Indigenization

Indigenization is a form of cultural change in which traditional societies take on "something foreign ", accept it and innovatively integrate it into their traditional culture as "something of their own" .

If, in the opposite case, it is a matter of specifically organized and sustainable efforts to revive traditionally individual cultural elements in a new form, one speaks of re-indigenization . However, this process is often undifferentiated as indigenization.

Indigenization / re-indigenization is often a counter-movement to assimilation into modern civilization ; a reaction to confrontation with another culture. In contrast to the diffusion of individual cultural elements, there is not just a simple addition, but a comprehensive reinterpretation of the new with the aim of preserving and strengthening the cultural identity in the context of an authentic new construction to a "modified tradition".

In this sense, every indigenization process is not a tradition , but a self-chosen form of modernization that can relate to all cultural elements - subsistence, folklore , language, customs .

As a rule, such developments require appropriate political and social framework conditions. This includes representing indigenous peoples and their rights at the United Nations ( Permanent Forum on Indigenous Affairs , UN Working Group on Indigenous Peoples , etc.), obtaining territorial self-determination in autonomous regions (e.g. Nunavut , Greenland ) and states (e.g. B. Bolivia , Zimbabwe ) or the recognition of their cultures by the world public as well as the idea of multiculturalism . According to Samuel P. Huntington , indigenization / re-indigenization is a process of identity creation that always involves a combination of ethnic culture, power and political institutionalization.

Indigenization of traditional communities

Since the time of the European expansion on earth, most of the non-European peoples have been the cultures of the conquerors in the form of colonization , exploitation , slavery , expulsion , oppression , Christianization etc. up to the planned ethnocide ; but also exposed solely through contact with modern technologies and attitudes . As always with the contact of different ways of life, extensive processes of change were initiated from the beginning. The dominance of Europeans led to acculturation processes , especially in non-industrialized societies .

Indigenization opposes this trend in that those affected try to evaluate the foreign influences against their own background and to appropriate the beneficial elements in such a way that they fit harmoniously into traditional cosmology .

Examples of such forms of indigenization are, for example, the emergence of Indian equestrian cultures through the adoption of the horse, the Navajo sheep breeding , the building of churches in the style of indigenous cultures, the introduction of chief posts in previously non-dominant ( acephalous ) societies or, more recently, the use of modern political ones Means in the fight against foreign rulers.

The Asháninka of the Peruvian-Brazilian border area are a well-known example of efforts to harmoniously integrate modern cultural elements: They reforest destroyed rainforest areas and teach foreigners the methods of their sustainable agriculture in a specially established school. In addition, they have an internet connection via a photovoltaic system, which they can use to contact the authorities if the “tropical wood mafia” turns up.

From the tropical rainforests - where most of the earth's traditional communities still live - many examples are known in which ethnic groups indigenize certain values and ideas of the West in the hope of being recognized by the world community. For example, they appear as “incorruptible keepers of natural diversity” and transform their actual respect for “mother earth” into ideology . Western conservationists exploit the supposedly original philosophy and elevate the indigenous peoples to "noble savages" who do not harm any animal or tree. This picture is of course not authentic and quickly leads to the opposite of what the people wanted to achieve, because both traditional hunting and the sale of logging licenses in order to generate some money for the tribal treasury are then viewed by many ignorant Western sympathizers as “treason by tradition ”.

Re-indigenization of assimilated communities

In the advanced stage of assimilation, a great cultural distance and the above-mentioned events since the 16th century very often lead to far-reaching negative consequences ( "uprooting" , marginalization , increasing dependencies, loss of traditions, etc.).

Under such circumstances, dissatisfaction, poverty , racism and frustration can lead to re-indigenization : Traditional cultural elements are reinterpreted and revived in the (adopted) modern culture. In contrast to indigenization, re-indigenization is always organized in a targeted manner and is a sustainable , but also (in the modern sense) expedient and profitable strategy which, in addition to material benefits, is primarily intended to strengthen the “we-feeling” .

Indigenization in modernized societies

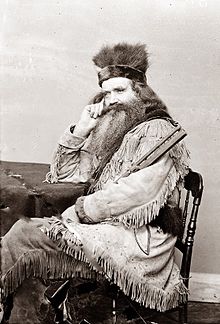

Of course, cultural contact can also lead to changes in the dominant culture. This applies, for example, to the trappers and mountain men as well as many residents of the border areas during the European settlement history of North America, who adopted styles of clothing, jewelry and various customs from the neighboring Indians.

In general, the term indigenization is also related to the integration of new cultural patterns in western societies, for example in the music genre rap . Here, too, there is a reinterpretation of elements taken over from traditional cultures in the sense of adaptation to one's own culture.

Finally, the turning away from Eurocentric thinking and the return to traditional ideas, expressions and perspectives in already strongly modernized societies is called indigenization. One example of this is ethnology in the Arab world, which is increasingly making use of “non-Western” theoretical paradigms and methodological approaches.

State decreed indigenization and indigenism

If the preservation and promotion of indigenous traditions with a view to socially acceptable integration is based on state (i.e. mostly non-indigenous) institutions, one speaks of indigenism . There are some examples of this from Mesoamerica .

In contrast to the other continents, traditional communities in sub-Saharan Africa tend to form the majority of the population. Many traditional structures have been preserved here despite the long colonial history. In times of globalization , the pressure of world culture increases considerably. The economy of the African states in particular is forced to submit to the “global rules of the game” if they want to benefit from them in the future. In Zimbabwe there are efforts to indigenize the economy: With the help of an "indigenization law", foreign companies are to be forced to surrender at least 51 percent of the company shares to the Zimbabweans. There are also initiatives in Rwanda and Tanzania to separate modern progress from colonial heritage and to harmonize it with tradition.

See also

- Revitalization (ritual revitalization, retraditionalization, folkloreization, traditionalism)

literature

- Karl-Heinz Kohl : Ethnology - the science of the culturally foreign: An introduction. 3rd, revised edition, CH Beck, Munich 2102, ISBN 978-3-406-46835-3 .

Applications literature

- Kumoll, Karsten, Hermann Schwengel, and D. Sahlins Marshall. "Culture, History and the Indigenization of Modernity." An analysis of the complete works of Marshall Sahlins. [Culture, History and Indigenization of Modernity. An Analysis of the Complete Works of Marshall Sahlins.] Bielefeld (2007).

- Trenk, Marin. "World monoculture or indigenization of modernity." Zeitschrift für Weltgeschichte 3.1 (2002): 23–39.

- Knörr, Jacqueline. "Indigenization versus re-ethnicization. Chinese identity in Jakarta." Anthropos (2008): 159-177.

- Delgado, Mariano. "Creolization, indigenization and mestizization as forms of intercultural hybridization in Latin America." Tertium Datur !: forms and facets of intercultural hybridity, Formes et facettes d'hybridité interculturelle 40 (2013): 163.

- Black, Inga. Anthropology of governance in education: Indigenization of alternative educational concepts in Turkey. Berlin; Münster: LIT, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ute Rietdorf: Minorities and their significance for endogenous developments in Africa: the example of Tanzania. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 978-3-8300-0896-5 . Pp. 104-112.

- ↑ Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin u. Ulrich Braukämper (Ed.): Ethnology of Globalization: Perspectives of cultural entanglements. D. Reimer, Berlin 2002, ISBN 978-3-4960-2737-9 . P. 16.

- ↑ Jacqueline Knörr: Postcolonial Creolity versus Colonial Creolization. In: Paideuma 55. pp. 93-115.

- ↑ Jörg Steinhaus: The clash of cultures. Just a new enemy image? Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Institute for Sociology, winter semester 1997/98. P. 13.

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 168-172.

- ↑ Eva Gugenberger: Title. LIT-Verlag, Münster 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-50309-1 . Pp. 58-59.

- ^ Thomas Küster (Ed.): Regional identities in Westphalia since the 18th century. Westphalian research, Volume 52, Aschendorff, Münster 2002, ISBN 978-3-402-09231-6 . Pp. 232-238.

- ↑ Martina Grimmig: Golden Tropics: The Coproduction of Natural Resources and Cultural Difference in Guiana. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-89942-751-6 . P. 246.

- ^ Walter Hirschberg (founder), Wolfgang Müller (editor): Dictionary of Ethnology. New edition, 2nd edition, Reimer, Berlin 2005. p. 34.

- ↑ Raul Páramo-Orgega: The trauma that unites us. Thoughts on the Conquista and Latin American identity. In: Psychoanalysis - Texts on Social Research. 8th year, issue 2, Leipzig 2004, pp. 89–113.

- ↑ Kohl. Pp. 168-172.

- ↑ Birgit Bräuchler and Thomas Widlok: The Revitalization of Tradition: In the (negotiating) field of action between state and local law. In: Journal of Ethnology. Vol. 132, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2007, pp. 5-14.

- ↑ Winona LaDuke : Minobimaatisiiwin: The Good Life . In: culturalsurvival.org, 1992, accessed March 16, 2015.

- ↑ Volker Gottowik, Holger Jebens, Editha Platte (ed.): Between appropriation and alienation: Ethnological ridge walks. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38873-1 . Pp. 109-111.

- ↑ Solveig Lüdtke: Globalization and localization of rap music using the example of American and German rap texts. Edition, LIT-Verlag, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-0228-8 . P. 312.

- ↑ Katharina Lange: "Bringing back what belongs to us" Indigenization tendencies in Arab ethnology. transcript-Verlag, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 978-3-89942-217-7 .

- ^ Walter Hirschberg (founder), Wolfgang Müller (editor): Dictionary of Ethnology. New edition, 2nd edition, Reimer, Berlin 2005. pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Daniel Pelz et al. Adrian Kriesch Where is Zimbabwe's economy headed? . In: dw.de - Internet presence of Deutsche Welle, Bonn, July 31, 2013, accessed on March 23, 2015.

- ^ Rwanda - Indigenization of Development . In: iofc.org - Initiatives of Change, Caux (CH), September 20, 2013, accessed on March 23, 2015.

- ↑ Ulrike Brizay: Coping strategies for the orphan crisis in Tanzania: Lifeworld-oriented support offers for the orphans. Springer-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-531-18110-3 . Pp. 47-51, 316, 511.