Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky ( Russian Владимир Владимирович Маяковский , scientific. Transliteration Vladimir Vladimirovič Maâkovskij * 7. jul. / 19th July 1893 greg. In Bagdadi , Governorate Kutaisi , Russian Empire , now Georgia ; † 14. April 1930 in Moscow ) was a Soviet poet and a leading exponent of the Russian branch of futurism .

Life

Mayakovsky was the third child and the only son of a forester in Baghdadi, Georgia. The father and mother were descended from Cossacks . At a young age, Mayakovsky took part in demonstrations and read political literature in Kutaisi , where he attended high school for four years. After the sudden death of his father from a blood infection in 1906, the family moved to Moscow in July 1906, where Mayakovsky attended grammar school No. 5. The boy developed a passion for Marxist literature there, took part in actions of the Bolsheviks and joined the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Russia . In 1908 he was expelled from grammar school because his mother could no longer afford the school fees. Mayakovsky was arrested three times in 1908/09 because of his revolutionary "insubordination" and escaped more severe punishments such as deportation only because he was a minor. He wrote his first poems in 1909 in Butyrka prison, a notorious transit facility, which, however, were confiscated by the guards.

After his release from prison, Mayakovsky continued to work in the revolutionary movement. He made the decision to devote himself intensively to painting and began studying at the Moscow Art School in 1911. There he met Dawid Burljuk among his classmates , who recognized his talent for poetry. He joined the futuristic Hyläa group (Гилея) around Burljuk and Velimir Khlebnikov and published his first poems Nacht ( Ночо) in December 1912 in the futuristic almanac A Slap in the Face for Public Taste (Пощечина общественному вкусу ) and Tomorrow (Ночьро). Together with Burljuk he was expelled from the art academy in 1914 because of his political activities.

Mayakovsky signed futuristic manifestos with Burlyuk, Khlebnikov and other students that turned against ancient art and classical traditions and worked towards creating a new literature and poetic language.

Mayakowski's poetry became increasingly linguistically aggressive against the existing system. As early as 1913 he wrote the tragedy Vladimir Mayakovsky and in 1914/15 the poem Cloud in Pants (Облако в штанах). His themes are love, revolution, religion and art:

| Your dream The brain is already effeminate, There was |

Мысль Вашу У меня в душе ни одного седого волоса, |

(from the prologue by Wölkchen in Hosen , translation by Alexander Nitzberg )

His relationship with Lilja Brik , the wife of his publisher Ossip Brik , shaped his work as much as war and revolution.

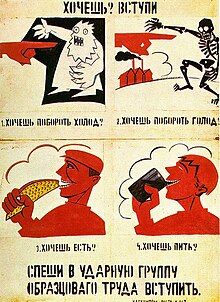

After the beginning of the First World War he was rejected as a volunteer. He then worked from 1915 to 1917 in a Petrograd driving school. When the revolution broke out, he recited poems such as Left March in front of sailors in naval theaters. To sailors (Левый марш (Матросам), 1918). He moved back to Moscow, wrote texts, designed satirical and agitating posters for the Russian news agency ROSTA (so-called Rosta Windows ) and published his first collection of poems, Gesammelte Werke 1909–1919 (Всё сочинённое Владимиром Маяковским.) In 1919 . Its popularity in the young Soviet Union grew; he was a member of the Left Artists' Front (1922–1928) and called his work communist futurism (комфут). The drama Mysterium buffo ( Мистерия-буфф ), in which he wanted to give a “heroic-epic-satirical depiction of our era”, was considered blasphemous by the bourgeois audience because of his Messiah. The proletarian audience had problems with the modern futuristic structure of the piece.

Mayakovsky emphasized in his correspondence as well as in his poetic work how much he adored the revolutionary leader Lenin , for example in the poem Our Youth (1927):

Yes, if I was a negro,

already crooked with age,

I didn't spare my

tired bones

- and learned Russian,

only

because Lenin spoke Russian.

These lines by Mayakovsky were well known both in the Soviet Union and in the GDR . On the occasion of his death, he wrote the poem Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1924). Lenin himself did not appreciate the work of the futurist very much. During a performance at a Moscow university, he advised students to read Alexander Pushkin's works instead . But Lenin's wife Nadezhda Krupskaya and the People's Commissar for Culture Anatoly Lunacharsky were able to convince the head of government that Mayakovsky was addressing young intellectuals and was therefore useful as an agitator.

Several trips abroad - to Latvia , France , Germany , also to the USA - influenced works like How does a democratic republic work? (Как работает республика демократическая? - 1922) and Paris. Conversations with the Eiffel Tower (Париж - Разговорчики с Эйфелевой башней, 1923) and My Discovery of America (Мое открытие Америки, 1925). At the same time, he traveled extensively within the Soviet Union and read his poems in front of a wide variety of audiences; In doing so, he not only experienced understanding and recognition.

In 1922/23 the Brik couple went on a trip to Germany with Mayakovsky, they spent several weeks in Berlin and visited Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus in Weimar . Five more trips to Berlin followed, during which Mayakovsky always stayed at the “Kurfürstenhotel” on Kurfürstenstrasse and went shopping in the Kaufhaus des Westens . According to reports from contemporary witnesses, Lilja Brik, on behalf of the GPU secret police , had to ensure that Mayakovsky stayed away from writers from Russian emigration and the Russian exile press that appeared in Berlin. Mayakovsky himself was on friendly terms with the GPU officer Yakov Agranov , who was responsible for overseeing the writers.

The alleged love triangle between Lilja Brik, her husband Ossip Brik and Mayakowski has been the subject of much speculation. Lilja Brik herself noted in her notes that she had not had any intimate relationships with her husband Ossip Brik for more than a year when her relationship with Mayakovsky began. In the last years of her life she confessed time and again that she only loved Mayakovsky. From her own notes, however, according to the biography written by her last husband, Vasily Katanjan, it is clear that she ended her sexual relationship with Mayakovsky in 1925 after he confessed to falling in love with an American while traveling to the USA. Katanjan, referring to his conversations with her, reported that her relationship with Mayakovsky had been one-sided: he loved her, but she did not reciprocate this feeling, but was happy to accompany him on trips abroad.

On his lecture tour to the USA in 1925 Mayakovsky met the US citizen Elli Jones; He did not see his daughter, who emerged from this brief relationship, until 1929 in southern France. On his travels to France, Elsa Triolet , the sister of Lilja Briks and wife of the communist writer Louis Aragon , had on behalf of the GPU to see to it that he returned to the Soviet Union. In the late 1920s his love was Tatjana Jakowlewa , whom he a. a. Letter to Tatiana Jakowleva (Письмо Татьяне Яковлевой, 1928) dedicated.

His activism as a propaganda agitator found little support, sometimes disapproval , from contemporaries and close friends such as Boris Pasternak (who was still enthusiastic about him in 1913). Towards the end of the twenties, Mayakovsky also criticized developments in Soviet society, especially the growing bureaucracy. This is testified by his satirical drama Die Bug (Клоп, 1929).

Illness and disappointment in private life, criticism and pressure from literary officials shaped Mayakovsky's last months. On April 14, 1930, he shot himself in the heart with a pistol. In a letter he left behind it says:

“As the saying goes, the case is closed; the boat of my love smashed in everyday life. I'm even with life. Don't blame anyone for dying and please don't talk. The deceased didn't like that at all. "

The official funeral commission was headed by the managing director of the Soviet state publishers, Artemi Chalatow , who had recently subjected Mayakovsky to censorship .

Mayakovsky family, Kutaisi 1905

Mayakovsky and K. Tschukowskij with their son Boris, Kuokkala , 1915

Works (selection)

- Night, poem ( Ночь, 1912)

- Morning , poem ( Утро, 1912)

- Vladimir Mayakovsky , tragedy ( Владимир Маяковский , 1913)

- Cloud in Pants , Poem ( Облако в штанах , 1915)

- The Spinal Flute , Poem ( Флейта-позвоночник , 1916)

- Man , poem ( Человек , 1918)

- Mysterium buffo , drama ( Мистерия Буфф , 1918/1921)

- Left march. The sailors ( Левый марш (Матросам) , 1918)

- 150,000,000 , poem (1921)

- I love , poem ( Люблю , 1922)

- How does a democratic republic work ( Как работает республика демократическая?, 1922)

- Paris. Conversations with the Eiffel Tower ( Париж (Разговорчики с Эйфелевой башней) , 1923)

- My discovery of America ( Мое открытие Америки , 1925)

- About it , Poem ( Про это , 1923)

- Vladimir Ilyich Lenin , poem ( Владимир Ильич Ленин , 1925)

- How do you make verses? ( Как делать стихи?, 1926)

- Good and Beautiful, Poem ( Хорошо!, 1927)

- Our youth, ( Russian: Нашему юношеству , Našemu junošestvu , 1927)

- Letter to Tatiana Jakowleva, poem ( Письмо Татьяне Яковлевой , 1928)

- Die Bug, Comedy ( Клоп 1929)

- Verses from the Soviet passport , poem (1929)

- The sweat bath , drama ( Баня , 1930)

German-language editions

- Vladimir Mayakovsky: Works in ten volumes . Translated by Hugo Huppert , edited by Leonhard Kossuth. Verlag Volk und Welt, Berlin 1966–1973 (later with Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1980)

- Poetry album 2 , Verlag Neues Leben, Berlin 1967

- Vladimir Mayakovsky: The flying proletarian . Translated by Boris Preckwitz , illustrated by Jakob Hinrichs. Publishing house J. Frank | Berlin, 2014 (German first publication).

Afterlife and reception

After Mayakowski's death, literary officials initially struck his works from the lists of planned new publications and new editions. When Lilja Brik found out about this, she wrote a letter to Stalin asking for the rehabilitation of her former lover. Stalin had the letter forwarded to the leadership of the GPU secret police . In the margin he had previously written: "Mayakovsky is and will remain the most gifted poet of our Soviet age."

In 1940 the place of birth of the poet in Georgia was renamed Mayakovsky (the place was renamed again in 1990).

The Mayakovsky Museum was set up in Mayakovsky's house, in which he had lived from 1913 until his death. It is located directly behind the Lubyanka , the main building of the NKVD and the later KGB, in Lubjanski Proesd 3/6. The interior of the building was completely gutted except for one room in which Mayakovsky lived and which is furnished with a few personal items and rebuilt in a futuristic style. The visitor moves around on ramps between the walls. Are shown u. a. ROSTA windows, newspaper clippings, photographs, stage sets and posters.

Another reference to the poet is Moscow's Mayakovskaya metro station , which reopened in 2005 after extensive renovations. Extensive ceiling mosaics in the north exit are interspersed with quotations from Mayakovsky and show futuristic graphics. Elaborate furnishings made of marble and metal elements also cite Russian futurism architecturally. There is also a Mayakovskaya metro station in Saint Petersburg .

There are also several Mayakovsky theaters . The former East Prussian town of Nemmersdorf was renamed Mayakovskoye in 1947 . The main outer belt asteroid (2931) Mayakovsky is named after him.

In 1950, a street in the villa district of the Berlin district of Pankow was called Majakowskiring . There are streets named after Mayakowski in Chemnitz , Gera , Leipzig , Rostock and Stralsund, among others .

The historian Ulrich Schneider described Mayakovsky as the poet of the October Revolution and praised his linguistic power, (...) his futuristic and constructivist concepts, (...) his ironic-satirical criticism of bureaucracy, complacency and philistinism as well as (...) his historical optimism .

literature

- Wiktor Duwakin : Majakowski Rostafenster , VEB Verlag der Kunst , Dresden, 1967, DNB 456500995

- Ilja Ehrenburg : People - Years - Life (Memoirs), Munich 1962, special edition Munich 1965, part I 1891–1922, pages 364–377, ISBN 3-463-00511-5

- Hugo Huppert : Memories of Mayakovsky . edition suhrkamp. Frankfurt am Main 1966.

- Hugo Huppert: Mayakovsky . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag (rororo). Reinbek 1977.

- Angelo M. Ripellino: Mayakovsky and the Russian avant-garde theater. Cologne 1964.

- Hans-Joachim Schlegel: Mayakovsky's fascination with films. In: Mayakovsky. 20 years of work. Exhibition catalog of the New Society for Fine Arts. Berlin 1978.

- Nyota Thun: I - so big and superfluous. Vladimir Mayakovsky. Life and work. Düsseldorf 2000.

- Thomas Urban : Russian writers in Berlin in the twenties . Nicolai Verlag, Berlin 2003, pp. 166–193

- Mayakovsky in Berlin . In: Das neue Russland No. 5/6 (1927), pp. 68/71.

- Juliette R. Stapanian: Mayakovsky's cubo-futurist vision . Rice University, Houston 1986, ISBN 0-89263-259-3

Web links

- Literature by and about Wladimir Wladimirowitsch Mayakowski in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Wladimir Wladimirowitsch Mayakowski in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Over 230 publications are listed in the RussGUS database (there search - simple search: majakovskij, *)

- The Mayakovsky bug at the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin

- The Mayakovsky Museum in Moscow

- The State Museum of VV Mayakovsky at Google Cultural Institute

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian house. Chapter 3 - From love to hate and back

- ↑ Mayakovsky Theater Thaw 1979 , Der Spiegel , May 2, 1962, p. 82.

- ↑ Biografija VV Majakovskogo 1920 ( Memento from December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Website of the Mayakovsky Museum, Moscow, accessed on December 1, 2015.

- ^ Thomas Urban: Russian writers in Berlin in the twenties. Berlin 2003, pp. 171-174.

- ↑ Arkady Vaksberg : Požar serca. Kogo ljubila Lili Brik. Moscow 2010, pp. 166, 209.

- ↑ Lilja Brik: “Write verses for me”. Memories of Mayakovsky and letters. Berlin 1991, p. 9.

- ↑ Arkady Vaksberg: Požar serca. Kogo ljubila Lili Brik. Moscow 2010, pp. 41, 117.

- ↑ Vasilij Katanjan: Lilja Brik. Žizn '. Moscow 2002, pp. 61, 72-73.

- ↑ Arkady Vaksberg / Rene Gerra: Sem 'dnej v marte. Besedy ob emigracii. St.Peterburg 2010, p. 176.

- ↑ cf. Nyota Thun: “I - so big and superfluous.” Vladimir Mayakovsky. Life and work. Düsseldorf 2000, pp. 297-312.

- ↑ quoted from: Benedikt Sarnow: Stalin i pisateli. Kniga 1-aja. Moscow 2009, p. 180.

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel : Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition. Ed .: Lutz D. Schmadel. 5th edition. Springer Verlag , Berlin , Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7 , pp. 186 (English, 992 pp., Link.springer.com [ONLINE; accessed on September 23, 2019] Original title: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . First edition: Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg 1992): “1969 UC. Discovered 1969 Oct. 16 by LI Chernykh at Nauchnyj. "

- ↑ Ulrich Schneider: Poet of the Revolution In: Junge Welt , April 14, 2020, p. 12 ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mayakovsky, Vladimir Vladimirovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Маяковский, Владимир Владимирович; Mayakovskij, Vladimir Vladimirovič |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian poet, representative of Russian futurism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 19, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Baghdadi , Kutaisi Governorate, Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 14, 1930 |

| Place of death | Moscow |