Drug crime

The term drug crime is not precisely defined. The EU Drugs Action Plan saw (2005-2008) provides that in the European Union , the work on prevention of drug offenses in 2007, a common definition of 'drug-related crime "(as part of the intensification English drug-related crime should be) fixed. The Council of the European Union already pursued this intention in the previous Drugs Action Plan (2000–2004). In 2007 the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction published a definition. However, there is still no official definition of the EU .

term

Definitions

The term drug crime is defined very differently in the various scientific disciplines and by experts. According to the definition of the Duden , drug-related crime is the totality of criminal acts that are committed under the influence of drugs and drug- related crime is crime related to or under the influence of drugs.

In 2007 the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction in Lisbon developed a definition of drug-related crime for the EU. She found that any attempt to create a standard definition for such a complex phenomenon as drug crime is inevitably reductive. It also concluded, among other things, that a clear definition of drug-related crime is necessary in order for an assessment to be made.

According to the definition published by the European Observatory, drug-related crime can be divided into the following four categories:

- Psychopharmacological crimes: crimes committed under the influence of psychoactive substances as a result of acute or chronic consumption.

- Offenses for economic constraints: offenses that are used to obtain money (or drugs) for drug use.

- Systemic offenses: offenses that are committed within the framework of illegal drug markets and that are related to drug trafficking and drug use.

- Drug Law Violations: Crimes that violate drug law (and other related laws).

Demarcation

In German-speaking countries, the term drug crime is often used in the same context as the word drug crime . In addition to drug- related crime, direct procurement crime is increasingly subsumed under the term drug-related crime.

In Germany, all criminal offenses under the Narcotics Act (BtMG) as well as theft to obtain narcotics, the theft of narcotics from pharmacies, doctor's surgeries, hospitals, from manufacturers and wholesalers, the theft of prescription forms and forgery to obtain drugs are covered by the police in Germany under the term drug crime Narcotics summarized. To direct drug-related crime belong in Germany to the police crime statistics , the crime robbery to obtain narcotic drugs, theft of drugs from pharmacies, doctors' offices, hospitals, manufacturers and wholesalers, the theft of prescription forms and the falsification to obtain narcotic drugs.

The German Federal Criminal Police Office distinguishes between three types of drug crime:

- Consumption-related offenses - General violations of the Narcotics Act (BtMG) = offenses according to Section 29 BtMG, which include the possession, acquisition and delivery of BtM as well as similar offenses.

- Trade offenses - offenses of the illegal trade in and smuggling of drugs according to § 29 BtMG as well as the offenses of the illegal import of BtM according to § 30 para. 1 No. 4 BtMG.

- Other violations - Illegal cultivation of BtM (Section 29 Paragraph 1 No. 1 BtMG), BtM cultivation, manufacture and trading as a member of a gang (Section 30 Paragraph 1 No. 1, 30 a), provision of funds or similar assets (Section 29, Paragraph 1, No. 13), advertising for BtM (Section 29, Paragraph 1, No. 8), delivery, administration or transfer of BtMs to minors (Section 29a, Paragraph 1, No. 1, possibly § 30 para. 1 no. 2), carelessly causing the death of another by dispensing, administering or releasing BtM for direct consumption (§ 30 para. 1 no. 3), illegal prescription and administration by doctors (§ 29 para . 1 No. 6) and illegal trade in or production, supply, possession of BtM in not small quantities (§ 29 a Paragraph 1 No. 2).

This so-called drug crime is seen by some representatives of social science addiction research as a victimless crime .

Jargon in the drug environment

Over the years, the drug scene has developed its own language, which was particularly influenced by the youth subcultures in the 1960s and the increased criminalization of drug users. The scene expressions, many of which come from English, have a "technical language character". With drug jargon , scene members isolate themselves from the outside world (e.g. non-users, parents, police). The scene language supplements or replaces the colloquial language in the drug environment.

history

People have been using drugs for a variety of reasons for tens of thousands of years. There was evidence of critical views regarding the consumption of individual drugs even in pre-Christian times (e.g. the ban on bacchanalia by the Roman Senate ). Intoxicants used in one culture for religious acts or medical treatment were not allowed in other social cultures at the same time.

In Germany, a food law regulation regulated the handling of drugs as early as the 16th century. In 1516, the Bavarian purity law stipulated that the very toxic and hallucinogenic plant henbane could no longer be added to German beer. There were also bans in other countries, for example efforts in the 18th century in China to ban the consumption and import of opium. Because of this, England began two wars with China. In the First Opium War (1839–1842) and Second Opium War (1856–1860) England fought for the withdrawal of the opium ban.

In the 19th century, scientists isolated active ingredients such as morphine , caffeine and cocaine for the first time . These substances were sold globally by pharmaceutical companies until the 1920s. The first restrictions on some substances came into force earlier in Germany. In 1901 the Reichstag issued a regulation for the dispensing of morphine in pharmacies. Since 1901 there have also been temporary prohibitions on alcohol . In German-speaking countries, the term prohibition is predominantly associated with the prohibition on alcohol in the United States from 1919 to 1933 .

A number of international opium and drug abuse conferences were held between 1909 and 1925. The conferences in Shanghai (1909) and The Hague (1912, 1913, 1914) led to legal regulations also in Germany (1920). According to the American sociologist JR Gusfield, the first conference in The Hague (1912) marked the start of the “symbolic crusade against drugs”. Four years after the two Geneva Opium Conferences (1924/25), Germany implemented the international regulations in 1929 its own opium law. Further international narcotics agreements followed after World War II .

One year after the Second World War, the occupying powers introduced criminal police statistics in their zones of occupation in 1946, but these differed so widely that a summary of the results for only a few crime groups as a contribution of the Federal Republic of Germany to the International Crime Statistics of the Interpol General Secretariat since 1950 was possible. Narcotics crime is one of these crime groups (see case numbers 1950–1953).

| Number of drug offenses in Germany 1950–1953 ( source: PKS 2004 ) |

|

| 1950 | 1,737 |

| 1951 | 1.961 |

| 1952 | 1.916 |

| 1953 | 1,746 |

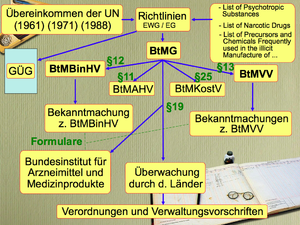

Since the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs , which the United Nations was signed in 1961, many drugs are subject to a global prohibition. In spite of this, the German opium law was only replaced by the law on the traffic in narcotics (BTM law, 1971). When considering the historical development from the Opium Act to the Narcotics Act, it should be noted that the Federal Republic of Germany is not free as to which goals it wants to pursue in the field of drug policy . Rather, it is bound by a number of agreements within the framework of the United Nations (UN) (see table below).

Up until the mid-1960s, drug policy was an extremely small and socially neglected policy area in relation to other areas of politics. Mainly because of the small number of socially conspicuous drug users, the Opium Act was a law without an acute reality of persecution. The number of people convicted under the Opium Act was correspondingly low. At the beginning of the 1960s, this number was two to three convictions per week (between 100 and 150 per year) in the entire Federal Republic of Germany.

The importance of drug and especially cannabis policy changed suddenly at the end of the sixties. This happened against the background of international development (international agreements) and above all the perceived "youth drug problem" in the USA. In Germany, following the lurid example in the United States of America, from the end of the 1960s the press gave the impression of a huge “hashish and drug wave” threatening to overwhelm the country. At the same time, the picture of a dramatic social problem was sketched out in public opinion, which was also associated with what is probably the most important domestic political event of that time, namely the protest movement, which was mainly supported by students and which was known as the " Extra-Parliamentary Opposition (APO) “Had formed.

Against this background, in December 1971 the legislature ( German Bundestag and Bundesrat ) passed the Opium Act of December 10, 1929, which primarily regulated the administrative control of the medical supply of the population with opium, morphine and other narcotics, by means of a new "Act on the Traffic with narcotics (Narcotics Act, BtMG) ”.

New versions followed in 1982 and on March 1, 1994 (Narcotics Act). The Federal Constitutional Court is shortly afterwards on 9 March 1994 in the so-called " Cannabis-decision " (BVerfGE 90, 145 - Cannabis) found that there is no "right to intoxication" in Germany.

In Switzerland and Austria similar laws. In Austria, the Addiction Act 1951 (SGG) came into force. In 1998 the drug law was replaced by the drug law . In the same year on October 3, 1951, the Narcotics Act was passed in Switzerland . A year later, the Swiss Narcotics Act (1952) came into force.

Since 1992 there has been a common drug strategy in the European Union with an EU drug action plan and an EU drug control strategy. Five years later, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) was established.

| year | International Conferences / Agreements in the 20th Century |

|---|---|

| 1909 | Foundation of the International Opium Commission on February 1, 1909 in Shanghai |

| 1912 | International Opium Convention of January 23, 1912 in The Hague |

| 1912, 1913, 1914 | Opium Conferences in The Hague |

| 1924, 1925 | Opium Conferences in Geneva |

| 1925 | International Narcotics Convention of February 19, 1925 in Geneva |

| 1931 | Agreement on the restriction of the manufacture and regulation of the distribution of narcotic drugs of July 13, 1931 in Geneva |

| 1936 | Agreement to suppress unauthorized traffic with BTM from June 26, 1936 in Geneva |

| 1946 | UN, with WHO support, sets up Committee on Drugs, December 11, 1946, supplementary agreements in Lake Success / NY |

| 1948 | Additional protocol of November 19, 1948 from Paris on the international control of certain substances |

| 1953 | Opium production and poppy cultivation are restricted, minutes of June 23, 1953 in New York |

| 1961 | Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs ( standard agreement on narcotic drugs ) |

| 1971 | Convention on “Psychotropic Substances” of February 21, 1971 in New York |

| 1972 | Protocol Amending the Single Convention (1961) on March 25, 1972 in Geneva |

| 1988 | UN Convention against the Illicit Consumption of Psychotropic Substances and Narcotic Drugs of December 20, 1988 in Vienna |

| 1992 | EU Drugs Action Plan / EU Drug Control Strategy |

| 1995 | Convention against the Illicit Traffic of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of January 31, 1995 in Strasbourg |

phenomenology

The causes for every drug use, a drug career or drug addiction are different. The reasons for drug-related crime also lie in this context. The first contact with illegal drugs usually takes place in a phase of life that is characterized by phases of tension. In this phase, the use of intoxicants assumes psychosocial functions for children and adolescents. For example, the use of illegal drugs can open up access to cliques, serve to satisfy curiosity or be a form of social protest.

Intoxicant addiction always has a story. A popular theory is that of the so-called illegal gateway drug , which has been refuted by several studies. In the case of severe drug abuse or after the onset of addiction , the person concerned can no longer or only to a limited extent pursue a regular life. In science there are different explanations or theories regarding the development of addiction. The best-known model for the development of addiction is the multifunctional factor or cause model (so-called addiction triangle by Kielholz & Ladewig, 1973). It takes into account the three essential components of addictive substances, the environment and people.

There are several scientific studies on the relationship between drug addiction and crime. However, the current state of research does not allow any general statements about the relationship between drugs and delinquency . Delinquency and addiction, drug careers and criminal careers may not have a causal connection, but rather develop from a lifestyle that can be described as deviant and deviates from social norms and values. The fact that criminal law in general, and especially custodial sanctions, is only suitable to a limited extent to prevent future criminal offenses, is now considered to be criminologically proven.

Despite knowing these facts, every state regulates the manufacture, distribution, marketing, and sale of some or all drugs. The so-called hard drugs are generally prohibited without restriction. The reasons for drug bans (such as public health) are complex, as are the effects of those bans. Some examples:

- Law enforcement in the field of drug-related crime is largely determined by the behavior of the police. In contrast to many other areas of crime, drug offenses are so-called victimless offenses in which reporting by third parties plays only a very minor role, so that the proactive approach of the supervisory authorities is of crucial importance for the official registration and formal sanctioning of these offenses .

- The illegality of drugs goes hand in hand with the criminalization of those who buy or sell them. Illegal drugs tend to be expensive. For this reason, the person concerned often finances his addiction through crime or prostitution .

- Drugs that are classified as illegal are also given a special status for some people and convey a feeling of being different. In the context of a lack of acceptance of the norms, this favors the handling of illegal drugs.

- Prohibited drug businesses are lucrative businesses. The shadow economy or criminal persons or organizations benefit from the drug bans.

- The cultivation or sale of drugs is the only source of income for the local population in some regions of the world. People who finance their livelihood by growing drugs are criminalized by drug bans.

Extent of drug crime

| year | number |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 244,336 |

| 2001 | 246,518 |

| 2002 | 250,969 |

| 2003 | 255.575 |

| 2004 | 283,706 |

| 2005 | 276.740 |

| 2006 | 255.019 |

| 2007 | 248.355 |

| 2008 | 239,951 |

| 2009 | 235,842 |

| 2010 | 231.007 |

| 2011 | 236.478 |

| 2012 | 237.150 |

| 2013 | 253,525 |

| 2014 | 276.734 |

| 2015 | 282,604 |

| 2016 | 302,594 |

| 2017 | 330,580 |

| 2018 | 350,662 |

| 2019 | 359,747 |

Violations of the Narcotics Act are typical control offenses , i. This means that these crimes can only be discovered through controls by the police or security personnel.

In 2018, a total of 350,662 drug offenses were recorded in the federal situation report of the Federal German Federal Criminal Police Office; which corresponds to an increase of 6.1% compared to the previous year. The number of consumption-related offenses (274,787 crimes) also increased by 7.6%, as was the case for trafficking offenses (53,367) - 2.3%. As in 2017, the proportion of drug offenses in total crime was around 6%.

According to the police crime statistics, a total of 1,276 drug deaths (+ 0.3%) were registered in Germany in 2018.

Statistics ( police crime statistics , convict statistics , etc.) cannot be used to determine the exact extent of drug-related crime. Due to different recording periods or data and other influencing factors, these statistics are not comparable in Germany.

The number of detected control offenses also says little about the number of unreported cases . Stricter controls can lead to an increased number of offenses detected, although the number of actual offenses has remained the same or has even decreased. Conversely, the number of offenses detected can also remain the same or even decrease as a result of less frequent controls, although the number of offenses committed has increased.

Dark field

Science therefore also uses so-called dark field studies , such as the study on the drug affinity of adolescents by the Federal Center for Health Education (BZgA), in order to be able to make more precise statements on the extent of drug crime. In principle, however, such surveys do not allow a final assessment of the number of crimes actually committed.

According to the BZgA study (2015) on the drug affinity of adolescents, drug use in Germany is mainly cannabis use. Experience and use of illicit drugs is more common among young adults than among adolescents. Cannabis products such as marijuana and hashish have already been used by 34.5 percent of 18 to 25 year olds in Germany. Another finding of the BZgA study is that illegal drugs play a greater role in male adolescents and young adults than in the group of girls of the same age. Less than one percent of the respondents have experience with the use of crystal meth, crack or heroin.

The results of the BZgA study correlate with two other international dark field studies. On the one hand with the WHO study “Health Behavior in School-aged Children” (HBSC, 2014), which examined the health and health behavior of pupils in the 5th to 9th grade of all types of school in some federal states. Furthermore, with the so-called ESPAD study (European school student study on alcohol and other drugs) by the Institute for Therapy Research (IFT) from 2015.

International drug trade

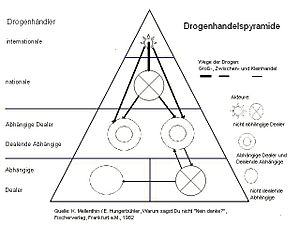

The international drug trade is assigned to the area of organized crime . The annual turnover of illicit drugs is estimated at several hundred billion US dollars. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), only the global oil business achieves the same turnover. According to statements by the Federal Intelligence Service , the international drug trade is the most important area of organized crime in which more than half of all global organized crime sales are made. The drug routes run through international dealers, national dealers, intermediaries to consumers or addicts (see picture of the drug trade pyramid).

In Europe, the drug business was controlled by the mafia drug cartels of the Cosa Nostra , Camorra and 'Ndrangheta until the end of the 20th century . In the USA it was the La Cosa Nostra (in particular through the toleration of the Pizza Connection of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra ), in Asia it was the Triads and the Yakuza , in the Middle East the Lebanon Connection and in Latin America various cocaine cartels, mainly from Colombia and Mexico.

The involvement of the US secret service CIA in the international drug trade has been publicly proven several times. For example, the American history professor Alfred W. McCoy described in detail the involvement of the US secret service in the drug trade in his book "The CIA and Heroin". (see drug trade # secret services )

Well-known cases of organized drug crime

In the past, there has always been a lot of media interest when well-known drug dealers, e.g. B. from South America and the USA, were arrested. In the subsequent trials of the accused, the dimensions of the international drug trade became clear. Individual protagonists who were brought to justice achieved fame. For example:

- Al Capone at the time of Prohibition in the United States 1919–1933

- Marcos Arturo Beltrán-Leyva

- Tommaso Buscetta

- El Chapo

- Pablo Escobar

- Vito Genovese

- John Gotti

- Sammy Gravano

- Howard Marks

- George Jung

- Ouane rat icon

- Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía

- Carlos Lehder Rivas

- Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela

- Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha

Drug growing areas

Drugs are only grown on a large scale in a few regions of the world and brought onto the international market from there by criminal organizations. The drug-growing areas have been in the focus of the global public since the first international agreements. Global drug control has therefore also restricted drug cultivation since the Unified Agreement on Narcotic Drugs (1961). However, cultivation bans mean economic losses for the respective countries.

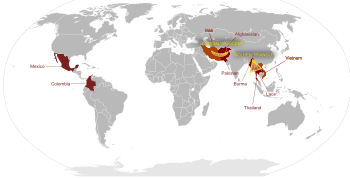

The worldwide opium poppy growing areas (such as the Golden Triangle or the Golden Crescent ) are mainly located in Southwest and Southeast Asia (see picture of opium / heroin growing regions). The importance of the Golden Triangle as a supplier for the global heroin market has noticeably decreased due to drug production in Afghanistan.

The coca- growing areas are in South America (especially in Colombia , Bolivia and Peru ). The cultivation of the coca bush by the coca farmers is only legal in certain quantities in the Andean countries, the processing of the leaves into cocaine or its precursors is strictly prohibited.

Hemp is grown in many countries, sometimes legally under state control. The largest producing countries are Afghanistan and Morocco .

The worldwide annual turnover in drug trafficking is around US $ 400 billion (according to UN 1998).

Albania

In 2018, Albania was the largest marijuana supplier for Europe by western security authorities. For 2018, it is estimated that sales from the marijuana trade by Albanian gangs alone will amount to 4 billion US dollars, which corresponds to about half of the country's gross domestic product. Added to this is its role as a major hub for international heroin and cocaine smuggling.

Afghanistan

In 2005, according to the UNODC, 30-000 hectares of arable land were prepared for the cultivation of cannabis in Afghanistan . This is around a third of the cultivation area in Morocco, the world's largest hemp producer.

In the past few years, Afghanistan has become increasingly important in the cultivation of opium poppies. Half of the gross domestic product (2002) was generated by the opium trade. Most of the international opium poppy crops today come from Afghanistan. In 2005 it is estimated that around 61% of the opiates produced in Afghanistan came to the international market via Iran and 20% via Pakistan .

According to the Afghanistan Opium Survey 2005 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Control (UNODC), opium poppies were grown on a 21% smaller area (only 104,000 hectares) in 2005 compared to 2004. This represented the first reduction in acreage since 2001. However, this success was put into perspective by an increase in productivity . In 2005, the yield fell compared to the previous year by only 2.5% to 4,100 tons. It follows that Afghanistan's share of global opium production in 2005 showed almost no change. With 87% of world production, Afghanistan remained the largest producer of opium in 2005.

The UNODC analysis of satellite images and surveys on the ground shortly before the 2006 harvest show that the opium poppy acreage has increased by 59% compared to 2005. In 2006, according to UNODC information, opium poppies were grown on around 165,000 hectares of agricultural land in Afghanistan. The Vienna UNDOC office assumes that in 2006 approx. 6100 t of opium will be extracted from the harvested opium poppy capsules. Afghanistan's world opium production thus increases to 92%. For this reason, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan (CNPA) has been established in Afghanistan with international support since 2002 .

In 2016, the acreage for opium poppies in Afghanistan grew by 63 percent to 328,000 hectares. Afghanistan produced an estimated 70 to 90 percent of the world's opium in the same year. Around 9,000 tons of opium were produced in 2017. According to the UN, that was 87 percent more than in the previous year. The opium poppy cultivation exceeded the maximum of 224,000 hectares from 2014. The provincial governors therefore had a total of 750 hectares destroyed with poppy fields in 2017.

Bolivia

The Coca -Anbau is one of the main economic sectors of Bolivia , especially in the regions of Yungas and Chapare . In Bolivia, coca is not only a raw material for cocaine, but is also used by the local population as tea (mate de coca) or for chewing. Between 40,000 and 60,000 families (approx. 86%) in the Chapare region make a living from growing coca. The cocaine business in Bolivia has an annual turnover of 1.5 to 2 billion dollars, of which, according to most estimates, between US $ 500 and 700 million remains in the country. In 1997, this was roughly equivalent to a third of legal exports. In spite of the lack of clarity about the actual size of the profits from the coca or cocaine sector, it can be said with relative certainty that these are still substantial. In the face of high unemployment, low wages and a worsening economic crisis, the drug and coca industry creates employment and income for a considerable part of the population of a total of 8 million people. A fierce dispute broke out between the government and the coca farmers over coca cultivation, which led to the chaotic political situation of 2002–2003. The leader of the so-called cocaleros , Evo Morales , ran as a candidate in the 2003 presidential election, but was narrowly defeated in the runoff election. In the elections on December 18, 2005, he received 53.7% of the votes cast and was thus elected President.

On July 1, 2001, Bolivia withdrew from the international drug convention to secure the right of the locals to their coca leaves. It re-acceded to the United Nations Convention on January 10, 2012, subject to Article 50 that it allowed the cultivation, trade and consumption of coca leaves in its country. 15 contracting parties raised objections within one year, which clearly fell short of the quorum required for a rejection by a third of all states. Thus, on January 11, 2013, Bolivia could be accepted as a contracting party again.

Colombia

The coca acreage in Colombia increased again in 2005, although in 2004 130,000 hectares of acreage were sprayed with herbicides. In 2004, the US-financed spray campaigns cost the equivalent of an estimated half a billion euros. During the same period, the authorities confiscated around 80 tons of pure cocaine and heroin with a black market value of around five billion euros. The country with the largest cocaine export in the world has considerable problems getting its drug crime under control.

Cocaine production in Colombia rose by 25 percent from 2016 to 2017 to around 2000 tons of cocaine. In 2017, nearly 70 percent of the world's cocaine came from Colombia.

Laos

The people of today's Laos have been familiar with opium since the 18th century. Knowledge of opium production came to Laos with immigrants in the early 19th century. Opium and other drugs are still socially recognized in Laos for various reasons. Opium production is an important source of income for farmers. Opium is important in the local barter trade and trading with it compensates for the sales proceeds from rice harvests that are too low.

In 1992 it was estimated that about two percent of the population were addicted to opium. 60 percent of the addicts were residents of the mountainous regions in the north of the country. In 1995, Laos was the third most important opium-producing country after Afghanistan and Myanmar.

The production, trade and use of opium have been criminal offenses since 1996. Even so, the number of drug addicts in 2001 was estimated at 58,000. In addition to opium, heroin, amphetamines and adhesives are increasingly being consumed. The government of Laos, in cooperation with the UNDP and non-governmental organizations, is trying to tackle the problem of drug crime and abuse. The focus is on offering opium producers an alternative source of income. At the same time, educational programs are being carried out in the affected regions.

Morocco

Morocco is the largest producer of cannabis and hashish , according to the UNODC . The cultivation of hemp takes place mainly in the Rif mountains in the north of the country such. B. in Nador. In 2003, hemp was grown in Morocco on an area of approximately 134,000 hectares. The acreage had decreased to 76,400 hectares by 2005. Cannabis production fell from 3,070 t (2003) to 1070 t (2005) in the same period. Around 800,000 people in Morocco make a living from growing cannabis, although it is officially banned. With the help of the EU, the government is trying to offer the farmers alternatives.

Mexico

Mexican President Felipe Calderón has declared the fight against organized drug crime in Mexico to be one of his most important goals for his term from 2006 to 2012. The armed conflict, known as the drug war in Mexico , which is carried out by police and military units against the drug cartels active in the drug trade, claimed around 200,000 and 250,000 deaths on all sides between 2006 and June 2018, and 26,000 corpses were possible (as of August 2019 ) cannot be identified.

The US authorities believe that the majority of the drugs smuggled into the US come from Mexico. Some of it, like marijuana and methamphetamine, is home-grown or manufactured in Mexico. Most importantly, Mexico is a transit country for cocaine from Colombia and other South American countries: an estimated 90% of all cocaine sold in the US is transferred through Mexico and smuggled into the US. The proceeds from drug smuggling in the USA are said to amount to between 18 and 39 billion dollars annually for the Mexican and Colombian drug cartels.

Myanmar

Myanmar is located in the so-called Golden Triangle , where the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) is grown and processed into heroin. The importance of Myanmar as a supplier for the global heroin market has declined noticeably as drug production has rebounded in Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban . However, Myanmar is a world leader in the production of amphetamines . The amphetamine is produced by the ton in jungle factories that are difficult to find and exported around the world, mainly via Thailand and China.

Peru

According to the national authority for the fight against drugs "DEVIDA" (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo y Vida sin Drogas), 110,000 tons of coca leaves were harvested in Peru in 2004. Peru's share of the global coca harvest (as of 2005) was in second place with 30%, behind Colombia with 54% and in front of Bolivia with 16%. About 85% of coca cultivation is for illegal production. A 2005 study by the Instituto Peruano de Economía y Política estimates the production potential of cocaine in Peru at almost 370 tons, which in the country itself would correspond to a market value of one billion US dollars. On the international markets in North America and Europe, the value of this amount is twenty times that. According to Nils Ericsson, Chairman of DEVIDA, only a fraction of this money remains with the around 50,000 families who live from coca cultivation. Most of them have to continue to live in poor conditions.

Legal position

→ See also: Legal aspects of cannabis

Germany

Narcotics Act

According to the Narcotics Act (BtMG) in Germany (Section 3 (1)), permission from the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices is required if narcotics:

- plant,

- produce,

- trade with them,

or without trading with them, they

- introduce,

- To run,

- submit,

- sell,

- otherwise bring into circulation,

- acquire

- or wants to produce exempt preparations (Section 2 Paragraph 1, No. 3 BtMG / Germany).

Handling narcotics without a permit is generally a criminal offense. There are exceptions to the licensing requirement according to Section 4 BtMG, for example for pharmacy operators or doctors. The mere consumption of narcotics is de jure not punishable in Germany, but can be interpreted by the law enforcement authorities as an initial suspicion of drug possession. In the case of dependency (Section 35 BtMG) or “if the guilt of the perpetrator is to be regarded as minor, there is no public interest in prosecution and the perpetrator only cultivates, produces, imports, exports, carries out, acquires, or acquires the narcotic drug for personal consumption in small quantities procured or possessed in any other way ”(§ 31a BtMG), a penalty can be waived.

Permission according to § 3 Abs. 2 BtMG

According to Section 3, Paragraph 1 of the BtMG, the cultivation, manufacture, trade, etc. of narcotics requires a license from the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. A license for the narcotics listed in Annex 1 can be granted for scientific or other purposes in the public interest in accordance with Section 3 (2) BtMG.

According to a judgment of the Federal Administrative Court (BVerwG May 19, 2005 - 3 C 17/04), treatment with cannabis in the context of multiple sclerosis can be therapeutically justified. The permission according to § 3 Abs. 2 BtMG must therefore be granted: According to the justification of the judges, a public interest is given if the project corresponds at least to a concern of the general public. One such concern is the medical care of the population, which, according to Section 5 (1) No. 6 BtMG, is also one of the purposes of the Narcotics Act. However, this supply is realized in the supply of individual individuals, e.g. B. a person with multiple sclerosis disease.

Offenses related to drug-related crime (narcotics offenses)

One form of drug-related crime is drug-related offenses that are directly related to the possession, sale, trafficking, etc. of drugs. Another form of drug-related crime is drug-related crime.

The criminal liability of narcotics offenses is based on the Narcotics Act . Sections 29–30b BtMG regulate a large number of criminal offenses which, for example, also relate to the unauthorized dispensing of narcotics by pharmacies and doctors and are therefore only marginally related to the term drug crime. The following explanations therefore do not claim to be a complete list of all criminal offenses of the BtMG, nor are any administrative offenses discussed!

Section 29 I No. 1 and No. 3 BtMG

The basic offenses of § 29 I No. 1 and No. 3 BtMG are of practical importance. According to this, anyone who cultivates, manufactures, trades in narcotics without trading, imports, exports, sells, surrenders, otherwise puts them on the market, acquires them or procures them in any other way is liable to prosecution (no. 1) or owns it without being in possession of a written permit for the acquisition at the same time (No. 3). Such crimes are punishable by imprisonment for up to five years or a fine.

The consumption itself is not punishable. In principle, however, it can be assumed that the person who consumed or consumed narcotics - which can also result from blood samples that the perpetrator had to hand in on the occasion of another crime, such as a drunk driving - was also in possession of these narcotics beforehand. When a consumption is established, there is usually an initial suspicion of possession of narcotic drugs, so that criminal proceedings are initiated.

Offenses with increased penalties

Based on these basic facts, a number of offenses are threatened with higher penalties. At first glance, the regulation described below appears comparatively confusing. However, it is fundamentally based on the principle that an increased risk also leads to an increased penalty. This increased risk can be based in particular on the fact that the perpetrator is acting commercially, the quantities exceed a certain limit or the perpetrators have formed a gang or on a combination of several aggravating factors.

With the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court (BVerfG) of September 18, 2006 (2 BvR 2126/05), the BGH's current interpretation of the term “trading” is compatible with the principle of certainty and is thus largely beyond discussion for the time being. According to this, the term trading (according to the Narcotics Act) includes “any self-serving activity aimed at the sale of narcotics” (cf. also NJW 2007, 1193). The BVerfG is based on a very broad interpretation of commercial activity. An act is completed even if the targeted sales of narcotics are not achieved. Self-interest exists if the offender's actions are "guided by the pursuit of profit or if he promises some other personal advantage that will put him in a better position, materially or immaterially" (cf. BGH decision of November 30, 2004, 3 StR 424 / 04). This also interprets selfishness very broadly. An intangible advantage must be "objectively measurable", i. H. recognizable to a third party.

A significantly increased penalty, namely imprisonment of one to fifteen years, is then imposed in accordance with Section 29 III BtMG in a particularly serious case. According to Section 29 III No. 1 BtMG, this is to be assumed in particular if the perpetrator in the cases under Section 29 I No. 1 is acting commercially. He acts commercially if he commits the above-mentioned acts in order to obtain a not only temporary source of income of some extent. This can also be the case, for example, if the perpetrator trades drugs in order to finance his own drug consumption. Legally, these acts are classified as offenses , which means that there is at least the possibility of a cessation of proceedings according to Sections 153, 153a of the Code of Criminal Procedure (StPO) under the aspect of the principle of opportunity . This opens up the possibility for courts and public prosecutors to discontinue the proceedings, for example due to minor fault, even if the evidence can be provided.

The same penalty as the offenses under Section 29 III, namely imprisonment between one and fifteen years, also have the offenses under Section 29a. But these are crimes . This means that a cessation of proceedings according to §§ 153, 153a StPO is not legally possible. If the evidence is to be provided, a penalty must be imposed. Section 29a provides, on the one hand, the dispensing of narcotic drugs by a person over the age of 21 to a person under the age of 18 (Section 29a I No. 1 BtMG) and, on the other hand, dealing with narcotics in not small quantities as well as the manufacture, dispensing and possession of narcotic drugs in not small quantities (§ 29a I No. 2 BtMG) under penalty. The boundaries between small and not small amounts naturally differ for the various narcotics. It is also not the total amount that is decisive, but the amount of the active ingredient contained therein. If necessary, this can be determined by means of expert reports.

An even higher custodial sentence threatens when committing the offenses of § 30 BtMG. This criminalizes the unauthorized import of narcotics in large quantities, the reckless cause of the death of a person through the sale of narcotics, the commercial inspection of Section 29a I No. 1 BtMG and the cultivation, production and trading of narcotics in a gang. For such acts, imprisonment between two and fifteen years is imposed.

With imprisonment of between five and fifteen years, in accordance with Section 30a BtMG, cultivating, manufacturing and trading narcotics in large quantities is punishable, and trading while carrying a weapon is a criminal offense. In the case of armed trafficking, it is a prerequisite that a significant amount of narcotics is traded and that a firearm or other dangerous object is carried. In the case of everyday objects that are objectively capable of causing physical injuries, the perpetrator's specific awareness of disposal must be examined very critically.

Reasons to mitigate punishment, waiver of punishment and refrain from bringing public charges

According to § 29 et seq. BtMG, anyone who only buys narcotics in small quantities for personal consumption , owns them, etc. According to §§ 29 V and 31a BtMG, however, the public prosecutor or the court can suspend or suspend the proceedings in these cases. refrain from punishment. However, there is no entitlement to this. Rather, the public prosecutor's offices and courts decide on a case-by-case basis. An unconditional cessation is usually not considered if the act has led to a threat to others.

According to Section 31 of the BtMG, information provided by the perpetrator on the involvement of other persons can have a mitigating effect if the act can be uncovered beyond his own contribution or if planned acts can be prevented. Successful education is required. Section 31 of the BtMG does not apply to mere efforts to provide information. Mitigation is excluded as soon as the court has opened the main proceedings. From this point on, information can only be considered as a general reason to mitigate the penalty.

With Section 37 of the Narcotics Act, the Public Prosecutor's Office also has the option of temporarily refraining from bringing an indictment if the offense was committed on the basis of narcotics addiction, no higher penalty than a prison sentence of up to two years is to be expected and the offender is undergoing treatment and its rehabilitation is to be expected. Under the same circumstances, once the charges have been brought, the court may suspend the proceedings with the consent of the public prosecutor. If the requirements mentioned are not met, the procedure is continued.

In addition, cessations of proceedings according to the general provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure or, in the case of young people and adolescents, according to the Youth Courts Act may also be considered.

According to a comparative law study by the Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law in the federal states, there is an unequal legal practice when proceedings are discontinued under Section 31a of the BtMG. In North Rhine-Westphalia, for example, application of Section 31a of the BtMG is only considered in exceptional cases in proceedings involving the handling of other illicit narcotics (heroin, cocaine and amphetamine, etc.). Because of the special health risks and the thought of bringing up young people and adolescents accused, recruitment because of a small amount is usually only possible subject to conditions within the meaning of Section 45 (2) JGG.

New Psychoactive Substances Act

The New Psychoactive Substances Act (NpSG) was passed on November 21, 2016 to close an existing loophole. The NpSG fundamentally prohibits trading in a new psychoactive substance, placing it on the market, manufacturing it, relocating it, acquiring it, owning it or administering it to another ( Section 3 (1) NpSG). In addition to the individual substance approach of the Narcotics Act, the NpSG contains a substance group regulation in order to be able to counter NPS legally more effectively.

The two groups of substances of NPS that are subject to the ban are listed in the annex to the law:

- Compounds derived from 2-phenylethylamine (i.e. amphetamine- related substances, including cathinones )

- Cannabinoid mimetics / synthetic cannabinoids (i.e. substances that mimic the effects of cannabis )

Procurement crime

The acquisitive directed either to obtaining drugs (see. Above definition) or to solicit cash or goods for which cash can be obtained for the purchase of drugs again turn. In addition to shoplifting , burglary in vehicles and company rooms is particularly important.

Austria and Switzerland

As in other countries, almost everything is punishable under the Addictive Substances Act. This includes: the acquisition, possession, placing on the market, importing or exporting, producing, surrendering or procuring narcotics. The consumption of narcotic drugs per se is not punishable in Austria. In Switzerland, according to Article 19a of the Narcotics Act , the consumption of narcotics is also a criminal offense. The New Psychoactive Substances Act (NPSG) in Austria has provided custodial sentences for traders from one to ten years since February 1, 2012.

Netherlands

The Netherlands had signed up to international treaties (including 1961, 1971, 1988). Therefore, contrary to what is generally assumed, almost all drugs are prohibited under the Dutch Narcotics Act (Opiumwet). In principle, the same acts are punishable in the Netherlands as in many other countries. This includes possession of many types of drugs. Only the sale of a maximum of 5 grams of cannabis in legal coffee shops is tolerated or not sanctioned. As in Germany and many other EU countries, drug use is exempt from punishment.

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic , possession of small amounts of drugs has been legal since 2010. The government had set caps on the various types of drugs. In August 2013, the Constitutional Court in Brno declared the existing regulation from 2010 to be invalid. The amount of permitted drug possession must be determined again by the courts in each individual case after the judgment.

Fight against drugs

As early as 1979, the German criminologist Arthur Kreuzer distinguished three basic strategies ( approaches ) in drug policy, which mainly related to the group of users of illegal drugs. According to Kreuzer, there were three different strategies:

- Social policy strategy (social approach) . This approach includes therapeutic, social and educational measures or all recommendations of prevention . It is not aimed at the supply side, but rather at the demand side with the aim of weakening it. Drug consumption is a task for society as a whole. Society must therefore create alternatives to drug use.

- Criminal policy or legalistic strategy (legal approach) . The strategy is directed against the availability of drugs. This approach is primarily driven by the law enforcement authorities and the judiciary.

- Liberal or anti-prohibitive strategy (liberal approach) . This approach is against the criminalization of drug users. The strategy rejects criminal action against the demand side and in many cases also against the supply side.

In today's German drug policy, there is heated debate among the political parties about the best strategy for dealing with drugs, especially cannabis. The party programs of the parties represented in the Bundestag contain different concepts for solving the drug problem. The parties' approaches are based on the following two approaches:

- The repressive approach that seeks to ban the cultivation, manufacture, distribution and possession of drugs. The repressive approach promotes a drug-free society and criminalizes many drugs.

- The accepting or progressive approach that assumes that a drug-free world is illusory and that the drugs concerned are consumed despite repression. It is necessary to operate harm reduction through various programs. According to this approach, the use of drugs in private should be allowed.

Whether the protection of the individual is better achieved through the repressive or progressive approach is particularly debatable in politics. Proponents and opponents ( war on drugs ) of drug legalization often argue with ideological points. There is currently no end in sight to the debate. Various scientific studies on the subject come to the conclusion that drug policy has no influence.

The drug policy of individual EU states must be seen today in the context of European and global drug policy. The member states of the European Union contribute to shaping the principles and measures in European drug policy and are of course obliged, like all member states, to implement them.

As members of the United Nations, all EU states have acceded to all international drug control treaties. The states have thus undertaken to implement the provisions of these conventions domestically and to forward the necessary information for monitoring to the UNDCP (drug control bodies of the United Nations).

complexity

In the fight against drugs, below political and moral method orientation (“social”, “legal”, “liberal”), efforts are made on the executive levels to work in a goal-oriented manner, because the task is so complex that possible solutions from a political and moral point of view are counterintuitive can appear. To this end, the complexity of the drug business with its various factors must be understood: A practically applied instrument for the representation of complex causal relationships is the fuzzy cognitive map (FCM, literally translated: "fuzzy cognitive map "). The "fuzzy" in FCM comes from the fact that the calculations that can be carried out with the help of the FCM can be derived from the mathematics of fuzzy sets , although the practical calculations then do not use fuzzy sets, but only easily manageable scalars. Rod Taber uses such an FCM to represent eleven factors in the drug business in the form of a Hasse diagram . (Rod Taber's FCM was depicted in Bart Kosko's book Fuzzy Thinking .)

In the illustration described below, the goal is to reduce drug availability. We are looking for the most suitable methods to achieve the goal. To do this, the importance of the drug market factors must be determined. An impact matrix can be derived from Rod Taber's FCM: In the left column the factors are listed as impact factors, in the top line the same factors are lined up as objects of impact. Then the table shows how the factors in the left column affect the factors in the top row. In the present case, a trinary logic with three scalars is used: positive effect (strengthening or +1), negative effect (weakening or −1) and no significant effect (empty field or 0):

Represented in such a matrix , the interactions can also be calculated. This makes it possible to discuss other causal relationships and to simulate their effects, because the content of the FCM is only one of several possible hypotheses.

International

Germany

The preventive and repressive measures in Germany are laid down in the Federal Government's annual Drugs and Addiction Action Plan. Currently, the measures are based on the following four pillars of the action plan:

- the drug prevention (eg., by the Federal Center for Health Education , Glass School )

- the treatment of addictions (e.g. drug substitution , drug therapy , drug counseling )

- survival aids (e.g. through drug consumption rooms , emergency aid) for heavily dependent people

- the supply reduction and repressive measures (e.g. by law enforcement authorities )

This also includes a controversial model experiment for the heroin-assisted treatment of so-called original substance substitution in several federal states and cities in Germany.

EU

In Europe, drug prevention measures are aimed at the general population (universal prevention), the most vulnerable groups (selective prevention) or individuals (indicated prevention). The most advanced models of universal prevention are student programs that are relatively scientifically sound as to content and implementation. Universal prevention outside of school also has considerable potential, but this type of prevention is currently only implemented in a few countries.

On November 12, 2004, the EU stipulated in a framework resolution to combat drug trafficking , within which framework the maximum penalties to be provided by law in the member states for drug trafficking offenses and for the unauthorized handling of so-called raw materials that are to be used for illegal drug production must be at least :

- The trafficking in drugs, which relates to a small amount or not particularly dangerous drugs, should be punished with a maximum of imprisonment of at least one to three years.

- Drug trafficking in large quantities or with particularly dangerous drugs or trafficking in drugs that could cause serious damage to health in several people should be threatened with a maximum of imprisonment of at least five to ten years.

- The maximum imprisonment sentence should be at least ten years if such acts are committed by a criminal gang.

- In the case of serious cases of illegal handling of raw materials used in the manufacture of drugs, a maximum sentence of at least five to ten years' imprisonment should apply.

- The decision also contains requirements for the definition of the individual drug offenses, the possibility of mitigating sentences if the perpetrator provides the law enforcement authorities with relevant information, rules on the liability of legal persons in whose favor the offense occurs, and finally provisions on the jurisdiction of the Member States.

The German Narcotics Act already takes the EU guidelines into account.

Further measures by the European Union were regulated in the EU Drugs Action Plan (2013–2016). The guidelines of the plan concentrate on five axes of action: coordination, demand reduction, supply reduction, international cooperation as well as information, research and evaluation.

In 2012, the European Council also adopted the EU Drugs Strategy for the period 2013-2020.

China

In China , on August 22, 2006, a law to combat drug crime was placed on the agenda of the Standing Committee of the Chinese National People's Congress. This law is intended to prevent the expansion of drug-related crime, define drug crimes precisely, regulate drug withdrawal measures and determine whether the use of drugs is prosecuted. According to the new law, combating drugs will in future be a task for society as a whole.

In 2005, there were 1.16 million drug addicts in China, according to official figures. 700,000 of them are said to use heroin. Based on these numbers, addicts cost RMB 40 billion yuan annually.

United States

Many international conferences were convened on the initiative of the USA at the beginning of the 20th century . The first US regulations emerged mainly against the background of moral-political motives. The Harrison Narcotic Act in 1914 initially prohibited the free sale of cocaine and opium in the USA. Three years later, the abstinence movement implemented prohibition in the United States . For several decades, the United States has been accused of trying to regulate its political and tactical goals through international drug treaties.

Drug crime has increased in the US since the 1960s. According to the US Public Health Service in 2004, drug control costs the US around $ 600 per second. In the same year, according to the FBI, 1,511,000 people were arrested for drug offenses in the United States. Almost half of all arrests (46.5%) were related to cannabis possession. Drug crime employs around 400,000 police officers in the United States alone. The arrested perpetrators are a heavy burden on the US courts. They take up half the total time of all US lawsuits.

For the first time in US history, following a previous referendum, the state of Colorado officially approved the sale of marijuana up to one ounce (around 28 grams) for citizens over the age of 21 on January 1, 2014 . Supplementary rules continue to prohibit sales to minors, use on the street, and take cannabis into other states .

Other countries

In some countries, drug trafficking or possession (above a certain amount) is a particularly serious criminal offense. This drug crime is punishable by death in the States. The reasons given for justifying the death penalty are deterrence and the direct protection of society through the removal of the perpetrator. The death penalty for certain drug offenses applies e.g. B. in the countries Singapore , Philippines , Saudi Arabia , Thailand . In Thailand alone, drug dealers were sentenced to death over 30 in July 2001. In Saudi Arabia, 63 people were executed for drug offenses in 2015.

In the Philippines , when he was elected in the summer of 2016 , President Duterte went even further and called on its citizens to kill drug dealers and users, resulting in hundreds of victims in a short period of time.

Drugs and traffic

The Road Traffic Act (StVG), the Driving License Ordinance (FEV) and the Criminal Code (StGB) limit drug consumption in Germany.

- Anyone who drives a vehicle in traffic in Germany even though they are unable to drive the vehicle safely due to the consumption of alcoholic beverages or other intoxicating substances is liable to prosecution under the Criminal Code (Section 316 StGB).

- An administrative offense according to Section 24a (2) of the Road Traffic Act is anyone who drives a motor vehicle under the effects of an intoxicating substance (cannabis, heroin, morphine, cocaine, amphetamines, designer amphetamines) listed in the Annex to the Road Traffic Act.

- Is unsuitable for driving motor vehicles for the driving license authority according to Annex 4, number 9 of the Driving License Ordinance (FEV),

- who consumes narcotics (other than cannabis products) or is dependent on them (i.e. without having driven a vehicle).

- who takes cannabis regularly or, with occasional use, cannot separate consumption and driving or who also use alcohol or other psychoactive substances (multiple consumption).

The control authorities use rapid drug tests for traffic controls . If the rapid drug test is positive, they will order blood and / or urine samples . A hair sample can also be taken. According to the principle of proportionality and a strict individual examination, the use of emetics is only possible for serious crimes.

Similar regulations apply in the other European countries.

Legal drug infrastructure

Cannabis products can be sold under certain conditions in tolerated sales outlets (the so-called coffee shops) in the Netherlands . These sales outlets are non-alcoholic restaurants where the sale of a small amount of cannabis to (Dutch) customers with so-called “wietpas” (grass pass) is tolerated, although the sale of cannabis is generally a criminal offense. Legal coffee shop operators in the Netherlands receive a permit with instructions from the local municipality. Because of the coffee shops, drug tourism from Germany to the Netherlands had increased since 1976.

Sales outlets that legally sell other so-called “ soft drugs ” or hallucinogenic substances under Dutch law , e.g. B. psychoactive mushrooms, cacti containing mescaline, aphrodisiacs and energizers are called smart shops . Shops or stores that sell drug accessories and products typical of the scene are called head shops . If mainly accessories for cultivation are offered, it is a grow shop .

However, drug use without punishment is limited across Europe by traffic law standards.

See also

- drug

- European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction

- Juvenile delinquency

- Police advice center

literature

- Harald Hans Körner : Narcotics Act (BtMG), Medicines Act. 6th edition, Beck Juristischer Verlag, 2007, ISBN 3-406-55080-0 .

- Jan Wriedt: From the beginnings of drug legislation to the Narcotics Act January 1, 1972. Lang-Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-631-54314-X .

- Alfred W. McCoy: The CIA and Heroin. World politics through drug trafficking. Zweiausendeins-Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-86150-608-4 .

- Detlef Briesen: Drug Consumption and Drug Policy in Germany and the USA. A historical comparison. Campus Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-593-37857-4 .

- Andreas Paul: Drug users in juvenile criminal proceedings. Lit-Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8826-6 .

- Martin Krause: Drugs and a driver's license. Criminal defense and case law overview. Books on Demand Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-8311-4804-X .

- Martin Lutterjahn: Drugs in travel destinations . Law and reality. Reise Know-how Verlag Rump, 2003, ISBN 3-8317-1174-7 .

- Wolfgang Schmidbauer , Jürgen vom Scheidt: Handbook of intoxicating drugs. 4th edition, 1999, ISBN 3-596-13980-5 .

- Norbert Thomas, Peter Loos, Knuth Stroh: Drug crime. Boorberg, 1996, ISBN 3-415-00946-7 .

- Kornelie Schütz-Scheifele: Drug crime and its fight. Schäuble, 1991, ISBN 3-87718-111-2 .

- Alexander Niemetz: The Cocaine Mafia. Bertelsmann, 1990.

- Regine Schönenberg: International drug trade and social transformation. German University Press , ISBN 3-8244-4406-2 .

Web links

statistics

- Federal Drug Crime Situation Report 2018 (PDF; 1 MB)

- Map of Germany - drug kitchens and hemp plantations

- Criminal statistics Austria

- Crime Statistics Switzerland

- UN Office on Drugs and Crime

- European Drugs Report 2019 (PDF)

- Drug-related crime England ( Memento of March 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Drug-related crime USA ( Memento of December 11, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Drug-related crime Australia (English)

- Drugs, war and drug war (Colombia) (PDF; 749 kB)

- Drugs White Paper China ( Memento of March 13, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

activities

- Beckley Foundation (BFDPP) Reducing Drug Crime - Report 5 ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 315 kB)

Legal

- Judgment of the BVerfGE 90, 145 - Cannabis ( Memento of February 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Mustafa Temmuz Oglakcioglu: death on prescription - considerations on the attribution of facts in the case of medically enabled consumption of narcotics hrr-strafrecht.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ EU Drugs Action Plan (2005–2008) , p. 11, point 25.1

- ↑ Press release of the EU Drugs Monitoring Center from June 25, 2007 (PDF; 79 kB)

- ↑ Drugs and Crime - Elaboration of a definition of drug-related crime, European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction , 2007 (PDF; 86 kB), accessed on November 9, 2010.

- ↑ a b c PKS , Federal Republic of Germany, 2004.

- ↑ BKA, Federal Situation Report on Narcotics Crime 2011 . Wiesbaden 2012, p. 6, FN 1 to 3.

- ↑ Henning Schmidt-Semisch: Smoking weed is not enough or: Radical alternatives in drug policy. DrugsGenussKultur, July 13, 2002, accessed on March 31, 2008 : “And finally, about the fact that people have the right to take the substances they want to use. It is about a generally understood right to enjoyment and also a right to be intoxicated . "

- ↑ Schmidtbauer, v. Scheidt: Handbook of intoxicating drugs. 4th edition, 1999, p. 635.

- ^ Agreement between Eve and Rave

- ^ Agreement 1931 , PDF ( Memento of August 29, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Single Convention ( Memento from May 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Thomas Feltes , lecture at the XII. Mosbacher Symposium of the Society for Toxicological and Forensic Chemistry on April 26, 2001 Archive link ( Memento from June 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Review of the title “Drugs and Police” ( memento from February 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) by Jürgen Stock, Artur Kreuzer by Rudolf Egg in the magazine Sucht, volume 44/1998, issue No. 2, p. 136.

- ↑ BKA: Narcotics crime, Federal Situation Report 2018, p. 3.

- ↑ BKA: Drug crime, Federal Situation Report 2018

- ↑ Drug affinity of young people in the Federal Republic of Germany. (PDF) Drogenbeauftragte.de, BZgA, p. 55 ff.

- ↑ WHO study (PDF)

- ↑ ESPAD study (PDF)

- ^ BND-Internationaler Drug Trafficking ( Memento of July 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ UN Action Plan against Drugs and Money Laundering , Berliner Zeitung

- ↑ Borzou Daragahi: 'Colombia of Europe': How tiny Albania became the continent's drug trafficking headquarters. In: Independent.co.uk. January 27, 2019.

- ↑ NZZ Online ( Memento from August 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Drugs and Addiction Report of the German Federal Government, May 2006

- ↑ Deutsche Welle: Opium production in Afghanistan reaches record high on November 15, 2017, accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ↑ Bettina Schorr: The drug policy in Bolivia and the American war on drugs , p. 16 ff., University of Cologne ( PDF ( Memento from March 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Bolivia's struggle for the right to intoxication , Derstandard.at of June 29, 2011

- ↑ Jan-Uwe Ronneburger: Columbia and the Curse of White Gold ( Memento from February 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), Netzeitung May 15, 2005

- ↑ Deutschlandfunknova.de: Colombia - Coke production at its peak on June 26, 2019, accessed on March 21, 2020.

- ^ Morocco , Federal Agency for Civic Education

- ↑ David Agren: Mexico's monthly murder rate reaches 20-year high . In: The Guardian . June 21, 2017, ISSN 0261-3077 ( theguardian.com [accessed August 9, 2019]).

- ↑ José de Córdoba, Juan Montes: 'It's a Crisis of Civilization in Mexico.' 250,000 dead. 37,400 Missing. In: Wall Street Journal . November 14, 2018, ISSN 0099-9660 ( wsj.com [accessed May 27, 2020]).

- ^ Mexico: The Other Disappeared. January 15, 2019, accessed on May 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Daniela Diegelmann: Peru on the way to becoming a drug state ?, KAS PDF ( Memento from November 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ BVerfG, 2 BvR 2126/05 of September 18, 2006 , accessed on January 31, 2011

- ↑ Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law: Drug Consumption and Law Enforcement Practice, A comparative law study on the legal reality of the application of § 31a BtMG and other opportunity regulations to drug abuse offenses ( Memento of the original from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet tested. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed August 30, 2009

- ↑ Joint circular of the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of the Interior, guidelines for the application of Section 31a, Paragraph 1 of the Narcotics Act of August 13, 2007 , accessed on August 30, 2009

- ↑ Text of the New Psychoactive Substances Act (NpSG) , Federal Law Gazette I p. 2615

- ↑ bmg.bund.de ( Memento from May 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ; PDF)

- ^ Radio Prague ( Memento from December 16, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Constitutional Court collects regulations for personal use of drugs ( memento of September 23, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Radio.cz, accessed on August 3, 2013

- ↑ Drug possession in the Czech Republic - the court overturns the regulations for personal use ( memento of August 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Tagesschau.de, accessed on August 3, 2013.

- ↑ Benjoe A. Juliano, Wylis Bandler: Tracing Chains-of-Thought (Fuzzy Methods in Cognitive Diagnosis) , Physica-Verlag Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-7908-0922-5

- ↑ Rod Taber: Knowledge Processing with Fuzzy Cognitive Maps , Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 2, no. 1, 83–87, 1991 (Hasse diagram as PDF ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Bart Kosko: Fuzzy Logisch (A New Way of Thinking) , 1993/1995, ISBN 3-612-26161-4 (English: ISBN 0-7868-8021-X , Chapter 12: Adaptive Fuzzy Systems)

- ↑ FCM calculations: http://www.ochoadeaspuru.com/fuzcogmap/index.php

- ↑ A simple example of using cognitive maps for simulations can be found in a book by William R. Taylor: Lethal American Confusion (How Bush and the Pacifists Each Failed in the War on Terrorism) , 2006, ISBN 0-595-40655-6 . In the book, the wars of the USA in Afghanistan and Iraq are analyzed with a quintary logic (−1; −0.5; 0; +0.5; +1).

- ↑ Drug Prevention Europe

- ↑ Addiction / Drug Report 2005 . (PDF)

- ↑ EU Drugs Action Plan (2013-2016)

- ↑ EU Drugs Strategy 2013–2020

- ↑ China steps up the fight against drug-related crime , China Economic Net, August 24, 2006

- ^ Josef-Thomas Göller: The war in one's own country , The Parliament (Bundestag), 2005.

- ↑ Legalization of Cannabis - Colorado Starts Free Sales of Marijuana , Spiegel-Online January 1, 2014, accessed January 2, 2014.

- ↑ Jan Bösche: After marijuana legalization, Colorado celebrates cannabis , Tagesschau.de from January 2, 2013, accessed on January 2, 2014.

- ^ Death penalty Thailand .

- ↑ theguardian.com:Saudi Arabia: beheadings reach highest level in two decade

- ↑ Jonathan Kaiman: "Meet the Nightcrawlers of Manila: A night on the front lines of the Philippines' war on drugs," LA Times, August 26, 2016