The business of Mr. Julius Caesar

The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar is an unfinished work by the German writer Bertolt Brecht , which was originally supposed to consist of six books. Brecht worked on it from 1938 to 1939 while in exile in Denmark. In 1949 the second book in the series "Our Lord C." was published in the magazine Sinn und Form (Berlin). In 1957 the third book “Classic Administration of a Province”, also in its meaning and form , and the entire fragment (books 1–4) were published posthumously by Gebrüder Weiss Verlag (Berlin / West) and Aufbau Verlag (Berlin / GDR).

The novel is one of Brecht's lesser-known works. Nevertheless, the importance of the fragment in general and within Brecht's oeuvre should not be underestimated: The business of Mr. Julius Caesar is on the one hand an example of the genre of the historical novel of the interwar period, but on the other hand the work represents the transfer of the alienation effect from the field of epic theater on the novel and particularly reveals Brecht's understanding of history as a “perspective of the other side”.

The main plot of the novel describes the time from Caesar's participation in the Catilinarian conspiracy (691 Roman era or 63 BC) to his governorship in Spain and his subsequent application for the consulate (694 Roman era or 60 BC) . Chr.). The main plot is embedded in a framework narrative that reproduces the plan of a young lawyer to write a biography about Caesar, who was murdered twenty years earlier.

N. B. The following explanations are based on the following text edition: Werner Hecht, Jan Knopf u. a. (Ed.): Bertolt Brecht. Prose 2. Fragments of novels and drafts of novels (= Bertolt Brecht. Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions. Volume 17). Frankfurt am Main.

Contents overview

Structure (narrative and time levels)

The novel is divided into six books, with Brecht only fully elaborating the first three books and the beginning of the fourth book. The narrated and experienced events can be assigned to three narrative levels: The first two are part of the framework story; it is the level of the young lawyer who sets out the framework from the first-person perspective, and the level of Mummlius Spicer. The latter remembers his dealings with Caesar in his conversations with the first-person narrator . Since the first-person narrator (the young lawyer) for his part reproduces these memories in the frame narration, Spicer's narrative level is to be set within that of the first-person narrator. The third narrative level is made up of the diary entries of Caesar's secretary named Rarus, which represent the actual main plot. The narrative level of Rarus is thus detached from the other two narrative levels.

The division of the narrative levels is roughly the same as that of the time levels: The first two time levels consist of the reports of the narrator and the other characters in the plot (Mummlius Spicer, Afranius Carbo, Vastius Alder, a legionnaire of Caesar). In retrospect, the narrator reports on his experiences at Spicer, which lasted three days and can be found around the year 730. While the characters in the frame narrative are at a considerable distance from the events described by Rarus, Rarus himself writes down his experiences immediately after their occurrence. The characters in the frame narrative and Rarus represent the same years in Roman history, but their perspective is different. According to Herbert Claas, the short but existing time gap between the framework plot and the events of the Catiline conspiracy enables, on the one hand, a completed legend ; So the Caesar myth has already grown. On the other hand, according to Claas, the interviewees of the first-person narrator could be considered contemporary witnesses, which gives their reports a certain “fictional authenticity”. The Roman calendar itself, which Brecht uses throughout the entire novel, finally appears as part of that fictitious authenticity.

Book 1: "Career of a distinguished young man"

The first book of the fragment “Career of a Noble Young Man” includes the framework of the novel: A young lawyer, the first-person narrator, decides to write a biography about Caesar who was murdered 20 years ago. To do this, he visits Mummlius Spicer, Caesar's former banker , who lives eleven days' journey from Rome in a villa on a wealthy estate run by slaves . He asks Spicer to hand over the diaries of the slave Rarus, a secretary of Caesar, which he believes are in Spicer's possession.

Spicer first plays a game with the first-person narrator by initially claiming that he had thrown the diaries away, then declaring that the lawyer had absolutely no use for them, and finally demanding the exorbitant sum of 12,000 sesterces for the loan of the diaries, under the Condition that the first-person narrator takes into account Spicer's "explanations" on the diaries. Angrily, the young lawyer agrees. In the further course of the plot, which takes up a period of a few days, the first-person narrator receives from Spicer both first reports about the situation in Rome at the time when Caesar entered the political stage, as well as about Caesar himself. Spicer tells him in one Manners, which the lawyer describes as “indifferent” (p. 178, line 32) and “shameless” (p. 187, line 9), of Caesar's relationship to the so-called “City” (upper class of merchants in Rome), of Caesar's first failed attempts as a lawyer and his encounter with the pirates of Asia Minor (the famous "pirate anecdote"). The narrator later meets other people who tell him about Caesar, including a former legionnaire from Caesar's army and the lawyer Afranius Carbo, who tells of the economic conflicts in Rome during Caesar's time. The first book closes with an overview of Caesar's entire career given by Spicer, which is also to be understood as a rough outline of the following books.

Book 2: "Our Mr. C."

The second book "Our Lord C." reproduces the first part of the diary entries of Caesar's secretary Rarus. The records contain the events of August through December of 691 (i.e. 63 BC). Rarus focuses on describing Caesar's financial and interpersonal difficulties. The focus here is on the conspiracy of Catiline and Caesar's role within this conspiracy. In addition, the private businesses of Caesar and Crassus are described.

The Roman Republic is in turmoil, the factional battles between the city and the senate (consisting of the class of rich landowners ) form the framework of the Catilinarian conspiracy. Caesar and Crassus are officially on the side of the city, but use the unrest for ominous grain trade and property speculation. The city, which is in a dispute with the Senate over the conquest of Asia Minor, tries to force a dictatorship of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus . The purpose of this dictatorship, the details of which City and Pompeius agreed in advance, is to break the (economic) power of the Senate. To this end, Pompey is supposed to prevent Catiline from his revolt. In order to justify the motion and the proclamation of dictatorship, the city artificially augments Rome's economic hardship and promotes Catiline's conspiracy. In the end, however, the city withdraws from its trade with Pompey for fear of Catiline. After Catiline's failed application for a consulate, the defeat of Catiline was taken over by the Senate, which emerged victorious from the factional battles. Since Caesar (as well as Crassus to a limited extent) had speculated on the City's victory, he is now confronted with a high level of debt. At the same time, he faces political and legal reprisals because of his support for Catiline.

The mood among the people has meanwhile turned against Catiline and one speaks only of "defending against the dictatorship" (p. 280, line 28). The so-called “Sturmrotten” and “street clubs”, in which the supporters of Catiline from the lower classes had come together, are disbanded and their members arrested. During the unrest, the stock market crashes , and there are various speculations about the reasons for this economic collapse. Caesar escapes his political ostracism by leading the trials against the Catilinarians himself after successfully running for the office of praetor . In this way, he can at the same time override all suspicions against himself. The entire second book testifies to the complexity of the content, which is based on the fact that Rarus himself lacks an overview and a deeper understanding of the events. Rarus (and thus also the reader) only learns the resolution and the background of the events from Caesar himself at the end of the second book.

Book 3: "Classic Administration of a Province"

The third book, "Classical Administration of a Province", deals more intensively with Caesar's machinations during and after the end of the Catiline conspiracy. It is divided into the brief notes of Rarus this time and the subsequent oral additions by Spicer. Caesar , who hopes for the return of Pompey and his army and consequently relies on a new settlement program (hence the property speculation), as praetor removes the evidence of his participation in the Catiline conspiracy. However, since Catilina's army is prematurely destroyed, a dictatorship of Pompey or his intervention with his own army is unnecessary. Pompey therefore returns to Rome without an army, which causes his popularity to decline immensely among the people: a solution to the land question and the economic problems through a possible seizure of power by Pompey is impossible. Caesar is now faced with massive debt stemming from his property speculation. Since he no longer enjoys his official protection after the end of his term of office, he resigns as governor in Spain .

A second, parallel storyline is Rarus' journey to the battlefield of Pistoria , the place of Catiline's defeat, where he goes on a futile search for his lover Caebio. His mourning for Caebio is the reason why the second part of Rarus' notes is relatively short, which is why Spicer's story is being supplemented. In addition, the first-person narrator encounters the poet Vastius Alder, who spreads about the historical significance of Caesar and his relationship to the Senate and City. In conclusion, Spicer reports on the financial consequences of the Catiline conspiracy and Caesar's flight to governorship in Spain.

Book 4: "The three-headed monster"

The fourth, incomplete book contains Rarus' notes about Caesar's return from Spain and his subsequent application for the consulate . Caesar has achieved considerable success in Spain, mainly financial. In order to guarantee his election as consul the greatest possible chance of success, he is planning a triumphal procession as an election campaign. However, since the high financial costs of the triumphal procession could not be paid from the Spanish income, Caesar was delayed in Spain by entanglements with the Roman bankers (whose money Caesar was dependent on for the execution of the triumphal procession). He can no longer come to Rome before the time to apply for a consulate, in which he is allowed to enter the city before the triumphal procession. Therefore, he decides to forego the triumphal procession, which in turn results in high financial losses for him (since he has already used large sums of money in preparation for the triumph). Skilfully and opportunistically calculating, however, he uses the mood of the people against wars and conquests that has meanwhile emerged and, in contrast to his original plan (for which the triumphal procession would have been necessary), presents himself as a peace-bringer instead of a general. The fourth book ends here .

The conceptual design of the last three books

The actual subject of the fourth book should consist of the 1st triumvirate , hence the title "The three-headed monster". From Brecht's notes it emerges that the focus in the conceptual design continues to be based on Caesar's “financial” motivations (p. 349, lines 11–12): The solution to the land question through the Lex Julia is “exposed” as “a gigantic property speculation by the historical triumvirate ”(p. 349, lines 17-18), with Caesar facing growing debts despite“ abuse of office ”. Furthermore, the "true value" of political legality within the Roman state is to be exposed by the fact that Caesar's actions are largely recognized as legal (p. 349, lines 37-38).

The further action describes the establishment of the "Gallic trading company" and the flight of Caesar before charges (after the end of the consulate) to the Gallic province. The private love affairs of Rarus are also spun on, whereby the fates of his two new lovers are conceived as representative of the Roman people (p. 350, lines 31–33). The Gallic War forms the content of the fifth book, which, according to Brecht, is conceived as the “most idyllic” of the six books (p. 351, lines 26-27). Here, too, Caesar's economic machinations are dealt with in more detail: he consciously tries to delay the end of the war in order to derive the greatest possible profit from his governorship in Gaul . Brecht's notes on the content end with a description of Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon and his return to Rome, as well as an outlook on the gloomy future of the Roman state.

Characters of the novel

Figures of the framework story

The characters in the framework plot are in all parts non-real characters conceived by Brecht, each of which serves different purposes within the conception of the novel. They cannot be traced back to any historical person.

The first-person narrator

The young, nameless lawyer, who has made it his task to write a biography about the great politician Gaius Iulius Caesar , is the central mediator between the events and the reader for the framework narrative. This becomes clear right at the beginning of the novel The intention of the first-person narrator with his biography, namely the unveiling of the Caesar legend and the disclosure of the true motives for the actions of the statesman Caesar ("There was the legend that obscured everything. He even wrote books to deceive us . […] The great men sweat before realizing the real motives for their deeds ”, p. 167, lines 19-23). The first-person narrator is aware of the dubious truthfulness of the reports by and about Caesar. Nevertheless, he is initially convinced of the glorious past of the politician whom he regards as his idol (p. 171, line 32). The indifferent and shameless portrayal of Caesar on the part of Spicer arouses particular outrage in him (p. 178, lines 31–35). Later, the first-person narrator shows anger and indifference to what he sees as pejorative statements by Spicer (p. 187, lines 17-19). The attitude of the first-person narrator to Caesar's person or to Spicer's statements is subject to a change of heart. However, only the narrator's growing doubts about the figure of Caesar and his own biographical project are fully explained (p. 320, line 23). Due to the perspective of the first-person narrator and the subjectivity of his portrayal, the reader is unavoidable to identify with the young lawyer. The aforementioned slow change of heart of the first-person narrator is designed by Brecht in such a way that it can be transferred one-to-one to the reader and contributes to the “unveiling” of the Caesar legend.

Mummlius Spicer

Just like the other characters of the framework story, Mummlius Spicer is characterized by the impressions and assumptions of the first-person narrator. Spicer, Caesar's former creditor and banker , has obviously profited from Caesar's business: he owns a rich, slave-managed estate with olive and vineyards and a simple, rural villa with a library (pp. 167–168). Outwardly, Spicer is described as tall, bony, and with his body bent over; the handling of the letters of recommendation that the narrator shows him refer to Spicer's profession (he goes through the lawyer's recommendation papers very carefully, p. 167, lines 35-38).

The narrator also often speaks of Spicer as "the old man". This attribute gives Spicer some authority over his life experience; the first-person narrator also emphasizes Spicer's modesty (p. 167, lines 25-29). On the other hand, Spicer's reports are again characterized by a mixture of indifference and omniscience: The first-person narrator reports on the banker's apparent indolence when he tells the story (p. 180, lines 3-14). Nevertheless, Spicer at the same time sees through the motives of Caesar's and the City's deeds in a remarkable way (e.g. BS 186, line 38 to p. 187, line 7).

The importance of Spicer for and within the conception of the novel becomes clear on closer examination of his attitude to historiography: Spicer himself expresses himself disparagingly in several places about the Roman historians (p. 169, lines 25-26, p. 172, line 15 -17). For Brecht, Spicer thus becomes the “mouthpiece” through which he can express a fundamental criticism of previous historiography (regarding Caesars).

Other people

Within the framework of the narrative, the first-person narrator encounters three other, briefly outlined people who all present their own opinions about Caesar. First he meets an old legionnaire who lives in a hut with a slave; He earns his living with a small olive business and occasional fishing. The lawyer does not learn much from the veteran (p. 189, lines 10, lines 26-27). The narrator does not receive a satisfactory answer for his opinion regarding Caesar's popularity with the common soldiers either (p. 189, lines 30–36). The legionnaire's further explanations regarding his fate as a soldier in the civil war make him appear as a typical representative of the lower social classes, who only have the alternative between a life as a soldier or a life as a farmer on a piece of land that is basically too small for arable farming appears. In Brecht's conception, the legionnaire personifies the common people "exploited" by capitalism .

The other two people the first-person narrator meets in the further course of the framework are the lawyer Afranius Carbo and the poet Vastius Alder, both wealthy and successful men of the Roman state. Carbo initially delights the narrator with flattery and praise for his plan to write a biography of Caesar (p. 192, lines 8-14). This joy soon turns into disappointment at Carbo's apparently “superficial” and “contestable” way of portraying the person of Caesar (p. 193, lines 3–4). Soon, however, the hypocritical type of Carbos reveals itself (p. 195, lines 37 to p. 196, line 3).

It is very similar with Alder: the narrator describes his appearance as that of a mummy (p. 303, lines 11-14) and he relativizes his military fame as well as his poetic achievements (p. 303, lines 14-23) . Spicer's disparaging remarks regarding the poet do the rest (p. 306, lines 31–35; p. 307, lines 14–20). Overall, the other characters in the frame narrative complement Spicer's function: although the first-person narrator is disparagingly against their own statements, they are nevertheless representatives of certain groups of people who each illustrate the negative sides of Caesar's story in their own way, the legionnaire as the "exploited", Carbo and Alder as "exploiter".

Characters of the main plot

In contrast to the main storyline, the characters in the main storyline are based on real historical personalities, apart from Alexander, Crassus' librarian, and Rarus and his lovers Caebio and Glaucos. The actual properties of the historical figures are, however, modified to a greater or lesser extent in line with Brecht's claim to validity. Therefore, their representation does not offer any “documentation” of the real historical actors.

Rarus

The figure of Rarus, Caesar's slave and secretary, forms the narrative instance of the main plot: His diary entries correspond to the text of the second and in parts of the third and fourth books of the novel; in addition to Spicer, Rarus essentially takes on the characterization of Caesar. Within the elaborated parts of the novel, Rarus himself is on the one hand characterized by Spicer, whose utterances are reproduced by the narrator without comment or evaluation. On the other hand, the reader learns a lot about Rarus through his own statements in his diary entries.

Rarus is characterized, among other things, by Spicer's statements to the first-person narrator: Spicer indicates that Rarus mainly documents the “business side” of Caesar's biography and that the reports cannot be used without explanations (p. 169, lines 19-20 , Lines 24-25). These statements by Spicer about Rarus already make clear in the framework plot (and are confirmed in Rarus' notes) that Rarus only understands the actions of Caesar, the City and the Senate when Caesar explains them to him himself (p. 284, lines 11-13 ). The second character trait that Spicer's remarks alluded to is Rarus 'sense of private affairs: In addition to Caesar's “women's stories”, he gives a lot of space in his notes to his relationship with Caebio, which is also Rarus' sensitivity and a certain naivety in turn revealed (especially when looking for Caebio on the battlefield of Pistoria). Rarus' lack of a sense of reality complements his lack of understanding of Caesar's strategies and business. Rarus himself does not seem to be aware of these character traits, as he believes that he is superior to other slaves and above all to Caesar's clients (p. 202, lines 25-30).

It is precisely the interaction of these three central characteristics of Rarus that explains its importance for the novel: Not only is the reader forced to concentrate on following the plot due to the complexity of the content of the diary entries; Even with the naive and sometimes even ignorant, unrealistic attitude of Rarus, Brecht succeeds in depicting a group of society that cannot understand the plight of the lower classes of the population.

Gaius Julius Caesar

The main character in The Business of Mr Julius Caesar , Gaius Iulius Caesar himself, never appears personally within the novel: he is always indirectly characterized, either by the person who spoke to the first-person narrator in the main story or by Rarus' diary entries (descriptions of the business Caesars, reproduction of dialogues, speeches etc.). Caesar thus becomes the object of the representations of several narrators, who each give their reports different subjective impressions.

The focus of the novel is determined from the outset by the choice of the narrator on Caesar's financial affairs, Rarus as Caesar's secretary, Spicer as the politician's banker . Caesar's finances and his business calculations also occupy a central place in the characterization of his person. Caesar's chronic debt burden is a recurring theme in the novel. The “careless handling” of money described at the beginning is almost turned into an addiction to waste (p. 201, lines 11–23, p. 252, lines 4–5). However, Caesar acts calculatingly and calmly in all business ventures, regardless of their respective success (p. 286, lines 1–4). Caesar's “Comedy” in the Senate is particularly exemplary in this regard (p. 289, line 7 to p. 299, line 3). For Caesar, politics is therefore only a means to an end in order to finance his debts and his lavish lifestyle.

Caesar's relationship with Crassus is in turn based directly on Caesar's business and political calculations, Crassus being instrumentalized by Caesar. In the close connection between finances and political calculation, Caesar's chronic debts appear as a conscious strategy (p. 307, lines 35–38, p. 308, lines 4–14). For Caesar the debt is a means to an end, that is, an instrument of political advancement. This debt strategy appears as an element of Caesar's opportunism, which also arises from his political calculation: as long as he is guaranteed political success, he is indifferent to the political direction. He always changes his attitude towards the side of the (supposed) winner, sometimes he supports the city, sometimes Catiline , sometimes the people, but ultimately he always acts in favor of his own goals, in which politics appears as an "object" of financial interests.

His relationship to the city and to the people also appears to be significant for characterizing Caesar (p. 173, line 7, p. 343, lines 10–11, p. 342, lines 21–35). The attitude of the people towards Caesar is interesting insofar as it stands in a certain contrast to Rarus' image of Caesar, partly as a glorification, partly as a denigration of Caesar; thus it forms a not unimportant further level of the Caesar representation in the novel. Because of displeasure and fickleness, the people remain a shapeless mob that can easily be seduced by skillful demagogy. Caesar himself endeavored especially before the consulate elections to gain the people's favor, made concessions (p. 293, lines 3–9) and organized games without, however, showing any real interest in the needs of the people. Caesar's relationship to the city is similarly ambivalent: At first, Caesar only remained a “stooge” of the city (pp. 177–178), but later he loosens his ties and also turns the city into an instrument of power in parts. As the novel progresses, it turns out that the reader can hardly differentiate who is instrumentalizing whom and who is whose "plaything". Only with the general clarification of the events by Rarus at the end of the second book does Caesar's superiority become clear (pp. 284–287).

Whenever Caesar finds himself in a position that makes it necessary to withdraw from the public for a while, he goes on a more extensive journey: After his failure as a lawyer in his younger years, he goes to Rhodes as is well known ; When Caesar got into political and financial distress because of Catiline's activities and his involvement in them, he withdrew to his governorship in Spain (p. 310–313). These “escapes” of Caesar are also directly related to his political and financial plans and calculations.

The conclusion that Rarus now draws about Caesar's political abilities (p. 286, lines 35 to 287, line 4) is, in Spicer's opinion, too pessimistic (p. 307, lines 25-28). Hans Dahlke places Caesar in a row with the “Brecht characters” Mackie Messer and Arturo Ui and proves the thematic connection between the Caesar novel and the Threepenny Opera . According to Dahlke, the representation of the Caesar figure describes an “exemplary gangsterism” in Brecht. The depiction of Caesar as a “criminal figure” (inter alia p. 342, lines 4–5) necessarily results in the complexity of the Caesar figure. The "gangsterism" of Caesar is connected with his cunning, which is reinforced by the fact that Rarus does not always see through the plans of the politician and the whole sophistication of Caesar's political agitation, which is associated with demagogy and financial calculation, only becomes apparent to the reader late.

City and Senate

The power struggle between the city and the Senate, which is primarily based on economic conflicts of interest, is a central theme of the Brechtian Caesar novel. The so-called “City” is made up of the rich bankers and merchants of Rome and is characterized as “ democratic ”. The “City” represents a role within the novel that illustrates the inability of the rich craft class to intervene against the threat to the republic themselves: Here indecision alternates with greed for profit and cowardice. The city is more aware of the danger posed by Catiline than, for example, the Roman people, but turns out to be incapable of acting in the decisive situations. The lack of leadership within the city ultimately makes them lose the power struggle with the Senate in their internal fragmentation (as far as it can be inferred from the part of the novel executed by Brecht).

The economic and political rival of the city is personified in the large landowners, who have divided political power among three hundred patrician families since the beginning of the republic, primarily in the form of magistrates and seats in the Senate. Although the Senate is part of a (seemingly) democratic republic, it is only interested in maintaining its own power that comes with maintaining the republic. The suppression and destruction of Catiline by the Senate is a product of these overriding economic and power-political interests. The Senate, however, is just as unaware of the threat to the republic and its own position of power as the population. For Brecht, then, characterizing the Senate offers the possibility of depicting the actual fragile structure of a republic that is only kept alive more or less from one day to the next without the majority of the population and the rulers being aware of it seems how near the "demise" of the republican system is imminent.

Other people

In the main plot of the novel, several other historical figures are described, such as Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus , Marcus Licinius Crassus , Cicero and Catiline . All these figures have in common that they fail in their own way in the political process and become objects of the power struggle within the republic. In doing so, Brecht sometimes stylizes them as mere instruments of power by Caesar, the Senate or the City. Pompey appears from the outset as unpopular and, above all, undecided and, as with Caesar, the motivations for his political actions are always financial in nature. However, Pompey is not as skillful as Caesar, which is why he ultimately has to fail politically. According to Brecht's concept, Pompey is ultimately only a pioneer for Caesar; he finally begins the ruin of Rome and Italy with the war in Asia Minor , Caesar completes it with the Gallic War (p. 352, lines 6-10).

The Crassus mentioned in Rarus' records represents the historical Marcus Licinius Crassus , who was known among his contemporaries for great wealth and who participated in the first triumvirate . Rarus describes Crassus primarily as a partner and financier of Caesar. Crassus almost stereotypically represents the character of the rich property owner and businessman, who sweats with heat and baroque corpulence, shakes his head free of humanity and understanding at the complaints of the poor and who pushes his own intellect to its limits when trying to find new and fast methods of To imagine accumulating money. Similar to Rarus, Crassus also represents a representative of that social group who has no empathy for the needs of lower social classes.

Catiline personifies the dictatorship and the overthrow of the republican order. Right at the beginning of Rarus' notes, Catiline appears as a man of the people. However, he is neither the popular he claims to be, nor does he, like Caesar, understand how to use skilful calculations not only to take advantage of the popular unrest, but also and above all of the differences between the city and the senate. In contrast to Caesar, Catiline plans his project in a less pragmatic and forward-looking manner, which is why his efforts to overthrow ultimately fail. The fact that Catiline fails, but that the danger he posed is misjudged on many sides after his death, illustrates the uncertain position of the republic. The awareness of this uncertainty is apparently only present in Cicero, who constantly and sometimes hysterically warns of Catiline. They largely rely on the consul, the people vote democratically, and after the fall of Catiline, the republic is believed to be safe. At this point in time, there was still no talk of a Caesar dictatorship.

In Rarus' notes, the consul Cicero appears to the Roman people as the incarnation of the republic and democracy : he is seen as the opposite pole to Catiline, convinced that there can be no dictatorship, “neither from the right nor from the left” for as long Cicero's power in Rome remains undiminished (p. 213, lines 25-29). Cicero's action against Catiline reinforces his characterization as a politician who strives above all else to prevent a possible fall of the republic through the activities of Catiline. On the one hand, Cicero is the “protector” of the republican-democratic order of Rome; inviolable and determined, he cares for the well-being of the republic. On the other hand, however, the “true” character of Cicero is shown in Rarus' notes. He may indeed defend the republic; The fact that his nervous “actionism” against Catiline in Brecht's portrayal only appears to be an outgrowth of his cowardice and thus presumably political fear of failure is ultimately ridiculed by Cicero's character. Cicero succeeds in preventing the overthrow of Catiline with great effort; Caesar, however, who according to his notes had conceived as the actual ruin of the Republic of Rome, cleverly escaped possible prosecution, which in the long term failed to save the Republic.

The language of the novel

The overall style of the novel is tied to the situation. First of all, the choice of words differs depending on what is happening and the character in the novel. The narrator's language is very verbose and precise. His reports often contain descriptions of the landscape, particularly of Spicer's estates. The vocabulary used by the narrator is largely free of colloquial expressions and also characterized by numerous termini technici that make the young lawyer appear educated (p. 191, lines 35-40).

Rarus' language, on the other hand, is characterized by some colloquial expressions and otherwise differs from the level of the first-person narrator: Paratax alternates with hypotactic sentence constructions (often strings), which are characterized by technical terms , but which are limited to the economic area. However, the sentence structure in the diary entries for hypotactic sentences is kept relatively simple insofar as Rarus always introduces these sentences directly and often without conjunctions with the subject of the main sentence. (P. 339, lines 12-16). The fact that the foreign words used by Rarus are mainly limited to the economic area underlines his characterization as Caesar's secretary, who is familiar with the financial undertakings of the later dictator, but beyond that shows no understanding of the background to those transactions.

Typical of Rarus' articulation are the designations of leading politicians and business people according to their character: Crassus, for example, is often referred to as the “sponge” (p. 209, line 11), the former consul Lentulus is referred to as the “calf” (P. 239, lines 25-33). In addition, Rarus also attaches particular importance to the description of both the external appearance of individual people and their habits and private relationships. For the novel, the resulting subjectivity of the presentation is decisive: On the one hand, the lively narrative style enables the reader to take part in the events and thus increases the credibility of the diary entries. In addition, Rarus 'diary character causes a particular shamelessness of the portrayal, which in turn is ultimately beneficial to Rarus' credibility.

Overall, the novel is ultimately shaped by general terms from modern language such as “ Trust ”, “City”, “Democratic” or “Sturmrotten”. The function of these anachronisms turns out to be not entirely clear. Brecht did not want to write an analogy to the developments of the Weimar Republic, but the novel contains conscious or unconscious allusions to contemporary history (p. 515). Since the unmasking of the Caesar legend and thus of the image of the dictator in general (p. 171, lines 26-28) is linked to the claim to explain contemporary events, one is forced, despite the restriction on Brecht's side, to assume a certain analogy; no other explanation for the linguistic anachronisms can be found in the secondary literature.

interpretation

Leitmotifs

The entire novel by Brecht contains several specific leitmotifs, which in their totality are of central importance for the claim to validity of the work. These leitmotifs are based on the one hand in the socialist attitude of Brecht, on the other hand in the basic literary conceptions generally present in his writings; the former is mainly pronounced on the level of content, the latter on the structural-compositional level.

The "rule of monopoly capital"

The rule of monopoly capital represents the central bone of contention in the dispute between the city and the senate. The content of this dispute is the struggle of "two factions of the ruling class over the best method of exploitation" in the east, that is, the new Roman provinces there; the motives of the Senate and the City differ according to their respective economic interests. Since the expulsion of the last Roman king, the Senate has had almost unchallenged power in Rome, so it is in a defensive position in the fight with the city, while the city represents the aggressor of that power. The common people remain excluded from the clashes: Although the city pretends to support the people and want to help them to get their rights, it is still only acting in its own (mainly financial) interest and is ready to betray the people for it. The “ruling classes” in Brecht's conception of the novel are the City and the Senate, both of which can be described as rival groups of the bourgeoisie .

Crime and power

The connection between crime and power becomes clear in the figure of Caesar. Caesar's ambivalence and his opportunism are the central elements of “gangsterism” in The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar . The cunning that Caesar shows here represents the basis of his criminality, which consists in the systematic instrumentalization of the Roman people: Brecht shows how “the ruling class, in its endeavor to exercise power, deals with the most diverse criminal offenses guilty "makes; These crimes consist of betrayal of the people and war against other peoples as well as extortion, murder and high treason . The “exposure of the crime” as a central motif in Brecht's novel is an essential element of the satirical effect of the work. The crime is ultimately a “political enterprise instigated and paid for by high finance”.

Crime and power are ultimately mutually dependent: the crime is carried out by those who hold power, but power is maintained and increased through crime; the crime is carried out by the ruling class on the back of the ruled class.

Money and economy

The economic aspect plays a central role in the Brechtian novel; the characterization of Caesar and the unmasking of his figure takes place mainly through Caesar's "business". At the same time, the steadily advancing economic ruin of Rome forms the basis for Caesar's political rise; Money and economic calculation remain a prerequisite. The economy of the republic appears desolate for several reasons: First of all, the economic success in agriculture is based on a broadly developed slave economy ; those who cannot afford slaves remain limited to small-scale farming in agriculture. The slave economy is at the same time in competition with the poorer craft class in the city, who see their existence endangered by the slaves as cheap labor. The war in Asia Minor is a burden, because the market is being flooded with new slaves by the Senate's strategy of conquest (pp. 185–186).

Due to the population growth and high unemployment, there is a great shortage of grain, which leads to an increase in grain prices and poverty among the people. Another problem lies in the solution of the land question, which is supposed to guarantee a redistribution of land as arable land to the poorer, war-damaged peasants and also veterans; the Senate (as the representative of the large landowners) opposes the demands of the people. The increasing impoverishment and the economic ruin continue in a steadily rising inflation , the effects of which are reflected in the storm on the exchange offices (p. 242, line 33). Finally, stocks fall and the stock market crashes , the ruin of the Roman economy is at its first peak (p. 283, p. 286). Caesar's political ascent is ultimately based on the direct connection between money and economy: Caesar himself always remains part of the “criminal ruling class”, even if his business does not always seem to be successful and his debts increase. The constant ignorance of the Senate and the City in relation to the increasing misery of the Roman lower class and the greed of the ruling classes for profit thus became a central motif in Brecht's novel. The “rule of monopoly capital” (that is, the large landowners in the Senate and the City, see above) in connection with the “exploitation” of the poor population groups can be seen as an analogy to the oppression of the working class under capitalism; For the big landowners, slavery is a means to an end, that is, in addition to a ruthless strategy of conquest in war, a guarantee of the greatest possible profit. Ultimately, Caesar puts himself at the service of the economic greed of the City and Senate, who pay him for it with their “crooked” money.

“Democracy” - rule of the people?

The “democracy” of the Roman Republic is subject to a clear relativity: the real power position of the plebs is generally called into question by the intrigues and the criminal exploitation of the people by the Senate and City . In addition, the distribution of power in the Senate through the “nepotism” of the noble families is also a sign of the “undermining” of democracy, which is reinforced by the Senate's position of power. In contrast, there is obviously no particular appreciation of democracy among the people: the interests of the people consist in work, livelihood, housing and family (p. 232, lines 25-27). The misery of the people appears to be so great that they can buy the (albeit small) power from them. In Brecht's view, the democracy of Rome appears as a hollowed sham democracy that presents itself as a (viable) means to an end.

In connection with the genre of the historical novel of the 1930s, one can speak of the purpose of exposing the "alleged drives of Hitler and their followers and also" the "reactions of the people strata they misled". Ultimately, “democracy” also becomes an instrument of the economic interests of the ruling class; in the struggles between the city and the senate it has "the function of harnessing the little man for the business of a parliamentary group". Brecht hereby exercises an indirect criticism of the (in his opinion) capitalist ("pseudo") democracy of the Weimar Republic , which for him, in addition to the exercise of power under fascism, represented a form of the "dictatorship of the bourgeoisie".

The "other side's perspective"

Brecht's “Perspective of the Other Side”, which plays a central role in The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar , is expressed in a condensed form in his poem “ Questions of a Reading Worker ”.

The “perspective of the other side”, developed by Karl Marx and taken up by Brecht, describes a principle of historical consideration according to which history is understood not as the history of the “great”, that is, the “rulers”, but as the history of the “ruled” becomes. The extent to which this forms another central motif for Brecht's novel can be seen on the one hand in the concentration on the description of the “oppression of the ruled” (people as well as slaves, Spicer's estate, etc.). On the other hand, it is also made clear in the choice of Rarus as the narrator of the framework story: Although Rarus has a prominent position as Caesar's secretary, he is nonetheless in constant contact with the lower classes of the population (through his love affair with Caebio, through Caesar's clientele as well as through his Opinion polls before the consular elections 694). The “perspective of the other side” and the associated historical perspective ultimately prove to be essential for Brecht's claim to validity insofar as they enable the Caesar legend to be unveiled from the perspective of the common people. The latter sees its necessity in breaking away from the bourgeoisie's false, constructed image of history .

The "V-Effect"

Another means of unveiling the Caesar legend is the " alienation effect ", known above all from Brecht's epic theater , through which, according to Hans Dahlke, the figure of Caesar "is exposed to ridicule and the Caesar legend is exposed". This exposure also corresponds to the noticeable development of the first-person narrator of the framework story. At first, the young lawyer is annoyed by Spicer's shameless treatment of Caesar. After reading the first scroll of Rarus, however, he begins to become skeptical of the heroism of the Caesar figure. The development of the narrator can be equated with the development of the reader.

The role of ancient historiography

The role of ancient historiography within the novel can be deduced from the interaction of the “V effect” and the “perspective of the other side”. The Roman historians are mentioned in several places in the novel (p. 169, lines 25-26, p. 172, lines 15-17). The ancient historians had contributed significantly to the glorification of Caesar; their refutation had to represent a central interest for Brecht in order to guarantee the exposure of the Caesar legend and to destroy all contemporary historical references to Caesar's “glorious” dictatorship. In the sense of Brecht's claim to validity, Brecht ultimately intended to “correct” the (in his sense too positive “bourgeois”) ancient historiography; He gave expression to this correction with certain modifications and additions.

Brecht's claim to validity: the Caesar novel as an analogy to contemporary history?

A typical feature of the historical novels of the interwar period consists in the attempt to explain current political events such as the rise of National Socialism and the failure of Weimar democracy. The "correction" of the Caesar image towards the negative is combined with the unveiling of the transfigured view of the dictatorship that is steadily establishing itself in Germany (and also in Italy ); after all, the first-person narrator declares Caesar to be the archetype of the dictator at the beginning of the novel. The plight of the people and the economic "ruin" of the republic ultimately go hand in hand with the rise of the dictatorship.

Starting with the attempt to explain contemporary events, the Caesar novel is based on a representation pattern that generally describes the emergence of a dictatorship from the economic collapse of a state. According to the theory of the class struggle , the latter is caused by the “rule of monopoly capital ” (see above) and the oppression of the working class . Caesar himself forms an element of that process with his “gangsterism”. The subject of the novel is obviously not really just the person of Caesar, but rather the class situation and the economic context.

History of origin

History of the novel

Some time before he actually began working on the Caesar novel in 1938, Brecht was already concerned with the Caesar figure: In a letter from Brecht to Karl Korsch (1937/38), Brecht's plans for a Caesar play in Paris are mentioned. The preoccupation with Shakespeare's Julius Caesar forms the basis for this project, which Brecht probably already thought of before 1929. In 1932 he discussed the plan for a play with Fritz Sternberg that would focus on the "Tragedy of Brutus". This would have consisted in the fact that with the murder of Caesar the dictatorship would not have been eliminated, but "Rome is only exchanging [e] for the murdered great dictator a worse little one". Brecht was interested in a “sociological” modification of the tragedy, which, however, has proven difficult. It might have been difficult to work out a social justification for the rise and fall of the dictator from the dramatic material of Shakespeare . In order to facilitate the actual development of the play, Brecht decided to do certain preliminary work: In addition to the unfinished novel The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar , he also wrote the short story Caesar and his Legionnaire (1942). Since the complete novel would probably have comprised almost eight hundred pages, a play would probably have been correspondingly extensive. Ultimately, the beginnings of Brecht's exploration of the Caesar material in the true sense of the word go back to his school days, when he had his first experiences with Caesar and Sallust in Latin lessons (pp. 509-510). These can be seen as the basis of his intensive preoccupation with the dictator, while the novel's literary beginnings lie in his idea of revising Shakespeare.

The sources and templates of Brecht

A detailed list of all ancient and historical sources used by Brecht can be found in the commentary of the text edition used, pp. 518-522 (this list is based on Brecht's own notes); only the most important are briefly explained below.

Ancient authors

In addition to Caesar himself, whose writings he reviled right at the beginning of the framework plot (p. 167), Suetonius , Plutarch , Cassius Dio and Sallust in particular can be cited as Brecht's sources from the ancient historians . Brecht takes some passages literally from De coniuratione Catilinae by Sallust, for example Rarus' description of his journey to the battlefield of Pistoria . However, for Brecht's feeling, Sallust was missing some essential things in his description, namely the human circumstances, that is, the misery of the battle, whether it was the cold season and the like. In addition, because of certain questions regarding the truthfulness of Sallust, Brecht probably initially avoided an explicit reference to Sallust and then made subsequent additions.

In Cassius Dio, Brecht takes, in addition to smaller details, particularly the description of Caesar's stay in Spain, which Plutarch and Suetonius only take into account in a few sentences.

In Plutarch and Suetonius , Brecht evidently allowed himself larger and more precise borrowings: it is true that Plutarch was only usable to a limited extent; his high artistic standards were often at the expense of the reality content. Nevertheless, Plutarch served precisely because of his extensive depictions of such (secondary) figures as Cicero, Catilina and the like. Ä. next to Suetonius as the central source of Brecht. In the case of Suetonius, the material conception turns out to be of interest to Brecht: According to Dahlke, it is precisely the numerous (sometimes piquant) details that make Sueton's representation valuable in the sense of Brecht's claim to validity; after all, they are precisely what contribute to an increased “perspective from below”. Ultimately, however, the pirate anecdote makes it clear how Brecht, on the one hand, uses the ancient authors, but on the other hand, makes his own modifications and additions in line with the aim of his novel. These changes in the historical material are based, in turn, on Brecht's general literary and creative claim.

Monographs by bourgeois historians

In addition to the historical sources, Brecht also used the monographs in his sense of “bourgeois” historians such as Mommsen and Guglielmo Ferrero to develop the historical basis of the novel: Brecht must have understood Mommsen's remark that the circumstances of the Catilina conspiracy were in the dark as a challenge. It was therefore particularly attractive for Brecht to refute Mommsen's thesis by presenting economic interests as the central background to the conspiracy. It is noteworthy that Mommsen Brecht also serves as the source of his descriptions for the details of the Catilinarian Conspiracy in addition to the ancient authors, on the one hand because Mommsen provides a comprehensive overview of the epochs, and on the other hand because he describes the events of the conspiracy in detail.

Brecht took over essential details with regard to the slave economy as well as some details from Guglielmo Ferrero. The characterizations of Caesar's women are evidently based on Georg Brandes. In addition, Max Weber's Roman Agricultural History served as Brecht's source; Weber's sociological approach evidently attracted Brecht's interest. Brecht used bourgeois history primarily to acquire the necessary historical knowledge and not to evaluate it positively or negatively. In bourgeois historiography (as well as in ancient writers, see above), Brecht found on the one hand an essential material basis and source of inspiration, on the other hand he added his own formative elements and thus ultimately used history as a means to an end in this point as well.

Literary Influences - The Historical Novel in Exile Literature

When designing his work The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar as a historical novel, Brecht took certain borrowings, but also deliberately differentiated it from other historical novels of exile literature . Significant examples include Lion Feuchtwanger's Josephus trilogy , Alfred Döblin's Das Land ohne Tod, and Heinrich Mann's Henri Quatre novels . The common goal is to process comparable historical events and people or counterexamples to the Hitler dictatorship; they are based on a personalistic view of history and a moral-psychological perspective. Brecht took on the moral criticism that could be transferred to the background of the Hitler dictatorship, but turned away from the personalistic historical image of the rest of the exile literature: his focus is ultimately on the class situation and not on Caesar as an individual figure.

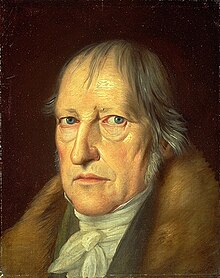

Philosophical and literary theoretical influences: Hegel and Feuchtwanger

The reading of Hegel's lectures on the philosophy of history and the discussion and finally turning away from Feuchtwanger are of central importance in Brecht's novel; For Brecht, Hegel's treatise revealed "the lines of development of Roman history in the transition to empire". Hegel, whose work Brecht himself described as "uncanny" (p. 515), evidently aroused Brecht's interest through his understanding of the great people of world history, whose subjective will is made the object of a "world law". Brecht therefore took over from Hegel the thesis that history takes place as an “interpretation of their [individual individuals] accidental interests in the frame of reference of objective social system constraints”. The contradictory nature of the objective historical process that reveals itself in the Hegelian dialectic therefore served Brecht as an indirect conceptual inspiration for his novel. Furthermore, Brecht Hegel's portrayal of Rome as a “robber state” came in handy, which enabled him to draw the analogy to the “legal” seizure of power by the National Socialists. Hegel's reflections on aesthetics also seem to have influenced Brecht; his marginal notes on his Hegel editions confirm a comprehensive study of Hegel's art-theoretical explanations.

The situation is different with regard to Feuchtwanger: Brecht was in dispute with Feuchtwanger about the “ omnipotence of the historian” in October 1941 (p. 516). This argument forms a point in a long controversy between Brecht and Feuchtwanger about the character of historical poetry. It is true that Brecht and Feuchtwanger apparently shared an interest in Roman history. Feuchtwanger, however, was more concerned with the fate of the Jews and the opposition to German fascism, while Brecht focused on the economic situation: In the Josephus novel Feuchtwanger, for example, Brecht criticized the economic side and the affairs of the ruling class had been neglected, which would have been the central cause of the destruction of Jerusalem . According to Dahlke, Feuchtwanger specialized in "individual psychological screening"; Brecht, on the other hand, hated Feuchtwanger's own statements that “everything psychologizes”, that what counted for him was a “parable situation” and the “authenticity of the word”. The opposing views of Brecht and Feuchtwanger then become clear once again in their respective understanding of the function of the writer: In Feuchtwanger, the writer not only removes the fleetingness of events, but also their ambiguity "by giving the events a real character." . With Feuchtwanger the writer has an absolute claim to truth. Brecht, on the other hand, has created a method of representation that allows as many different uncommented individual judgments as possible to be heard in order to expose the Caesar figure. With this, Brecht guarantees a mixture of subjective, false statements about Caesar and objective, true ones. With this method, Brecht came closer to historical reality than Feuchtwanger.

Reception history

The history of the reception of the Caesar novel is limited to a few isolated essays for the preprint of Book 2, Our Lord C. in Sense and Form . One of the main three reviews of the novel is Ernst Niekisch's work “Heldendämmerung. Comments on Brecht's novel 'The Business of Mr Julius Caesar' ”, which appeared together with the second book in its sense and form (see above). Niekisch tries a general definition of the term “heroism” and describes the novel as “debunking literature”, similar to Sartre's Die Flies . Second, Max von Brück's essay Twice Caesar should be mentioned. This draws a comparison with Thornton Wilder's The Ides of March and presents Brecht's attempt to expose the Caesar figure as a failure. The last essay is Wolfgang Grözinger's review of Bert Brecht between East and West , which refers to the entire special issue of "Sinn und Form" refers and describes the novel as a "hard work". An essential part of the essay is no longer an actual consideration of the Caesar novel, but rather of Niekisch's comments.

Problematically, only the second book and neither the other parts of the book nor Brecht's notes on it were accessible to all authors mentioned (p. 528). Overall, the publication of the second book of novels had no notable effect (p. 528). Brecht, “mainly known as the author of the Threepenny Opera”, has been presented in both sense and form as a playwright , poet and novelist (p. 528). Precisely because of Brecht's high level of awareness, it can be largely ruled out that the low level of reception was due to an equally low level of awareness of the novel fragment. Under certain circumstances, two aspects remain to be mentioned for the low impact of the novel, namely on the one hand that Brecht had just achieved importance as a playwright and that his novel was therefore dismissed more than one attempt. On the other hand, the fragmentary character of the novel can be cited in connection with this, which seems to emphasize the experimental character of the work, but also prevents a complete knowledge of the entire script: after all, an incomplete reading does not allow a comprehensive judgment of the novel.

Directed by Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet , the German-Italian co-production of the film “History Lessons” was made in 1972, which is the only adaptation of the Brechtian novel to date. The film is about a young man from the present who interviews several Roman citizens from ancient times about the rise of Caesar. The film is characterized by artistic and documentary elements; the script is based on Brecht's novel.

criticism

Inaccuracies in content

On closer reading, in particular the framework of The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar , certain major and minor content and historical inaccuracies are revealed. The question arises why the first-person narrator does not seem to have any experience of Caesar's political agitation. In addition, there are obvious contradictions in the determination of the point in time of the framework narrative: The narrator's remark that Caesar had just been dead for twenty years (p. 171, line 15) prompted him to begin with the framework story in 24 BC. To apply. However, the narrator indicates elsewhere that thirty years have passed since Catiline's attempted revolt, from which the year 33 BC emerges. Can be set as the time of the report. This in turn gives rise to another logical problem in the text: In the initial, general remarks by the young lawyer on Caesar's person, he explains that the monarchs had added his (i.e. Caesar's) “illustrious name” to theirs (p. 171, lines 24-25 ). In 33 BC Chr. But is the result of the civil war after Caesar's death still open as Dahlke remarks. Consequently, there is still no monarchy and, above all, not several monarchs who could appropriate the name of Caesar. At this point, the narrator anticipates a future that he may not even know. Even if one assumes that he wrote down his experiences when Augustus was already in power as monarch, he cannot have become so old to experience the general establishment of Caesar's name as the title of prince.

At first glance, two reasons can be found for these content-related and logical inconsistencies: On the one hand, it would be possible that Brecht wanted to revise the novel again and then would have corrected these temporal and historical errors; accordingly one could assign the latter to the fragmentary character of the novel. It is true that Brecht only had the second book of his novel (detached from the framework story) published during his lifetime. However, there is no evidence that Brecht planned to revise the first and third books. Accordingly, the fragmentary character of the novel can only partially explain the logical problems of the plot.

A much more conclusive explanation is given by some texts from Brecht's estate , which reflect his work on the novel. This clearly shows how precisely and carefully Brecht uses historical facts, but also modifies them. At one point he writes that Caesar's land speculation is “nowhere attested”, but Ferrero points out “the shares of the Asian tax companies that Caesar received (after Cicero) for the reduction of the rent”. Brecht was less interested in a historically correct presentation of the events, because the claim to unmask the Caesar legend far exceeds the claim to historical neutrality. The framework itself remains more of a means to an end.

The pirate anecdote as a modification of historical events

The so-called “pirate anecdote” proves to be a particularly good example of Brecht's modification of historical events. In the historical reality of the “pirate anecdote”, Caesar embarks on a trip from Rome to Rhodes after his failure as a lawyer in a trial . On this trip Caesar's ship is captured by pirates and he himself is taken hostage. Caesar sends some of his men out to collect the ransom. Until the ransom arrives, Caesar spends his time with the pirates, composing poems and speeches that he reads to his kidnappers. When they show him no admiration, he scolds them as barbarians and threatens them with a laugh that he will let them untie. After paying the ransom, Caesar is brought ashore. In freedom, Caesar immediately equips ships at his own discretion and pursues the pirates. In a sea battle, he sinks or hijacks their ships and takes the survivors as prisoners. He takes the latter to the propraetor of the province of Asia , so that he punishes the pirates appropriately. The propraetor refrains from doing this and would rather sell the pirates as slaves. Thereupon Caesar had his prisoners crucified without authorization. This passage is in Plutarch and Suetonius described caesar friendly. The resulting “glorification” of Caesar had to be remedied by Brecht according to his validity claim. Brecht adds a few important details to the anecdote: He has Spicer explain that Caesar smuggled a load of slaves on board his ship. This violated the contracts of the slave traders in Asia Minor with the Roman, Greek and Syrian ports. Therefore, according to Spicer, the Asia Minor export trust had seized Caesar's ship and had the cargo confiscated. The ransom was therefore a kind of compensation amount. After Caesar was free again, he attacked the company in Asia Minor in a robbery and had the captured merchants crucified with forged papers (p. 182, lines 30 to 184, line 27). What is remarkable here is that there is no historical evidence for Spicer's statements, so they are Brecht's own invention. It emerges from this that Brecht must ultimately help his claim to expose Caesar as a “criminal figure” by making certain modifications.

The business of Mr. Julius Caesar: a case of historical corruption?

The inaccuracies in the content and the deliberate changes in historical events in favor of the unveiling of the Caesar legend (pirate anecdote) raise the question of how far Brecht's novel can be described as a distortion of history . Of course, The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar is not a factual biography of the ancient politician; one can therefore allow Brecht certain modifications of the historical material. Nevertheless, the work is based on a historical claim. In order to achieve this goal and to ruin Caesar's historical fame, Brecht could not reinvent history, but had to consider certain real facts and incorporate them into his own account of events. The difficulty with which Brecht was confronted in his work on the novel lay in the balancing act between validity claim and credibility: the purpose of the fascism interpretation and the satirical character of the work made efforts not to stray too far from historical reality and difficult letting the novel succumb to unbelievability. In addition, Brecht was concerned with a representation of social relationships from the perspective “from below”. It was important to him to give his portrayal a symbolic character and to let his novel work like a parable on the reader. On the one hand, the novel was conceived as a “counter-speech” against the “historical lies of the Hitler ideologues”, according to Dahlke. On the other hand, however, the work is directed against the "personalistic conceptions of history of the historical novels of exile". These mostly concentrated on the humanization of certain historical persons and described their individual existence. In Brecht, on the other hand, the individual in Caesar is subordinated to the social aspects.

At the same time, Brecht's novel has a certain satirical character, which is associated with a “moral indignation”, according to Dahlke. The latter, in turn, is the “result of a real historical knowledge”. This historical knowledge is based on a central consideration of the "analogue social conditions that passed power to the dictator ". In addition to this, Brecht evidently always ties his “realism” (especially within his works) to the consideration of social circumstances and the class struggle . What problems Brecht had to struggle with in this regard when reading ancient sources and historical literature can be seen from his estate; There he writes how late it first dawned on him “what the action of pompeius, this regulation of the bread supply, must have been about: he had to prostrate the hungry. and i only read these books [!] because i wanted to reveal the business of the ruling classes at the time of the first great dictatorship, so with evil eyes! It is that difficult to decipher the history books ”. The sources that Brecht had at their disposal therefore required certain “interpretations” on the one hand, and on the other hand they did not always turn out to be as detailed as Brecht would have liked. Accordingly, he was evidently compelled to add his own additions (and thus modifications) to the economic history, because, as he lets Spicer remark, "You know that this page interests our historians little" (p. 169, lines 25-26).

On the other hand, Brecht was aware of the problem that his claim to validity inevitably required a historical basis; in addition, he has demonstrably taken great care in the source work. It can therefore be ruled out that Brecht planned to undertake a conscious manipulation of history in the form of historical distortion; the latter would only have put him on a par with the "Hitler ideologues" criticized by him. Brecht considered “the analogy to be a legitimate artistic means”, “provided that the historical peculiarities, the historical uniqueness of the treated case” have been preserved and he (that is, Brecht) was right. In the end, it remains debatable whether Brecht has stylized the Caesar figure as well as the historical events to unbelievability or whether he succeeded in the triad of unveiling, perspective from below and contemporary history.

literature

Text output

- Werner Hecht, Jan Knopf a. a. (Ed.): Bertolt Brecht. Prose 2. Fragments of novels and drafts of novels (= Bertolt Brecht. Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions. Volume 17). Frankfurt am Main 1989.

- Bertolt Brecht: The business of Mr. Julius Caesar. Novel fragment. Berlin-Schöneberg 1957.

Secondary literature

Literature on Brecht's novel "The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar"

- Klaus Baumgärtner: The business of Mr. Julius Caesar , Kindlers Literaturlexikon , dtv, Volume 9, 1974, pp. 3876-3877

- Heinz Brüggemann: Literary technology and social revolution. Experiments on the relationship between art production, Marxism and literary tradition in Bertolt Brecht's theoretical writings. Reinbek 1973.

- Herbert Claas: Bertolt Brecht's political aesthetics from Baal to Caesar. Frankfurt am Main 1977.

- Hans Dahlke: Caesar with Brecht. A comparative consideration. Berlin / Weimar 1968.

- Carsten Jakobi: The epic form as a critique of historiography. Bertolt Brecht's novel The business of Mr. Julius Caesar . In: Carsten Jakobi (Hrsg.): Reception of antiquity in the German-language literature of the 20th century . (= Special issue literature for readers 28/2005, issue 4), pp. 295–311.

- Ulrich Küntzel: Nervus rerum: the business of famous men. Frankfurt a. M. 1991.

- Klaus-Detlef Müller: The function of history in Bertolt Brecht's work. Studies on the relationship between Marxism and aesthetics. Tübingen 1967.

- Peter Witzmann: Ancient tradition in Bertolt Brecht's work. Berlin 1964.

- Olaf Brühl: Not a cold work for a cold world . Berlin 2007.

Literature on Roman history and Caesar as a historical figure

Research literature

- Ernst Baltrusch : Caesar and Pompey. Darmstadt 2004.

- Ursula Blank-Sangmeister: Gaius Julius Caesar. A picture of life. Göttingen 2006.

- Jochen Bleicken : The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Basics and development. 6th edition, unchanged reprint of the 5th, improved edition. Paderborn 1993.

- Luciano Canfora : Caesar. The democratic dictator. A biography. Munich 2001.

- Karl Christ : Caesar. Approaches to a dictator. Munich 1994.

- Werner Dahlheim : Julius Caesar: the honor of the warrior and the need of the state. Paderborn 2005.

- Karl Loewenstein : The governance of Rome. The Hague 1973.

- Martin Jehne : The state of the dictator Caesar . Böhlau, Cologne - Vienna 1987, (Passau historical research 3) ISBN 3-412-06786-5 .

- Wolfgang Will : Julius Caesar. A balance sheet. Stuttgart 1992.

- Maria Wyke: Julius Caesar in Western Culture. Malden, Mass. 2006.

- Horst Zander: Julius Caesar. New critical essays. New York 2005.

Literature used by Brecht (excerpt)

- Georg Brandes : Caius Julius Caesar. Berlin 1924.

- Guglielmo Ferrero : Greatness and Decline of Rome. Stuttgart 1908-1910.

- Theodor Mommsen : Roman history. Karlsruhe 1832-1841.

- Max Weber : The importance of the Roman agricultural history for state and private law. Stuttgart 1891.

Web links

- Bertolt Brecht. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- History lesson (1972) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Olaf Brühl: Not a cold work for a cold world .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Herbert Claas: Bertolt Brecht's political aesthetics from Baal to Caesar. Frankfurt am Main, 1977, p. 117.

- ↑ on the content of the pirate anecdote cf. 7.2 and in the article on Caesar's biography

- ↑ At the time of the Roman Republic, a period was prescribed by law that had to lie between the application for the consulate and the triumphal procession. Caesar had to come to Rome within this period to apply for the consulate.

- ↑ cf. on this: Hans Dahlke: Caesar near Brecht. A comparative consideration. Berlin / Weimar 1968, pp. 111-113.

- ↑ cf. to the "pirate anecdote" point 7.2

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 86-87

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 86

- ↑ cf. on the problem of democracy, point 4.1.4

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 182-184

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 184, cf. Point 2.2.2

- ↑ a b c d Dahlke, p. 109

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 111

- ^ Claas, p. 127

- ↑ cf. Loewenstein, p. 163

- ^ Claas, p. 126

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 101

- ^ Claas, p. 131

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 108

- ^ Claas, p. 179

- ↑ in particular Sallust, Suetonius and Plutarch; see. to the details point 5.1.2

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 106

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 26

- ↑ J. Knopf (Ed.): Brecht Handbook . Stuttgart 1988-1999, vol. 3 p. 282 f

- ↑ quoted by Knopf: Fritz Sternberg: The Poet and the Ratio . Goettingen 1963

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 29

- ↑ published in the "Calendar Stories" (Bertolt Brecht: Calendar Stories. Hamburg 1960.)

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 136

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 138-140

- ↑ Dahlke pp. 128-129

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 131

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 132-133

- ^ Claas, pp. 154-155

- ^ Claas, p. 156

- ↑ Dahlke pp. 95-102

- ↑ Dahlke p. 106

- ^ Claas, p. 157

- ↑ Claas, pp. 157–158

- ^ Claas, p. 158

- ^ Claas, p. 159

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 66

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 67

- ↑ quoted from Dahlke, p. 63.

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 78-79

- ↑ Niekisch, Heldendämmerung. Comments on Bertolt Brecht's novel The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar , Sinn und Form, Volume 1, 1949, pp. 170–180

- ↑ Max von Brück, Twice Caesar , The Present, Volume 5, 1950, pp. 15-17

- ^ W. Grözinger, Bert Brecht between East and West , Hochland, Volume 43, Issue 1, 1950/51, pp. 80–86

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 148

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 148-149

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 149

- ↑ quoted from Claas, p. 232

- ↑ cf. point 7.2

- ↑ Dahlke, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Dahlke p. 103

- ^ Claas, p. 147

- ↑ quoted from Claas, p. 228.

- ↑ Dahlke, p. 106