Mother Courage and her children (setting)

The setting of the drama Mother Courage and Her Children includes the creation of the incidental music for this play, the resulting scores and their interpretation and changes in performance practice. The author Bertolt Brecht had planned a musical arrangement from the outset for the drama , which was written in exile in Sweden in 1939 . The original version already contained a number of songs , most of which had melodies from various composers. Subsequently, Brecht looked for composers who were to develop new music that was coherent for the entire piece on this basis; But he insisted on a certain melody, especially for the thematic song of Mother Courage . The drama was set to music three times, initially by the Finnish composer Simon Parmet . This composition is considered lost. The music for the premiere of Mother Courage in Zurich on April 19, 1941 was composed by Paul Burkhard , who also conducted it himself. The premiere at the Deutsches Theater Berlin on January 11, 1949 was musically designed by Paul Dessau in collaboration with Bertolt Brecht. As the author of the piece, Brecht declared Dessau's music to be binding; it was therefore used in all subsequent performances.

The mother Courage is exemplary of Brecht's concept of epic theater . Music and songs play a special role. The actors step out of their role as singers commenting, addressing the audience, creating distance from the action on the stage. However, unlike in earlier pieces, the songs are more closely integrated into what is happening on stage.

History of origin

When Brecht wrote Mother Courage in 1938/1939 in exile in Denmark and Sweden, he could not rely on his long-term production partner Hanns Eisler , who was in the USA, for the music . Nevertheless, he wanted to integrate musical elements into the drama. Time was pressing because Brecht was planning a performance of the piece in Scandinavia soon. Therefore, the conception of the songs was largely based on the recycling of earlier compositions.

The original version of the piece contained almost exclusively songs that either already existed or for which at least a melody was available. Brecht integrated the ballad of the woman and the soldier , which was already available in two musical versions, by Franz Servatius Bruinier in collaboration with Brecht himself (from the house postil ) and by Hanns Eisler. The Salomon song , set to music by Kurt Weill , had already been part of the Threepenny Opera and was only textually modified for Mother Courage . The ballad vom Wasserrad , set to music by Eisler, was originally intended for Courage, but was eliminated in the course of the work. The song from Surabaya-Johnny , composed by Kurt Weill, was apparently initially to be incorporated in its original form, but Brecht then fundamentally changed the text and title in the manner of a counterfactor . This first became the song of the whistling and drum henny , later the song of fraternizing . The song of Mother Courage was designed from the outset as a counterfactor, based on the melody of the ballad of the pirates from the house postil . There were also melody templates for other pieces: The melody of Prinz Eugen, the noble knight was to be used for the initially planned song “When we were lying before Milano”, the song from the home was based on a hymn for the lullaby (“Eia popeia “) Helene Weigel is said to have given a folk tune. Only for the song of the great surrender could no template be found.

The plans for a world premiere in Scandinavia came to nothing because of the war situation and the resulting further steps by Brecht to emigrate; but the Zürcher Schauspielhaus expressed interest in a production. In this context, Brecht abandoned the idea of a “ pasticcio ” of various compositions. He initially considered a setting by Hilding Rosenberg or Hanns Eisler, to whom he sent the typescript of the piece to America, but finally asked the Finnish composer Simon Parmet , whom he met in exile in Helsinki, for a complete setting of the songs.

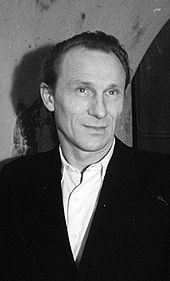

Simon Parmet

Little is known about Parmet's setting. The sparse information comes from scattered remarks in Brecht's work journal and from an article by the composer in the Schweizerische Musikzeitung from 1957, which first made their existence known. The score is considered lost.

Working with Parmet, it quickly became apparent that Brecht had not only pragmatic but also artistic reasons for his decision to use existing pieces of music. He imagined the musical numbers as “mechanical sprinkling”, “something in them of the sudden clang of those retail equipment into which one throws a penny”. He asked Parmet to orientate himself stylistically on the songs from the Threepenny Opera . He sang, whistled and drummed the melody of L'Étendard de la Pitié to Parmet several times and demanded the use of this melody for the performance song of Mother Courage. Parmet was not very enthusiastic about the imposition of a kind of style copy of Weill's music and wanted to stop after composing three songs, but was then persuaded to compose all the pieces requested.

On February 1, 1941, Brecht sent a finished piano reduction to the Kurt Reiss theater publisher , where the text for the premiere was already located. In the event of final acceptance, he held out the prospect of an instrumentation for a seven- to eight-member orchestra, but allowed the theaters to use other music, which, however, had to be approved by him.

What exactly this vocal score contained is not clear, since both Parmet's autograph and Kurt Reiss's archive have been lost. In any case, the director of the premiere, Leopold Lindtberg , received musical material, but what this consisted of can no longer be clarified. Lindtberg only remembers having received "a few notes", including the song of Mother Courage and the lullaby ; his wife Valeska Lindtberg, then musical assistant at the Zürcher Schauspielhaus, says that Brecht sent what he called "old Landsknechtslieder" and only the singing part of them. In any case, Parmet's setting was never performed; his work is presumably preserved mainly in the lullaby of the world premiere.

Paul Burkhard

Whatever the material, in whatever form and volume, arrived in Zurich - the stage music for the premiere was in any case created by the resident composer of the Zurich Schauspielhaus, Paul Burkhard, who is known for his operettas . He not only wrote the instrumentation and rehearsed it, but also composed most of the songs from scratch.

Only three of the ten numbers did not come entirely from Burkhard, as can be seen from a list by the composer for the theater publisher Kurt Reiss: The ballad of the woman and the soldier was taken over in the version set by Hanns Eisler, because, as Valeska Lindtberg believes, couldn't write more beautifully; Burkhard copied Eisler's piano version and wrote out the instrument parts. He took over the melody of the “opening stanza” of the song by Mother Courage in the form he had received from Brecht, but set the refrain to music anew. And finally he took over the lullaby from the "friend Brecht's, who provided the songs, some of which we then left out", probably from Simon Parmet. This is also supported by the fact that Parmet claims to have recognized the song at a performance in Helsinki. On the other hand, the Zurich team apparently did not know Weill's setting of the Salomon song , at least not used it. The song of the pipe and drum henny was left out without further ado. Instead, Burkhard added a wordless “Pfeiffer and Drummers March”.

Burkhard seems to have worked very quickly. Apparently he only needed one day to compose the songs (March 27, 1941), and on the following day he began to rehearse with Therese Giehse (the mother Courage of the premiere). The final score was already available on April 15, and it included six instruments: piano, harmonium, accordion, flute, trumpet, and drums. The premiere took place on April 19th.

Burkhard's music received excellent reviews and was used for all performances until 1946, sometimes even considerably later; However, Brecht does not seem to have known her at least until 1948.

Paul Dessau

In 1943 Brecht met Paul Dessau while in exile in America. Brecht performed songs from Mother Courage in Dessau in 1946, and the latter set them to music “in close collaboration with Brecht”, a form of cooperation that Brecht knew and valued from his earlier composers.

The cooperation was not without friction. Dessau was irritated by Brecht's “polite” hint that he “wanted to have used” the Dessau melody by L'Étendard de la Pitié for the song of Mother Courage - “this kind of plagiarism” was completely alien to him at the time. On the other hand, Dessau also had reservations about composing the song of the woman and the soldier anew, as he was already familiar with Eisler's setting, which he valued. Brecht went into this insofar as he inserted a scene instruction that Eilif should perform a saber dance while singing the song - so Dessau received a new starting point for his own setting. In the course of cooperation, the idea came up to prepare the piano: By drawing pins on the hammers there should be a guitar or harpsichord-like get sound. This so-called bug piano or guitar piano was then preserved in all later versions.

In August 1946 Dessau completed a first version, the so-called “American version”, which comprised a total of twelve musical numbers and was dedicated to Helene Weigel . It did not yet contain the “Little Soldier's Song”, but instead an instrumental prelude and two marches. Brecht, who was very satisfied, lost no time and immediately let Kurt Reiss know that Dessau's music was to be used in all performances.

Paul Burkhard, who was informed of this decision by the theater publisher, reacted with dismay and expressed his wish in a letter that Brecht should get to know his music first. This did not happen until February 25, 1948, when Brecht was in Zurich; Burkhard invited him to a meeting at his home, in which the Lindtbergs, Therese Giehse (the mother Courage of the premiere), Hans Albers and Rolf Liebermann also took part. According to Leopold Lindtberg's report, however, the evening turned out to be rather unfortunate: Burkhard is said to have played his popular operetta melodies on the piano (including O my Papa ), which Brecht recorded with the greatest reserve; only then did he get to his Courage songs. Lindtberg remembers that it "really hurt him that Brecht got such a wrong impression of Burkhard's music". In any case, it remained with Brecht's copyright-binding commitment to Dessau's music. However, according to a letter from Burkhard, Burkhard's incidental music was still used in the Vienna premiere of Courage at the New Theater in Scala in 1948 - Therese Giehse had not been able to cope with Dessau's multiple time changes in the song of Mother Courage .

Dessau began in 1948 with a revision of the "American version". He responded to Brecht's text changes and made various revisions to his composition, for example by adding a syncope to the word God in the song of the great surrender to express the colon in the verse Man thinks: God directs musically. Most of the changes were directly related to Dessau's participation in the world premiere (he did the rehearsal himself). As can be seen from a letter from Brecht to Dessau, the issue was, among other things, the "rapid adjustment to the available resources"; At the same time, however, Brecht attested to Dessau that it had “even created new beauties”. Dessau also completed the score by post-composing the Little Soldier's Song and some marches , trumpet signals and inter-act music. Two piccolo flutes and flutes , two trumpets (always played con sordino ), drums , guitar , accordion , harmonium and the prepared guitar piano were provided for the orchestra ; a jew's harp was used on the stage .

Rework

That was by no means the end of the work on the setting. It continued to flow, depending on the circumstances of the respective rehearsal and performance. So it was added to the Berlin premiere in 1949 that in the third picture the cook sings ironically the well-known Protestant confession song A strong castle is our God . On the other hand, Brecht deleted the Horenlied , which he valued because it could not be played properly with the human and material resources of the German theater , and declared the song to be a test of the qualities of the theater: it could only be sung where the conditions were good enough . It was not until 1951, when the Berliner Ensemble performed for the first time, that this song came on stage for the first time.

Dessau also composed another song for this performance, the song of the Pfeifenpieter , the text of which is not by Brecht but by Ernst Busch , who played the cook and also sang the song. The lyrics and the ways were based on an old Dutch song. Furthermore, at the suggestion of Helene Weigel, experiments were carried out to move the first two verses of the Courage song into the prologue . A final score was not printed until 1958 after Brecht's death. But even this did not lead to a canonical form of setting. So recalls Thomas Phleps because even in the 1980s as a stage musician at Kassler Theater regularly Eisler'sche version of the song from the woman and the soldier to have played.

Overview of the songs

| image | Song title, beginning | template | variants | New compositions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Mother Courage's song "Your lieutenants let the drum rest" |

Ballad from the pirates : Postille from the French chanson L'Étendard de la Pitié , text: Brecht |

New wording, repeated text changes after the premiere | Zurich: Burkhard Berlin: Dessau each using the template |

| 2 |

Ballad of the woman and the soldier "The rifle shoots and the spear knife spears" |

From: Hauspostille , later integrated into incidental music for Calcutta, May 4th ( Lion Feuchtwanger ) Music: Eisler, text: Brecht |

only minor text changes | Zurich: Eisler's version Berlin: Dessau |

| 3 |

Song of the Fraternization "I was only seventeen years old" |

Surabaya-Johnny , from: Happy End , music: Weill | initially = template then slight text adaptation and new title: Song of the Pipe and Drum Henny, finally new text, initially under the title Song of the Soldier Whore |

Zurich: deleted Berlin: Dessau |

| 3 |

Horenlied "In the first hour of the day" |

Christ who makes us happy (hymn by Michael Weisse , around 1520) | Selection and minor editing of stanzas 2 to 6 by Brecht only added in 1946 |

Zurich: not yet available. Berlin: Dessau |

| 4th |

Song of the great surrender "Once upon a time, in my early years" |

? | first under the title Song of Waiting | Zurich: Burkhard Berlin: Dessau |

| 5 |

Little soldier's song "A schnapps, landlord, quick, be smart" |

? | since the first typescript | Zurich: Burkhard Berlin: Dessau |

| When we moved in front of Milano | Prince Eugene, the noble knight | considered in the planning phase as an alternative to the Little Soldier's Song | - | |

| 7th |

Song of the mother Courage "And he goes beyond your strength" |

s. Image 1 | Half strophe added for the Berlin premiere | s. Image 1 |

| Ballad from the water wheel | From: The Round Heads and the Pointed Heads Music: Eisler, Text: Brecht |

still in the first typescript, already eliminated in the Zurich version | - | |

| 8th |

Song of the mother Courage "From Ulm to Metz" |

s. Image 1 | s. Image 1 | s. Image 1 |

| 9 |

Solomon song "You saw wise Solomon" |

from: Threepenny Opera Music: Weill, Text: Brecht |

Text adjustments, new stanzas | Zurich: Burkhard Berlin: Dessau |

| 10 |

Song of the abode "A rose has seduced us" |

“Folksong” (Brecht), presumably: A rose has sprung from it | new text | Zurich: Burkhard Berlin: Dessau |

| 12 |

Lullaby "Eia popeia" |

Based on the lullaby from Des Knaben Wunderhorn ("Eio popeio, was rattelt im Stroh"), melody based on a memory by Helene Weigel | Adoption of the opening verses and rewording of further stanzas | Zurich: NN (Parmet?) Berlin: Dessau both using the melody |

| 12 |

Song of the mother Courage "With his luck, his vehicles" |

s. Image 1 | s. Image 1 | s. Image 1 |

Brecht's conception of music and songs

Song form: music as part of the work

When conceiving and writing his texts, Brecht often had the lecture in mind. Above all, poems and songs were often conceived from a musical structure. This also applies to the mother Courage . The importance of the songs and their performance in Brecht's eyes can already be seen in the production history. An overview of the scenes from an early stage of the development history hardly contains any details of the plot, but does contain information about the songs that correspond to the individual scenes. In the first scene there are individual snippets of text from the later song of the mother Courage and the word "Seeräuber" - a reference to Brecht's own ballad about the pirates , written in the early 1920s , which had long been set to music in the notes attached to the house postil with the note: “The melody is that of L'Etendard de la Pitié .” The song by Mother Courage was therefore intended from the start as a counterfactor to this melody. Accordingly, it uses the meter of the pirate ballad , an iambic four-lifter with a caesura after the second foot of the verse . Brecht often used such subdivided verse forms that he had already found (for example in the memory of Marie A. ); they gave him the opportunity to use the caesura as a turning point or to play it over freely.

Other songs from the mother Courage are even more based on found or self-written models, regularly already available in set music, right up to the simple reuse without significant change. All songs are in forms that are reminiscent of the folk song verse : There is usually a more or less strictly treated meter, end rhyme and often also a verse - refrain structure. The ballad of the woman and the soldier differs most from the emphasized simplicity of the pieces, which makes a clearly more artificial impression with its changing rhythms and internal rhymes .

Over the entire history of the creation of the piece, Brecht gave his composers considerable freedom, but insisted on certain melodic, rhythmic or general stylistic elements. This is especially true of the song by Mother Courage , the melody of which he strongly recommended to all composers involved. It was all about the character of recognizability. However, he encouraged Paul Dessau to completely re-set songs already composed by Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler - although the Salomon song and the ballad of the woman and the soldier had already achieved considerable publicity. Here, of course, the recognizability was given by the text.

Music in Epic Theater: The Separation of the Elements

True to Brecht's conception of epic theater , the songs have the task of enabling the singer to step out of the role of the actor: In the song, the actor addresses the audience and, if necessary, secondarily to the other characters in the play. The songs convey reflections, during which the action stands still.

In doing so, Brecht was primarily concerned with separating the elements: the music is intended to have an independent role, not as a duplication and support of the drama, but as a musical commentary. Brecht made this clear at an early stage in a suggestion to Simon Parmet regarding the Courage music, which he also noted in his work journal:

- "May I incite you?" I say. “Your chance as a musician lies in the orchestra, as small as it may be. You had to hand over the melody to the non-musician, the actor […] It's true, the non-musician upstairs must also have the support points, otherwise he'll fall over, but every instrument that you get free from this service is won for you, for the music, sir! Remember, the instruments don't speak by 'I', but by 'he' or 'she'. What forces you to share the feelings of 'me' on stage? You are entitled to take your own position on the subject of the song. Even the assistance you lend may make use of other arguments. Emancipate your orchestra! "

Brecht emphasized this independent function of the music (as well as the stage design ) in his courage model, now based on the final music of Dessau, with a special emphasis on the active role of the viewer and listener: “Paul Dessau's music for courage is not mainly catchy; As with the stage construction, the audience was left with something to do: the ear had to unite the voices and the manner. Art is not a land of milk and honey. "

The songs, which interrupt the action again and again in order to interpret and interpret it, contribute to the "tearing of the illusion" - not the courage sings, but the actress who sings the courage. A song is thus an alienation effect in the sense of Brecht. In his Berlin production from 1949, Brecht clearly set the music apart from the rest of the stage. A "musical emblem [...] made of trumpet, drum, flag and lampballs that lit up" was let down from above in the songs, and more and more "torn and destroyed" during the course of the performance. This did not apply to the incidence music, such as the marches in the background or the Little Soldier's Song , but only to the reflective songs: the song of Mother Courage , the ballad of the woman and the soldier , the song of fraternization , the song of the great Surrender , the Solomon Song and the Horenlied . The small music ensemble was in a box, clearly separated from the stage. These tricks served to convey the "correct impression" that the songs were "interludes". The “erratic, 'inorganic', assembled” should be emphasized in this way.

Brecht commented poetically on the singers' stepping out of their role as characters in the piece in the collection "Poems from the brass purchase" in 1951:

- “Separate the chants from the rest!

- (…) The actors

- Turn into singers. In a different posture

- Reach out to the audience, still

- The characters of the play, but now also open

- The playwright's confidante.

- (...)

- And incomprehensible

- The Sutler's Song of the Great Surrender, without

- That the playwright's wrath

- Is beaten to the wrath of the sutler. "

Integration of the songs into the plot

In addition to the continuity of the basic epic functions of the songs, there is a change in Brecht's work: unlike in earlier pieces, the songs are more closely integrated into the scene. Joachim Müller shows this change using the example of the development from the Threepenny Opera to Mother Courage: “The director's comment on the Threepenny Opera demands that the singers step in front of the curtain, illuminated by golden light, and the barrel organ is illuminated. Boards with the title of the song come from above. (...) The songs should be musical addresses to the audience and thus emphasize the general gesture of showing. ”Using the Salomon song as an example, Müller registers a“ functional change ”in Courage and differentiates between the“ ramp song ”of the Threepenny Opera and the“ scenic Song (...), which ritards the stage plot, but does not break it. ”In Courage, the songs no longer stand“ next to the plot ”, are“ not an arbitrary addition ”, but have“ a function similar to that of the choir in Greek tragedy ".

Jendreiek works out the function of interweaving scenic plot and songs.

“The songs are intertwined with the plot, develop out of it and influence the course of the plot so that they can present opinions that run counter to the plot of the piece and challenge the viewer's critical and corrective intervention. (...) By observing and analyzing the relationships between song, dramatic person and process, the cognitive value of song, person and process is determined: one can be the corrective of the other; one can alienate or substantiate each other in a contrasting way. "

Walter Hinck considers the addressees of the songs on stage, with the exception of the “Song of the Great Surrender”, to be “fictitious”. Only there does the song change the plot, the other songs "do not affect the plot itself", they "reach into the exemplary". Hinck concludes from these observations that even in the courage “none other than the spectator (...) is the addressee of the instruction or warning”. Despite the scenic anchoring of the songs, the singers were given a “dual value”: “On the one hand, he remains a figure in the aesthetic-scenic space, on the other hand he becomes a partner of the audience”. According to Hinck, the warnings and instructions of the songs cannot be trusted. With the song of the great surrender , the courage suggests to an indignant young soldier that one has to cuddle before the mighty. Just like the “warning about love in general”, the teachings of the songs are often dubious and should “stimulate the already troubled viewer to discover the cause of given contradictions not in this or that individual, but in society itself.” Essential function of the songs is to lead the audience to a socially critical interpretation of the play by "interrupting the plot" contradictions to what is happening on the stage. In addition, the songs created visible role distance for the actors through the dual function of the actor and the singer.

Structuring through the songs

Since Brecht wants to do without the tension curve of the classic drama and the individual scenes do not follow a strict structure, Brecht uses other means to structure the drama. The repetition of the song of courage from the beginning at the end of the piece forms a kind of framework, which in the Berlin production supported the repetition of the open horizon of the set. The two pictures show a clear contrast. If the first picture shows the family united on the intact wagon, the impoverished courage in the end pulls the empty wagon alone to war.

In addition, after Brecht had said goodbye to the initial idea of a pasticcio by different composers, he expected something like a uniform basic gesture from the music. If, compared to Parmet, he had considered the style of the Threepenny Opera to be appropriate, he was looking for another connecting element in Dessau's setting. It was rather a reserved, "thin", dry tone that he expected from Dessau. Text interpretation and expressiveness faded into the background. Brecht wrote to his longtime friend and colleague, the set designer Caspar Neher : "The Dessauche music for Mother Courage is really artistic, such a piece has to be performed in the noblest Asian form, thin and as if engraved on gold plates."

To Burkhard's music

Burkhard's composition was received positively by the critics. The contemporary critic Bernhard Diebold recognized the concept of the Threepenny Opera in Zurich's Courage in 1941 . He said that Burkhard had grasped the author's manner “with admirable empathy”; one could imagine that "one or the other of these songs, mixed with joy and complaints, would soon be sung". Günther Schoop, as chronicler of the Zürcher Schauspielhaus, emphasized the music that it had the "mixture of petty-singing manner and farmhand-like war song" excellently. The Basler National-Zeitung confirmed it was "a great success in terms of success". Director Leopold Lindtberg also used Burkhard's music in the 1943 production in Basel and in November 1945 when it was revived in Zurich and in numerous international guest performances by the Zurich ensemble over the next few years.

To Dessau's music

In contrast to other compositions for Brecht's pieces (such as The Caucasian Chalk Circle ), Dessau largely dispensed with exotic elements in his incidental music for Mother Courage. The otherwise recurring influences of twelve-tone music are also missing here , the music is consistently tonal. Noticeable features of the instrumentation are the use of "folk music" instruments (jew's harp, accordion) and the dry, metallic sound of the prepared piano.

Rather, Dessau tried to find a folk song tone as the characteristic of which he saw the variation and variability of given, lived patterns. The sound should give the impression "as if you were hearing well-known tunes in a new form ...".

However, Dessau alienated these familiar patterns in a specific way. This is especially true for metrics / rhythms and harmonics. The actually continuous meter types are interrupted by recurring meter changes. Often the declamation becomes downright senseless, for example by shifting the rhythmic accents. In this way, the music gains a certain independence from the text, it draws attention to the way of singing and declamation. Dessau had a pronounced aversion to march-like accentuation of the 'heavy' parts of the beat, which is clearly expressed in the shifting of the rhythmic accents.

Dessau's harmony is tonally bound in Mother Courage, but this tonal foundation is continually “damaged” (Hennenberg). Two conspicuous, frequently repeated patterns are, according to Fritz Hennenberg, “multiple thirds” (further thirds are added to the triad, so that there are dissonances: seventh, ninth, and lower decimals) and “chord perverts”, i.e. the sharpening of chords by additional dissonant disruptive tones. Dessau particularly likes to place such disturbing tones in the bass foundation of the chords, where they show very strong alienating effects.

Occasionally there are also conspicuous melisms , especially in the song of the fraternization , which probably go back to the tradition of Jewish sacred music, which Dessau knew well.

The individual songs in the analysis

Mother's song Courage

The song of the mother Courage serves as a framework for the entire piece and characterizes the protagonist and her development. It has a stanza - refrain structure, the refrain is never changed.

The first two stanzas of the song answer the sergeant's question: “Who are you?” Mother Courage first answers “business people” and then begins to sing. She addresses the officers directly and offers them their goods.

In the original of the song, Brecht's ballad from the pirates from the 1920s, the melody always begins with an upbeat , initially with the signal-like falling minor triad in eighth notes. While the stanzas are obviously based on D minor as the key, the refrain changes to the parallel major key of F major. This change also corresponds to a change of mood and tempo for the pirates : from the quick stanza with the dangers of pirate life to a much broader, emphatic hymn to heaven, wind and sea ("O heaven, radiant azure"). It ends in a four-fold repetition of the note, which gets stuck 'above' on the D and is only brought back to the root note in the following verse. Brecht's childhood friend Hanns Otto Münsterer commented that the chorus sang the “Song of Songs for the instinctual, unrestrained life of the anti-social”.

This dichotomy is introduced into the song of Mother Courage by adopting the rhythm and melody of the pirate ballad . Here, too, the stanzas provide the gloomy backdrop and partly also the progression of the plot, the refrain celebrates anarchic life again, unconcerned about the threat of death, as was already the case with the pirates . The style level is of course much lower: Here it is the unbearable life that, in the spring, if it has “not yet died”, “picks up” again.

The use of the Hauspostille material reflects Brecht's re-evaluation and re-appropriation of his hymns from the early 1920s. In 1940 he noted in his work journal on the Hauspostille poems: “Here literature reaches that degree of dehumanism that Marx sees in the proletariat, and at the same time the hopelessness that inspires it. Most of the poems are about doom, and the poetry follows declining society to the ground. the beauty is established on wrecks, the last fragments become delicate. the sublime wallows in the dust, the senselessness is welcomed as a liberator. the poet no longer even shows solidarity with himself. ”Brecht does not abandon his anti-social figures, but he changes their assessment and transfers them to a new context. Matthias Tischer comments on what this transmission could have made for the audience: “The verses of the song, reinforced by the memorability of the melody, must reflect many that had just emerged from bunkers and cellars and, bit by bit, the extent of the devastation of war and Fascism were brought to mind, have become sayings and leitmotifs in times of total loss of meaning. "

Dessau has adopted the melody practically unchanged, especially in the pitch sequence, but has set new accents through metrics, rhythm, harmony and instrumentation. Instead of the up-bar eighth note, his composition begins with full-bar quarters, underlaid with continuous staccato quarters from the accompanying guitar piano with its metallic timbre. The "graceful folds" of the template are eliminated, it gets a certain "clunkiness", a pounding, march-like appearance. Of course, this march has something dubious, “clumsy rumbling” about it due to the recurring, irregular insertions of two-quarter bars and the noticeable shortening and widening of the metric cells. It is not easy to march after this march. In the chorus, a composed slowing down of the melody by means of hemioli then thunders , i. H. the continued three-quarter time of the accompaniment is actually opposed to a three-half time in the melody. In the finale, the tempo is broadened again until whole notes form the beat; it gives the impression of stretching, in line with the text (“the war, it lasts a hundred years”).

In addition, there is an idiosyncratic rhythm: the long note values in the stanzas are on unstressed final syllables (rest, better), the result is a declamation like in bänkelsang with "wrong", senseless emphasis on the dispatch, as Brecht does with his own Also used song recitals in the 1920s.

The harmony is peculiarly obscure, as Fritz Hennenberg noted. The minor triad of the first melody phrase in the bass foundation is by no means subject to the actually required tonic in E minor, but rather a subdominant chord in A minor with the root note A, which rubs against the melody tones. This chord is repeated incessantly for 13 bars, while different harmonic functions alternate in the treble of the accompaniment (tonic, subdominant parallel, dominant ). This simultaneous harmonic function creates the impression of a “wrong” accompaniment. The harmonic functions actually required of it are withheld from the melody. The resulting “multiple thirds” are a characteristic of Dessau's song compositions. This means, too, contributes to the impression of the infinity of the march; there is no longer a regular course of tension and relaxation.

Dessau also built trumpet signals into the movement, which stand out because of their "penetratingly constant". In the last chorus there are two piccolo flutes that play falling small seconds - “ chains of sighs ”, a motif from the baroque tonal speech that expresses emblematic pain (for example in Johann Sebastian Bach ). Of course, they are stripped of their baroque beauty by being led at a seventh interval, which results in violent friction (Tischer speaks of the “screeching of the piccolo flutes”). The instrumentation has a very pictorial character: the never-ending march accompanied in pounding quarters, albeit stumbling, the trumpet signals as commands, the flutes as Landsknecht instruments.

Matthias Tischer interprets these characteristics as “symbols and emblems of the simultaneous questionability and immutability of the war”, and Gerd Rienäcker specifies that one hears “the infinite marching step, in which the gruesome words of the war, which still lasts for the 'hundred years' to find their symbolic confirmation ”.

The song of the woman and the soldier

The song was taken over by Brecht almost unchanged from his much earlier collection of poems, Hauspostille . The early version, written around 1921/22, is based on a short song by Rudyard Kipling from the end of his short story Love-O'Women (1888):

- "Oh, do not despise the advice of the wise,

- Learn wisdom from those that are older,

- And don't try for things that are out of your reach -

- An 'that's what the Girl told the Soldier

- Soldier! Soldier!

- Oh, that's what the Girl told the Soldier! "

“The Ballad of the Soldier”, as the song was called in the house postil, was initially set to music in 1925 by Franz S. Bruinier . It became known in the version by Hanns Eisler from 1928, originally composed for a drama project by Lion Feuchtwanger and Bertolt Brecht. Brecht could count on a certain recognition value for the song. The Eisler setting had been available as a record since 1930, and the song is still one of Brecht's most-played titles to this day. The Bruinier core melody, probably at least co-developed by Brecht, was retained by Eisler.

Bruinier's version clearly emphasized the gender contradiction: “While the woman's warnings are to be spoken in the stanzas, the soldier's careless answers are sung in the refrains .” When transferring the ballad from the postille to Mother Courage , Brecht changed the last lines slightly, but meaning-changing. Does it still say in the house postille :

- “Oh, bitterly repented who eschew advice from a woman !

- Said the woman to the soldier. "

Brecht wrote gender-neutral for the Courage:

- “Oh, bitterly repented who eschew the advice of the sage !

- Said the woman to the soldier. "

Günter Thimm nevertheless analyzes Eilif's separation from the family psychologically. In the “Song of Woman and Soldiers”, which Eilif sings first and which is then continued by his mother, the mother's warning of the dangers of the world outside of the family contrasts with male symbolism.

- "The rifle shoots,

- And those who wade in it eat up the water. ",

warns the female voice, while male motives lure the young man into the warlike world:

- “But the soldier with the bullet in the barrel

- Heard the drum and laughed at it:

- Marching can never do any harm!

- Down to the south, up to the north

- And he catches the knife with his hands!

- Said the soldiers to the woman. "

The leitmotif of the drum, "the oedipal symbolism ('ball in the barrel')", " lust for fear ('And he catches the knife with his hands!')" And aimless departure are characteristic of Eilif's departure from the family in tradition dad's. Returning to the family after starting the war seems impossible. When Eilif, tied up by the soldiers, hopes for his mother's help, she is absent to buy goods.

Gudrun Loster-Schneider sees here a task of “equating (age) wisdom and femininity, with which female figure and text advertise their position critical of the war; the woman's warning is only authorized in the version of the piece at the instance of 'old', nature-based, non-gender-specific knowledge (...) "

In the first stanzas of the "Song of Woman and the Soldier" (sung by Eilif), the optimism of a young soldier prevails who ignores or ignores a woman's warning and wades through the ice-cold water of a ford . The ice-cold water and the ford symbolize the dangers of war; the young soldier is confident, well armed, and optimistic. Courage counters these confident words with its stanzas with its warnings against boldness. The song foreshadows two phases in Eilif's life: his highest triumph and his shameful end. The soldier in the song goes "like smoke" and died in vain.

In their work Ungeheuer Brecht, Frank Thomsen, Hans-Harald Müller and Tom Kindt interpret the imagery of “river” and “cold”. The " phonetically linked and paratactically and parallelly lined up phenomena of war ('the rifle shoots' / 'the spear knife spears' / 'the water eats')" equated the threat from weapons and from the river. Because the soldier himself carries a knife, he is "not just a victim of the dangerous river", he makes a contribution to the dangers. This becomes clear through the "equation of the terms shooting rifle / spit knife / water". The cold metrics also show the soldier's share in the threat posed by the war. The dangerous ice of the river corresponds to the fact that the soldier laughs "coldly in the face" of the woman. Eilif's coldness shows itself later in the drama in the brutality with which he acts against the farmers.

The song must not be interpreted in such a way that the courage possesses clairvoyant abilities. Rather, in the song, Brecht uses the actress Courage as a mouthpiece to make a comment. The song functions as an element of epic theater and is primarily directed not at the fellow actors but at the audience.

Gudrun Loster-Schneider points out that the song brings two opposing worlds together in the double scene in the 2nd picture. While Eilif's heroic deeds are pathetically praised in the tent of the field captain, Courage and the cook hold their subversive speeches next door in the cook's tent. "The courage of plucking the captain's capon, meanwhile, dismantles this pathetic speech overheard in front of the cook on the courage to die , heroic virtue , Herculean deeds, loyalty and virtue of the team with cutting dialectics and measures it inversely proportionally to the performance deficits of the powerful and to 'properly ( n) 'Social conditions - in war as in peace. ”The song brings the two scenes together by becoming the“ medium of recognition,' password 'between mother and her lost son ”. The son sings the first two stanzas in the tent of the field captain, the mother continues the song from the kitchen.

The lyrics themselves are based on contrasts: In the “symbolic (power) confrontation of woman / wise / old vs. Soldat / reckless / daring ”the song offers two age- and gender-specific identification options as text in the text. Despite the warning from the death of his father in the war, Eilif identifies himself with the enthusiasm for war at the beginning of the song and ignores his mother's warnings. The fact that Courage recognizes the futility of her warning from the song is shown by the slap she gives her son.

Since the courage and thus the female position in the song and in the drama is right with her warning, Gudrun Loster-Schneider points out the possible gender-specific reading of the song: On a first level of interpretation, “the - positive - characteristic of historical change and progress will show the other, feminine side of the symbol arrangement has been shifted and can therefore be projected onto phenomena and discourses of emancipation for women (...) ”. On closer inspection, however, the emancipatory project also proves to be doomed to failure. “The emancipatory lesson that Anna Fierling learned for herself from the song about the woman and the soldier has not only catastrophic consequences for the happiness, health and life of her three children; According to Brecht's ideological premises since the 1930s, it is also wrong. "

The song of the great surrender

The basic attitude of courage towards war and society can be seen in the "Song of the Great Surrender": Young people's confidence, hope and joie de vivre give way to the daily struggle for survival. That means: “You have to face the people, one hand washes the other, you can't get your head through the wall… And they march in lockstep in the chapel…” (Scene 4: Courage instructs the young soldier, who still believes in justice that the anger does not last long because for the sake of business you have to capitulate at some point).

With the help of the individual stanzas one can understand the path of courage:

- The young, optimistic girl thinks she is something special and wants to shape her life on her own (“All or nothing, at least not the next best, everyone is their own fortune, I don't let any rules be made!”). ( Thesis )

- Experience shows that the high goals cannot be achieved, the living conditions do not allow it. Adaptation is the order of the day ( antithesis )

- Courage, which has already surrendered, conjures up optimism and self-confidence. Her experience has convinced her of the impossibility of swimming against the current (“you have to reach for the blanket”) . In the “chapel”, the individual has to fit in with the bigger picture, he has to march in step. ( Synthesis )

Tiny signals in the text show how the change takes place during the song:

The chorus in the first stanza is introduced with “yes” and addresses someone with “you”; What is meant is the courage itself, which at this point has not yet surrendered.

The second stanza says “she is marching”: the surrender has taken place.

The refrain in the third stanza already generalizes: “They march” - Courage has made a lesson from its experiences (synthesis of its opposing considerations).

The stanzas always end with

- "The human thinks, God leads.

- No talk of it. "

The colon indicates the error: Man cannot hope for the wise guidance of a divine authority, on the contrary, that is an illusion. Without divine help, man is dependent solely on his own strength. In its song, Courage offers the soldier three options:

- One rebels

- One tries to change the situation

- You adapt

This adaptation is the lesson that Courage gives the young soldier on the way. The contradiction between business interests and human emotions is insurmountable under the conditions of this society.

According to Franz Norbert Mennemeier, The Song of the Great Surrender shows “the course of life as the unstoppable disillusionment of all individual urges for something higher, as the unstoppable wear and tear of all special wishes for happiness.” With the rejection of divine guidance (“Man thinks: God directs - / No talk about it! ") The song shows" the picture of a world ... in which the small, human plans fail because the whole thing lacks planning and control ".

The Solomon Song

Brecht used the Salomon song , which Courage and the cook intoned for a warm soup in the 9th scene in front of the rectory, at the end of the 7th picture of his Threepenny Opera (1928). Brecht made major changes to the text for Mother Courage ; besides, he has another role in the drama. The basic idea of the song is that virtues are perishable to humans. Examples from history (Solomon, Caesar, Socrates and St. Martin) are intended to demonstrate this in parallel stanzas. The danger associated with the individual virtues now clearly relates to the children of courage. Caesar's boldness refers to the fall of Eilif, the honesty of Socrates to the death of the honest Swiss and the pity of St. Martin on Kattrin's act of rescue and her fate.

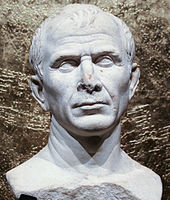

Eilif Nojocki is the bold son. The Feldhauptmann and the Solomon Song compare him to Julius Caesar . Especially in the song the threat contained in this comparison becomes clear:

- “You then saw the bold Caesar

- You know what became of him.

- He sat like God on the altar

- And was murdered, as you learned

- (...)

- The boldness had got him so far!

- Enviable who is free of it! "

Günter Thimm analyzes Eilif's detachment from the family psychologically. In the “Song of Woman and Soldiers”, which Eilif sings first and which is then continued by his mother, the mother's warning of the dangers of the world outside of the family contrasts with male symbolism.

- "The rifle shoots,

- And those who wade in it eat up the water. ",

warns the female voice, while male motives lure the young man into the warlike world:

- “But the soldier with the bullet in the barrel

- Heard the drum and laughed at it:

- Marching can never do any harm!

- Down to the south, up to the north

- And he catches the knife with his hands!

- Said the soldiers to the woman. "

The leitmotif of the drum, "the oedipal symbolism ('ball in the barrel')", " lust for fear ('And he catches the knife with his hands!')" And aimless departure are characteristic of Eilif's departure from the family in tradition dad's. Returning to the family after starting the war seems impossible. When Eilif, tied up by the soldiers, hopes for his mother's help, she is absent to buy goods.

Eilif perishes because he does not know when to be bold and when not. In the war he is considered a hero when he outwits, beats down and robbed an armed group of peasants because brutality in war is considered “normal” and “commendable”. He is later executed for the same act during a brief period of peace.

Brecht's Berlin production showed Eilif's boldness in the second scene with a saber dance, which is to be performed “both with fire and with nonchalance”.

Fejos, also known as Schweizeras, is the honest, honest son of Courage. His virtue is his undoing because, like his brother, he does not recognize the limits of the principle that he embodies. His attempt to save the Lutheran regimental treasury that was entrusted to him does not help anyone; so he sacrifices his life senselessly. The mother, who could have saved him by bribery, haggled too long, obeying her own principle, for the price of liberation.

The Solomon Song shows the fate of the honest using the example of the philosopher Socrates :

- “You know the honest Socrates

- Who always spoke the truth

- Oh no, they didn't thank him

- Rather, the superiors pursued him angrily

- And handed him the hemlock potion. "

The symbolic figure of the Kattrin is St. Martin , who shares his cloak with the beggar out of pity. As with the virtues of her siblings, the Solomon song sees selflessness and pity as a deadly danger:

- “Saint Martin, as you know

- did not endure the hardship of others.

- He saw a poor man in the snow

- And he offered him half his coat

- They both froze to death. "

Kattrin's sacrificial death in the 11th scene is also staged musically: To warn the sleeping city of Halle of the conquerors, she escapes with a drum on a roof and, according to Brecht's notes, drums in a two-stroke cycle that chants the word "violence". She "reworks the originally military instrument and uses it for the wake-up call to the city."

The cook Pieter Lamb performs the Salomon song and thus presents a central motif of the piece:

- "All virtues are dangerous in this world, they (...) don't pay off, only bad things, that's how the world is and doesn't have to be."

As clearly as the three middle stanzas relate to the children of Courage, it is difficult to assign the first stanza, the figure of the wise Solomon. Helmut Jendreiek considers a reference between the symbolic figure of wisdom and courage to be ruled out, since it is precisely this that does not recognize “that war does not bring the mass of ordinary people any profit and that a world order must be eliminated, one of which is war.” Jendreiek The symbolic figure of the wise Solomon relates more to the cook because of his insight, "that the world could also be different and that fear of God ruins people because it accepts world events as God-willed fate and excludes any active attempt to change the world." Jendreiek sees in this Reading an alienation effect, as the cook emphasizes that it is “enviable” to be free of such wisdom and that this requirement would also be met by not acting according to his understanding.

Kenneth R. Fowler rejects the various approaches to assign the figure of Solomon to one of the figures in the piece. The only function of the first verse is to formulate the thesis of the song and the central questions. The "great men" the song names as representatives of the virtues of the Courage children are largely meaningless placeholders. At no point does the wisdom represented by Solomon in the song specifically match the views of the biblical Solomon. If the biblical Solomon took the view that everything that happened in time was insignificant, then Brecht took exactly the opposite wisdom: that it was about changing the real world. Fowler sees the song in the context of questioning the great men of history. From this perspective, Salomon appears as an oppressor who carried out his great works on the back of slaves. His ascetic ethic then only serves to keep the exploited in their place.

From this perspective, Fowler interprets the other great men of the Solomon song as dubious symbolic figures for the virtues. In this way, Caesar and Eilif combine not only boldness, but also ruthless brutality towards the common people. In Caesar, Fowler also sees lines of connection to Hitler and refers to other works by Brecht such as The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar or Arturo Ui , which draw this parallel. For Fowler, the warning about the virtue of boldness not only encounters the danger it poses to its wearer, but also shows a fundamental rejection of martial heroism.

Fowler describes the connection between Socrates and Schweizerkas, between philosopher and fool, as malicious . Brecht rejected the martyrdom of Socrates in principle. As a patriot and devoted servant of the state, Socrates gave up flight and the fight for his ideas, which Brecht considered fundamentally wrong. Equally absurd is the loyalty of the Swiss to his regiment, which achieves nothing and leads to certain death. "In Brecht's eyes, Schweizererkas 'and Socrates' self-sacrifice are idiotic submission to an oppressive state."

The comparison of Kattrin with St. Martin makes a drastic change in the legend of the saints . If, in church tradition, the merciful act is the starting point for Martin's Christianization, his path to becoming a bishop and later becoming a saint, in Brecht's version the saint and the beggar freeze to death: In view of its unsuccessfulness, pity appears as a senseless virtue. Fowler sees Brecht's version as a critical view of Kattrin's rescue act for the city of Halle:

“The song makes it clear that Kattrin's virtue is also insufficient. Their sacrifice does not affect the greater evil, war, even if it refers more to the social and revolt than the virtues of their brothers, it remains the limited, desperate act of an individual. In this respect, their virtue is harmless and, as Brecht said elsewhere: 'Harmlessness is not good' because it perpetuates evil. "

Fowler sums up the intention of the song in such a way that Eilif's boldness promotes war, that honesty like that of the Swiss cheese serves the interests of the rulers and that Kattrin's passion and selflessness allowed a respite, but ultimately would not attack the basic evil. "Virtues like these are useless to the common people, just like Solomon's world-negating wisdom, as is the virtue of obedience (to God in fear of God and to civil authorities in 'ordinary people')." Fowler does not see Brecht's perspective in a world in which these virtues would make sense, but in the creation of a society in which these dubious virtues would be superfluous.

In view of the context and the people, contradictions stand out: can the cook who seduced Yvette and turned him into a warehouse whore, really fear God? Isn't he demanding that Courage should leave her daughter behind? And what about Mother Courage? The song about the uselessness of virtue is inserted into a scene that brings courage a little closer to the audience because it shows the virtue of motherly love by deciding on a grueling wandering life with her daughter and not alone with him Koch chooses the easy way to a reasonably secure life. It is also irritating that Brecht gives the impression that it is promising to expressly evaluate the lack of fear of God as something worth striving for if one wants to beg something to eat from a clergyman. Paradoxically, Mother Courage even succeeds with this type of argument.

How does what the characters sing and what they do fit together? The literary scholar Hans Mayer writes:

“The song proclaims the worthlessness of all noble emotions at the same moment as a really noble act takes place. So it is evidently not the fault of the virtues if people fail to benefit from them. So it must be special social conditions that cause disaster among the great, and especially among the little people. There are no "inherently" harmful virtues. "

Brecht deliberately demonstrates contradictions to the viewer; he wants to show him that he must not accept everything that he sees on stage without criticism, but must distance himself from what is happening. The Solomon song is therefore a good example of how epic theater works: the viewer is confronted with a problem, he studies it and is thereby forced to make decisions.

With the Salomon Song, Joachim Müller demonstrates the functional change in Brecht's songs. Initially, the song in the 9th scene of Courage is no longer sung in front of the curtain, but developed from the scene. The song is also linked to the plot through comments from the cook. “If there was a sharp intellectual caesura between the song and the scenic course in the Threepenny Opera , the function of the song, which is presented by the cook as Persona dramatis , proves to be dramatically necessary and specifically targeted in Courage .” Müller sees in the scenic Solomon -Song nevertheless the voice of Brecht, the song sums up the social knowledge in the sense of an appeal.

Other uses of Courage music

Immediately after completing the “American version” in 1946, Paul Dessau began to work on converting the incidental music into a purely instrumental piece in the form of a suite . On May 8, 1948, he completed the score for the suite. It was intended for 15 instruments: two flutes, three horns, three trumpets, three trombones, harmonica, prepared piano and timpani. The autograph has survived but has not been published. The first movement is titled March Fantasy and uses the song of Mother Courage . In 1956/1957, after Brecht's death, the piece was included in the second movement of Dessau's composition In memoriam Bertolt Brecht . This sentence is accompanied by a courage quote The war shall be cursed! named; the melody of Mother Courage's song here forms a kind of cantus firmus . The counterpoints on this theme are also composed of parts of the incidental music.

Dessau also used his Lied von der Bleibe twice anew. First he set it in 1954 for a three-part female choir, a year later he used the melody as the basis for the second movement of his 5th string quartet , Quartettino .

Sources

Simon Parmet's setting is lost. Parmet himself claims that he destroyed everything but one piece. His estate cannot be found, and the documents are no longer available from the Kurt Reiss theater publisher or from the participants in the premiere.

Paul Burkhard's version has not been published. However, there is a copy (piano reduction), presumably made by his wife, which is accessible in the Paul Burkhard Archive and various libraries and is also cited in the literature in excerpts. The autograph has not yet been found; the Paul Burkhard Archive, however, is still waiting for systematic processing.

Paul Dessau's American version from 1946 is only available as a manuscript. In 1949 he published two piano reductions of songs from Mother Courage ( seven songs for “Mother Courage and Her Children” and nine songs for “Mother Courage and Her Children” ), which represent two different stages of processing. A full score has existed since 1957, published by Henschel Verlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, but is only available as loan material for the stage and is not accessible in libraries.

literature

text

- Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. A chronicle from the Thirty Years War, in: Attempts , Heft 9 [2. Edition] (attempts 20–21), Suhrkamp, Berlin 1950, pp. 3–80 (20th attempt, modified text version).

- Mother Courage and her children . Stage version by the Berliner Ensemble, Henschel, Berlin 1968.

- Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and Her Children , in: Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 6): Pieces 6 Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 978-3-518-40066-1 , pp. 7–86.

filming

- Mother Courage and her children , DEFA film 1959/60, based on a production by Bert Brecht and Erich Engel in the Berliner Ensemble , with Helene Weigel , Angelika Hurwicz , Ekkehard Schall , Heinz Schubert , Ernst Busch and other ensemble members, film director: Peter Palitzsch and Manfred Wekwerth , music by Paul Dessau

Secondary literature

- Poet, composer - and some difficulties, Paul Burkhard's songs for Brecht's «Mother Courage» . In: NZZ , March 9, 2002

- Bertolt Brecht: Courage model 1949 . In: Schriften 5, Berliner and Frankfurter Edition, Vol. 25. Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1994, pp. 169–398

- Gerd Eversberg : Bertolt Brecht - Mother Courage and Her Children: Example of Theory and Practice of Epic Theater . Beyer, Hollfeld 1976

- Kenneth R. Fowler: The Mother of all Wars: A Critical Interpretation of Bertolt Brecht's Mother Courage and Her Children . Department of German Studies, McGill University Montreal, 1996. A thesis subntitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

- Werner Hecht: Materials on Brecht's “Mother Courage and Her Children” . Frankfurt am Main 1964

- Fritz Hennenberg: Dessau - Brecht. Musical work . Edited by the German Academy of the Arts . Henschelverlag, Berlin (GDR) 1963.

- Fritz Hennenberg (ed.): Brecht song book . Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-37716-7

- Fritz Hennenberg: Simon Parmet, Paul Burkhard. The music for the premiere of “Mother Courage and Her Children” . In: notate . Information sheet and bulletin from the Brecht Center of the GDR. 10 (1987), H. 4, pp. 10-12. (= Study No. 21.)

- Fritz Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties. Paul Burkhard's songs for Brecht's “Mother Courage” . In: NZZ , March 9, 2002.

- Helmut Jendreiek: Bertolt Brecht: Drama of Change . Bagel, Düsseldorf 1969, ISBN 3-513-02114-3

- Jan Knopf: Brecht manual, theater . Unabridged special edition. Metzler, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-476-00587-9 , Notes on Mother Courage, pp. 181-195

- Gudrun Loster-Schneider: From women and soldiers: Balladesque text genealogies from Brecht's early war poetry . In: Lars Koch; Marianne Vogel (Ed.): Imaginary worlds in conflict. War and history in German-language literature since 1900 . Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8260-3210-3

- Joachim Lucchesi : “Emancipate your orchestra!” Incidental music for Swiss Brecht premieres . In: Dreigroschenheft , Volume 18, Issue 1/2011, pp. 17–30 (previously published in: dissonance . Swiss music magazine for research and creation, Issue 110 (June 2010), pp. 50–59.)

- Krisztina Mannász: The epic theater using the example of Brecht's mother Courage and her children: The epic theater and its elements in Bertolt Brecht . VDM Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-639-21872-5 , 72 pp.

- Franz Norbert Mennemeier: Mother Courage and her children . In: Benno von Wiese: The German Drama . Düsseldorf 1962, pp. 383-400

- Joachim Müller: Dramatic, epic and dialectical theater . in: Reinhold Grimm: Epic Theater . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1971, ISBN 3-462-00461-1 , pp. 154-196

- Klaus-Detlef Müller: Brecht's “Mother Courage and Her Children” . Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 3-518-38516-X (extensive anthology with articles and other materials).

- August Obermayer: The dramaturgical function of the songs in Brecht's mother Courage and her children . Commemorative publication for EW Herd. Ed. August Obermayer. University of Otago, Dunedin 1980, pp. 200-213.

- Theo Otto: sets for Brecht. Brecht on German stages: Bertolt Brecht's dramatic work on the theater in the Federal Republic of Germany . InterNationes, Bad Godesberg 1968

- Andreas Siekmann: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-12-923262-1 .

- Dieter Thiele: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children . Diesterweg, Frankfurt 1985

- Günter Thimm: The chaos was not gone. An adolescent conflict as a structural principle of Brecht's plays . Freiburg literature-psychological studies, Vol. 7th 2002, ISBN 978-3-8260-2424-5

- Friedrich Wölfel: The Song of Mother Courage. Ways to poem . Schnell and Steiner, Munich 1963, pp. 537-549.

Web links

- Bertolt Brecht: The Epic Theater (around 1936)

- Bertolt Brecht: About experimental theater (1939)

- Bertolt Brecht. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Mother Courage and her children (synopsis) (PDF; 50 kB) Proseminar at the University of Würzburg

- Manfred Wekwerth: What does reality actually mean on stage? or The real chances of the theater . In: Marxistische Blätter , 4/2009

- detailed text on lit.de.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” 2011, p. 19; Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties .

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 428.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 405f.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , Pp. 17–30; Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties ; Hennenberg: Brecht song book , pp. 430–433.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 429.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , P. 20; Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties .

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 429; Jan Knopf: Brecht manual. Theater , p. 192.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , Pp. 20f., 22; Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties .

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , P. 22; Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties .

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , P. 22; Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties .

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , Pp. 22-26.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate your orchestra!” , Pp. 23–26.

- ↑ This list is evaluated by Lucchesi: “Emancipate your orchestra!” , Pp. 24–26.

- ^ Hennenberg: poet, composer - and a difficulty .

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate your orchestra!” , P. 24.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , P. 26.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate Your Orchestra!” , P. 24, based on Burkhard's notebooks and diaries.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 430.

- ↑ Lucchesi, Shull: Music with Brecht . 1988, pp. 54f.

- ↑ Lucchesi, Shull: Musik bei Brecht , p. 82.

- ↑ See for example the two first publications of the songs, Sieben Lieder aus der Mutter Courage and Neun Lieder aus der Mutter Courage , both in 1949, where this instruction is drawn together by Brecht and Dessau.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate your orchestra!” , Pp. 26–28.

- ^ Fritz Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 434.

- ^ Letter to Dessau, January 1, 1949, cited above. based on: Lucchesi, Shull: Musik bei Brecht , p. 220.

- ↑ Lucchesi, Shull: Musik bei Brecht , pp. 703 and 708f.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 434f.

- ↑ Thomas Phleps: Guernica in Exile . In: Klaus Angermann (Ed.): Paul Dessau: From history drawn. Symposium reports of the Hamburg Music Festival. Symposium Paul Dessau Hamburg 1994 . Wolke Verlag, Hofheim 1995, pp. 71-100, here: pp. 77f.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Joachim Lucchesi: Sung Texts. Questions to the new Brecht research. In: Dreigroschenheft , 2/2007, pp. 26–33.

- ↑ The scene overview is printed in: Jan Esper Olsson: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. Historical-critical edition . Liber Läromedel, Lund; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1981, p. 112.

- ↑ Quoted here from Albrecht Dümling: Let not be seduced , p. 456.

- ↑ Brecht: Couragemodell 1949 , notes, p. 6.

- ↑ Brecht: Courage model 1949 . Notes, p. 6

- ↑ Brecht: Courage model 1949 . Notes, p. 6.

- ↑ Brecht: Courage model 1949 . Notes, p. 6.

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht: Poems 2. BFA Volume 12, p. 330.

- ↑ Müller: Dramatisches, Episches und Dialektisches Theater , p. 171.

- ↑ Müller: Dramatisches, Episches und Dialektisches Theater , p. 171.

- ↑ Müller: Dramatisches, Episches und Dialektisches Theater , p. 171.

- ↑ Jendreiek: Bertolt Brecht: Drama of Change , p. 200

- ^ Walter Hinck: The dramaturgy of late Brecht , p. 42

- ^ Walter Hinck: The dramaturgy of late Brecht , p. 42

- ^ Walter Hinck: The dramaturgy of late Brecht , p. 43

- ^ Walter Hinck: The dramaturgy of late Brecht , p. 45

- ^ Walter Hinck: The dramaturgy of late Brecht , p. 47

- ↑ Quoted from Hennenberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 430.

- ^ After Hennenberg: Poet, composer - and some difficulties .

- ↑ Dessau: On Courage Music , p. 122.

- ↑ James K. Lyon: Brecht unbound . Presented at the International Bertolt Brecht Symposium, held at the University of Delaware, February 1992, International Bertolt Brecht Symposium (1992, Newark, Del.), Newark, Delaware Univ. of Delaware Pr. [u. a.] 1995, p. 152.

- ↑ Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced , p. 457.

- ↑ Quoted from Hennenberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 368f.

- ↑ Cf. Dieter Baacke, Wolfgang Heydrich: Glück und Geschichte. Notes on the poetry of Bertolt Brecht . In: Text and criticism : Bertolt Brecht II, 1979, pp. 5–19, here: p. 11.

- ↑ Quoted from: Hennenberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 361.

- ^ Matthias Tischer: Composing for and against the state , p. 107.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , p. 227.

- ↑ Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced , p. 553.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , p. 227.

- ↑ See especially: Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , pp. 225–228.

- ↑ See for example Hennenberg: Brecht-Liederbuch , p. 367 (commentary on the ballad “Apfelböck or the lily on the field” from the same period).

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , p. 227f and p. 406.

- ↑ Gerd Rienäcker: Analytical remarks on orchestral music "In meomoriam Bertolt Brecht" by Paul Dessau . In: Mathias Hansen (Ed.): Musical analysis in discussion , Berlin 1982, pp. 69–81; quoted here from: Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 108.

- ↑ Cf. Rienäcker, quoted from Tischer: Composing for and against the state . P. 108.

- ^ According to Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 108f.

- ↑ Tischer: Composing for and against the state , p. 108.

- ↑ Rienäcker, quoted from Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 109.

- ↑ Bert Brecht: The ballad of the soldier . In: Hauspostille , Grosse Annotated Berlin and Frankfurt Edition, Vol. 11, Poems 1, pp. 98f.

- ↑ quoted from: readbookonline

- ^ Bert Brecht: Gedichte 1 , p. 319

- ↑ The drama should be called "Calcutta"; see. Gudrun Loster-Schneider: From women and soldiers , p. 64.

- ↑ Gudrun Loster-Schneider invokes: Albrecht Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced. Brecht and the music . Munich 1985; see. Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 64.

- ↑ Albrecht Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced. Brecht and the music . Munich 1985, p. 130; quoted from: Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von Weibern und soldiers , p. 65.

- ↑ Bert Brecht: The ballad of the soldier . In: Hauspostille , Grosse Annotated Berlin and Frankfurt Edition, Vol. 11, Poems 1, p. 99

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 24

- ↑ Mother Courage , 3rd scene, p. 23f.

- ↑ both: Mother Courage , 3rd scene, p. 24.

- ↑ Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 65

- ↑ Frank Thomsen, Hans-Harald Müller, Tom Kindt: Ungeheuer Brecht. A biography of his work . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006, ISBN 978-3-525-20846-5 , p. 258

- ↑ Ungeheuer Brecht , p. 258.

- ↑ Ungeheuer Brecht , p. 258.

- ↑ Ungeheuer Brecht , p. 258.

- ↑ Ungeheuer Brecht , p. 259.

- ^ Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 59.

- ^ Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 59.

- ↑ Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 60.

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 25.

- ↑ Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 62.

- ↑ Gudrun Loster-Schneider: Von women and soldiers , p. 62.

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 48ff. (Scene 4)

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 49 (scene 4)

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 49

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 50

- ↑ Mother Courage , p. 49f. (Scene 4)

- ^ Franz Norbert Mennemeier: Modern German Drama. Reviews and characteristics . Volume 2, 1933 to the present, Munich 1975, 2. verb. u. exp. Berlin 2006, p. 233, quoted from: Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 107.

- ^ Franz Norbert Mennemeier: Modern German Drama. Reviews and characteristics . Volume 2, 1933 to the present, Munich 1975, 2. verb. u. exp. Berlin 2006, p. 233, quoted from: Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 107.

- ↑ "Field Captain: There is a young Caesar in you"; Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children , 2nd scene, p. 23.

- ↑ Mother Courage , 9th scene, p. 75.

- ↑ Mother Courage , 3rd scene, p. 23f.

- ↑ both: Mother Courage , 3rd scene, p. 24.

- ↑ Brecht: Couragemodell 1949 , p. 192.

- ↑ Mother Courage , 9th scene, p. 75f.

- ↑ Mother Courage , 9th scene, p. 76

- ^ Irmela von der Lühe, Claus-Dieter Krohn : Fremdes Heimatland: Remigration and literary life after 1945 , Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2005.

- ↑ Mother Courage , pp. 75f.

- ↑ Helmut Jendreiek: Bertolt Brecht , p. 184.

- ↑ Helmut Jendreiek: Bertolt Brecht , pp. 184f.

- ↑ Helmut Jendreiek: Bertolt Brecht , p. 185.

- ^ Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , pp. 356f.

- ↑ (“… are willing to take at face value the authority of Solomon, a king - and so an oppressor - whose great works were carried out on the backs of siaves, an exploiter who (like others, such as Puntila) preaches a conveniently ascetic ethic that would keep the exploited in their place. "); Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 358

- ^ Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 361

- ↑ ("Here is a wicked combination, Socrates and Schweizerkas, philosopher and fool."); Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 363.

- ↑ ("Yet when Socrates 'friends arranged the escape (as Athenians probably expected), Socrates refused it. No doubt Brecht, who was neither a patriot nor an obedient son of the State, would have found Socrates' reasons for this refusal perverse: “); Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 364

- ↑ ("In Brecht's eyes, then, Schweizerkas's and Socrates' self-sacrifices are foolish submissions to an oppressive State."); Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 365 (translation: Mbdortmund).

- ↑ ("The song, then, makes it clear that Kattrin's virtue is also insufficient. Her self-sacrifice does not touch the greater evil, war, and if it suggests the social and hints at revolt more than do the virtues of her brothers, still it is the limited, desperate act of an individual. To that extent her virtue is harmless, and, as Brecht said elsewhere: 'Harmlessness is not goodness,' for it perpetuates evil. "); Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 372 (translation: Mbdortmund).

- ↑ (“Boldness like Eilifs which fuels war, Honesty like Schweizerkas's which loyally supports the interests of the rulers. Compassion and Selflessness like Kattrin's which provide a temporary respite but do not touch the source of evil; virtues such as these are of no use to the little people, no more than is Solomoo's world-denyiog wisdom, no more than has been the virtue of obedience (to God in Gottesfurcht , and to civil authority by remaining 'ordinary people'). "); Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , p. 372 (translation: Mbdortmund).

- ^ Fowler: The Mother of all Wars , pp. 373f.

- ↑ Hans Mayer: Notes on a scene from Mother Courage . In: German literature and world literature , Berlin 1957, pp. 335–341.

- ↑ Joachim Müller: Dramatisches, Episches und Dialektisches Theater , p. 173.

- ^ Daniela Reinhold: Paul Dessau. Documents zu Leben und Werk , 1995, p. 73 (documents 97 and 98), see also Figure 22, which shows the title page of an early version of the suite. On In memoriam Bertolt Brecht and the processing of stage music there: Matthias Tischer: Composing for and against the state , in particular pp. 107–113.

- ^ Fritz Hennenberg: Dessau - Brecht , p. 450f.

- ↑ Cf. on Parmet and Burkhard in particular: Lucchesi: "Emancipate your orchestra!"

- ^ Hennenberg: Dessau - Brecht , p. 449.