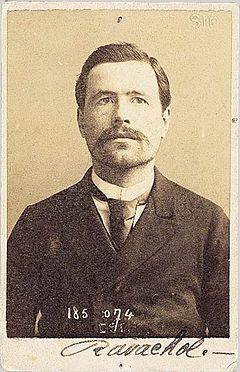

Ravachol

Ravachol (actually: François Claudius Koenigstein ; born October 14, 1859 in Saint-Chamond , Loire department ; died July 11, 1892 in Montbrison , Loire department) was a French anarchist .

Life

Ravachol was born the son of the Dutch worker Jean Adam Koenigstein and the Frenchwoman Marie Ravachol in Saint-Chamond near Saint-Étienne in eastern France. It had his mother's name because his father did not recognize it at first. Hard work from childhood and life in a society with great social differences shaped his political attitudes from an early age and made him a staunch atheist and socialist . He later joined the anarchist movement. It is reported that he temporarily lived a life as a forger and smuggler. In 1891 he was arrested and charged with the murder of a hermit. He denied the act, but confessed to some thefts and grave robberies. In 1892 he was able to flee.

On May 1, 1891, during the May Day rally in Fourmies, northern France, the military shot into the crowd, killing nine people and wounding over thirty. On the same day, the police in Clichy took action against six demonstrating anarchists who had defended themselves at gunpoint. They were sentenced to long prison terms and hard labor. As an act of revenge, Ravachol planted a bomb on March 11, 1892 in the house of the presiding judge of Clichy and on March 27 in the house of the prosecutor. In the same month he carried out another bomb attack at the Lobau barracks in Paris, where the unit responsible for the Fourmies massacre was stationed . The three attacks resulted in high property damage.

Ravachol was arrested in a restaurant where he was noticed by a waiter. On the eve of the trial against him, which began on April 26, the restaurant owner was killed when a bomb also detonated there. This was the prelude to a protracted guerrilla war between the anarchists and the government. The first sentence against Ravachol was lifelong forced labor. A short time later, Octave Mirbeau's highly regarded article on Ravachol appeared in the anarchist weekly L'En Dehors No. 52 of May 1, 1892, published by Zo d'Axa .

In 1890, Ravachol was arrested for theft. On this occasion, he was identified using the procedure developed by Alphonse Bertillon . Based on this "anthropometric signal element", his identity could be determined in July 1892. His identification brought the international breakthrough for the identification process known as Bertillonage .

Ravachol was extradited to his home district of Montbrison, where the previous murder charge was being tried. The verdict was death by the guillotine . When it was announced, he is said to have exclaimed: “Vive l'anarchie!” Ravachol was beheaded in Montbrison by executioner Louis Deibler and buried there.

Quote

During his trial he is reported to have said the following:

“It is society that produces criminals. Instead of hitting them, you jury should use your intelligence and your powers to transform society. You would abolish all crimes in one go. And because you have fought the causes, your deeds will be much greater and more fruitful than your current justice, which humiliates itself to punish the consequences. "

meaning

Ravachol is the stereotype of the bomb-laying anarchist, he stands for the so-called propaganda of action . He was so popular that a song La Ravachole was written to remember him. In French, the verb "ravacholiser" is said to have been used for "plant a bomb" or "carry out a bomb attack".

literature

- Arthur Holitscher : Ravachol and the Parisian anarchists. Die Schmiede publishing house , Berlin 1925.

Web links

- Ravachol Reference Archive. In: Marxists Internet Archive . September 12, 2009.

Footnotes

- ↑ Octave Mirbeau : Ravachol. In: Spunk Library. (English, English translation by Robert Helms).

- ↑ Martine Kaluszynski: Republican Identity: Bertillonage as Government Technique. In: Caplan, Jane John Torpey: Documenting Individual Identity. The development of state practices in the modern world. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford 2001, p. 127.

- ↑ Rik Coolsaet: Analogies of Terror: From Kropotkin to Bin Laden. In: Le Monde diplomatique . September 10, 2004, accessed September 14, 2018 (footnote 2).

- ↑ La Ravachole. In: L'Almanach du Père Peinard. 1894, accessed September 14, 2018 (French, reproduced on kropot.free.fr).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ravachol |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Koenigstein, François Claudius (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French anarchist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 14, 1859 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Saint-Chamond , Loire department, France |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 11, 1892 |

| Place of death | Montbrison |