Revitalization (ethnology)

Revitalization is a collective term from ethnology for the revival of certain traditions and / or values in societies that have had negative experiences with modernization - in other words, with increasing cultural assimilation up to assimilation into the dominant modern world society.

Such developments can be triggered by colonial pressure , loss of power, oppression , marginalization or existential economic hardships. The cultural change is reflected and the values of modern culture be questioned. Revitalization reacts to change, gives it a new direction and at the same time drives it.

Revitalization movements can develop

- relate to religious ideas (→ ritual revitalization)

- the return to traditional cultural elements (→ retraditionalization)

- or in the comprehensive "innovative reinvention" of tradition (→ re ‑ indigenization)

- and they lie in a field of tension from the passive-peaceful marketing of folklore (→ folklore)

- up to the “aggressive-irrational” resistance ideology (→ traditionalism) .

However, the terms mentioned are not always clearly differentiated from one another.

Revitalization is often described in indigenous communities around the globe, but it also occurs in nations that want to distance themselves from Western culture .

Ritual revitalization

As a rule, traditional cultures tend to be “ cold societies ”, which means that their members identify intensively with their community through shared values, myths , rites and their cultural heritage . In contrast, contact with the modern world leads to an increasing individualization of people. This in turn often results in a division of society into “modernists” and “traditionalists”. While the modernists accept everything new and integrate it into their culture in various ways, the traditionalists reject it and instead consciously turn to traditional structures. In this case, this applies less to the adoption of new everyday objects or economic practices, but rather to ideological things. If the group then experiences negative experiences with the dominant culture, a ritual revitalization can proceed from the traditionalists - a return to the ritual practices and beliefs of the ancestors, combined with the expectation of salvation for a better future.

In the past, for example, the cargo cults of Melanesia (rites for the return of the ancestors, but "loaded" with western goods) and various crisis cults , such as the Indian spirit dance movement (evocation of spirits for the return of the buffalo and the Disappearance of the whites).

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union , one can observe a revitalization of classical shamanism among Tuvinians in the Altai : The shamans are no longer denounced or persecuted and the great interest of the West in indigenous spirituality has led to a renewed recognition of the necromancers and healers, the traditional played an important role as "ritual keepers and protectors" in the Siberian cultures.

The return to traditional rites with the exclusion of strangers , as is the case with the sun dance of the prairie Indians , proves the deep conviction of such revitalization. In North America in particular, the attempt to revive old religious practices is a fundamentalist endeavor to reverse the destroyed ethnicity or to create a new overarching identity (→ Pan-Indianism ). This also includes the “ Mother Earth philosophy ”, which many Indians today regard as a traditional idea, although this is not correct.

Today, however, revitalized spirituality is very often influenced by the esoteric scene ( neo-paganism , neo-shamanism ): real shamans - initially from Siberia and North America in particular - have used the new interest of the western world to secure and spread their traditional knowledge . In many cases, however, the dialogue with esotericism has led to adapting the traditions to the wishes of the followers, including foreign ideas and entering into an open dialogue with other cultures. There are examples of this from all continents. Critics point out that the methodology , which is often shaped by wishful thinking, consumption and a modern lifestyle , destroys the holistic, traditional contexts and instead of renewing the ritual traditions, it leads to synthetic and inauthentic worldviews that are hardly based on their indigenous roots.

Retraditionalization

When societies reactivate certain parts of their traditional way of life and reintegrate them into everyday life, it is commonly referred to as retraditionalization . This can refer to the revival of individual folklore aspects or to the existential return to traditional economic methods .

Retraditionalizations are often not associated with a re-emerging ethnicity.

In modern societies, the recourse to traditional gender roles or the traditional bourgeois family model is referred to as the retraditionalization of gender roles or the division of labor.

Return to traditional economics

In regions that still have sufficiently large and intact wilderness areas, traditional forms of subsistence are resumed when the modern economic basis collapses or when the dependence on state support payments is to be reduced. Of course, some modern aids (firearms, motor vehicles, mobile phones, etc.) are used.

The small indigenous peoples of Russia are an example of the inevitable retraditionalization of the traditional subsistence economy : After the collapse of the Soviet Union, their economic situation deteriorated drastically. Suddenly the people, previously (forcibly) organized in reindeer collective farms or hunting cooperatives, were left to their own devices and exposed to the principles of the free market. In order to escape the onset of hardship, many indigenous Siberians returned to their earlier way of life outside of the money economy.

Some Aboriginal groups in the remote outstations of western and northern Australia have been eating some (5 to 50%) of bush food again since their land rights were cleared in the 1970s . Animals (in addition to native species and feral cats) are hunted using traditional methods (e.g. spears, fire) as well as guns and cars. In this way, people reduce their dependence on government support.

Repopulation of folklore

The folklore of ethnic group is the sum of their material culture , the traditions , customs , music and art as well as the cults and rites (in this form of revitalization, however, without reference to their ideological background) .

Often folklore is “the last surviving expression” of a culture's ethnicity and the individual's identification with the original community. If such cultural expressions are revived and accepted by younger people too, they are to be seen as retraditionalization. On the one hand, this is deliberately used towards the public - for example as a strategic means to draw attention to grievances or to showcase the strengthened ethnic identity . On the other hand, it is about the preservation or reactivation of former social structures within society - such as the powwow events of North American Indians. It should be noted that the folkloric elements not only correspond to the historical specifications, but are often subject to significant change. The Powwow dancers mix characteristics of different tribes and the costumes are changed, more colorful and more elaborate than before. Another example are Sami fashion designers from Sweden who are trying to establish garments that combine traditional and modern elements.

The re-use of folklore must not be confused with the so-called " folklore ", which has completely different motives.

Folklore

The weakest form of retraditionalization is folklore : the pure marketing of cultural goods or the politically motivated use of folk elements, provided that they have been removed from the traditional context and only serve the interests mentioned. These are, for example, shamanistic ceremonies for tourists in Lapland (shamanism has been extinct there since the 19th century) or the trade in handicrafts according to the ideas of the buyer (Indian dream catchers with a metal ring instead of a branch, bracelets with indigenous patterns and made from natural materials from South America or Africa Masks).

The adoption of folklore elements from foreign cultures, which are associated with an allegedly homogeneous culture as clichés of the western world, are also referred to as folklore. This phenomenon can be found, for example, with North American Indians, who use the traditional equipment of the prairie tribes in order to correspond to the western image of the Indian, although this clothing does not occur in their own culture.

It is often difficult to judge whether it is a “real revival of folklore” or just a superficial “folklore”. The motives are decisive: does folklore play another role in culture besides its commercial or political use? Is it still part of the lived, identity-forming culture, rites and other forms of expression? Then it's not just folklore.

Re-indigenization

The counter-movement to the complete assimilation of an ethnic group into modern society - in other words: identification with modern culture, but often socially “uprooted” and with a marginalized lifestyle. Mother tongue and traditional myths and rituals are increasingly disappearing and are only passed on as fragmentary, historical narratives. Traditional modes of subsistence lose their existential meaning - is denoted by the term indigenization .

Indigenization means reacting innovatively to the confrontation with another culture : The goal is to preserve and strengthen the cultural identity in the context of an authentic new construction and to convey own or foreign cultural elements of any kind to a "modified tradition". In this sense, every indigenization process is not a tradition , but a self-chosen form of modernization .

If a culture is already largely assimilated, dissatisfaction, poverty , racism and frustration can lead to re ‑ indigenization : to a revival of traditional elements in the (adopted) modern culture as part of a general re-strengthening of ethnic identity. The term “indigenization” is often used synonymously for “re ‑ indigenization” if it is clear from the context what exactly it is.

As a rule, such developments require political and social framework conditions that allow indigenization / re-indigenization. This includes representing indigenous peoples and their rights at the United Nations ( Permanent Forum on Indigenous Affairs , UN Working Group on Indigenous Peoples , etc.), obtaining territorial self-determination in autonomous regions (e.g. Nunavut , Greenland ) and states (e.g. B. Bolivia , Zimbabwe ) or the recognition of their cultures by the world public as well as the idea of multiculturalism . According to Samuel P. Huntington , indigenization / re-indigenization is a process of identity creation that always involves a combination of ethnic culture, power and political institutionalization.

In contrast to other forms of revitalization, re-indigenization is therefore always organized in a targeted manner and should lead to a sustainable , but also (in the modern sense) expedient and profitable revival of certain traditional cultural elements. Since their development does not come from the broad population base of an ethnic group, but from certain groups, there is sometimes fierce resistance from within their own ranks. On the one hand, for example, the conscious abandonment of subsistence economy activities fuels fear of increasing dependence on state welfare or market-economy constraints. On the other hand, assimilated indigenous people often prefer to distance themselves from their supposedly “primitive and underdeveloped” culture instead of “reinventing” it. Another area of conflict lies in the different assessments of the authenticity of the intended measures: Is it authentic when a group refers to cultural-religious conditions that existed after Christianization or to a historical identity that has already been creolized ?

It is only when the majority of the ethnic group supports the “resurgence” of the indigenous identity that we can speak of a radical cultural change, of a “renaissance of the suppressed culture”.

A striking example of re-indigenization are the Colombian Paez , one of the great indigenous peoples of South America. They live on 21 reserves in the inaccessible Andean region of Tierradentro . As a reaction to increasing drug-related crime and the social grievances that came with it, a re-indigenization movement emerged in 1971 which, in addition to fighting for land rights, tried hard to strengthen ethnic awareness. The movement is based on an intellectual elite whose aim is to banish foreign cultural elements and to revive the pre-Columbian heritage as much as possible. This applies both to the ritual revitalization of the old religion and shamanism, as well as to many other cultural elements. In 1994 there was a devastating earthquake in the southern tribal area, which clearly solidified and accelerated the process. The shamans interpreted this as a warning shot from Mother Earth and other numinous spirit powers, because the Indians followed the commercial western lifestyle, which had already caused great damage to the life-saving environment.

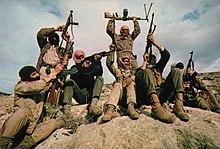

Traditionalism: slowed down revitalization

In contrast to “real” revitalizations, which are all action-oriented, cause active change and - in whatever way - represent appropriate reactions to the real conditions, one speaks of traditionalism in the case of political movements that are predominantly ideological . Here, too, the confrontation with modernity gives rise to a return to previous norms and values, as initiated by certain population groups during indigenization; but to be assessed as an irrational political ideology due to the following characteristics :

- Reference to "ancient traditions" that are, however, in fact fabricated, misinterpreted or imagined

- Unreflected "cementing" of these alleged traditions without comparison with the real conditions

- Tradition to conceal actual interests, to justify certain actions and to secure positions of power

- The blame for any undesirable developments is blamed on other cultures in an aggressive, propagandistic way

- Revitalization is an active cultural change. Traditionalism, on the other hand, tends to stand still.

Such tendencies can be observed , for example, in Iran after the overthrow of the Shah . Traditionalism in Islam is considered to be one of the main causes of modern Islamism .

See also

literature

- Karl-Heinz Kohl : Ethnology - the science of the culturally foreign: An introduction. 3rd, revised edition, CH Beck, Munich 2102, ISBN 978-3-406-46835-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 25, 80, 188, 215, 251.

- ↑ Dieter Haller u. Bernd Rodekohr: dtv-Atlas Ethnology. 2nd completely revised and corrected edition 2010, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-423-03259-9 . P. 89.

- ↑ a b Walter Hirschberg (founder), Wolfgang Müller (editor): Dictionary of Ethnology. New edition, 2nd edition, Reimer, Berlin 2005. p. 314.

- ↑ a b Birgit Bräuchler and Thomas Widlok: The Revitalization of Tradition: In the (negotiating) field of action between state and local law. In: Journal of Ethnology. Vol. 132, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2007, pp. 5-14.

- ↑ Annemarie Gronover: Theorists, ethnologists and saints: approaches of cultural and social anthropology to the Catholic cult. LIT-Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8403-1 . Pp. 25-62, especially 61-62.

- ↑ Anett C. Oelschlägel: Plurale Weltinterpretationen - The example of the Tyva of South Siberia. Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology, SEC Publications / Verlag der Kulturstiftung Sibirien, Fürstenberg / Havel 2013, ISBN 978-3-942883-13-9 . Pp. 31, 60f.

- ↑ Christian F. Feest : Animated Worlds - The religions of the Indians of North America. In: Small Library of Religions , Vol. 9, Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-451-23849-7 . Pp. 29, 55-59.

- ↑ Dawne Sanson: Taking the spirits seriously: Neo-Shamanism and contemporary shamanic healing in New Zealand. Massay University, Auckland (NZ) 2012 pdf version . Pp. I, 28-31, 29, 45-48, 98, 138, 269.

- ↑ Uta Dossow: Traditional patterns in a new guise. Dodger cloth and Mmaban cloth. In: Baessler archive - contributions to ethnology. Volume 52, D. Reimer, Berlin 2004, ISSN 0005-3856 . P. 208.

- ↑ Manfred Quiring: UN aid project for reindeer herders . Website of the Berliner Zeitung. Article of November 26, 1997.

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 86-88.

- ↑ Eckhard Supp: Australia's Aborigines: End of the dream time ?. Bouvier, 1985, ISBN 978-3-4160-1866-1 . Pp. 239, 303-306.

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 215-216.

- ↑ a b Hans Schulz u. Gerhard Strauss / Institute for German Language (Ed.): German Foreign Dictionary: Eau de Cologne-Futurism. Volume 5, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-018021-9 . Pp. 995-1001.

- ↑ Valerie Gräser, Johannes Nickel a. Emanuel Valentin: Ethnological symposium of the students: Ritualizing a Revival. In: Cargo. No. 27, 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Product knowledge wild rice: The black delicacy from Canada . In: schrotundkorn.de, published in print edition 05/1999, accessed on March 17, 2015.

- ↑ Jacqueline Knörr: Postcolonial Creolity versus Colonial Creolization. In: Paideuma 55. pp. 93-115.

- ↑ Jörg Steinhaus: The clash of cultures. Just a new enemy image? Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Institute for Sociology, winter semester 1997/98. P. 13.

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 168-172.

- ↑ Ute Rietdorf: Minorities and their significance for endogenous developments in Africa: the example of Tanzania. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 978-3-8300-0896-5 . Pp. 104-112.

- ↑ a b Eva Gugenberger: Title. LIT-Verlag, Münster 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-50309-1 . Pp. 58-59.

- ^ Thomas Küster (Ed.): Regional identities in Westphalia since the 18th century. Westphalian research, Volume 52, Aschendorff, Münster 2002, ISBN 978-3-402-09231-6 . Pp. 232-238.

- ↑ Winona LaDuke : Minobimaatisiiwin: The Good Life . In: culturalsurvival.org, 1992, accessed March 16, 2015.

- ↑ a b Josef Drexler: Eco-Cosmology - the polyphonic contradiction of Indian America. Resource crisis management using the example of Nasa (Páez) from Tierradentro, Colombia. Lit, Münster 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Julia Vorhölter: Youth at the Crossroads - Discourses on Socio-Cultural Change in Post-War Northern Uganda. In: Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Göttingen University Press, No. 7, 2014, pp. 4–16.

- ↑ Stars as Hope for New Zealand's Maori - Better Integration of the Polynesian Natives. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung from July 18, 2005.

- ↑ Kohl. P. 25.

- ↑ Hermann Mückler u. Gerald Faschingeder: Tradition and Traditionalism. For the instrumentalization of an identity concept. Promedia Verlagsgesellschaft, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-85371-343-3 .

- ↑ Norbert Hintersteiner (Ed.): Transgressing traditions: Anglo-American contributions to intercultural traditional hermeneutics. Edition, facultas.wuv / maudrich, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-85114-550-X . Pp. 66-68.

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 25, 215.

- ↑ Traditionalism . In: bpb.de, Federal Agency for Civic Education: Kleines Islam-Lexikon , accessed on March 20, 2015.