Mother Courage and her children (film adaptation)

As early as 1947, Bertolt Brecht developed plans to film his anti-war play Mother Courage and Her Children . The 1938-39 wrote in exile in Sweden drama plays in the Thirty Years' War : The sutler Mother Courage tries to do their business with the war, she loses her three children.

Despite various failed attempts to make the play into a film with an audience appeal, Brecht wanted a film from the outset that would follow his concept of epic theater and document the performance of the Berliner Ensemble . He fought with all means against the intentions of the GDR government and DEFA , who wanted to create an opulent historical film with international stars, and in doing so also took on big politics. Even in the cinema, Brecht did not want to reach the audience through identification and great emotions, but rather through thinking from a distance. In order to achieve this distance for the viewer, he also developed special alienation effects for the film .

From the DEFA the drama was only in 1961 after Brecht's death under the direction of Manfred Wekwerth and Peter Palitzsch filmed in the style of the Berlin production (see Mother Courage and Her Children ).

The performance of the Berliner Ensemble as a model for the film

Despite the great success with the public, the Berlin production questioned the cultural and political concepts of the GDR from the start. The GDR cultural policy expected proletarian heroes, positive role models with which the public could identify. Brecht, on the other hand, showed the failure of his mother's courage. It was not the characters on the stage that showed the way, but the audience should learn from their mistakes.

The young employee of Brecht's Manfred Wekwerth , who later became the director of the film, comments on Brecht's efforts to attract the proletarian audience as follows: Even before the premiere, “he insisted on doing a screening in front of factory workers. ... He spoke to them after the performance. The workers had many questions and criticisms at the unfamiliar performance, there was also abrupt rejection and incomprehension. Brecht answered everything with great patience. ... That was the audience for which Brecht wrote or wanted to write with preference. "

On January 11, 1949, the premiere took place with great success. From the Berlin production, Brecht had the “Courage model” developed, a collection of photos by Ruth Berlau and Hainer Hill , stage directions and comments that were to serve as a model for all further performances - also at other theaters. This model also shows the line that Brecht wanted to take with regard to a film adaptation.

Film adaptations

Early plans and preliminary work

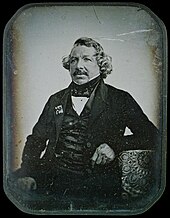

In 1947 Emil Burri got in touch with Brecht about the film adaptation of the life of Galileo . In a letter from Santa Monica dated September 1947, Brecht suggested Mother Courage as an alternative for the film without explanation. Brecht rejected a first draft of the script by Robert Adolf Stemmle in September 1949. Early on, Brecht was looking for ways to transfer his concept of epic theater to film, to “switch off the naturalistic”. One of Brecht's technical ideas was to strive for a daguerreotype-like photograph and to decorate it sparingly in the same way as his stage sets.

In early 1950, Alexander Graf Stenbock-Fermor and Joachim Barckhausen took on the task of developing a script. Various consultations took place with Brecht. Erich Engel should take over the direction . There is a typescript about the content of the planned film with handwritten notes by Brecht and others. In addition to a few small changes, the first thing that catches the eye is the new figure of the miller, who becomes Kattrin's lover and offers her an alternative way of life. The large and small deals between the armies are also clearly shown, Eilif is portrayed much more negatively than robbers. In the sketch, Kattrin takes the baby into the car and hides it there, but the mother lets him disappear a few days later. At the end of the script, indignant peasants take revenge for the murdered Kattrin. The courage still dragged on after the troops.

In September 1950, Brecht proposed Emil Burri as the new screenwriter to DEFA. There was now a dispute about the end of the film and the reinforcement of the positive perspectives. In a short synopsis with the title “How must Mother Courage be filmed?”, Brecht promised a more positive conclusion:

“The end of the play, which is to be reinforced in the film, shows how one of her children, the mute Kattrin, becomes rebellious against the war and saves the threatened city of Halle. In the film you will see how their example leads the impoverished peasants to fight the plundering Soldateska. "

From January to June 1951, to Brecht's satisfaction, Burri prepared a first version of the script that has not survived. The start of shooting failed because of Erich Engel, who was involved in the West. Burri began working on the second version of the script, supported by Brecht and the director Wolfgang Staudte . On February 18, 1952, Burri had completed a second draft of the script, but the conflicts remained. Although the courage was markedly more negative and revolutionary approaches with the figure of the miller and the rebellious peasants had been introduced, DEFA continued to criticize purely pacifist tendencies and the inadequate refutation of the religious war. Erich Engel withdrew because of the disputes.

In June 1952 another version of the script was completed, but DEFA hesitated. Brecht went more and more on a confrontational course with DEFA and complained massively to GDR cultural officials about the treatment of himself and the project, most recently in May 1954 by Culture Minister Johannes R. Becher. Finally, in November 1954, the contract was signed. Brecht received $ 10,000 and DM 20,000 for world film rights, a say in cast and content, and took on the task of writing the dialogues required. Helene Weigel was promised the role of mother.

Fundamental conflicts persisted, for example with regard to the script, whose tendency to adapt to the prevailing aesthetic ideas of the GDR could not have pleased Brecht. “What is striking are the almost propagandistic sequences such as the farmers' victory, which do not match Brecht's conception of the piece. The direct portrayal of the war, which is repeatedly expressed in images of corpses and destroyed stretches of land, can hardly be reconciled with Brecht's idea of the 'thinnest and most economical images'. "

Wolfgang Staudte's failed project

On August 18, 1955, filming began under the direction of Wolfgang Staudte . Here, too, there was conflict material in the air: Staudte's successful films, which were very emotionally oriented, did not match Brecht's purist ideas. Joachim Lang comments: “At that time Staudte was considered one of the most important directors in Germany thanks to films such as ' Die Mörder sind unter uns ', ' Rotation ' and ' Der Untertan '. With their expressive, effective and suggestive imagery, these works stand in opposition to Brecht's ideas from the start. "

DEFA “was determined to turn 'Mother Courage' into a 'big film' and provided an enormous budget for eastern state film companies too: three million marks (...), Defa hired the French for the roles of the camp lover Yvette and the kitchen cop Stars Simone Signoret (fee: 120,000 marks) and Bernard Blier (80,000 marks). "

Wolfgang Staudte remembers that as a condition for his directorial work he stipulated that Brecht was not allowed to enter the studio because he knew the difficulties of working together.

“Then I wrote a new script together with Brecht and we got along really well. (...) But then the first conflicts came. I wanted to make a real international film, in cinemascope and color, with a large cast. That didn't suit Brecht. I couldn't assert myself there. The Signoret was hired for the role of the warehouse whore, the Weigel for the mother, Geschonneck as the field preacher, Blier as the cook, etc. We made test shots with uncanny meticulousness, the equipment was developed with a lot of thought. Wonderful costumes were designed - the preparations took almost a year. "

But it came to a catastrophe, Brecht began to torpedo the work, “covered the Defa staff with an abundance of telephone advice and hand-scribbled suggestions for improvement. Helene Weigel demanded a break from filming every day that she had to appear on the theater stage in East Berlin, constantly complained about the film costumes and could not accept that Staudte gave the Yvette role played by Signoret much more space than the stage version provided. "

Brecht - so Staudte - last raged in the studio, after all, he withdrew the approval for the filming. Staudte later claims to have found out that a Brecht employee had seen the extras for a film adaptation of Zar and Zimmermann , who were watching the Courage film in the studio, and thought they were the extras of the play. Brecht then vetoed and enforced it, in that Weigel refused to sign the contract. About 30% of the film had already been finished.

The real reason for the conflict - according to the director Kurt Maetzig - was that Brecht had intended from the start to make a documentation of his production and nothing else. There were specific differences of opinion right from the start: Brecht was annoyed by the fact that a post-synchronization should take place and that no original sound could be recorded. Brecht wanted daguerreotype optics, Staudte color. According to Brecht, props should only be used when they are really needed. Some of the roles also did not correspond to Brecht's ideas. Brecht's “For Staudte, considerations were purely formal games. He saw in this a huge limitation of his artistic expression. In his opinion, such a film would not have had the mass impact that everyone was hoping for. "

Despite personal intervention by SED leader Walter Ulbricht , who, according to Spiegel, suggested that Mother Courage be changed, Brecht stuck to his point of view. He saw his theater concept in jeopardy, the implementation of which he monitored with hawk eyes at every other performance. He only issued performance permits if the theaters were based on his model performance in Berlin.

The DEFA now tried to fill Mother Courage, but could neither the Munich actress Therese Giehse , who did not want to fall out with Brecht and who advised Brecht in a letter of October 5, 1955, nor Berta Drews , who was the West Berlin Senator for Culture Professor Dr. Joachim Tiburtius was not released from her contract at the Schiller Theater. Staudte fired one of his assistants, the Brecht student Manfred Wekwerth , who had tried to represent Brecht's interests during the recordings. Due to scheduling difficulties, the project was finally discontinued.

DEFA film as documentation of the theater production

(See also: Mother Courage and Her Children )

In 1959, DEFA engaged Manfred Wekwerth again - in collaboration with another member of the Berliner Ensemble, Peter Palitzsch , he should now tackle a film adaptation of the Courage material. Wekwerth and Palitzsch described their project as a "documentary adaptation after the performance of the Berliner Ensemble".

The initial situation for Wekwerth and Palitzsch seemed favorable: Brecht had made an international breakthrough with “guest performances in Paris” and his theater was “no longer exposed to the same hostility in the GDR as in the early 1950s”. In addition, there was already a successful GDR television documentary of one Production of Brecht's “ Die Gewehre der Frau Carrar ”, directed by Brecht employee Egon Monk , which was broadcast on September 11, 1953.

In silent films and in film technology, they looked for ways of implementing Brechtian alienation effects on film and in doing so tied in with considerations on technical alienation possibilities that Brecht had already made in 1950. They used special film development techniques, such as double exposure, brown tint , coarse grain and hard contrasts, reinforced by hard lighting to emphasize the chronicle character. "Calm camera" and extreme reduction of cuts were further concepts. As an analog cinematic means for projecting subtitles onto the curtain in the theater, they occasionally reduced the cinematic widescreen format, for example in the case of the songs, through “the so-called Kasch (narrowing of the cinemascope format by sliding panels on the side)”.

They also faded in wide-format steel engravings by Jacques Callot from the time of the Thirty Years' War between scenes. They avoided close-ups of the faces. Palitzsch explained: “Close-ups of the faces induce pity. But we want people to think for themselves. ”This is how the film studio became a theater stage:

“The scenery that the stagehands erected in the south hall of the film studio town of Babelsberg resembled a stage set rather than a film set. As the script dictated, the floor was 'laid out with coarse, light plucking up to the clearly marked horizon line'; the painted circular prospectus indicated an avenue of poplar trees. A large revolving stage formed the center of the play area. "

However, the staging for the film was not simply recreated. This becomes clear, for example, in the filmic implementation of the scene around Tilly's death: While in the theater the field preacher reports on Tilly's burial, which is invisible to the audience, and in the foreground the courage socks count and subversive speeches, the film realizes the same contrast on film: " The captain's funeral is staged as a funeral procession in the rain; in the foreground stands a mercenary raising a cup in honor of the dead. ”The film shows the funeral, the stage only describes it. The good-humored Landsknecht demonstrates his indifference to the fate of the great with gestures. "The ironic mockery takes place on the stage through the word, in the film through the image."

The black and white film's camera and lighting were sober and harsh. Joachim Lang describes the camera work as cool and documentary. “The cameraman Harry Bremer , who came from the documentary film , photographed Courage in a matter-of-fact, sober manner. This creates a distance to the events and the title character, who wants to earn money from the war despite the many victims and is becoming increasingly hardened. Bremer uses uniformly strong light, so that any impression of an idyll is eliminated from the outset. The contrasts increasingly disappear. People and objects merge, they rag at the same time. "

Just like the viewer's gaze in the theater, the camera usually stays at a distance, shows what is happening from the outside and not from the perspective of one of the characters. However, this assumption of the theater perspective is not always adhered to. In the 10th scene a voice from a farmhouse sings the song about staying: “Well, those who have a roof on now / When such snow winds blow.” The camera transports the viewer inside the house and lets him with the courage that passes outside watching her daughter through an icy window.

“The lostness of mother and daughter is expressed much more strongly in the film. (...) The complacency of the song relates directly to the viewer through the change in perspective. His point of view is inside the house. This is a criticism of the retreat into private happiness. "

Brecht staged the second and third pictures in the drama as a double scene. The film shows the simultaneity of two events by dividing images. In the third scene, the parallelism is shown by panning the camera.

On the occasion of Brecht's 63rd birthday on February 10, 1961, the film was shown for the first time in 15 cinemas in the GDR, after it had been approved by a commission from the Ministry of Culture. Despite praise for the performance of Helene Weigel and the statement that the film is characterized by "a high artistic level", reservations were also expressed about formalism allegations.

Friedrich Luft , at that time one of the most important theater critics in the West, thought the experiment of transferring the alienation effect to film had failed. The viewer is not caught in the action, he is “released from the illusion again and again in three long hours in the cinema. The three hours are like six for him. ”According to Spiegel, the audience success was limited, after 7 days the film was moved from Berlin to a cinema in Friedrichsfelde . Leading actress Helene Weigel admitted: “We don't know whether the audience will like our film. It will have to reach out to him. "

Joachim Lang gives other information about the audience success in his study of the film: “In 45 screenings in the first week it was seen by over 22,000 viewers, which corresponds to an occupancy rate of 81.6% in the cinemas. Nevertheless, the film was taken out of the Berlin cinemas after a week, even though the occupancy rate there was 64.2%. ”The investigation could not clarify the reason for the cancellation.

The official GDR press reacted moderately to the experiment. The New Germany considered the film an instructive “attempt to bring the theatrical and the cinematic to an alliance.” Manfred Jelinski expressed himself very positively in the “Deutsche Filmkunst”. "Wekwerth and Palitzsch have found the only possible form for him, Bertolt Brecht, more precisely, to transport this piece onto the canvas."

The film had an interesting aftermath in 1977: According to DEFA documents, Brechtsohn is said to have offered Stefan $ 10,000 for the destruction of all but one of the copies of the film on the occasion of a remake in the USA, which was rejected by GDR government agencies. The rights to the film remained with DEFA.

literature

Text editions drama

- Mother Courage and her children . Stage version by the Berliner Ensemble, Henschel, Berlin 1968.

- Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. A chronicle from the Thirty Years War , 66th edition, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2010 (first edition 1963), ISBN 978-3-518-10049-3 (edition suhrkamp 49).

- Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and Her Children , in: Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 6): Pieces 6 Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 978-3-518-40066-1 , pp. 7–86.

- Bertolt Brecht; Jan Esper Olsson (Ed.): Mother Courage and Her Children - Historical-Critical Edition , Liber Läromedel, Lund 1981, ISBN 91-40-04767-9 .

filming

- Screenplay for the film "Mother Courage"; in: works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (volume 20): Prosa 5, appendix scripts, Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-40020-7 , pp. 215–384

- Bertolt Brecht: The Courage Film (Short Summary); in: works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 20): Prosa 5, Notes, Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-40020-7 , pp. 582-587

- Bertolt Brecht: How does “Mother Courage” have to be filmed? in: works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 20): Prosa 5, Notes, Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-40020-7 , pp. 587-590

- Bertolt Brecht: Innovations in the COuragefilm; in: works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 20): Prosa 5, Notes, Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-40020-7 , pp. 590-591

- Mother Courage and her children , DEFA film 1959/60, based on a production by Bert Brecht and Erich Engel in the Berliner Ensemble , with Helene Weigel , Angelika Hurwicz , Ekkehard Schall , Heinz Schubert , Ernst Busch and other ensemble members, film director: Peter Palitzsch and Manfred Wekwerth , music by Paul Dessau

Secondary literature

- Bertolt Brecht: Texts on Pieces, Writings 4, in: Berliner and Frankfurter Edition Vol. 24, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 1991

- Bertolt Brecht: Couragemodell 1949. in: Schriften 5, Berliner and Frankfurter Edition, Vol. 25, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 1994, pp. 169–398

- Bertolt Brecht: Letters 2, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, Volume 29

- Kenneth R. Fowler: The Mother of all Wars: A Critical Interpretation of Bertolt Brecht's Mother Courage and Her Children. Department of German Studies, McGill University Montreal, August, 1996, A thesis subntitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy [1]

- Werner Hecht: Materials on Brecht's "Mother Courage and Her Children", Frankfurt am Main 1964

- Manfred Jäger: On the reception of the playwright Brecht in the GDR. Text + criticism. Special volume Bertolt Brecht 1. (1971), pp. 107–118

- Jan Knopf: Brecht-Handbuch, Theater, Stuttgart (Metzler) 1986, unabridged special edition, ISBN 3-476-00587-9 , comments on Mother Courage pp. 181–195

- Joachim Lang : Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's Stage Plays in the Audiovisual Media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3496-1 , ISBN 978-3-8260-3496-1

- Karl-Heinz Ludwig: Bertolt Brecht: Activity and reception from returning from exile to the founding of the GDR, Kroberg im Taunus 1976

- Klaus-Detlef Müller: Brecht's "Mother Courage and Her Children" . Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt, 1982. ISBN 3-518-38516-X (extensive anthology with articles and other materials)

Web links

- Manfred Wekwerth: What does reality actually mean on stage? or The real chances of the theater . Marxist sheets 4/2009

- Manfred Wekwerth: Political Theater and Philosophy of Practice or How Brecht Made Theater November 23, 2005

Individual evidence

- ↑ Manfred Wekwerth: Political Theater and Philosophy of Practice or How Brecht Theater Made November 23, 2005 ( Memento of the original from February 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Notes on the Courage model, in: Bertolt Brecht, Berliner and Frankfurter Edition, Schriften 5, Vol. 25, pp. 516f.

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Briefe 2, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, Volume 29, Letter 1252, p. 422f.

- ^ Bertolt Brecht: Journale 2, Berlin and Frankfurter Edition, Volume 27, p. 307, October 14, 1949

- ^ Bertolt Brecht: Journale 2, Berlin and Frankfurter Edition, Volume 27, p. 307, October 14, 1949

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, volume 20, p. 581

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, volume 20, p. 582

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, Volume 20, pp. 582-587

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, Volume 20, pp. 587f.

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, volume 20, p. 588

- ↑ cf. Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, Volume 20, pp. 587–591

- ↑ cf. Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, Volume 20, pp. 591–593

- ↑ a b Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's Stage Plays in the Audiovisual Media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 232

- ↑ a b c d The mirror, BRECHT. Colored brown. January 20, 1960, p. 49; in other roles: Mother Courage: Helene Weigel; Kattrin: Siegrid Roth ; Eilif: Ekkehard Schall ; Swiss cheese : Joachim Teege ; Field preacher: Erwin Geschonneck; Müller: Hans-Peter Minetti ; Source: Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, volume 20, p. 593

- ^ Ingrid Poss, Peter Warnecke: Trace of Films. Contemporary witnesses about DEFA, Ch. Links Verlag, 2nd edition (November 27, 2006), ISBN 3-86153-401-0 , p. 100

- ↑ cf. Ingrid Poss, Peter Warnecke: Trace of Films. Contemporary witnesses about DEFA, Ch. Links Verlag, 2nd edition (November 27, 2006), ISBN 3-86153-401-0 , p. 101

- ↑ cf. Ingrid Poss, Peter Warnecke: Trace of Films. Contemporary witnesses about DEFA, Ch. Links Verlag, 2nd edition (November 27, 2006), ISBN 3-86153-401-0 , p. 102f.

- ↑ cf. Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's stage plays in audiovisual media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 232ff.

- ↑ cf. Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's stage plays in the audiovisual media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 234

- ↑ cf. The mirror, BRECHT. Colored brown. January 20, 1960, p. 49

- ↑ Der Spiegel, Mutter Blamage, November 23, 1955, p. 55

- ↑ a b c cf. The mirror, BRECHT. Colored brown. January 20, 1960, p. 50

- ↑ The mirror, BRECHT. Colored brown. January 20, 1960, p. 50; see also the DEFA website

- ↑ Manfred Wekwerth; Peter Palitzsch: About the film adaptation of Mother Courage and her children. Berlin 1961, quoted from: Klaus-Detlef Müller: Brecht's "Mother Courage and Her Children" . Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt, p. 257

- ↑ a b cf. Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's Stage Plays in Audiovisual Media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 235

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Prosa 5, Berlin and Frankfurt edition, volume 20, p. 581

- ↑ a b c MOTHER COURAGE. Seven Years War. MOVIE. Der Spiegel of March 15, 1961, p. 87

- ↑ a b Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's stage plays in the audiovisual media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 241

- ↑ Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's Stage Plays in the Audiovisual Media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 247

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and Her Children , in: Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 6): Pieces 6 Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 78

- ↑ Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Bertolt Brecht's Stage Plays in the Audiovisual Media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 253

- ↑ a b Materials on the Mutter Courage film, Federal Archives; quoted from: Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Stage plays by Bertolt Brecht in the audiovisual media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 264

- ↑ a b c MOTHER COURAGE. Seven Years War. MOVIE. Der Spiegel of March 15, 1961, p. 88

- ↑ Manfred Jelinski in: Deutsche Filmkunst 1961, p. 112; quoted from: Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Stage plays by Bertolt Brecht in the audiovisual media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 265

- ↑ cf. Materials for the film version of Mother Courage, Federal Archives; quoted from: Joachim Lang: Epic Theater as Film: Stage plays by Bertolt Brecht in the audiovisual media, Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 264