jarawa of the Andaman Islands. In: Anthropos. Volume 57, Issue 3./6. Friborg 1962, pp. 670-677 (English; ISSN 0003-5572 ).

- 1976: Raghubir Singh : The struggle for survival. In: Geo. Hamburg 1976, pp. 8-24 ( ISSN 0342-8311 ).

- 1975: Raghubir Singh: The Last Andaman Islanders. In: National Geographic Magazine. Volume 148, No. 1. Washington DC 1975, pp. 32-37 (English; ISSN 0027-9358 ).

- 2010: UNESCO , Pankaj Sekhsaria, Vishvajit Pandya (ed.): The Jarwaw Tribal Reserve Dossier. Cultural & biological diversities in the Andaman Islands. UNESCO, Paris 2010 (English; PDF: 12 MB, 220 pages on unesco.org).

Documentation

- 2019: ZDF editorial team Terra X : North Sentinel Island: Entry prohibited! on YouTube, June 16, 2019, accessed on June 17, 2019 (17 minutes; with rare film recordings and interviews by Indian ethnologists).

Web links

- Survival International : The Sentinelese (portal page).

- Carola Krebs in conversation with Dörte Hinrichs: Sentinelese kill missionary: “We have no right to penetrate their home”. In: Deutschlandfunk . November 29, 2018 (Krebs is an ethnologist ).

- Madhusree Mukerjee: North Sentinel Island: Civilization kills almost everyone on whose shores it lands. In: Spektrum.de . November 29, 2018 ( Scientific American Editor ).

- Alard von Kittlitz: The Sentinelese - the most isolated people in the world: "You can't pretend they don't exist". (No longer available online.) In: Faz.net . February 9, 2010, archived from the original on February 4, 2012 (interview with Vishvajit Pandya).

- Vinay K. Srivastava: The Sentinelese (PDF: 1.5 MB, 16 pages). National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST), New Delhi 2017 (English; Powerpoint presentation by a professor from the Anthropological Survey of India at the PVTGs seminar Conservation of Particularly Vulnerable Tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands ).

- Press review: should indigenous peoples remain isolated? In: eurotopics . Federal Agency for Political Education .

Remarks

- ↑ In the original: “administrator”

- ↑ In the original: "[...] their 'peculiarly idiotic expression of countenance, and manner of behaving'."

Individual evidence

- ^ Ministry of Tribal Affairs: Report of the High Level Committee on Socio-Economic, Health and Educational Status of Tribal Communities Of India. Government of India, New Delhi May 2014, p. 95 (English) indiaenvironmentportal.org.in (PDF; 5.0 MB, 431 pages)

- ↑ a b c Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Statistics Division: Statistical Profile of Scheduled Tribes in India 2013. Government of India, New Delhi 2013 (English) tribal.nic.in (PDF; 18.1 MB; 448 pages)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Vinay K. Srivastava: The Sentinelese. (PDF) National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST), New Delhi 2017 (English; PDF: 1.5 MB, 16 pages; Powerpoint presentation at the PVTGs seminar Conservation of Particularly Vulnerable Tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands; Anthropology Professor of New Delhi University and the Anthropological Survey of India).

- ↑ Alard von Kittlitz: The Sentinelese - the most isolated people in the world. “You can't pretend that it doesn't exist”. (No longer available online.) FAZ , February 9, 2010, archived from the original on February 4, 2012 ; accessed on February 17, 2018 .

- ↑ George Weber: Chapter 8: The Andamanese: The Tribes. (No longer available online.) March 30, 2006, archived from the original on May 20, 2013 ; accessed on February 15, 2019 .

- ↑ Christoph Brumann: Ethnology of Globalization: Manuscript of the lecture in SS 2008 Institute for Ethnology University of Cologne. (PDF: 1.1 MB; 263 pages) (No longer available online.) University of Cologne, July 11, 2008, p. 216 , archived from the original on May 17, 2014 ; accessed on February 15, 2019 .

- ^ A b SS Sarkar: The Jarawa of the Andaman Islands. In: Anthropos. Volume 57, No. 3/4/5/6. Friborg 1962, pp. 670-677 (English; JSTOR 40455833 ).

- ↑ a b c Vishvajit Pandya: The Specter of 'Hostility': The Sentinelese between Text and Image. In: The same: In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858-2006). University Press of America, Lanham MD 2009, ISBN 978-0-7618-4153-1 , pp 326-364 (English; Extract in the Google Book Search).

- ^ Stefan Kirschner: Don't Let the Jarawa Become Another Onge. In: Indigenous Policy Journal. Volume 23, No. 1, 2012, pp. ?? (English; ISSN 2158-4168 ; online at indigenouspolicy.org).

- ↑ Sita Venkateswar: The Andaman Islanders. In: Spektrum.de . July 1, 1999, accessed February 15, 2019 .

- ↑ a b wreck entry: MV Primrose [+1981]. In: Wrecksite.eu. July 8, 2017, accessed February 15, 2019.

- ↑ a b Kerstin Rottmann: You survived the tsunami - and so did your fire. Welt Online , November 24, 2018, accessed February 15, 2019.

- ↑ Some Sentinelese artifacts by Maurice Vidal Portman in the British Museum Collection: Search: Maurice Vidal Portman. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ↑ Survival International : World's Most Isolated Tribe Threatened By Poachers - Jarawa And Sentinelese People. In: Indigenous Peoples Issues and Resources. Winter Park, September 20, 2010, accessed February 15, 2019 .

- ^ Dennis O'Neil: Small Population Size Effects. In: Modern Theories of Evolution: An Introduction to the Concepts and Theories That Led to Our Current Understanding of Evolution. 2014, accessed February 15, 2019 (English, Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College, San Marcos, California).

- ↑ Zaria Gorvett: Could just two people repopulate Earth? In: BBC.com . January 13, 2016, accessed February 15, 2019 .

- ^ Rainer Leurs: Dread Island North Sentinel Island: Abandoned by all good guests. one day , September 9, 2013, accessed on February 15, 2019.

- ↑ Swaminathan Natarajan: The man who spent decades befriending isolated Sentinelese tribe. In: BBC.com. November 27, 2018, accessed February 15, 2019.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Adam Goodheart: The Last Island of the Savages. In: The American Scholar , Volume 69, No. 4, December 5, 2000, pp. 13-44 theamericanscholar.org .

- ↑ Survival International : The most isolated people in the world? In: Survivalinternational.de. Retrieved February 15, 2019 (undated).

- ^ Kavita Arora: Indigenous Forest Management In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India . Page 94.

- ↑ a b Barbara A. West: Andamanese (Andaman Islander, Mincopie). In: Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-8160-7109-8 , pp. 44–46, here p. 45 (English; side view in the Google book search).

- ^ Prem Vaidya: Man in Search of Man - Andaman Peoples on YouTube , 1974 (English; 16 minutes).

- ↑ Survival International Germany: In the greatest isolation. In: Survivalinternational.de. Retrieved on February 15, 2019 (with video 2:20 minutes, English, undated).

- ^ Vishvajit Pandya: The Specter of 'Hostility': The Sentinelese between Text and Image . In: In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858-2006) . University Press of America, Lanham MD 2009, ISBN 978-0-7618-4153-1 , p. 342.

- ↑ Video from Terra X: Nature & History : North Sentinel Island: No Entry! (from 0:07:40) on YouTube, June 16, 2019, accessed on January 6, 2020 (4:50 minutes).

- ↑ J. Oliver Conroy: The life and death of John Chau, the man who tried to convert his killers. In: The Guardian. February 3, 2019, accessed February 15, 2019; Quote: "Is this 'Satan's last stronghold', he asked God - a place 'where none have heard or even had a chance to hear your name?'".

- ^ International Religious Freedom Briefing. Samuel D. Brownback, Ambassador at Large for International Religious Freedom, February 7, 2019, accessed February 23, 2019 .