Agitprop

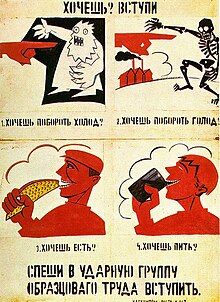

Translation: Do you want? Occurs. 1. Do you want to fight the cold? 2. Do you want to fight hunger? 3. Do you want to eat? 4. Do you want to drink? Hurry up, join the shock brigade (Udarnik) of the model workers.

Agitprop (sometimes also Agiprop ) is an artificial word made up of the words agitation and propaganda and describes a central term in communist political advertising since Lenin . Agitprop was initially the short form of Russian отдел агитации и пропаганды ( otdel agitazii i propagandy , department for agitation and propaganda, established in Soviet Russia in 1920 at all levels of the Bolshevik Party). Agitprop later stood (and partly still stands) for the entirety of the communication of communist politics of Leninist characteristics. The term is positively coined for Leninists .

Furthermore, the term is still used today to denote pejorative, distancing or even colloquially positive advertising campaigns for one's own party.

Definition of Plekhanov

Georgi Plekhanov , the founder of the Marxist movement in Russia , defined the two terms as follows: “The propagandist conveys many ideas to one or more people, while the agitator conveys only one or only a few ideas, but conveys them to a whole Crowd of people. "

Definition of Lenin

Lenin defended Plekhanov's theses against Martynov's attempt at deepening, which defines agitation and propaganda as follows:

“By propaganda we would understand the revolutionary illumination of the entire current social order or its partial phenomena, regardless of whether this takes place in a form that is accessible to the individual or the broad masses. Under agitation in the strict sense of the word (sic!) We would understand: the appeal to the masses for certain concrete actions, the promotion of the immediate revolutionary interference of the proletariat in public life. "

In response to this statement, Lenin wrote:

"That when dealing with the question of unemployment, for example, the propagandist must explain the capitalist nature of crises, point out the cause of their inevitability in modern society, explain the need to transform this society into a socialist one, etc. In a word, he must" many ideas ”, so many that only (relatively) few people will immediately adopt all these ideas in their entirety. The agitator, on the other hand, who speaks about the same question, will pick the most blatant and blatant example known to all his listeners - e. B. the starvation of an unemployed family, the increase in begging, etc. - and will focus all his efforts on conveying an idea to the “mass” on the basis of this well-known fact: the idea of the futility of the contradiction between the increase in wealth and the increase in misery, he will endeavor to arouse discontent and indignation in the crowd at this blatant injustice, while leaving the propagandist to fully explain the origin of this contradiction. The propagandist therefore works mainly through the printed word, the agitator through the spoken word. The same qualities are not required of the propagandist as the agitator. For example, we shall call Kautsky and Lafargue propagandists, Bebel and Guesde agitators. To want to create a third area or a third function of practical activity, namely "the appeal to the masses for certain concrete actions", is the greatest nonsense, because the "appeal" as a single act is either the natural and inevitable complement to both the theoretical Traktats and the propaganda brochure as well as the agitation speech, or it represents a purely executive function. "

Agitprop in the Soviet Union

Since the word agitprop is an action from the Soviet Union , the background to its creation is an important aspect in order to understand its implementation and development. With visual means one resorted to convincing and motivating motives in order to popularize the new regime and to found a cohesive nation. Graphically, pictorially and architecturally, the ideologies were implemented in the form of images and gained great popularity after the end of tsarism .

Early propaganda posters

Up until 1917, tsarism was the current form of rule in Russia ; At that time, Tsar Nicholas II ruled. Due to the hierarchically regulated social system, social inequality arose in Russia, from which the working class society was hardest hit and suffered from major economic problems. The Bolsheviks , the faction of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party, were one of the great critics of the system, which set out to change Russia. Against the tsarist rule and to make its criticism of the regime public, the party illegally worked on leaflets and posters that were issued underground or abroad. Because of the conditions of illegality, the distribution of the posters in densely populated places proved to be very difficult. Nevertheless, in 1901 the RSDAP succeeded in publishing the first oppositional poster "The Pyramid" in Geneva and distributing it among workers.

As a reaction to the social inequality in Russia, " Bloody Sunday " came in 1905 , the first Russian revolution in which the working class society expressed its discontent in the form of an uprising. Despite the calls for help for social and societal improvement, Tsar Nicholas II ignored the fact that Russia was in a state of self-destruction and the people were further oppressed. With the growing urge for change, the prophesied revolution came in Russia in October 1917 , in which the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, took power and ruled Russia from that point on. Since the ruling party of Lenin needed to be popularized, posters were first used in the party's election campaigns in 1917. The potential for agitation and the potential for political use of the poster were recognized and this medium was used more and more frequently to objectify revolutionary change. With tsarism, the censorship in art also disappeared, which is why free poster production was possible and at the same time revolutionary artists and other volunteers called on themselves to support them. The first Soviet posters were therefore primarily political posters related to the traditions of Russian graphic art. Because of the high proportion of illiterate people and those who speak other languages in the Russian population, pictorial representations and little text dominated the posters. Therefore, poster design was based on traditional motifs and allegorical personifications. The content of the political posters had to reach the masses and create change in their minds. In a heroic and satirical way, the poster served as an instrument of agitation and propaganda and was intended to convey the ideologies of the political parties to the population. With this commission, a variety of posters were published, which consciously repeated themselves in content and illustrated the topic of the socialist revolution and the replacement of the autocracy. Since the poster was used not only for political goals but also for economic and social purposes, the images also embodied the mechanization of production and equality for women, among other things. They discussed the enlightenment of the enemy, revolutionary ideology, the need for literacy, the interest in literature and education, health promotion and the new responsibility of women workers. The artist D. Moor (1883-1946) was the inventor of the Soviet political poster design and as a master of political satire he designed illustrations for newspapers and satirical magazines and was therefore one of the most important graphic artists.

Representative of the propaganda posters

With the help of the Russian telegraph agency ROSTA , the striking propaganda campaigns were carried out and made the Bolsheviks very popular. The ROSTA was responsible for the dissemination of current news and designed the posters together with the artists in order to visualize the information. The artist Michail Tscheremnych (1890–1962) designed in 1919 in collaboration with the journalist NK Ivanov the concept of the so-called ROSTA window , which referred to the poster design department in the telegraph agency and was headed by artists, journalists and other intellectual designers. As soon as current reports and news arrived at the telegraph agency, they were visualized by the ROSTA windows with texts and pictures on posters, stenciled and then hung in public space. The posters commented on current issues in politics and society in Russia with pictures and short texts, often in an indirect and allegorical way. The poster production varied in the cities of Russia and required different production techniques. Since most of the printing presses had been destroyed due to the wars, ROSTA in Moscow used stencils to reproduce the posters. Due to the stencil technique, the posters were presented in abstract form and consisted of simple shapes and motifs, often bright colors. The posters were hung in shop windows, kiosks, train stations, marketplaces and other public spaces. The poet and artist Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893–1930) was regarded as the dominant figure in the text and image design of the ROSTA windows, as he was one of the first artists who shaped the art of monumental propaganda and developed new motifs in poster images.

Other forms of propaganda art

In 1918 Lenin called for monumental propaganda to agitate and educate the masses. Therefore, in addition to the striking means, there was also agitation painting and agitation architecture as further forms of propaganda. Since the posters on the vehicles did not promise long-term propaganda opportunities due to the weather conditions, the mobile means of transport, including trains, steamboats and trams, achieved a mass agitation that attracted the population in the most important centers of the Soviet Union (Moscow, Petrograd, Kiev) and above all reached outside of the big cities. The goal was a mass communication that, with the help of the implementation by artists and architects, should inspire the population and educate it politically. Architecture was also part of the monumental propaganda laid down by Lenin, as it provided an effective means of changing the familiar urban environment and of renewing the way of life. In addition, fairs, folk theaters and festivals were organized with agitation, which were dedicated to the joy of the revolution and were of great importance for both political and artistic life. Architectural constructions of a provisional type were produced in large quantities and from inexpensive material, which were presented free-standing or on moving cars in three-dimensional architectural settings during street parades.

Effects on street art

Soviet propaganda art had a huge impact on street art as its function and implementation were heavily used. The dissemination of messages by painting trains, applying stencils and pasting posters in public places is still a current expression of street art today. Strong references to Soviet propaganda can be seen above all in the works of Shepard Fairey . Fairey is a street artist who started a major propaganda campaign around the world with his Obey experiment in 1989. He distributed sticker, poster and stencil images of professional wrestler icon André the Giant in public spaces to find out how a meaningless motif can be made known worldwide. The power and dissemination of the logo in public space confirmed Fairey that the street is of great importance for propaganda and therefore used it in other projects. As a proponent of communism, he refers to leaders like Lenin in his works and copies communist symbols. In his portraits he restricts himself to the black-white-red color scheme, which is typical of the propagandistic character, and avoids the viewer being distracted from the subject of the picture by bright colors, since his primary concern is the content and the effect goes. Fairey was heavily inspired by Soviet propaganda and adopts stylistic features such as reduced coloring, clear forms, typography, image division and heroic depictions of people. The Soviet colors, allegorical symbols, political themes, the nostalgic character and, above all, the propaganda potential of the streets prove the effects of Soviet propaganda art on Shepard Fairey's street art.

Agitprop in the Weimar Republic

In the early days of the Weimar Republic , the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) thought little of art and culture, but described this as a bourgeois "Klimbim" that would only distract from the class struggle . To pursue art without a purpose for its own sake, l'art pour l'art , was frowned upon. When the political situation stabilized in 1923 , the KPD also discovered the long-term value of cultural work based on the Soviet model. In 1925, on the occasion of the 10th party congress, Erwin Piscator was commissioned with the production of the revue “Despite everything”. Piscator, who with the "Proletarian Theater", an agitprop troupe, had wandered through pubs and culture houses for years, proclaimed an uncompromising use of art for the purpose of class struggle. Friedrich Wolf made a similar statement in 1928 in his speech “Art is Weapons” to the Arbeiter-Theaterbund Deutschlands , which was immediately published as a brochure.

At times, however, the KPD leadership went too far; Art, it was said, was "a much too sacred thing to be allowed to give its name to propaganda craftwork". It is interesting that here z. In part, bourgeois standards of value were used.

With the workers 'correspondence movement , workers were introduced to the production of literature, and workers' novels were created in the union of proletarian revolutionary writers . Choirs and revues spread their political ideas in an entertaining way.

The agitprop troops were also important for communist propaganda. These were groups of amateur actors who tried to win supporters with plays, songs and skits in election campaigns or during strikes. Many of these troops emerged from the Volksbühne movement . Organizationally, most of them were connected to the Workers' Theater Association in Germany and the International Revolutionary Theater Association in Moscow. The main goal of the agitprop troops was to spread their ideas, so they felt that the criticism that their performances were bold and that the characters they portray were rather flat, not hit.

Since 1932 at the latest, the agitprop troops had to struggle with performance bans.

Some of the performance songs of these agitprop troops have survived to this day, especially the Rote Wedding of the troupe of the same name, but in the text variant that is widespread today, any allusion to a theater performance has been erased. Other important agitprop troops were the Red Rockets and in Stuttgart the Southwest Spieltrupp founded by Friedrich Wolf .

Agitprop in the GDR

After the popular uprising of June 17, 1953 , the "Agitation and Propaganda" department of the Ministry for State Security , which was established in 1955, was jointly responsible for the propaganda language introduced for the "fascist coup". The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) used intensive political advertising in the GDR . At the different management levels of the SED and the Free German Youth (FDJ) there were functionaries for agitation and propaganda, or AgitProp for short . Many well-known SED officials and members of the GDR government were active in this area of responsibility. Mass organizations such as Young Pioneers , FDJ , FDGB and others were an integral part of the state's propaganda apparatus.

The media highlight of the GDR propaganda was the television program Der Schwarze Kanal . Propaganda methods were an integral part of training for cadres ; B. in the Faculty of Journalism in Leipzig , a training institute of the Central Committee of the SED .

literature

- ^ Ingo Grabowsky: Agitprop in the Soviet Union. The Department of Agitation and Propaganda 1920–1928. Bochum / Freiburg 2004, ISBN 3-89733-101-2 .

- ↑ Peter Kort Zegers (Ed.): Windows on the war. Soviet TASS posters at home and abroad 1941–1945. Chicago 2011.

- ^ Frank fighters: Propaganda. Political images in the 20th century, pictorial essays. Hamburg 1997.

- ↑ a b c Peter Kenez: The birth of the state propaganda: Soviet methods of mass mobilization, 1917-1929. Cambridge 1985.

- ^ A b c d Toby Clark: Art and Propaganda. The political picture in the 20th century. Cologne 1997.

- ↑ a b Hans Schimanski: Guiding principles and methods of communist indoctrination. Party training. Agitation and propaganda in the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany. Bonn 1965.

- ↑ John E. Bowlt: Stalin as Isis and Ra. Socialist realism and the art of design. In: The journal of decorative and propaganda arts, Vol. 24, Design, Culture, Identity (2002) JSTOR 1504182

- ↑ a b David King (Ed.): Russian revolutionary posters. From civil war to socialist realism, from Bolshevism to the end of Stalin. London 2012.

- ^ A b Victoria E. Bonnell: Iconography of power. Soviet political posters under Lenin and Stalin. Berkeley 1997.

Web links

- Erika Funk-Hennigs: The agitprop movement as part of the working-class culture of the Weimar Republic (PDF file; 1.70 MB)

- Agit-Prop-Theater-Collection in the archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/lenin/1902/wastun/kap3b.htm

- ↑ Klaus Waschik, Nina Baburina: Advertise for Utopia. 20th century Russian poster art. edition tertium, Bietigheim-Bissingen 2003.

- ↑ Alex Ward: Power to the people. Early soviet propaganda posters in the Israel museum, Jerusalem. Aldershot 2007.

- ↑ Stephen White: The Bolshevik poster. Yale university press, New Haven 1988.

- ↑ Georg Piltz: Russia is turning red. Satirical posters 1918–1922. Eulenspiegel Verlag, Berlin 1977.

- ^ Maria Lafont: Soviet posters. The Sergo Grigorian collection. Prestel Verlag, Munich and Berlin 2007.

- ↑ Katalin Bakos: Art and Revolution. Russian and Soviet art 1910–1932. Exhibition in the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, March 11th - May 15th, 1988. Vienna 1988.

- ↑ Vladimir Tolstoj: Street art of the revolution. Festivals and celebrations in Russia 1918–1933. Thames and Hudson, London 1990.

- ↑ a b Julia Reinecke: Street Art. A subculture between art and commerce. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2007.

- ↑ Friedrich Wolf: Art is a weapon! A statement. Verlag Arbeitertheaterbund Deutschlands e. V., Berlin 1928.

- ^ Erwin Piscator: Zeittheater "Das Politische Theater" and other writings from 1915 to 1966. Hamburg 1986, p. 43.

- ↑ Michael Kienzle, Dirk Mende: Friedrich Wolf. The years in Stuttgart 1927–1933. An example (= Stuttgart in the Third Reich, exhibition series of the contemporary history project. Volume 3). Stuttgart 1983.

- ↑ Karin Hartewig: Returned: the history of the Jewish communists in the GDR. P. 396.

- ^ Monika Gibas : Propaganda in the GDR. Erfurt 2000.

- ↑ Gerald Diesener, Rainer Gries (Ed.): Propaganda in Germany. On the history of political mass influence in the 20th century. Darmstadt 1996.

- ↑ Günther Heydemann: Historical image and historical propaganda in the Honecker era. In: Ute Daniel, Wolfram Siemann (ed.): Propaganda. Opinion conflict, seduction and political creation of meaning 1789–1989. Frankfurt am Main 1994, pp. 161-171.

- ↑ Brigitte Klump: The Red Monastery. As pupils in the Stasi cadre school. Ullstein Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 1993, ISBN 3-548-34990-0 .