Chanson

Chanson [ ʃɑ̃ˈsɔ̃ ] ( French: song ) describes a song-like musical genre that is rooted in the French culture and is characterized by a singer and instrumental accompaniment. From the 19th century onwards as a clearly contoured, “typically” French variant of international pop culture , the chanson has developed increasingly in the direction of pop, rock and other contemporary styles.

term

The origins of the chanson go back well into the Middle Ages . Two different forms developed early on - a literary, courtly one , derived from medieval troubadors , and a popular one. Because of its long history, its spread beyond the French-speaking area and because of the different styles with which it has blended over time, it is difficult to clearly distinguish it from other musical genres. In particular, the delimitation is not clearly defined:

- to the German-language song or to the German songwriting scene

- to the German hit

- for cabaret or variety songs as part of a program or show

- to Anglo-Saxon folk music or the singer-songwriting common in the Anglo-Saxon region and

- to Anglo-Saxon pop music.

There is broad agreement that modern chanson is primarily a French achievement. Although there is also a diverse chanson tradition in Germany , it was always overshadowed by popular music there. There are some remarkable chanson traditions in the Benelux countries, in Switzerland and in the French-speaking parts of Canada , and there are also significant parallels to the Italian-speaking canzone .

A special feature of the chanson is its concentration on the text message, the requirement to get a message to the point in "three minutes". The division of labor into auteur (text writer), compositeur (music composer) and interprète (interpreter) is characteristic of modern chanson - a threefold structure that corresponds to the singer-songwriter common in Anglo-Saxon. Chanson writers often use poetic imagery and use spoken chants or completely spoken texts in alternation with vocal passages. The texts themselves cover a multitude of topics and moods: from the politically influenced chansons to comical situations to the frequent love songs, chansons report on all situations in life, often with the help of irony and satire . A contemporary witness from the era before the First World War outlined the breadth of the topics with the words: “One sang chansons of all kinds: scandalous, ironic, delicate, naturalistic, realistic, idealistic, cynical, lyrical, nebulous, chauvinistic, republican, reactionary - just one kind not: boring chansons. "

From the 1960s onwards, the genre increasingly adapted to internationally popular musical styles such as rock 'n' roll , funk and new wave . Increasingly, it also opened up to influences from jazz , world music and hip-hop , and since the turn of the millennium also electronic music . Chansons are therefore not characterized by a typical style of music. Formally, a chanson can be a blues , a tango , a march or a rock ballad , incorporate swing and flamenco or be based on the simple waltz-like musette . Since it is difficult to distinguish it from neighboring styles, reviewers often make do by pointing out whether a song is a chanson or not. The main practical criterion is usually the question of whether a song or artist is to be classified in the broader sense of the tradition of chanson. Depending on the context in which one speaks about "the chanson" or a certain chanson epoch, different historical references or musical styles can be meant:

- historical forms of chanson. The older forms, dating back to the Middle Ages, play a major role, especially for the history of songs. They are also interesting as objects of cultural historical and literary studies

- the literarily demanding chanson, which goes in the direction of cabaret - the chanson form that has established itself primarily in German-speaking countries

- the folk song influenced by popular musical forms such as the musette

- the classic French chanson, as it can be found until the 1960s. Characteristic: often (but not only) a small classical line-up or acoustic band with guitar , piano and double bass

- the pop chanson or French pop : French variant of Anglo-American pop music

- Chanson as a generic genre term for all possible musical styles, as long as they contain recognizable song structures. This chanson term is predominant in modern nouvelle chanson .

In the course of its development, the chanson has gone through different forms and forms. The beginnings go back to the Middle Ages. The modern chanson as a French variant of pop culture emerged in the 20th century. Current forms and trends often operate under terms such as Nouvelle Chanson or Nouvelle scène française. Other minor, sub-and special forms are known under the names Chanson à danser (simple folk dance song), Chanson d'amour (love song), Chanson à boire (drinking song), Chanson de marche (marching song), Chanson de travail (work song ) , Chanson engagée (committed, often socially critical song), Chanson noir (chanson with pessimistic content), Chanson populaire ( chanson known and loved in all social classes), Chanson religieuse (religious song) and chant révolutionaire (revolutionary battle song). The chanson réaliste at the beginning of the 20th century, which is based on the tradition of naturalism , and the chanson picturesque, the picturesque chanson that was particularly popular in the post-war period, proved to be the style-forming, formative directions for chanson of the 20th century .

history

Prehistory: Middle Ages to the 19th century

The first demonstrable pre-forms of the chanson already existed in the early Middle Ages. On the one hand war songs from the time of the Franconian Empire , on the other hand folk songs and choral songs , some of which go back to pre-Christian times, have been handed down. Only a few of them have survived. The Roland song belonging to the genre Chanson de geste , the song of war and doom in the fight against the heathen, is considered to be important. Literary scholars and historians therefore date the beginning of a chanson culture in the narrower sense to the High Middle Ages . The first French entertainment songs can be found in the 12th century . An important genre was the form of the courtly art song, which was created around the same time as the Crusades . An important exponent were troubadors, who mostly came from the knighthood and cultivated a special form of the love song known as minnesang . In northern France these singers were called Trouvères .

The second historical predecessor is the popular song. Its origins also go back to the Middle Ages. Its carriers were traveling singers (among them also priests) who performed street songs in marketplaces. Due to their sometimes critical content, their distribution was often restricted by ordinances and laws. A later predecessor are the polyphonic song movements from the Renaissance period . Two poets from the 15th century were considered important sources of inspiration well into the 20th century: François Rabelais and François Villon . The chanson as a text-based song with a simple melody and chordal accompaniment was created around the same time as vaudeville in the 16th century . The practice of chanson and vaudeville singing contributed to community building in absolutist France. In the 18th century, chansons were a natural part of the French opéra-comique .

On the occasion of informal gatherings, the so-called Dînners du Caveau, which spread in the first half of the 18th century, the chanson also became popular among artists, writers and scholars. Socially critical, satirical or poetic songs increasingly determined the repertoire of contemporary pieces. In the era of the French Revolution , mobilization songs increasingly came to the fore as a new type. Well-known examples: the two revolutionary hymns Ça ira and La carmagnole de royalistes . The eight-volume Histoire de France par les chansons documented over 10,000 songs in 1959 - including over 2,000 from the revolutionary era between 1789 and 1795. The further development of the chanson was largely influenced by the activities of the two songwriters Marc-Antoine Désaugiers (1742–1793) and Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780–1857). Although Béranger's opposition stance is judged rather ambiguous in retrospect (for example, after the July Revolution in 1830 , he supported the “citizen king” Louis-Philippe ), in the 19th century he temporarily enjoyed the reputation of a French national poet . Along with the industrialization of France and the political disputes in the course of the 19th century, the repertoire of different mobilization, ideological and memorial songs continued to grow. Many were created in memory of the suppression of the Paris Commune (example: the piece Elle n'est pas morte from 1886 ) or otherwise placed themselves in the tradition of the socialist workers' song .

The classic chanson era: 1890 to 1960

From the 19th century, the French chanson developed internationally as a hit and cabaret song. In contrast to the operatic aria and the operetta hit , it was basically independent of a stage act, was not necessarily sung like an opera and usually had no choir. While the tradition of the literary chanson shifted more and more into the sphere of different clubs and societies, cafés and variety theaters became more and more important as venues - a consequence of the fact that the theaters had meanwhile lost their monopoly on public performances. As amusement establishments for workers and an initially predominantly petty bourgeois and later also bourgeois public, the first cafés chantants emerged on the arteries of Paris in the 1830s, following the goguette. This was followed by the café concerts , located mainly in the north-eastern districts, on Montmartre and in the Latin Quarter , in other words in the districts in which the so-called “classes laborieuses” lived. There should and presumably not only harmless texts were performed, but also socially critical and political songs. The Eldorado, which opened in 1858 and which, with its 2,000 seats, was elevated to the status of the Temple of Chanson, and the Scala, built in 1856, became famous. At the end of the century, the literary and artistic establishments opened in the Paris district of Montmartre , such as Le Chat Noir, founded in 1880 by Rodolphe Salis . Variety theaters such as the Moulin Rouge , the Folies-Bergères and the Olympia were added as additional venues . Together with the first cinemas, they competed with the café concerts and eventually ousted it.

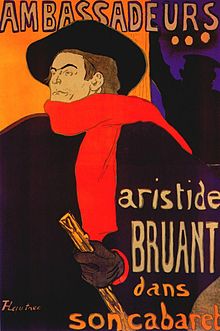

Since the chanson was associated with high explosive power, especially since the revolution of 1789, these amusement establishments were viewed with suspicion. Napoleon I had reintroduced the previously suspended censorship in 1806 and extended it to chanson texts. The success of the café-chantants and café-concerts led to a large number of chansons, which required an increasingly tight censorship system. According to contemporary estimates, 300,000 chansons were produced annually in Paris alone in the 1880s. The forbidden chansons actually included numerous socially critical and anarchist chansons. They criticized social injustice and caricatured the way of life of the bourgeoisie (e.g. Les infects by Leonce Martin or Les Bourgeois by Saint-Gilles) as well as their fear of the assassinations of the anarchist Ravachol (for example the song La frousse, which was written in La Cigale in 1892 should be sung). Other chansons took up the denotations of the ruling class that disparaged workers and reassessed them positively. Normally, these chansons would have strengthened the self-confidence of the workers, such as Le prolétaire by Albert Leroy or Jacques Bonhomme by Léon Bourdon. The censorship system that worked until 1906 tried to prevent this. The café concerts had to submit the lyrics and put up a track list on the evening of the performance so that the officials could check the repertoire. As changes were often made or the wording was changed during the performance, officials were finally sent to the events to compare the wording of the chansons sung with the texts submitted. The first modern chanson singer and pioneer of naturalistic chanson is generally considered to be Aristide Bruant - a friend of the poster painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec . Bruant was very popular as a singer; In Chat Noir he often performed in front of prominent writers and composers such as Alexandre Dumas , Émile Zola and Claude Debussy , who occasionally used to conduct folk choirs with a brass fork in Chat Noir . Yvette Guilbert , a well-known singer and diseuse who appeared in both Chat Noir and the Moulin Rouge, brought the chanson to Germany due to her regular stays in Berlin .

At the turn of the century, a type of chanson strongly influenced by literary realism emerged, the chanson réaliste. His stronghold were the cafes and cabarets in the Paris district of Montmartre, especially the Chat Noir and the Moulin Rouge. Until the First World War, Montmartre was a center for hedonistic, sometimes frivolous, entertainment. The chansons réalistes were heavily influenced by the naturalistic movement in art. Above all, they addressed the world of the socially marginalized - thugs, prostitutes, pimps, orphans and waitresses. Well-known performers of the metropolitan chanson realiste were Eugénie Buffet , Berthe Sylva and Marie Dubas . The recognized stars of the urban chanson réaliste were, besides Aristida Bruant, two other women: Damia and the singer Fréhel , who was quite popular in the 1920s . The Breton singer Théodore Botrel embodied a rather rural song conception, characterized by traditional values . His song La Paimpolaise was one of the most popular chansons at the beginning of the century. One of the most successful chansonniers of the turn of the century was Félix Mayol . The piece Je te veux by Erik Satie (1897), Mon anisette by Andrée Turcy (1925), the anti-war song La butte rouge (1923) and the first recorded by Fréhel La java bleue (1939) also became early classics of the chanson .

The further development of the French chanson was strongly influenced by the emergence of jazz. The small ensembles in particular proved to be chanson-compatible. The outstanding chanson interpreter of the 1930s was Charles Trenet , who was temporarily accompanied by the jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt . Jean Sablon , another much sought-after interpreter of the 1930s , was also heavily inspired by swing and jazz . Other well-known artists were the singer Mistinguett , who was revered as the queen of revue theaters , the singer, dancer and actor Maurice Chevalier and Tino Rossi . The Mistinguett arose from serious competition from the dancer and singer Josephine Baker , who moved to France in 1927, from St. Louis , USA . Édith Piaf , who - like Charles Trenet - celebrated her first successes at the Théâtre de l'ABC in Paris at the end of the 1930s, shaped the further development of the genre . She achieved her breakthrough with chansons by the lyricist Raymond Asso , who also wrote lyrics for other well-known chansonniers such as the Music Hall singer Marie Dubas. In the 1950s, Édith Piaf was not only regarded as an outstanding chanson star. As a colleague, sometimes also as a temporary partner, she promoted the careers of new talents such as Yves Montand , Gilbert Bécaud and Georges Moustaki .

The philosophical-literary direction of existentialism proved to be an important source of inspiration for the post-war chanson . The writer, jazz trumpeter and chansonnier Boris Vian , an acquaintance of the writer Jean-Paul Sartres , also wrote texts for other performers. His most famous song was Le déserteur . Juliette Gréco also came from Sartre's personal circle - a singer whose lyrics were considered politically and intellectually demanding, but whose popularity fell significantly compared to those of Édith Piaf. In the 1950s , the chansons by Georges Brassens and those by the Belgian Jacques Brel were considered to be challenging and innovative . While Brassens demonstrated his left-wing political stance through regular appearances at anarchist events , Brel formulated a more nihilistic, general social criticism in his songs. Other exponents of modern chansons ( "Monsieur 100,000 volt"; most tester Hit: avancierten in the 1950 Gilbert Bécaud Natalie), Georges Moustaki, the strongly American entertainers such as Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin -oriented Charles Aznavour and singer Henri Salvador , Léo Ferré , Marcel Mouloudji , Dalida , Brigitte Fontaine and Barbara . From 1954 onwards, the converted Olympia - a Parisian music hall built in 1888 by Joseph Oller , the founder of the Moulin Rouge - became an important venue for the French chanson scene .

Stylistic diversity: 1960 to 1990

In contrast to Germany, the rock 'n' roll wave reached France relatively late. Up until the 1960s , jazz was the most important Anglo-Saxon music import - a music that was additionally popularized by several films from the Nouvelle Vague (best known example: the elevator to the scaffold from 1958). In the wake of beat music , however, a new generation of chanson performers came into the limelight. The Yéyé wave (derived from the Beatles' Yeah, Yeah ) was musically based on the music of British bands such as the Beatles, the Kinks and the Rolling Stones as well as the trends of the Swinging Sixties . Johnny Hallyday , who was heavily influenced by rock 'n' roll , Jacques Dutronc , Michel Polnareff , Joe Dassin and Julien Clerc , who acted as a French Rolling Stones epigone, gained influential status as singers and interpreters . Dutronc's future wife Françoise Hardy , France Gall and Sylvie Vartan became well-known singers of the decade . Other interpreters of the Yéyé period such as Zouzou or Adele fell into oblivion, but were rediscovered in the new millennium and re-released on some retro compilations on French pop of the sixties. As a counterpart to the Anglo-Saxon folk song wave (Joan Baez etc.) Anne Vanderlove can be seen with her quiet and melancholy songs. The songwriter and interpreter Serge Gainsbourg was pioneering for the further development of the chanson . Gainsbourg was on the one hand a versatile musician and on the other hand an equally gifted provocateur. The original title Je t'aime… moi non plus , recorded in 1967 with Brigitte Bardot and released two years later with Jane Birkin , caused a scandal , which - despite heavy criticism and boycotts - became a great international success at the end of the 1960s.

In the 1960s and 1970s , the lines between chanson and pop music became more and more blurred. This development was also promoted by the Grand Prix de la Chanson , which was strongly influenced by French-language titles until well into the 1970s. France Gall, 1965 winner with the piece Poupée de cire, poupée de son written by Serge Gainsbourg , looked like other artists to build a bridge to the Anglo-Saxon pop market and the hit market in neighboring Germany. Other artists such as Salvatore Adamo or Mireille Mathieu pursued two or even multi-track careers and made a name for themselves as pop interpreters. A special case is from the UK coming Petula Clark who first became known in France but was especially successful in the English-language and international pop market later.

The chanson scene of the 1970s and 1980s was increasingly determined by international musical styles. Conversely, the charisma that French chanson had in the 1950s and 1960s declined noticeably in the 1970s. Some hit suppliers such as Sheila switched to English-language disco music in the late 1970s . Claude François , another successful singer, learned about cover versions of popular pop titles. Other interpreters of that period such as Nicoletta (Mamy Blue), Daniel Balavoine and Michèle Torr also geared their productions strongly towards the international pop market. Bernard Lavilliers, influenced by the events of May 1968 , set opposing accents . He combined the tradition of the critical chanson with musical influences from the Caribbean , Latin America and rock elements. Other artists who continued the tradition of the (socially) critical chanson were the Parisian interpreter, composer and author Renaud and the Algerian singer Patrick Bruel . Important interpreters of the French mainstream chanson in the 1970s were mainly Julien Clerc and Michel Berger . Clerc, married to actress Miou-Miou , became known for writing the French version of the musical Hair and had a number of hits in the 1970s. Berger had written hits for Johnny Halliday, Véronique Sanson and Françoise Hardy in the 1960s and composed the French rock opera Starmania in 1978 .

Because of its stylistic diversity, the term French pop became more and more established for French pop music . It was not until the beginning of the 1980s that she was able to gain international connections. While bands like Téléphone played decidedly punk and new wave music, duos like Chagrin d'amour and Les Rita Mitsouko (hit: Marcia Baila) addressed a broader, international and at the same time young audience. The same applies to Belgian Plastic Bertrand , who landed a veritable one-time hit in 1980 with Ça plane pour moi , as well as Indochine and Mylène Farmer . The chanson was stylistically expanded to include performers from the former colonies. Well-known artists: Cheb Khaled and Sapho, who are strongly influenced by Algerian Raï and Arabic music . The music of bands such as Les Négresses Vertes and Mano Negra was more oriented towards French and international folklore . Other interpreters, such as the singer Patricia Kaas from Forbach, Lorraine , were strongly oriented towards the classical chanson, but modernized it with elements from jazz, blues and swing. The establishment of an independent French hip-hop scene played an important role in the further development of French-language music. The second largest in the world after the USA, it produced stars such as MC Solaar , Kool Shen and Joeystarr .

Development since 1990: Nouvelle Chanson

In 1994, the then French Justice Minister Jacques Toubon enforced a legal quota for French-language songs . Since then, radio stations have been obliged to use between 30 and 40 percent of the total program with French interpreters. Whether the French broadcasting quota promoted the development of the new, contemporary chanson (genre terms also: Nouvelle Chanson or Nouvelle Scène de Française) or ultimately had little effect on local music production is disputed. Unnoticed by the international market, a new chanson scene has developed since the early 1990s . Unlike the previous generations, the centers of Nouvelle Chanson were mostly in the French periphery. Stylistically, the Nouvelle Chanson was characterized on the one hand by a great variety of styles, on the other hand by the conscious recourse to features and style elements of the classical chanson.

The singer and composer Benjamin Biolay is generally considered to be the pioneer of the new scene . Other important interpreters are Dominique A , Thomas Fersen , the singer Philippe Katerine , his wife Helena Noguerra , Émilie Simon , Coralie Clément , Sébastien Tellier , Mickey 3D and Zaz . The level of awareness of the Nouvelle Chanson was greatly enhanced by the music composed by Yann Tiersen for the film The fabulous world of Amélie . The new French chanson scene also became known through the success of the new wave cover band Nouvelle Vague and the continuing influence of the chanson icon Serge Gainsbourg. Gainsbourg's death in 1991 resulted in various new works, tribute-of compilations and other accolades. The discussion about its influence on the newer chanson continued in the new millennium. Developing charisma on the current chanson, in addition to influences from lounge pop and other current electronic styles, ultimately also strong francophone pop stars such as the Canadian Celine Dion , younger pop singers such as Alizée or the singer Carla, who was married to the former French President Nicolas Sarkozy Bruni . Another indication of the unbroken acceptance of the chanson in France is the fact that cover versions of famous chanson classics from the forties and fifties are recorded again and again.

particularities

Chanson and film

The number of French chanson performers who starred in films or temporarily pursued a second career as an actor is - compared to other developed industrial nations - above average. Jacques Brel acted in a number of films between 1967 and 1973. The most successful were My Uncle Benjamin , Greetings from the kidnappers and Die Filzlaus with Lino Ventura . He directed twice himself. Gilbert Bécaud also played in several films, as well as Serge Gainsbourg (including: 1967 Anna, 1969 Slogan and 1976 Je t'aime… moi non plus) and Juliette Gréco. Charles Aznavour, descendant of Armenian immigrants, played roles in a number of internationally renowned films - including Shoot at the Pianist (1960), Taxi to Tobruk (1961), The Tin Drum (1979) and the award-winning film Ararat , which depicts the Turkish genocide addressed to the Armenians . Jacques Dutronc devoted himself mainly to his acting career in the 1970s. In 1975 he played together with Romy Schneider and Klaus Kinski in the drama Nachtblende by Andrzej Żuławski . Benjamin Biolay made his debut in 2004 in the film Why (Not) Brazil ?. He was also seen in the 2008 film Stella .

The number of French film greats who switched to the chanson profession temporarily or for longer in the course of their careers is just as impressive. These include Brigitte Bardot, Jane Birkin, Alain Delon , Catherine Deneuve , Isabelle Adjani , Julie Delpy , Sandrine Kiberlain and Chiara Mastroianni . Yves Montand's fame is based both on his reputation as a chansonnier and on the numerous roles he has played over the course of his acting career. The biographies of Édith Piaf and Serge Gainsbourg have also been filmed several times. The Spatz von Paris (1973), Édith and Marcel (1983), Piaf (1984), Une brève rencontre: Édith Piaf (1994) and La vie en rose (2007) appeared as Piaf life adaptations . The film Gainsbourg (vie héroïque) (German title: Gainsbourg) by Joann Sfar was released in early February 2010 as a free film adaptation without the claim to accurately reproduce Gainsbourg's life . Finally, there are still a few films to be shown that more or less focus on the chanson itself. Chansons play a major role in the two productions Life is a Chanson by Alain Resnais from 1997 and Chanson of Love by Christophe Honoré (2008).

Foreign interpretations and international distribution

Similar to the standard classics from the Great American Songbook , a number of chansons have become known around the world and have been covered by various artists. In France, reinterpretations of well-known chansons are an integral part of chanson culture. Even comparatively old songs are “refreshed” again and again in this way. The Eric Satie song Je te veux from 1898 was re-recorded by Joe Dassin and the Belgian band Vaya Con Dios , among others . La java bleue by Fréhel from 1939 sang among others Édith Piaf , Colette Renard and Patrick Bruel. La mer , a popular post-war chanson by Charles Trenet, was newly released in versions by Sacha Distel , Françoise Hardy, Juliette Gréco, Dalida, Patrica Kaas and In-Grid . Some remakes managed to build on the success of the original or even to catch up with it. The 2008 new version of the France Gall hit Ella elle l'a recorded by Kate Ryan , for example, made it into the top ten of several European countries.

Many chanson titles became a great success not only in France, but internationally and appeared in different versions. This is especially true of some of Édith Piaf's chansons - especially La vie en rose , which has been translated into over twelve languages. Milord , another great Piaf hit and composed by Georges Moustaki, has also been translated into several languages and has been covered many times. In addition to Édith Piaf and Georges Moustaki, Dalida, Connie Francis , Ina Deter and In-Grid interpreted the piece . A German-language version (Die Welt ist schön, Milord) sang Mireille Mathieu, an Italian-speaking Milva . The Jacques Brel song Ne me quitte pas found a similar international distribution . The German version (Please don't go away) was sung by Klaus Hofmann, Lena Valaitis and Marlene Dietrich , an English version by Frank Sinatra, Dusty Springfield and Brenda Lee ; Jacques Brel himself also has a Flemish language. The Gainsbourg-Lied Accordeon (among others by Juliette Gréco, Alexandra and Element of Crime ) Göttingen by Barbara and Tu t'laisses aller by Charles Aznavour ( Udo Lindenberg , Dieter Thomas Kuhn , as well as, under the title Mein Ideal, Hildegard Knef ). The Jacques Dutronc hit Et moi, et moi, et moi from 1965 was reissued as a bubblegum piece in the version by Mungo Jerry (title: Alright, Alright, Alright); a Hebrew version also appeared in Israel .

There was an above-average transfer of songs and artists to Germany in the 1960s and 1970s. The pop singer Mireille Mathieu, for example, relied more than average on Germanized versions of French originals. Françoise Hardy sang most of her well-known hits in German. Likewise the Belgian chanson and pop singer Salvatore Adamo. France Gall brought out their Eurovision hit Poupée de cire, poupée de son from 1965, also in a German-language version. Other cover versions of Poupée de cire played Götz Alsmann , the Moulinettes and Belle and Sebastian . German-language songs, on the other hand, left little traces in the French chanson repertoire. A well-known exception from the field of cabaret are some songs from the Threepenny Opera - especially the piece Die Moritat by Mackie Messer .

Foreign interpretations of international pop songs also played a rather minor role until recently. Charles Aznavour, who added a number of titles from the Great American Songbook to his repertoire, was the great exception among the great stars of the classical chanson era. With the advent of the Nouvelle Chanson, however, neochanson and pop artists increasingly oriented themselves towards the Anglo-Saxon pop market. A prime example is the band Nouvelle Vague, whose repertoire mainly consisted of foreign English-language compositions. However, the specifically French musical tradition also remains decisive in the Nouvelle Chanson. Along with various tribute-of compilations, songs by the late Serge Gainsbourg in particular have been covered many times in recent years.

Chanson in other countries

Germany and Austria

Due to the censorship in the German Reich , the chanson was only able to establish itself as an independent genre during the Weimar Republic . It was mainly located in the area of cabarets and variety shows and was characterized by a comparatively great freedom of movement with regard to sexual topics and its cynicism. Well-known composers of this period were Mischa Spoliansky , Friedrich Hollaender and Rudolf Nelson . The chanson writers included the authors Frank Wedekind , Marcellus Schiffer , Erich Kästner and Kurt Tucholsky , and Bertolt Brecht , Kurt Weill , Hanns Eisler and the singer and composer Ernst Busch , with a more political orientation towards workers' songs . Well-known chanson interpreters of the 1920s were Trude Hesterberg , Rosa Valetti , Gussy Holl , Blandine Ebinger , Margo Lion and Claire Waldoff .

Under National Socialism , the German-language chanson and cabaret song, as it had developed in the 1920s, was considered undesirable, and sometimes also as "degenerate" . Many well-known performers and composers went into exile - including Bertolt Brecht, Friedrich Hollaender, Rosa Valetti, co-founder of a cabaret in the artist bar Café Großerwahn on Berlin's Kudamm , and Blandine Ebinger. Marianne Oswald , who began her singing career in Berlin in 1920, had already moved to Paris in 1931, where she continued to interpret chansons by Brecht and Weill. Others withdrew into private life or smoothed their program in such a way that it passed as German light music. Some experienced prison and concentration camps or ended up - like Kurt Gerron, who became famous for his Mackie Messer interpretations, or the father of the French chanson singer Jean Ferrat - in one of the death camps . The fate of the concentration camp inmates were addressed through a global spread and in France under the title Le Chant des Déportés known song: the 1933 KZ Börgermoor caused the peat bog soldiers .

The German occupation during the Second World War and the associated repression meant a clear turning point for the French population as well. Many chanson singers were professionally and personally affected by reprisals by the occupying power and were more or less committed to the goals of the Resistance . Some, such as Juliette Gréco, were hit twice: together with her mother, a Resistance activist, she spent three weeks in the Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1943 . In France, the experience of the occupation and the associated conflicts continued to have an effect until the post-war period . Marianne Oswald, who emigrated to the USA in 1940, returned to France after the war and worked for film, radio and television. Maurice Chevalier, who had performed in front of French prisoners of war during the war, was criticized for a few years after the war for lack of commitment to the Resistance.

The German-language chanson continued to have a niche existence after the war. Schlager generally dominated the popular genre of light music. Attempts to build on the cabaret and chanson tradition of the Weimar Republic initially remained marginal. Only from the 1950s and 1960s did a chanson-oriented song culture become more prominent. Her exponents include the Munich post-war cabaret club Die Elf Scharfrichter , the Diseuse and Brecht interpreter Gisela May , the Austrian Georg Kreisler , Brigitte Mira , Fifi Brix , the Austrian Cissy Kraner and the popular Schlager interpreter Trude Herr . The demanding German-language chanson became known primarily through Hildegard Knef. The singer, guitarist and composer Alexandra made a comparable career between demanding (more) popular hits and chanson at the end of the 1960s. Udo Jürgens , Daliah Lavi and Katja Ebstein are other performers who shuttled back and forth between Schlager and Chanson or made occasional excursions into the Chanson profession .

The German-language chanson experienced a renaissance at the end of the 1960s during the Burg Waldeck Festival and the songwriting scene. On the one hand, it was strongly oriented towards Anglo-American folk. On the other hand, the musical exchange between Germany and France was comparatively large and even expanded in the 1960s. In 1964, the chanson singer Barbara published the song Göttingen - a chanson that addressed her experiences as an exchange student. The new generation of songwriters was particularly influenced by Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. The music of Franz Josef Degenhardt , Wolf Biermann and Reinhard Mey contained strong chanson elements . The latter also had some success in France. Over the years, Mey has released several records with songs in French. Other songwriters who are part of the German-language chanson of the 1970s and 1980s are Ludwig Hirsch and André Heller .

After the fall of the Wall , a German-speaking chanson scene increasingly established itself, which was influenced by younger artists. Performers who explicitly cultivate and continue the chanson tradition include Kitty Hoff , the group Nylon , Barbara Thalheim , Pe Werner , Queen Bee (the former ensemble of the musician and TV entertainer Ina Müller ), Anna Depenbusch , the chanson and jazz elements linking singer Lisa Bassenge and the Berlin duo Pigor & Eichhorn . The singer Ute Lemper became internationally known for her interpretations of Brecht, chansons and musicals . A scene that ties in with the hit and vaudeville scene of the 1920s has also become more differentiated. Well-known exponents are Tim Fischer , Georgette Dee and Max Raabe with his Palast Orchester . The latter play pieces from the repertoire of the Comedian Harmonists , which was very popular in the 1930s, with continued success . In a more liberal sense, references to chansons can also be found in the music of Element of Crime, the Berlin band Stereo Total and the songwriter Dota .

The Berlin Chanson Festival , which has been held annually since 1996, is the largest chanson music festival in German-speaking countries.

Benelux countries, Switzerland, Canada, Italy and Russia

In the Benelux countries, the chanson established itself to varying degrees. While the Walloon part of Belgium was strongly oriented towards France for linguistic reasons, the chanson is less widespread as an independent genre in the Flemish part of the country and in the neighboring Netherlands . The best-known chansonnier in Belgium is Jacques Brel. Adamo, who was born in Sicily , also became known beyond national borders in the 1960s and 1970s . Jean Vallée , the singer Viktor Lazlo and Axelle Red are also in the tradition of the French chanson . Occasionally or regularly, Jo Lemaire , the pop groups Vaya Con Dios and Pas de deux, as well as the singers Isabelle Antena and Kate Ryan performed French-language songs. The Flemish part of the country is musically strongly based on the neighboring Netherlands. Outstanding artists of the post-war decades were above all the singer Bobbejaan Schoepen, who was strongly inclined to country & western music, and the singer La Esterella, known as Zarah Leander from Flanders . Sandra Kim , 1987 winner of the Eurovision Song Contest and also quite popular in Belgium, sings a partly French-speaking, partly Flemish repertoire. In the Netherlands, the songwriter Herman van Veen can best be attributed to the chanson tradition .

There is a smaller chanson scene in Switzerland, which is mainly concentrated in the French-speaking cantons . An exception is the mani Matter from Bern , who - together with a few other chansonniers from the region, the Bernese troubadours - triggered a real dialect boom in German-speaking Switzerland. Matter inspired many singers and composers such as Tinu Heiniger , Roland Zoss , Polo Hofer and Stephan Eicher , who later gained national importance. A comparatively small chanson scene also exists in the French-speaking part of Canada, especially in the province of Québec . Well-known performers are Cœur de Pirate and the duo DobaCaracol .

There are also strong parallels to the Italian canzone . Similar to the chanson, the canzone can look back on both literary and folk song developments. Other similarities concern the status of the text and the role of the interpreter. Well-known interpreters in this sense are Paolo Conte and the singer and Brecht interpreter Milva.

The Russian chanson is a special sub-genre - known in Russian as blatnye pesni (freely translated: 'criminal songs') or simply blatnjak . The term denotes a special form of song that originated in the port cities of the Black Sea coast at the beginning of the 20th century and was particularly popular with the urban lower classes. Text structure and interpretation are very similar to the French chanson; however, there are essential country-specific characteristics. Similar to the chanson réaliste, theft and crime, prison, drugs, love, rant and the longing for freedom are strongly represented or dominant topics in Russian chanson. Murka, for example, one of the best-known pieces, recorded in innumerable versions, describes the execution of a traitor who betrayed her gang to the police. Other Eastern European musical influences are also strongly represented - in particular from the music of the Roma and the Yiddish song . Although the multicultural port city of Odessa is considered to be the place of origin of the blatnye pesni (other names referring to the origin: Odessa song or southern song), they spread over the years throughout the Soviet Union . Jazz combos from the 1920s and 1930s in particular regularly incorporated the popular Blat songs into their programs.

In the 1920s, two of the most famous Blat pieces were created - Murka and Bublitschki . After the regime more or less allowed the Blatnjak singers to do their thing until the mid-1930s, in the following decades they were increasingly forced to move to informal, semi-legal or non-legal marginal areas. The songs, which were never officially forbidden, but were ostracized during the late and post-Stalinist era, were distributed on tapes and later on cassettes . In the 1970s, Arkady Severny, who was born in Leningrad , caused a sensation. Other well-known singers are Vladimir Vysotsky , Alexander Gorodnizki and Alexander Rosenbaum . The groups La Minor and VulgarGrad as well as the performers Michail Schufutinski and Michail Wladimirowitsch Krug stand in this tradition as modern interpreters . Just like the French chanson, the Russian has mixed more and more with other styles over the years - with pop, rock and jazz as well as the bard songs, the Soviet variant of the Anglo-Saxon folk song that emerged in the late 1960s . Similarities with the French chanson resulted mainly from the repertoire. An early (French) recording of Bublitschki comes from the 1920s chanteuse Damia. With the film song Mne Nrawitsja , the singer Patricia Kaas also added a well-known piece from the Blatnjak environment to her repertoire. Above all outside the mainstream, performers of Russian pop music have increasingly resorted to this national chanson tradition in recent years. Due to the increased cultural penetration after the fall of the Iron Curtain , there is also an increased interest in Russian pop music in western countries. In autumn 2010, for example, the author Uli Hufen published a non-fiction book that introduces the history and present of the Blat chanson to a German-speaking audience. As far as current Russian pop music is concerned, the term "chanson" is not only in circulation for this particular type of song, but is also used in a more general form for more sophisticated Russian hits, rock songs or singer / songwriter music.

Feedback and reviews

Critics, musicologists, journalists and audiences have rated the chanson in very different ways throughout its history. In France itself it has been an integral part of national culture since the beginning of the 20th century. In Germany, the assessment moved in waves between reserved distance, benevolence and enthusiastic Francophilia. The Berlin theater critic Alfred Kerr wrote about the new genre around 1900: “Whatever lives outrage and happiness, they sing. In these songs there is everything, excrement and glory, heavenly and the lowest. In a word: human, human, human. ” Kurt Tucholsky reported in a more reportage-like form. In 1925 and 1926 he wrote several articles for the Vossische Zeitung and Die Weltbühne about the Parisian chanson and vaudeville scene - including an article about an appearance by chat noir legend Aristide Bruant.

In the 1950s and 1960s, reporting was predominantly determined by an interested and curious tone. The news magazine Spiegel published several current articles on the French chanson scene. While the big media of the Federal Republic often brought the specific sex appeal of the French chanson to the fore, the followers of the new critical song referred more to socially critical chanson traditions, as they emerged particularly in the music of Juliette Gréco, Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. The dispute over the scandal hit Je t'aime… moi non plus by Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin found strong press coverage at the end of the 1960s . In an article in 1969, Der Spiegel drew the following summary: “Oh yes, the loins - Gainsbourg always has them in his head, because he only loves two things and nothing else in the world: 'Eroticism and money'. And that is by no means an unhappy love: with his 'Je t'aime' he has already earned over a million francs. "

Along with the declining importance of French pop music, interest in chansons temporarily waned in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the development of the Nouvelle Chanson met with great interest, especially in Germany. This went hand in hand with a greater interest in the older stars of the genre. In January 2002 the daily newspaper published a critical article about the cult of the late Serge Gainsbourg. In an article for the magazine Sono Plus, the lifestyle author Dorin Popa pleaded for a relaxed approach to the French chanson tradition and pointed out its essentially international character: “The chanson is a deeply French myth, but its heroes are also in Egypt (Claude François, Dalida, Georges Moustaki), Belgium (Jacques Brel), Italy (Adamo, Carla Bruni, Yves Montand) or the USA (Eddie Constantine, Joe Dassin) - and they don't necessarily sing in French, but also in English and Italian , Spanish, German or in onomatopoeic gibberish: 'Shebam! Pow! Blop! Wizz! ' (Serge Gainsbourg and Brigitte Bardot in 'Comic strip'). "

Siegfried P. Rupprecht, author of the 1999 Chanson Lexicon , assessed the expressiveness of new chanson productions rather skeptically: “After its discovery as pure entertainment, many a sharp blade is blunt. In view of the laws dictated by the market, audience rates and company policies of record companies, chansons that combine humor and satire with music in an unusual way don't stand a chance. Today's chanson is sometimes critical, but no longer provocative, rather pleasing. ” The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, on the other hand, stated that the Nouvelle Chanson had innovative potential in an article at the end of 2002: “ It was a long time since experiments were carried out as spirited as in the Nouvelle Scène, cited and mixed. With the Nouvelle Scène, but also with Air , Daft Punk and Alizée, Manu Chao and the old music fighting troupe Noir Désir [...] , France is also musically becoming that new center of the present that it is in literature with Michel Houellebecq and Frédéric Beigbeder or in the cinema the film 'The Fabulous World of Amélie'. "

Well-known chansons

- Erik Satie : Je te veux (1897)

- Yvette Guilbert : Le fiacre (around 1900)

- Aristide Bruant : Nini Peau d'Chien (around 1900)

- Théodore Botrel : La Paimpolaise (1901)

- Félix Mayol : Viens, Poupoule! (1902)

- Félix Mayol : Cousin (1908)

- Mistinguett : Mon Homme (1920)

- Montéhus : La butte rouge (1923)

- Maurice Chevalier : Valentine (1924)

- Andrée Turcy : Mon anisette (1925)

- Josephine Baker : J'ai deux amours (1931)

- Fréhel : La Java bleue (1939)

- Jean Sablon : J'attendrai (around 1939)

- Édith Piaf : L'Accordéoniste (1940)

- Christiane Lorraine : Reviens moi (1942)

- Germaine Sablon : Le chant des partisans (1944)

- Édith Piaf : La vie en rose (1946)

- Charles Trenet : La mer (1946)

- Yves Montand : C'est si bon (1948)

- Juliette Gréco : L'Éternel féminin (late 1940s)

- Boris Vian (text): Le déserteur (1954)

- Georges Brassens : Chanson pour l'Auvergnat (1954)

- Édith Piaf : Sous le ciel de Paris (1954)

- Jacques Brel : Ne me quitte pas (1958)

- Édith Piaf : Milord (1959)

- Édith Piaf : Non, je ne regrette rien (1960)

- Sacha Distel : Le soleil de ma vie (around 1960)

- Gilbert Bécaud : Et maintenant (1961)

- Sylvie Vartan : Quand le film est dreary (1962)

- Gilbert Bécaud : Nathalie (1964)

- Barbara : Göttingen (1964)

- Christophe : Aline (1965)

- France Gall : Poupée de cire, poupée de son (1965)

- Hervé Vilard : Capri, c'est fini (1965)

- Jacques Dutronc : Et moi, et moi, et moi (1966)

- Michel Polnareff : La poupée qui fait non (1966)

- Gilbert Bécaud : L'important c'est la rose (1967)

- Michel Polnareff : Ta ta ta ta (1967)

- Françoise Hardy : Comment te dire adieu (1968)

- Jacques Dutronc : Il est cinq heures, Paris s'éveille (1968)

- Jane Birkin & Serge Gainsbourg : Je t'aime… moi non plus (1969)

- Joe Dassin : Les Champs-Élysées (1970)

- Séverine : Un banc, un arbre, une rue (1971)

- Michel Delpech : Pour un flirt (1971)

- Véronique Sanson : Amoureuse (1972)

- Michel Sardou : La maladie d'amour (1973)

- Charles Aznavour : She (1974)

- Dalida : J'attendrai (1975)

- Marie Laforêt : Parlez-moi d'amour (1980)

- Les Rita Mitsouko : Marcia Baïla (1984)

- Guesch Patti : Etienne (1987)

- France Gall : Ella, elle l'a (1987)

- Patricia Kaas : Mademoiselle chante le blues (1987)

literature

- German chansons , by Bierbaum, Dehmel, Falke, Finck, Heymel, Holz, Liliencron, Schröder, Wedekind, Woliehen, Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1919, DNB 572313217 .

- Siegfried P. Rupprecht: Chanson Lexicon. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-89602-201-6

- Peter Wicke, Kai-Erik Ziegenrücker, Wieland Ziegenrücker: Handbook of popular music. History - styles - practice - industry. Schott Music, Mainz 2007, ISBN 978-3-7957-0571-8

- Wolfgang Ruttkowski : The literary chanson in Germany. Dalp Collection , 99. Francke, Bern 1966 (bibliography pp. 205–256)

- Dietmar Rieger (Ed.): French Chansons. From Béranger to Barbara. French German. Reclam's Universal Library , 8364. Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-15-008364-8

- Heidemarie Sarter (ed.): Chanson and contemporary history. Diesterweg, Frankfurt 1988, ISBN 3-425-04445-1

- Andrea Oberhuber: Chanson (s) de femme (s). Development and typology of female chanson in France 1968–1993 . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-503-03729-2

- Herbert Schneider (Ed.): Chanson and Vaudeville . Social singing and entertaining communication in the 18th and 19th centuries. Röhrig, St. Ingbert 1999, ISBN 3-86110-211-0

- Roger Stein: About the term “chanson”. In dsb .: The German dirnenlied. Literary cabaret from Bruant to Brecht. 2nd edition Böhlau, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-03306-4 , p. 23ff.

- Annie Pankiewicz: Brief historique de la chanson française. In this: La chanson française depuis 1945. Manz, Munich 1981, 1989, ISBN 3-7863-0316-9 , pp. 77ff. (French cultural studies, 4.) Again in: Karl Stoppel (Ed.): La France. Regards sur un pays voisin. A collection of texts on French studies. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-009068-8 , pp. 278-280. Series: Foreign language texts (with vocabulary)

- Jacques Charpentreau: La chanson française, un art français bien à part. Foreword to: Simone Charpentreau (Ed.): Le livre d'or de la chanson française. Vol. 1: De Pierre de Ronsard à Brassens . Éditions ouvrières, Paris 1971 ISBN 2-7082-2606-1 , pp. 5ff. Again in: Karl Stoppel (Ed.): La France. Regards sur un pays voisin. A collection of texts on French studies. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-009068-8 , pp. 281–283 ( foreign language texts ) (in French, with vocabulary).

- Andreas Bonnermeier: The relationship between French chanson and Italian canzone. Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-8300-0746-9

- Andreas Bonnermeier: Women's voices in French chanson and in the Italian canzone. Publishing house Dr. Kovac, December 2002, ISBN 3-8300-0747-7

- Uli Hufen: The regime and the dandies: Russian crook chansons from Lenin to Putin. Rogner & Bernhard, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3807710570

- Steve Cannon, Hugh Dauncey: Popular Music in France from Chanson to Techno: Culture, Identity, and Society, Ashgate Publishing, 2003 ISBN 0-7546-0849-2

- Pierre Barbier, France Vernillat: Histoire de France par les chansons. Gallimard, Paris 1959 et al.

- Chantal Brunschwig, Louis-Jean Calvet, Jean-Claude Klein: 100 ans de chanson française 1880 - 1980. Seuil, Paris 1981

- Yann Plougastel, Pierre Saka: La chanson française et francophone. Larousse, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-03-511346-6

- Lucien Rioux: 50 ans de chanson française de Trenet à Bruel , éditions de l'Archipel, Paris 1991

- Gilles Verlant (ed.): L'Odyssée de la chanson française. Hors collection éditions, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-258-07087-2

- Eva Kimminich : Choked songs. Censored chansons from Paris café concerts. Attempt at a collective reformulation of social realities. (= Romanica et Comparatistica, 31). Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 3-86057-081-1 (also habilitation thesis University of Freiburg, Breisgau, 1992)

- Eberhard Kleinschmidt : Facial expressions, gestures and posture in chansons: the unjustifiably neglected visual dimension. In: dsb., Ed .: Foreign language teaching between language policy and practice. Festschrift for Herbert Christ on his 60th birthday. Narr, Tübingen 1989, ISBN 3-8233-4191-X , pp. 180–191 [To: Jacques Brel: Les bonbons '67 ]

- Eberhard Kleinschmidt: More than just text and music ... The visual dimension of the French chanson, in: Heiner Pürschel, Thomas Tinnefeld (Ed.): Modern foreign language teaching between interculturality and multimedia. Reflections and suggestions from science and practice. AKS-Verlag, Bochum 2005, ISBN 3-925453-46-6 , pp. 266-280 [To: Brel: Les bigotes ]

Web links

- French Pop , musicline.de, Genre Lexicon / Pop

- Chanson , musicline.de, genre dictionary / pop

- Chanson legend Françoise Hardy: "When I was 17 I didn't know where the babies came from" , Christoph Dallach, Spiegel Online , June 28, 2010

- Who's Who of Music / Chanson / International (overview) , www.whoiswho.de, accessed on February 12, 2011

- Romain Leick: "I was never normal". Interview with Juliette Gréco . In: Der Spiegel . No. 47 , 2003 ( online - Nov. 17, 2003 ).

- Remembering a myth: Jacques Brel is still there , Angelika Heinick, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , October 1, 2008

- Les chansons de l'Histoire de France (PDF; 1.0 MB), overview of audio CD series with historical recordings, accessed on April 28, 2016

- www.chanson-realiste.com . Website for the special genre Chanson Réaliste (French)

- The Belgian Pop & Rock Archives. Website with numerous biography entries on Belgian artists

- The regime and the Dandys website and blog of the author Uli Hufen for his book on Russian chanson

- Links for French teachers; therein a section: Chanson

- Texts, by region; z. T. also audio link

- Chansons popular

swell

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Vive la Chanson ( Memento from August 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), Dorin Popa, Sono Plus, December 2010 / January 2011 (PDF; 2.0 MB).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Siegfried P. Rupprecht: Chanson-Lexikon. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 1999. ISBN 978-3896022011 . Pages 7–15.

- ↑ Large collection of text and audio documents , 13,000 pieces, from North America in Innsbruck, Center d'étude de la chanson québécoise

- ↑ a b c d Peter Wicke, Kai-Erik Ziegenrücker, Wieland Ziegenrücker: Handbook of popular music: history - styles - practice - industry. Schott Music, Mainz, December 2006, ISBN 978-3795705718 . Page 137/138.

- ↑ The Chanson , info page www.frankreich-sued.de, called on February 18 2011th

- ↑ See also Eva Kimminich: Smothered songs. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 978-3-86057-081-4 ; Pp. 54-62.

- ↑ Eva Kimminich: Choked songs. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 978-3-86057-081-4 ; P. 80.

- ↑ Eva Kimminich: Choked songs. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 978-3-86057-081-4 ; Pp. 227 ff, 256.

- ↑ Eva Kimminich: Choked songs. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1998, ISBN 978-3-86057-081-4 ; 222 f.

- ↑ Life is a chanson. The fate of three female singers , Christian Fillitz, orf.at , April 7, 2010.

- ↑ Éditorial de la chanson réaliste , website chanson-réaliste.com, accessed on February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Heart in the throat . In: Der Spiegel . No. 14 , 1965 ( online - Mar. 31, 1965 ).

- ↑ a b French Pop ( Memento of the original from May 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , musicline.de, Genrelexikon / Pop, accessed on February 12, 2011.

- ↑ a b Song of the Loin . In: Der Spiegel . No. 42 , 1969 ( online - 13 October 1969 ).

- ↑ a b The courage of birds in the icy wind , Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , November 3, 2002.

- Jump up in detail on the two web portals www.coverinfo.de and www.discogs.com .

- ↑ a b Das obzöne Werk , Reinhard Krause, the daily newspaper , January 23, 2002.

- ↑ z. B. " Der Graben " in The Other Germany (1926)

- ^ Political chansonnier: France mourns Jean Ferrat. In: Spiegel Online , March 13, 2010.

- ↑ The muse of the existentialists: Juliette Gréco turns 80 ( Memento of the original from December 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , RP Online , February 7, 2007.

- ^ Sydney Film Festival: Collaboration and Resistance in Vichy-France , Richard Phillips, World Socialist Web Site , December 6, 2001.

- ↑ Sachliche Sehnsucht , Joachim Kronsbein Reichardt, Der Spiegel / Kulturspiegel, June 29, 2004.

- ↑ Pop / Rock / Chanson . The Belgian Pop & Rock Archives, March 2002.

- ↑ Andreas Meier Bonner: The ratio of French chanson and Italian Canzone. Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 978-3-8300-0746-3 .

- ↑ Uli Hufen: The regime and the dandies. Rogner & Bernhard, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3807710570 .

- ^ "Murka" - story of a song from the Soviet underground ( Memento from May 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), Wolfgang Oschlies, Shoa.de, accessed on March 10, 2011.

- ↑ Radio interview with Uli Hufen on the history of the Blatnjak.

- ↑ Musik auf Rippen , Christoph D. Brumme, freitag.de , February 14, 2011.

- ↑ Popular Music in Russia ( Memento from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), kultura. Issue May 5/2006 (PDF; 508 kB).

- ^ Aristide Bruant , Peter Panter ( Kurt Tucholsky ), Vossische Zeitung , January 7, 1925 (from: Tucholsky-Textarchiv on www.textlog.de).

- ^ Pariser Chansonniers , Peter Panter ( Kurt Tucholsky ), Die Weltbühne , October 12, 1926 (from: Tucholsky-Textarchiv on www.textlog.de).