Narcotics Act (Germany)

| Basic data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Law on the traffic in narcotics |

| Short title: | Narcotics Act |

| Previous title: | Opium Act |

| Abbreviation: | BtMG |

| Type: | Federal law |

| Scope: | Federal Republic of Germany |

| Legal matter: | Special administrative law , ancillary criminal law |

| References : | 2121-6-24 |

| Original version from: | December 10, 1929 (RGBl. I p. 215) |

| Entry into force on: | January 1, 1930 |

| New announcement from: | March 1, 1994 ( BGBl. I p. 358 ) |

| Last revision from: | July 28, 1981 ( BGBl. I p. 681 , ber.p. 1187 ) |

| Entry into force of the new version on: |

predominantly January 1, 1982 |

| Last change by: |

Art. 1 Regulation of 10 July 2020 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 1691 ) |

| Effective date of the last change: |

July 17, 2020 (Art. 2 of July 10, 2020) |

| Weblink: | Text of the BtMG |

| Please note the note on the applicable legal version. | |

The Narcotics Act (BtMG), formerly the Opium Act ( see below ), is a German federal law that regulates the general handling of narcotics .

The substances and preparations covered by the Narcotics Act can be found in Annexes I to III of the Act (Section 1 (1) BtMG):

- Annex I records the non- marketable narcotics (trading and distribution prohibited, e.g. LSD ),

- Annex II the marketable but not prescription narcotics (trade permitted, sale prohibited, such as raw materials such as coca leaves ) and

- Annex III the marketable and prescription narcotics (delivery according to BtMVV , e.g. morphine ).

The systems are each structured in three columns. Column 1 contains the international non-proprietary names (INN) of the World Health Organization ( e.g. amfetamine ), column 2 other unprotected substance names such as short names or common names ( e.g. amphetamine) and column 3 the chemical substance name ( e.g. ( RS ) -1-phenylpropan-2-ylazane) .

The list of narcotics under the Narcotics Act gives a complete overview of the substances recorded .

content

The BtMG is divided into eight sections

- Definitions

- Permission and authorization procedure

- Obligations in narcotics traffic

- monitoring

- Regulations for authorities

- Criminal offenses and administrative offenses

- Narcotics-dependent offenders

- Transitional and final provisions

Offense

Narcotics within the meaning of the BtMG and drugs are not to be equated. Alcohol , nicotine and caffeine are not recorded by the BtMG because they are not included in the systems. They are therefore legal drugs in Germany. But other intoxicating substances from various plants ( e.g. thorn apples and angel's trumpets ) as well as from mushrooms such as the fly agaric are not subject to the BtMG.

The provisions of the law regulate the manufacture, placing on the market , import and export of narcotic drugs in accordance with Annexes I, II and III. These activities require a permit that can be issued by the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Section 3 BtMG). Furthermore, the operation of drug consumption rooms are regulated (Section 10a BtMG), the destruction of narcotics and the documentation of traffic.

The Narcotics Act is a consequence of Germany's obligation to restrict the availability of some drugs in accordance with the provisions of the Convention, resulting from the ratification of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotics and other similar agreements .

The substances according to Annex I (illegal drugs) are subject to prohibition , the possession and acquisition of which is only possible with a special permit from the BfArM for scientific purposes or is accepted by a competent body for investigation or destruction. The substances listed in the appendices are so-called res extra commercium , in German non-tradable items . If they are imported into the federal territory, only the state has the right to exercise possession of these substances by means of seizure or confiscation.

Basically, the Narcotics Act belongs to the category of administrative laws, since the regulatory subject is the traffic of narcotics. However, due to the frequently applied criminal provisions in §§ 29–30a BtMG, it is also one of the most important laws in the area of ancillary criminal law .

For the import and export of the raw materials of many drugs (especially synthetic drugs such as amphetamine ) applies the precursor control law .

history

The Narcotics Act is the immediate successor to the Opium Act of 10 December 1929 enacted in the Weimar Republic ( RGBl. I p. 215). After the reformulation of the short title and extensive changes in content through the law of December 22, 1971 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 2092 ), a new publication ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 1 ) was issued on January 10, 1972 . The current version of the BtMG dates to July 28, 1981 ( BGBl. I p. 681 ); the wording of which was last published on March 1, 1994 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 358 ).

Hazard potential

The basic consideration of the Narcotics Act is the determination

- an addictive potential as a social impairment of a person in connection with

- an irreversible (irreversible) impairment to health or damage to the person's body (somatic or psychosomatic damage)

through single, repeated or continuous consumption of narcotics. All pharmaceuticals that are expected to cause such irreversible damage are or will be subject to the restrictions of the Narcotics Act. This also includes new designer drugs. In addition, there is an additional risk from the medically inappropriate preparation and administration of narcotics. Furthermore, the consumption of narcotics mobilizes a potential risk for third parties if the addict does his or her actions

- at work

- in traffic

- when driving vehicles

- in parental duties

can no longer control himself.

From the Opium Act to the Narcotics Act

Until the mid-1960s, drug policy was an extremely small and socially neglected policy area in relation to other areas of politics. Probably mainly due to the small number of socially conspicuous drug users, the Opium Act remained largely a paper law without an acute reality of persecution. The number of people convicted on the basis of the Opium Act was correspondingly low. At the beginning of the sixties of the 20th century this number was between 100 and 150 per year, i.e. two to three convictions per week in the whole of the Federal Republic of Germany.

At the end of the sixties the importance of drug and especially cannabis policy changed suddenly. This happened against the background of international development (international agreements) and above all the perceived "youth drug problem" in the USA. In Germany, following the lurid example in the United States of America, from the end of the 1960s the press gave the impression of a huge “hashish and drug wave” threatening to overwhelm the country. At the same time the image was mapped out a dramatic social problem in public opinion, which was also associated with the probably most important domestic political event of the time, namely the mainly student-supported protest movement that during the grand coalition of CDU / CSU and SPD of 1966 to 1969 as " Extra-Parliamentary Opposition (APO)" formed.

At the international level, the Federal Republic of Germany has acceded to a number of United Nations (UN) conventions on drug policy . These are the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of March 30, 1961 on Narcotic Drugs in the version of the Protocol of March 25, 1972 amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 (so-called Single Convention) and the Convention of February 21 1971 on Psychotropic Substances ( Convention on Psychotropic Substances ).

Against this background, in December 1971 the legislature ( German Bundestag and Bundesrat ) passed the Opium Act of December 10, 1929, which primarily regulated the administrative control of the medical supply of the population with opium, morphine and other narcotics, by means of a new "Act on the Traffic with narcotics (Narcotics Act, BtMG) ”. The new law of December 22, 1971, which was re-announced on January 10, 1972 after editorial changes, is based on an abstract typological classification of offenders, so that according to the legislature's view, each type of offender can be assigned a level of sanction, with the maximum penalty of three was increased to ten years.

The legislature authorized in § 1 para. 2 to 6 BtMG the federal government ( executive ) by legal ordinance to insinuate other substances to narcotics laws. The fact that not only the legislature but also a legislator of the executive can create criminal offenses that can be punished with long prison sentences (since December 25, 1971 up to ten years, since January 1, 1982 even maximum sentences of up to 15 years) , has repeatedly triggered heated and controversial debates among constitutional and criminal lawyers in recent years. The compatibility of the penal provisions of the Narcotics Act with the Basic Law is also controversial because, on the one hand, restrictions on fundamental rights may only take place in strict compliance with the proportionality requirement and, on the other hand, the criminally enforced drug prohibition hardly seems suitable to achieve the legislative goal (to prevent the availability of the substances listed in the annexes).

With the law on the reorganization of the narcotics law of July 28, 1981 ( Federal Law Gazette I, p. 681 ), which came into force on January 1, 1982, the upper penalty limit was increased from 10 to 15 years' imprisonment not only for particularly serious cases but also changed the definition of narcotics. In Section 1 (1) of the BtMG, the scope of the law was limited to the substances and preparations listed in Annexes I to III. Narcotics within the meaning of the law are only the substances and preparations named in Annexes I to III (positive list). The substances and preparations listed in Annexes I to III are part of the law.

"Cannabis Decision"

On March 9, 1994, the so-called cannabis decision of the Federal Constitutional Court was issued , according to which criminal proceedings can be discontinued at the discretion of the law enforcement authorities in the event of minor violations of the BtMG through the import, acquisition or possession of small quantities of cannabis for personal consumption , regulated below in Section 31a BtMG. In practice, this is handled very differently in different federal states, since in particular it is not uniformly stipulated what a “ small amount ” is.

Section 30c BtMG (property fine)

Since § 30c BtMG refers to § 43a of the Criminal Code (StGB) and the Federal Constitutional Court in its judgment of March 20, 2002 declared the property fine and thus § 43a StGB to be incompatible with Art. 103 (2) GG and null and void, the result is also § 30c BtMG not applicable.

Legal relationships

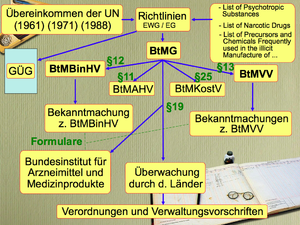

There are four ordinances in the context of the BtMG:

- Narcotics Prescription Ordinance (BtMVV)

- Internal Narcotics Trade Ordinance (BtMBinHV)

- Narcotics Foreign Trade Ordinance (BtMAHV)

- Narcotics Cost Ordinance (BtMKostV)

Thematically related are both the legal regulations on basic materials and drugs (AMG). In July 2014, the ECJ ruled that substances and preparations used for intoxication that are not classified as narcotic drugs are not to be regarded as medicinal products, and that the manufacture and marketing for this purpose cannot therefore be prohibited under the Medicines Act. The subject of the judgment were so-called " herbal mixtures ", which contained synthetic cannabinoids . The extent to which this ruling is applicable to other intoxicating substances that are not subject to the BtMG is a matter of dispute. BtMG and AMG have been supplemented by the New Psychoactive Substances Act (NpSG) since November 2016 , which criminalizes trading in the synthetic cannabinoids in question, as well as phenylethylamines .

Narcotics in medicine

The Narcotics Act stipulates which drugs are listed as narcotic drugs in Germany and are subject to strict regulations due to their risk potential. The substances and preparations that fall under the group of narcotics in this country are listed in the annexes to the law. Many of them are used in the medical field, e.g. B. in chronic severe pain, advanced cancer diseases, AIDS diseases and after operations.

Destruction of narcotics

The destruction of narcotics is regulated in § 16 BtMG. Accordingly, the owner of narcotic drugs that are no longer marketable must destroy them at his own expense and in the presence of two witnesses. The elimination must be carried out in such a way that even partial recovery of the funds is impossible. For the traceability of this destruction, the Narcotics Act requires a record that the owner must keep for three years.

Disposal of narcotics

In principle, it must be ensured that no one is harmed by accidental contact. Disposal takes place in the residual or household waste. For this purpose, solid dosage forms such as tablets, coated tablets, granules, capsules or suppositories are crushed by trituration. Capsules must be opened beforehand. Active ingredient patches are stuck together and cut into small pieces so that individual patches can no longer stick. Liquid anesthetics such as the contents of ampoules or drops can be absorbed in cellulose and disposed of in this form according to waste code 180104. There is an exception if a different disposal method is provided according to the package insert.

Swiss and Austria

The Swiss Narcotics Act is abbreviated to BetmG. In Austria the drug law exists .

literature

- Hügel, Junge, Lander, Winkler: German narcotics law. Comment. 8th edition. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart Status: March 2010, ISBN 978-3-8047-2523-2 (loose-leaf collection).

- Harald Hans Körner , Jörn Patzak, Mathias Volkmer: Narcotics Act. Beck'scher Short Comment No. 37, Verlag CH Beck, 7th edition, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62465-0 .

- New version of the Narcotics Act. 2001, ISBN 3-930442-06-X .

- Patzak, Jörn : Narcotics law . 2nd Edition. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61397-5 .

- Bernhard van Treeck: Drugs and Addiction Lexicon. Lexikon-Imprint-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89602-542-2 .

- Bernhard van Treeck: The great cannabis lexicon - everything about the useful plant hemp. Lexikon-Imprint-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89602-268-7 .

- Bernhard van Treeck: Drugs. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-89602-420-5 .

- Benjamin Fässler: Drugs between domination and glory. Nachtschatten-Verlag, Solothurn 1997, ISBN 3-03788-138-0 .

to the history of the same :

- Werner Pieper (Ed.): Nazis On Speed - Drugs in the 3rd Reich. Löhrbach 2002, Volume 1: ISBN 3-930442-53-1 , Volume 2: ISBN 3-930442-54-X .

See also

Web links

- Text and amendments to the Narcotics Act

- Country profile Germany of the "European Monitoring Center on Drugs and Drug Addiction"

Individual evidence

- ↑ Social Guide South Tyrol

- ↑ Drug distribution and problem perception (PDF; 745 kB)

- ↑ Drugs: Risk of alcohol and tobacco underestimated

- ↑ Drug use in the workplace (PDF; 1.6 MB)

- ↑ accepting drug work ( Memento from December 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Drug use in front of children and adolescents

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of March 20, 2002, Az. 2 BvR 794/95, BVerfGE 105, 135 - property penalty .

- ↑ "Accordingly, the term medicinal product in Art. 1 No. 2 letter b of Directive 2001/83 is to be interpreted as meaning that it does not cover substances whose effects are limited to simply influencing the physiological functions without being suitable, to be directly or indirectly beneficial to human health. ” CURIA - Documents

- ^ Kügel, Müller, Blattner: Medicines Act, Commentary ; 2nd edition 2016, Verlag CH Beck, Rn. 86, para. 99

- ↑ Andrea Rosenfeldt: Narcotics criminal law: Patzak u. a. discuss the ECJ judgment of July 10, 2014 , in: Jurion , August 19, 2014 (accessed August 28, 2017).

- ↑ Jörn Patzak : Reference to a critical contribution to the judgment of the ECJ , in: beck-community, August 20, 2014 (accessed August 28, 2017).

- ^ Uwe Hellmann : Commercial criminal law . Kohlhammer Verlag , October 30, 2018, ISBN 978-3-17-031444-3 , p. 250.

- ^ Waste manager medicine: Narcotics Act. In: Waste Manager Medicine. Retrieved March 18, 2020 (d).

- ↑ Waste manager medicine: Destruction of narcotics. In: Waste Manager Medicine. March 18, 2020, accessed on March 18, 2020 (d).

- ↑ Destruction of narcotics. In: https://umweltschutz.charite.de . Charité, accessed on March 18, 2020 (d).