Dadaism

Dadaism or Dada was an artistic and literary movement that in 1916 by Hugo Ball , Emmy Hennings , Tristan Tzara , Richard Huelsenbeck , Marcel Janco and Hans Arp in Zurich was founded and "conventional" by rejecting art and art forms - often parodies were - and bourgeois ideals. The Dada gave considerable impetus to art from modern times to contemporary art .

In essence, it was a revolt against art on the part of the artists themselves, who rejected the society of their time and its value system. Traditional art forms have therefore been used in a satirical and exaggerated manner.

expression

The actors of this movement chose the consciously banal-sounding name Dada for their revolt . Dadaism is the term commonly used today for this art movement.

The term Dada (ism) in the sense of the artist stands for total doubt about everything, absolute individualism and the destruction of established ideals and norms . The artistic processes determined by discipline and social morality were replaced by simple, arbitrary, mostly randomly controlled actions in pictures and words. The Dadaists insisted that Dada (ism) is indefinable. When Dadaism began to consolidate, the Dadaists called for this order to be destroyed again, since that was what they wanted to destroy. That made Dadaism what it wanted to be again: total anti-art that was unclassifiable. Comparisons with futurism or cubism were rejected.

Origin of the term and beginnings

Various mutually exclusive theories are circulating about the origin of the term.

George Grosz wrote in his autobiography that the writer Hugo Ball stabbed a German-French dictionary with a penknife in the company of a few artists from various disciplines and met the word dada (French children's language for “ hobby horse ”). After that he is said to have named Dadaism. This is similar to the variant that Hugo Ball and Richard Huelsenbeck looked in a German-French dictionary for a name for the then Swiss singer of Cabaret Voltaire "Madame le Roi" and came across the word "dada".

Marcel Janco, however, himself a Dadaist, explained in an interview that the story with the knife was invented after the fact and that it is a beautiful fairy tale because it sounds better than the less poetic truth. He thought it more likely that a well-known shampoo called “DADA”, which was available in Zurich at the time, inspired the group of artists to name it.

According to another explanation, the term is derived from a publication by the French anarchist Alphonse Gallais. In 1903 he published a book under the pseudonym A. S. Lagail entitled "Les paradis charnels, ou le divin bréviaire des amants, art de jouir purement des 136 extases de la volupté" (Eng. The paradise of the flesh or The divine love brevier. Art to enjoy lust in 136 raptures ). A number of positions are described in Chapter 15, all of which are called “à dada” there. Here, too, the connection to a hobby horse that can be ridden is obvious.

Dadaism questioned all previous art by turning its abstraction and beauty into pure collections of nonsense through satirical exaggeration , as in meaningless sound poems . Hugo Ball was the inventor of the sound poem. The interplay of wording and meaning is broken up and the words are broken down into individual phonetic syllables. The language is emptied of its meaning and the sounds are put together to form rhythmic sound images. The intention is to forego a language that the Dadaists believe is abused and perverted in the present. With the so-called simultaneous poems (sound poems are spoken at the same time by different people at the same time) the Dadaists wanted to draw attention to the deafening background noise of the modern world (in the trenches, in the big city ...) and to the entanglement of people in mechanical processes. In fact, it is often difficult and also pointless to distinguish the “real” works of art of that time from the deliberately more or less senseless “anti-art works” of Dadaism. The boundaries between traditional art and trivial culture were crossed.

During the First World War , Dadaism spread across Europe. Everywhere protested artist targeted provocations and supposed Un logic against the war and the authoritarian civil and artistry. Against nationalism and enthusiasm for war, they took positions of pacifism and sarcastically questioned the values that had previously become absurd.

DADA in Zurich and the Cabaret Voltaire

Originated in Zurich

The background to the development of Dadaism is the situation in Switzerland during the First World War . In all the countries that took part in the war, young artists were excluded from exchanges with their foreign colleagues and friends due to the closure of the borders, and they were drafted into military service. Opponents of the war from different countries gathered in neutral Switzerland, which became the only place of international exchange.

On February 5, 1916, Hugo Ball and his girlfriend Emmy Hennings founded the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich at Spiegelgasse 1, not far from Lenin's exile apartment . At first he performed with her - almost every evening - simple but also eccentric programs. She sang chansons and he accompanied her on the piano. Emmy Hennings also recited poems - among others. his own and those of Hugo Ball. After a few weeks Ball met the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara , who also lived in Zurich. The two sympathized with each other because both had an unusual sense of spirit and anti-spirit. They complemented each other very well because Hugo Ball was rather calm and thoughtful, while Tristan Tzara was an incredibly lively, never calm person. So it was made for Hugo Ball's Cabaret Voltaire. When Tzara then also recited his poems, he often interrupted them himself by screaming or sobbing. The lectures at Cabaret Voltaire were now increasingly supplemented by drumming, beating and the use of misappropriated objects, such as empty boxes. At first the audience reacted very surprised, even intimidated.

During the month of February 1916, Hans Arp and Richard Huelsenbeck joined the DADA activities. They began to make paper and woodcuts , which, like the performances in Cabaret Voltaire, had an anti-art character. Last but not least, Marcel Janco joined the group. He was a Jewish Romanian like Tristan Tzara. Both of them often affirmed in their streams of speech with “there, there”, which translates as “yes, yes”. That could also have been the decisive point for Hugo Ball to call this art “Dada”. Tzara, Huelsenbeck and Janco performed the first simultaneous poem in March 1916 . Sophie Taeuber performed several times as an expressive dancer in the context of DADA Zurich, sometimes as part of a Laban dance group. Two solo appearances in DADA events are documented, one of which was at the opening of the DADA gallery founded by Emmy Hennings on March 29, 1917. She danced to verses by Ball and in a shamanic mask by Marcel Janco.

Tristan Tzara published Dada magazine in 1916 . In the Dadaist circle it was welcome for a poet of his rank to take on this task. With the magazine Tzara tried to get in touch with poets from other countries. Since he was an excellent polemicist for his time , he was of course made for manifestos and similar pronouncements that had the task of "Dadaization". He distinguished Dada from Futurism , which has a program that his works seek to fulfill, while in Dadaism there is no program that can be fulfilled and whose program it is not to have one.

Hugo Ball came across the idea of a “ total work of art ” through Wassily Kandinsky , which brings together many of the human forms of expression, and he initiated several Dada events based on this idea. In addition to the aforementioned, others took part in these: Sophie Taeuber as an expressive dancer (for the first time as a solo dancer at the opening of the DADA gallery in 1917), Suzanne Perrottet as a pianist and the writer Friedrich Glauser . Cabaret Voltaire had to be closed due to complaints from citizens and neighbors. Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara opened a gallery on Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich, which they called “Dada”. They invited well-known painters and sculptors to exhibit with them, including Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Giorgio de Chirico . Every now and then there were quarrels between the visitors, the poets and the artists. Attempts were made to force the “Dadaist” out of the gallery, and some of the artists were jealous of each other. On the other hand, it was mostly too “radical” for the visitors. This attitude worried Hugo Ball and was also the reason for his later withdrawal from Dadaism.

Picture gallery: Performances in Cabaret Voltaire

Marcel Słodki's poster : February 5, 1916

The sound poem

On July 14, 1916, a new form of Dadaism appeared for the first time: the sound poem . It became one of the most important creative fields of the Dadaists. Hugo Ball hosted a Dada evening in a pub. He only reported to Tristan Tzara about his plan to recite phonetic poems as a "magical bishop" in a very special costume:

“I had constructed a costume for it. My legs stood in a round column of shiny blue cardboard that came up to my waist, so that until then I looked like an obelisk. Over it I wore a huge coat collar, which was covered with scarlet fever on the inside and gold on the outside, held together at the neck in such a way that I could move it like wings by raising and lowering my elbows. In addition a cylinder-like, high, white and blue striped shaman hat. "

He had to be carried into the hall in this bulky appearance because he was almost immobile. Hugo Ball first performed these sound poems on June 23, 1916 in Cabaret Voltaire. He himself referred to them in his diary, which first appeared in 1927, as "verses without words". Which verses Ball brought to lecture that evening, his notes leave open; phonetic poems such as Gadji beri bimba (1916) or KARAWANE (1917) are dated . Ball went on to explain the sound poems as follows: “With these sound poems we wanted to forego a language that has been devastated and made impossible by journalism . We have to retreat into the deepest alchemy of the word and even leave the alchemy of the word in order to preserve poetry its most sacred domain. ”When he recited his sound poems, the audience literally exploded into emotional excesses of amazement, amazement, laughter and of disbelief.

After his success, Hugo Ball went to Bern to write for the Free Newspaper , whereby the Dadaist leadership in Zurich passed to Tristan Tzara. A big Dada evening was held, on which many artists performed and recited poems by up to 20 people at the same time, which was repeatedly accompanied by laughter, chants and heckling. Furthermore, the audience was insulted in every imaginable degree. It should be provoked, as never before, in order to push against the "never-existent limits" of Dadaism. The audience, however, responded in part by, for example, chasing Walter Serner off the stage from the building and destroying his props.

Hans Arp once described very clearly how it went when they carried out their program: “Tzara lets his bottom bounce like the belly of an oriental dancer, Janco plays on an invisible violin and bows down to the ground. Mrs. Hennings with a Madonna face tries to do the balancing act. Huelsenbeck incessantly beats the kettle drum while Ball, as white as a chalk like a dignified ghost, accompanies him on the piano. - We were given the honorary title of nihilists ”.

DADA in New York

Dada in New York is considered a short-lived phenomenon in American art history and, due to its “European roots”, was never accepted as an independent American art movement. DADA in New York also started out from European artists who had fled the First World War.

The entire development of DADA in New York was just as focused on "ANTI-Art" as DADA Zurich. The photographer Alfred Stieglitz initially questioned the art of photography as a pure representation: “Photography not only needs to be the reproduction of a real world, it can and should rather contribute to the creation of a new world.” With his magazine Camera Work and his gallery 291 a forum for innovative artists and brought the European avant-garde to New York in numerous exhibitions , but later distanced himself from the Europeans and preferred to turn to local patriotic topics.

A key figure in Stieglitz's circle was the Parisian artist and dandy Francis Picabia , who fled to New York with Marcel Duchamp under the auspices of the First World War and thus became one of the few European participants in the sensational New York Armory Show in 1913. Picabia, who did not feel obliged to any artistic dogma and, like Duchamp, did not regard himself as a Dadaist, provided the theoretical approach for his "anarchic-cubo-realist" iconography and his thoughts on the "exaggeration of the machine" and the creeping industrialization of art the necessary startling liberation of the rigid American art world , still saturated with historicism . From 1917 to 1924 Picabia published the Dada periodical 391 in various cities, including New York.

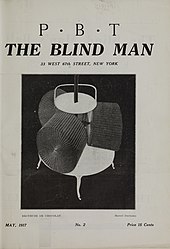

Marcel Duchamp radically continued this train of thought in painting with a playful synthesis of analytical cubism and futuristic dynamics, and expected an entirely new form of art to be presented to the public, more familiar with traditional perspectives. The presentation of his painting Nude, Descending Stairs No. 2 from 1912 was a provocative sensation on the Armory Show and triggered a shock among critics, artists and the general public with its novel “dehumanizing” representation of an “organic apparatus”. The press spoke with euphemistic ignorance of “light as a moving factor in painting”. Subsequently, Duchamp took the experiment with “ANTI-Art”, with machine art, respectively the art made by the machine and the question of what still distinguishes art in his so-called “ ready-mades ” and delivered one Absolute innovation for sculptural representation: He gave objects that he selected to the status of a work of art by declaring that it was a work of art, not because the artist created it, but because the artist "found" it. This is how, for example, the “Fontäne” ( Fountain , 1917) came about , whereby he only bought a urinal from a plumbing store, laid it horizontally “on his back” and signed it with “R.Mutt”. He described these works self-ironically as "nothing". They should symbolize the nothing in which we walk, i.e. the world and life. With his iconoclastic thinking and acting, Marcel Duchamp became, willy-nilly, the Dadaist par excellence, although at the latest since his rejection by the Parisian Cubists in 1912 he had denied belonging to certain groups of artists. In 1917 Duchamp founded the Dadaist publication The Blind Man with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood , which appeared in two editions in April and May of that year. A year later Duchamp finally painted his last painting on canvas: With the programmatic and enigmatic title Tu m ' , Tu m'embetes or Tu m'emmerdes ( “You bored me” or “You can do me” ) he proclaimed “ his weariness with 'retinal art' ”In the following years he devoted himself to his already designed compositions, which he realized with the large-scale stained glass The newlyweds, undressed by their bachelors (1915-23) until his return to Paris in the early 1920s .

The third important protagonist of the New York Dada and at the same time the only member born in America was Man Ray , who also soon broke away from traditional painting and perfected the form of the photogram with his ironic and humorous object art and what he called rayography set the direction for surrealism . It was also Man Ray who, in a letter to Tzara in June 1921, declared the New York Dada to be "dead" with the words "... Dada cannot live in New York".

American Dadaism ended as quickly as it began: On April 1, 1921, the symposium “What is Dadaism?”, Chaired by Marsden Hartley , took place. Meanwhile, in his essay The Importance of Being Dada , Hartley drew a personal balance; at the same time, Duchamp and Man Ray published the first and only issue of New York Dada magazine with Tristan Tzara's "express authorization" to use the term "Dada"; Duchamp went to Paris as early as May; Man Ray and Marsden Hartley followed in July.

Man Ray later stated that there had never been such a thing as New York Dada because "the idea of scandal and provocation as one of the principles of Dada was completely alien to the American spirit".

DADA in Berlin

In Berlin , Dada took on its most extreme form in the world. DADA was only possible in Berlin shortly before the end of the First World War. There it was George Grosz and John Heartfield who took up Richard Huelsenbeck's representations about DADA in Zurich and joined him because they were guided by the same conviction and the same will. On April 12, 1918 Richard Huelsenbeck proclaimed a Dadaist manifesto at a lecture evening in the Berlin Secession , which he also distributed as a leaflet on the occasion, he railed against Futurism and Cubism and proclaimed Dada. Huelsenbeck, having returned from Zurich, “now looked like a match in Berlin, thrown into a powder keg.” Shortly thereafter, the “Club Dada” was founded, which was no less exclusive than the men's club of high-ranking politicians in Berlin. The movement had now consolidated a little, and only the “real” Dadaists of Berlin were represented in this club. One of the club members was Johannes Baader , who adopted the name “Oberdada”, which he justified through extreme deeds which, like Dada himself, “put the crown” on him. He proclaimed himself President of the Globe. Dada was becoming increasingly extreme now. Attacks were carried out in the Dada magazine and certain political figures were insulted.

In Berlin, DADA also brought out a new technique in the field of fine arts with photo montage . The collage had already been used in Zurich , but only newspaper clippings or the remains of boxes, scraps of fabric and paper were used. In Berlin, for the first time, a realistic photo was processed with others to create a new work of art. Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann were the first to try this out. They adopted the principle of so-called military memorial service sheets. These lithographs or oil prints showed the military and often also Kaiser Wilhelm II in glorified form. In the middle of the sheet a soldier could be seen, on whose head the respective photo portrait was glued. The paradox of this technique entered the work of Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann primarily as the interchanging of the head and the body.

New paths were also taken in the direction of poetry. The phonetic poems that Hugo Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp recited in Zurich were mainly developed by Raoul Hausmann.

A total of twelve matinees were held in Berlin, in which the audience was occasionally referred to as idiots and treated as scraps .

The climax of the Berlin Dada took place in 1920 with the First International Dada Fair . Dadaists of all social classes and political views met there. The theme of this fair was, among other things, the hatred of all authority . The works on display, which were created within Dadaism and consisted of magazines, handouts and posters, among other things, made the plurality of the movement clear.

DADA in Hanover

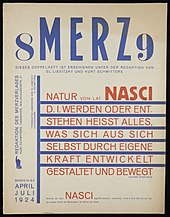

The central figure of DADA in Hanover was Kurt Schwitters . Since he was not accepted into the group of Berlin Dadaists for reasons that were difficult to understand, he renounced the word Dada and designated his own art with the word “ MERZ ”, a syllable that he had cut out of the word “ Commerzbank ” for a collage . As with the Dadaists, his intentions were towards anti-art.

Schwitters and Hannah Höch enjoyed a lifelong friendship from 1920 onwards. Among other things, Höch designed two rooms in his “ MERZbau ” in Hanover.

Kurt Schwitters got on very well with Hans Arp, as both had a similar idea of Dadaism and non-representational art and poetry. This was evident not only in the similarity of the sound poems, but also in the content of their speeches. Kurt Schwitters in particular had a talent for lectures and speeches. Soon after, he also published a magazine called "MERZ".

Kurt Schwitters himself put forward a theory for poetry; a kind of logic of his own, which he called "Schwitters logic". This logic dictated for the poem in general: “Originally, the word is not the material of poetry, but the letter.” According to this, the word is firstly a composition of letters, secondly sound, thirdly designation (meaning) and fourthly the carrier of associations of ideas.

Kurt Schwitters was represented and well versed in all areas of art. He collaged, painted, composed, wrote and composed all kinds of things. However, his idea of art differed from that of Hugo Ball. Kurt Schwitters was not interested in the total work of art, but rather the amalgamation of all art forms into one. The artist is an artist in all fields of art. He lives Dada to the full and focuses on it with all of his senses. Regarding the inclusion of chance , touted by the Dadaists , he noted the following: “There are no coincidences. A door can shut, but that is not a coincidence, it is a conscious experience of the door, the door, the door, the door… ”. He thereby affirms the Dadaist idea that coincidences do not exist in the grotesque and satirical way of Dadaism.

His largest and most extraordinary work of art was the “ Merzbau ”, a room design of the rarest kind. He had created numerous small cavities in a room, all of which were of different sizes, shapes and directions. He himself called them "caves". When the room was full of these caves, he had to break through the ceiling to continue. Each of these caves represented one of his personal thoughts and memories. For example, there was an Arp cave in which he kept the memories of Hans Arp, such as a smoked cigarette and a bottle of urine .

DADA in Cologne

What Kurt Schwitters was to Hanover, the painter and sculptor Max Ernst was to Cologne . Ernst met the painter Johannes Theodor Baargeld and published the Dadaist magazine Der Ventilator with him in 1919 . However, this was soon banned by the British occupation authorities because they had expressed themselves too critical of the church, people and state.

Hans Arp, Max Ernst and Johannes Theodor Baargeld also organized a Dada exhibition here, which was, however, closed by the police because allegedly sexually objectionable things had been seen there, but they prevailed against the judicial authorities. An example of Ernst's Dadaist work is his collage The Hat Makes the Man from 1920, which was included in a 1921 Dada exhibition dedicated to him in the Parisian gallery Au Sans Pareil. Ernst left Cologne a year later and moved to Paris.

DADA in Dresden

The Dresden Dada group was formed in 1919 around the composer Erwin Schulhoff and the painters Kurt Günther , Otto Griebel and Otto Dix . In the summer of 1919 Erwin Schulhoff created the “Five Picturesques for Piano” (WVZ Bek 51), “dedicated to the painter and Dadaist George Grosz with warmth”. One sentence from it, entitled “In futurum”, consisted entirely of pauses. Schulhoff anticipated the silent composition in three movements by John Cage, which was first performed in 1952 .

In 1921 Otto Dix, Otto Griebel and the painter Sergius Winkelmann (1888–1949) published a Dadaist magazine under the title “Moloch”. The group appeared in Dresden with Dadaist actions until 1922 .

DADA in Paris

When Tristan Tzara and the painter Marcel Janco traveled to Paris in 1919 , they found a critical and rebellious mood in the cultural avant-garde there . It was not a completely new confrontation with the ideas of Dada and ANTI art, as in Berlin, but on the one hand the artists were influenced by poets like Guillaume Apollinaire , who had questioned conventional forms of language and poetry a year earlier.

On the other hand, they were also shaped by the experiences of the Zurich Dada, which was only briefly known in Paris. The fact that the Paris-Dada played almost exclusively poets and writers was different here. They limited themselves almost exclusively to writing and reciting poetry. But Paris should also be the location where Dada destroyed himself. The Dadaists became increasingly narrow-minded and fell out among themselves. Everyone went their own way and had their own opinion.

In 1922 the “Congress of Paris” was held, which is considered to be the general dissolution of Dadaism. The problem was that many who attended this congress were ultimately against Dada and the actual Dadaists could not agree among themselves on how to proceed. Another "Dada bomb" was supposed to be set off at this congress, but André Breton , on whom one had relied, instead massively attacked Tristan Tzara, and so here too there was a dispute between former friends. Later, there were sometimes violent arguments at Dada events, where André Breton climbed onto the stage and attacked actors during the performance.

Post-DADA

A few Dadaists later met, such as Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp , Theo van Doesburg and others in Weimar and Strasbourg . Sophie Taeuber-Arp had been commissioned to design the multi-part Aubette pub in Strasbourg: to cope with this major assignment, she brought in her husband Hans Arp and their mutual friend Theo van Doesburg.

Modes of expression

Dada destroyed the separate modes of expression of the arts and brought together various artistic disciplines, some of which were anarchically linked with one another: dance, literature, music, cabaret, recitation and various areas of the visual arts such as image, stage design, graphics , collage, photomontage.

The Dadaists discovered chance as a creative principle. Hans Arp had been working on a drawing for a long time in his studio on Zeltweg. Unsatisfied, he tore the sheet of paper and let the pieces flutter on the floor. When, after a while, he happened to see the tatters again, the arrangement surprised him. It had the expression he had been looking for all along before. Arp also applied the principle to his poetry : “Words, catchphrases, sentences that I chose from daily newspapers and especially from advertisements formed the foundations of my poems in 1917. I often determined words and sentences with my eyes closed ... I called these poems Arpaden. "

Importance and Influence

Dadaism was a very big and radical step in art history in many ways. He brought about many innovations in the technology of the fine arts , just as he had ensured that numerous taboos in the art scene were broken and art is no longer just a reflection of reality, but much more.

The way to surrealism was also prepared. A few Dadaists became surrealists who focused less on the ANTI and more concerned with the sensual world and how best to confuse it. The real world was merged with the dream world and the viewer began to be confronted with insoluble rhetorical riddles. Dadaism finally seemed to die a natural death of disinterest in the 1920s, leaving influential descendants in Concrete Poetry or Lettrism . In addition, modern performance (cf. also Fluxus ) and the idea of the ready-made go back to Dadaism .

Marcel Duchamp's Dadaist idea of the ready-made can often be found in art today. However, it no longer serves to destroy art in general, but rather as an occasion for sensual enjoyment and as a starting point for interpretation that is liberal in terms of content. But this idea in art is omnipresent and is discovered on a stroll through every art museum with contemporary works and with many ready-mades. Repeating a shock, as Marcel Duchamp did with his “fountain” or his “coal shovel”, is no longer possible. That is a thing of the past and even then it was over when you looked at it for the second or third time.

Now, however, what the Dadaists never wanted has happened, namely that they now hang in the museum, next to the pictures by Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee . They really only wanted to destroy what they seem to have become themselves today, namely the stale and established.

The influence on the music (hit " Da da da " by Trio ) is controversial - like everything with Dada. What is at least striking is that the German hits of the 1920s made considerable use of seemingly Dadaistic nonsense texts (for example by the Comedian Harmonists ); even children's songs from this period (such as the famous three Chinese with the double bass ) support the thesis that Dada had become socially acceptable to a certain extent .

Dada can also be understood as an artistic reaction to the tremors of the First World War. The destruction of all valid values and bourgeois norms by the First World War as well as the resulting cultural void was countered by a free, disrespectful art that was supposed to provoke the citizens, for example with public abuse.

Despite the cliché of destruction, Dadaism was able to create a niche for itself and survive to this day. It is cultivated especially by some cabaret artists as a sarcastic criticism of the art world. The most important representative in the post-war period was Ernst Jandl ( vom Vom zum Zum , ottos mops ).

Some current cultural workers are also making use of Dadaist ideas, for example

- the artist trio Studio Braun , they are known for their projects with a pronounced penchant for Dada.

- the band Dada (ante portas) (Dada in front of the doors), which, like the roots of Dada culture, comes from Switzerland

- Jonas Odell, who shot a Dada-style music video for the British band " Franz Ferdinand " ("Take me out")

- the Japanese noise artist Merzbow , who not only named himself after a Dada work of art, but also incorporated various Dada techniques (“found sounds” ...) into his constructions

- Jörg Immendorff and Chris Reinecke in their LIDL action program

- With “Dada in Berlin” the (East) German punk rock band Die Skeptiker released a song on the subject in 1988 ; at the same time symbolizing the attitude of the so-called other bands of the former GDR

- Helge Schneider , whose improvisations, word games and onomatopoeia (“learning, learning, poperning”) arouse Dadaist associations

- the Stuttgart band Freundeskreis , who used many Dadaist style elements in the poetry on their debut album " Quadratur des Kreises ". "ANNA, how was it with Dada", "... les Dada, when I sit on my bed ...", "Comedy is tragedy in mirror writing"

- the Swiss musician duo Yello in their title Planet Dada

- the Swedish DJ duo Dada Life , whose tracks and behavior are very similar to Dadaism

Major Dadaists

- Hans Arp (1886–1966), Germany and Switzerland

- Johannes Theodor Baargeld ("Zentrodada", 1892–1927), Germany

- Johannes Baader (1875–1955), Germany

- Hugo Ball (1886–1927), Switzerland

- Otto Dix (1891–1969), Germany

- Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931), Netherlands

- Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), France and USA

- Max Ernst (1891–1976), Germany, France and the USA

- Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874–1927), Germany and USA

- George Grosz (1893–1959), Germany and USA

- Raoul Hausmann ("Dadasoph", 1886–1971), Germany (Berlin)

- John Heartfield ("Monteurdada", 1891–1968), Germany

- Emmy Hennings (1885–1948), Germany and Switzerland

- Hannah Höch (1889–1978), Germany

- Angelika Hoerle (1899–1923), Germany

- Richard Huelsenbeck (1892–1974), Switzerland and Germany

- Marcel Janco (1895–1984), Switzerland

- Paul van Ostaijen (1896–1928), Belgium

- Francis Picabia (1879–1953), France

- Man Ray (1890–1976), USA, France

- Hans Richter (1888–1976), Germany and USA

- Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948), Germany (Hanover) and England (" Merzkunst ")

- Walter Serner (1889–1942), Italy, France, Switzerland

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943), Germany, Switzerland and France

- Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), Switzerland, France

- Melchior Vischer (1895–1975), Czech Republic, Germany

- Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), USA

Neo-Dada

At the end of the 1950s, neo-Dadaism , which is based on Dadaism, emerged.

Movie

- 1969: Germany Dada , documentary by Helmut Herbst , Cinegrafik, Hamburg, 63 minutes. Edition filmmuseum 108, 2018, ISBN 978-3-95860-108-6 .

- 2011: What is Dada? Films by Heinz Bütler, Alexander Kluge , dctp.tv / NZZ Format 2011, 180 minutes, 2011, ISBN 978-3-89848-394-0 .

- 2016: The Dada Principle , documentary by Marina Rumjanzewa , SRF (editorial staff Sternstunde Kunst ) 2016, 52 minutes.

literature

- Oliver Ruf: Dadaism. In: Gert Ueding (Ed.): Historical dictionary of rhetoric . Volume 10, WBG, Darmstadt 2011, Col. 185-197.

- Hanne Bergius : Dada's laugh. The Berlin Dadaists and their actions . Anabas, Giessen 1993, ISBN 3-87038-141-8 .

- Hanne Bergius: assembly and metamechanics. Dada Berlin - Aesthetics of Polarities (with reconstruction of the First International Dada Fair and Dada Chronology), Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 978-3-78-611525-0 .

- Hanne Bergius: Dada triumphs! Dada Berlin, 1917–1923. Artistry of Polarities. Montages - Metamechanics - Manifestations . Translated by Brigitte Pichon. Vol. V. of the ten editions of Crisis and the Arts: the History of Dada , Stephen Foster (eds.), Thomson / Gale, New Haven, Conn. i.a. 2003, ISBN 978-0-816173-55-6 .

- Richard Huelsenbeck (Ed.): Dada - A literary documentation. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1964, ISBN 3-499-55402-X .

- Richard Huelsenbeck: Dada logic 1913–1972. Edited and commented by Herbert Kapfer . Belleville, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-943157-05-5 .

- Hermann Korte : The Dadaists. 5th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-50536-2 .

- Hans Richter : Dada - art and anti-art. Dada's Contribution to 20th Century Art. M. DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1973, ISBN 3-7701-0261-4 .

- Karl Riha , Jörgen Schäfer (Ed.): Dada total. Manifestos, actions, texts, pictures . Reclam, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-15-059302-6 .

- Peter Schifferli Ed .: That was Dada - Seals and Documents. (= DTV special series. Volume 18). Munich 1963.

- DADA Zurich. Seals, pictures, texts . Arche-Verlag, Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-7160-2249-7 .

- DADA documents of a movement. Art Association for the Rhineland and Westphalia, Düsseldorf 1958.

- Reinhart Meyer et al .: Dada in Zurich and Berlin 1916–1920. Literature between revolution and reaction. Scriptor, Kronberg Ts 1973, ISBN 3-589-00031-7 .

- Raimund Meyer, Judith Hossli, Guido Magnaguagno, Juri Steiner, Hans Bolliger (eds.): Dada global. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-85791-224-3 .

- Gregor Schröer: L'art est mort. Vive DADA! - Avant-garde, anti-art and the iconoclasm tradition . Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89528-484-X .

- Dada. 113 poems . Edited by Karl Riha. Wagenbach, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8031-2477-8 .

- Günther Eisenhuber: Manifestos of Dadaism. Analysis of the program, form and content. (= Aspects of the avant-garde. Volume 8). Weidler, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89693-464-3 .

- Klaus Groh : The New Dadaism in North America. (= Series of scientific texts. Volume 13). Maro Verlag, Augsburg 1979, ISBN 3-87512-113-9 .

- Hubert van den Berg: Avant-garde and anarchism. Dada in Zurich and Berlin. University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8253-0852-9 .

- Raoul Schrott : DADA 15/25. Documentation and chronological overview of Tzara & Co. Verlag DuMont, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-8321-7479-6 .

- Michel Sanouillet: Dada à Paris. Revised new edition. CNRS Éd., Paris 2005.

- engl. Dada in Paris. MIT Press, 2009.

- Manfred Engel : Wild Zurich. Dadaist primitivism and Richard Huelsenbeck's poem "Ebene". In: Jörg Robert, Friederike Felicitas Günther (Hrsg.): Poetik des Wilden. Festschrift for Wolfgang Riedel. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8260-4915-6 , pp. 393-419.

- Willy sales , Marcel Janco, Hans Bolliger (eds.): Dada - monograph of a movement Niggli Verlag , Teufen 1958.

- Ina Boesch: The DaDa. How women shaped Dada. Scheidegger and Spiess, Zurich 2015, ISBN 978-3-85881-453-1 .

- Martin Mittelmeier: DADA. A story of the century. Siedler, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-8275-0070-0 .

Web links

- Ludger Derenthal: Dada, the dead and the survivors of the First World War

- mital-U.ch Dada Situationist

- International Dada Archive The University of Iowa Libraries (images and texts by leading Dadaists)

- Dada online

- Dada opening manifesto by Hugo Ball on Gutenberg.de

- Dada Companion: Chronology and Artists (English)

- Dada Digital Project Kunsthaus Zürich . On the occasion of Dada's 100th birthday, all documents and works were digitized on paper.

Individual references and sources

- ↑ The Diseuse Marietta di Monaco confirmed this variant with minor deviations, but complained about the naming for itself: “One evening Hülsenbeck said she [d. i. 'Madame le Roi'] would not suit us. But Hugo Ball replied: 'We need them for our color!' - 'This is our hobbyhorse!' / And Marietta answered promptly: 'Our DADA.' She had translated Hobby Horse into French, which at first only the Romanians [d. i. Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco] who cheered with the Alsatian [Hans Arp]: 'Now we have a name! - We have a dada! ' - 'We're doing Dada here!' said Tristan Tzara […]. “Marietta di Monaco: I came - I'm going. Travel pictures, memories, portraits . Allitera, Munich 2002, p. 78.

- ↑ Arno Widmann: Dada riddle solved . In: taz , November 26, 1994.

- ↑ Hugo Ball: The Escape from Time . Ed .: Bernhard Echte. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-197-2 , p. 80 .

- ^ Sophie Taeuber-Arp as a dancer and dadaist. A wish from the reception? by Walburga Krupp in: Monte Dada , eds. Mona De Weerdt and Andreas Schwab, Stämpfli Verlag, Bern 2017

- ↑ a b Diary entry by Hugo Ball from: Hugo Ball: Escape from time . Zurich 1992, p. 105.

- ↑ Freiburg Literature Office: Speaking about language - Gadji beri bimba - The sound poem in Dadaism ( Memento from February 15, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), as of March 26, 2008.

- ↑ Reinhard Döhl: Dadaism. University of Stuttgart, archived from the original on February 7, 2009 ; Retrieved March 26, 2008 .

- ^ Francis Picabia - His Art, Life and Times , Princeton University Press, 1979, pp. 71-100.

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp - biography, life and work. In: Calvin Tomkins: A Life Between Eros, Chess and Art. Retrieved February 28, 2009 .

- ^ Alfred Nemeczek : The image of art . DuMont, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-7701-5079-1 , pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Karin Thomas : Until today: Style history of the fine arts in the 20th century. 7., revised. Edition. DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-7701-1939-8 , p. 92f.

- ^ Hermann Korte: The Dadaists . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2007, p. 113.

- ↑ Townsend Ludington: Marsden Hartley: The Biography of an American Artist. Cornell University Press, 1998, p. 157.

- ↑ Quoted from Helmut Schneider: Dada in New York. In: The time . 02/1974.

- ^ Richard Huelsenbeck: Dada logic 1913-1972 . Ed .: Herbert Kapfer. Belleville Verlag, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-943157-05-5 , pp. 529 .

- ↑ Hannah Höch: Overview of life . In: Berlinische Galerie (ed.): Hannah Höch 1889–1978. Your work, your life, your friends . Argon, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-87024-156-X , p. 196 .

- ^ Hans Richter: DADA art and anti-art . DuMont, Cologne 1978, p. 119.

- ↑ Sabine Peinelt: “Dadaist Grand Victory !”? Dresden artist and Dada 1919–1922 . In: Stadtmuseum Dresden (Hrsg.): Dresdner Geschichtsbuch . tape 15 . Altenburg printing house, 2010, p. 195-222 .

- ↑ The Dada Principle. Swiss Radio and Television SRF, February 3, 2016, accessed on February 6, 2017 .