Pitjantjatjara

Pitjantjatjara Pronunciation : [ ˈpɪcaɲcacaɾa ] is the name of a tribe of the Aborigines in Central Australia and their language. They are close relatives of the Yankunytjatjara and the Ngaanyatjarra as well as the Ghyeisyriieue . Their languages are largely mutually understandable as they are all variants of the Western Desert language group .

They call themselves anangu . The land of the Pitjantjatjara is mainly in the northwest of South Australia , across the border to the Northern Territory south of Lake Amadeus , and it also stretches a little into Western Australia . The land is inseparable and important to their identity, and each part is rich in stories and meaning to the Anangu.

They have largely given up their nomadic hunter-gatherer existence, but managed to maintain their language and culture despite the growing influence of Australian society. Today about 4,000 Pitjantjatjara still live in their traditional land, spread over small communities and farms.

The word Pitjantjatjara is pronounced one syllable less when speaking at a normal speed , i.e. Pitjantjara . All syllables are pronounced in slow, careful language.

history

After several sometimes fatal encounters with European dingo hunters and settlers, 73,000 square kilometers of land in northwestern South Australia were allocated to them in 1921.

Extended droughts in the 1920s and from 1956 to 1965 in the Great Victoria Desert and in the Gibson Desert meant that many Pitjantjatjara and their traditional west living relatives, the Ngaanyatjarra, east toward the railway line between Adelaide and Alice Springs on the Search for food and water and mingled with the easternmost group, the Yankunytjatjara.

The conflicts with the whites continued. Dr. Charles Duguid fought for their protection, trying to give them a chance to slowly adjust to the rapidly changing realities. As a result, the government of South Australia eventually supported the Presbyterian Church's plan to establish a mission in Ernabella on the Musgrave Ranges as a safe haven.

In the early 1950s, many Anangu were forced to leave their homeland as nuclear weapons tests were carried out by the British in this area of Maralinga . A large number of the Anangu were subsequently contaminated by the nuclear fallout from the nuclear tests and may have later died from it.

After four years of campaigning and negotiations with government and mining companies for land rights and the native title , the Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act was passed on March 19, 1981, granting them the property rights to more than 103,000 square kilometers of land in the northwest corner of South Australia. The Local Government Area Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara was founded there.

The Maralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act of 1984 guaranteed property rights to an area of 80,764 square kilometers as far as Maralinga Tjarutja . In 1985 the McClelland Royal Commission dealt with the consequences of British nuclear tests. The Mamungari Conservation Park was transferred to Maralinga Tjarutja in 2004.

Recognition of holy places

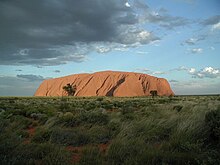

The holy places of Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa were spiritually and ceremonially very important to the Anangu: There are more than 40 named holy places and 11 different songlines from the dreamtime , which they call Tjukurpa. Some of these songlines lead to the seas in all directions.

However, Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are barely in the Northern Territory and thus separated from the land of the Pitjantjatjara in South Australia; they have become a major tourist attraction and eventually a national park. In 1979 the Central Land Council claimed Ulu -u-Kata-Tju Nationalparka National Park , at that time still called Ayers Rock-Mt.-Olga National Park, and some of the adjacent empty crown country, but met with fierce resistance from the government of the Northern Territory.

After eight years of lobbying by the land's traditional owners, Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced on November 11, 1983 that the federal government was planning to return the inalienable rights to them. He also agreed with the 10 main points the Anangu had called for leasing the national park to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service : In the joint management, the Anangu would have a majority on the board. This was finally granted in 1985, but the government failed to keep two promises: the leasing agreement was fixed for 99 years instead of 50 years and it was still allowed that tourists can climb Uluṟu, which is a desecration of one of their important sanctuaries. The park management has issued notices with the request not to climb the rock, but has no authority to enforce it.

The joint management of the 13.25 square kilometer world heritage has used the Anangu and millions of visitors have been able to enter the park.

Larger communities

See the WARU Community Directory for a complete list.

- South Australia

-

Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara , including:

- Ernabella , now called Pukatja

- Amata

- Kalka

- Pipalyatjara

- Yalata

- Oak Valley

-

Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara , including:

- In the Northern Territory

The language

| Pitjantjatjara | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Northwest South Australia | |

| speaker | 2,600 | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -2 |

out |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

pjt |

|

Special peculiarities of the Pitjantjatjara language are the ending -pa for words that normally end with a consonant, the missing y at the beginning of many words and the use of the word pitjantja for go or come. The name Pitjantjatjara is derived from the word pitjantja , a form of the verb “to go”, which with the comitative suffix -tjara means something like “ pitjantja to have”, ie the “way” pitjantja uses for “to go”. This distinguishes them from their neighbors, the Yankunytjatjara, who use yankunytja for the same meaning. The same naming applies to the Ngaanyatjarra and Ngaatjatjarra , but here the languages are delimited with the help of the word for 'this' ( ngaanya or ngaatja ). Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara can be summarized in a common group as Nyangatjatjara and thus distinguish themselves from Ngaatjatjarra. Pitjantjatjara uses word endings to express plural, verb tenses and moods.

Only about 20 percent of Pitjantjatjara speak English. That caused controversy in May 2007 when the Australian government launched a measure to force Aboriginal children to learn English. Between 50 and 70 percent can read and write in their own language. There is great resentment among these Aborigines at the lack of recognition of their language by the government and the Australian people.

The longest official name of a place in Australia is a word in Pitjantjatjara, Mamungkukumpurangkuntjunya Hill in South Australia, which literally means "where the devil pees".

literature

- Duguid, Charles. 1972. Doctor and the Aborigines . Rigby. ISBN 0-85179-411-4 .

- Glass, Amee and Hackett, Dorothy. 1979. Ngaanyatjarra texts. New Revised edition of Pitjantjatjara texts (1969) . Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra. ISBN 0-391-01683-0 .

- Goddard, Cliff. 1996. Pitjantjatjara / Yankunytjatjara to English Dictionary . IAD Press, Alice Springs. ISBN 0-949659-91-6 .

- Hilliard, Winifred. M. 1968. The People in Between: The Pitjantjatjara People of Ernabella . Reprint: Seal Books, 1976. ISBN 0-7270-0159-0 .

- Isaacs, Jennifer. 1992. Desert Crafts: Anangu Maruku Punu . Doubleday. ISBN 0-86824-474-0 .

- James, Diana. Painting the song: Kaltjiti artists of the Sand Dune Country . McCulloch & McCulloch. Balnarring, Australia 2009.

- Kavanagh, Maggie. 1990. Minyma Tjuta Tjunguringkula Kunpuringanyi: Women Growing Strong Together . Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara Women's Council 1980-1990. ISBN 0-646-02068-4 .

- Tame, Adrian & Robotham, FPJ 1982. MARALINGA: British A-Bomb Australian Legacy . Fontana / Collins, Melbourne. ISBN 0-00-636391-1 .

- Toyne, Phillip and Vachon, Daniel. 1984. Growing Up the Country: The Pitjantjatjara struggle for their land . Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-007641-7 .

- Wallace, Phil and Noel. 1977. Killing Me Softly : The Destruction of a Heritage . Thomas Nelson, Melbourne. ISBN 0-17-005153-6 .

- Woenne-Green, Susan; Johnston, Ross; Sultan, Ros & Wallis, Arnold. 1993. Competing Interests: Aboriginal Participation in National Parks and Conservation Reserves in Australia - A Review . Australian Conservation Foundation . Fitzroy, Victoria. ISBN 0-85802-113-7 .

Web links

people

- Yalata Land Management

- Western Desert Entry in the AusAnthrop data collection

- Pitjantjatjara People at Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements (ATNS)

language

Individual evidence

- ↑ WARU Community Directory ( Memento of the original from February 19, 2014 in the web archive archive.today ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ ABS (2006) Population Characteristics. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians ( Memento of the original from October 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. pdf, accessed November 18, 2008

- ↑ Article in the Guardian