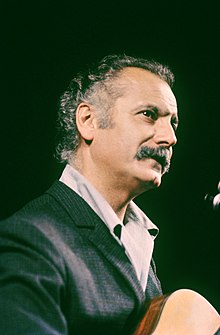

Georges Brassens

Georges Brassens [bʁasɛ̃s] (born October 22, 1921 in Sète , † October 29, 1981 in Saint-Gély-du-Fesc near Montpellier ) was a French poet and writer , but above all a famous chansonnier in the 1950s to 1970s .

Life

Brassens was the son of a small building contractor who himself came from Sète ( Département Hérault ). His mother was a very devout and music-loving Neapolitan. At the age of around 14, the young Georges began writing chansons. After breaking off his studies at the Collège Paul-Valéry in his hometown, he left for Paris in 1939 . There he lived with his aunt Antoinette Dagrosa and worked for a short time at the Renault factory in nearby Boulogne-Billancourt as an apprentice. As an early riser, he spent whole days in the library studying the masters of French poetry. In a detailed analysis of the chosen language images, themes and rhythmic cadences, he autodidactically acquired a large body of poetic knowledge. In 1942 he published 13 poems under the title A la venvole . In March 1943 he was deported to the German Reich as a forced laborer and worked in aircraft engine production in Basdorf . When he received permission to go to Paris for ten days a year later, he did not return and hid in Paris until the liberation in late summer 1944.

After the war he found accommodation in the apartment of Jeanne Le Bonniec and her husband Marcel Planche at 9 Impasse Florimont in the 14th arrondissement in Paris. Jeanne, 30 years older than him, remained his maternal friend until her death. Brassens wrote famous songs for her husband ( Chanson pour l'Auvergnat ), for her ( Jeanne ) and for her duck ( La cane de Jeanne ). The first chanson he performed in public was Le gorille , on the surface a frivolous couplet about a ruthless monkey, in its punch line a plea against the death penalty. It was later transferred and distributed in a German version by Franz Josef Degenhardt ( Caution! Gorilla ), by Jake Thackray in an English version ( Brother Gorilla ) and by Fabrizio De André in Italian ( Attenti al gorilla ).

In 1952 Brassens had his first successful public appearances in the Parisian cabaret of the famous Chanteuse Patachou , to whom he had offered his chansons. However, she decided without further ado that these would be much more useful to present himself. Due to the rapidly growing popularity, the first recordings soon followed. During the 1950s and 1960s Brassens became one of the most popular representatives of the artistic French chanson. Politically, like his colleague Léo Ferré , he was close to the anarchists , and more often he sang for the benefit of the anarchist federation "Fédération Anarchiste" and their newspaper Le Libertaire and Le Monde Libertaire .

Brassens lived a rather withdrawn life and preferred personal friends before the starry crowd. A sentence from him (from Le Pluriel ): "Where more than four people sit together, it becomes a bunch of fools." Nor did he live under the same roof with his Estonian partner Joha Heyman ( La non-demande en mariage ), whom he affectionately "dolls" called and who accompanied him on all tours and until the end of his life. After each new long-playing record was released, he performed in France for a few months.

Outside of his home country he performed twice in Luxembourg and once each in Great Britain (this concert was the only Brassens “live” recording released) and Switzerland.

In the film Porte des Lilas (in German: Die Mausefalle ) by René Clair (1956) Brassens plays the "artist" and sings some of his chansons there, including the theme song.

The 1970s were already overshadowed by serious illness. Brassens suffered from kidney cancer , had an operation in 1980 and died in 1981 near the town where he was born. He rests in the “Le Py” cemetery, opposite the “Espace Brassens” museum in Sète , which is dedicated to his life and work , not far from the beach, as he had wished for in the Chanson Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète . After his death, the Paris park near his old apartment, where he often stayed, was renamed Parc Georges Brassens in his honor .

Chansons

style

Brassens is considered one of the grand masters of the literarily demanding chanson in French culture. The charm of his chansons is a unique mixture of the language of classical French poetry and argot . The texts interweave sensitive and sarcastic thoughts, supplemented by a bitter, sometimes deliberately obscene eroticism. The music, which is often based on the swing , is subordinate to the barbaric- singer- like text presentation with less than catchy melodies . In order not to obscure the immediate effect of his lyrics, Brassens always performed his chansons (previously worked out on the piano) with the simplest instrumentation: his acoustic guitar and the bass of his constant concert accompanist Pierre Nicolas.

In addition to his own texts, he also set works by French poets from various eras such as François Villon ( Ballade des dames du temps jadis ), Louis Aragon , Victor Hugo , Lamartine , Paul Verlaine and Paul Fort .

subjects

Although Brassens had written under various pseudonyms for anarchist newspapers before his career as a chansonnier, he did not write politically committed chansons like other of his colleagues, such as Leo Ferré or Jean Ferrat . He did not believe in changing society with a "little chanson". In addition, his view of life was strongly individualistic and not collectivistic, his conception of anarchy more that of a libertine , for which the personal freedom of the individual is paramount. Mourir pour des idées addresses his skepticism about dying for ideals. In the dispute between two politically dogmatic uncles, one on the side of the British and the other on the side of the Germans, Les Deux Oncles takes a position for its own middle path that rejects any nationalism. Le Temps ne fait rien à l'affaire shows people predetermined and unteachable through history. Grand-père and La Rose, la bouteille, et la poignée de mains lament a general moral decline.

One of the few chansons with which Brassens contributed to a contemporary political debate is Le Gorille , in which he uses humor to express his disapproval of the death penalty and the judges who imposed it. In general, the representatives of law and order are often the target of criticism and ridicule, for example in Hécatombe , where a group of market women massacred a police patrol. Between 1952 and 1964, almost half of Brassens' chansons were banned from the state radio station RTF because they either attacked the police and the judiciary or were considered offensive. Brazen's joy in provocation for its own sake is shown by the round of curses in La Ronde des jurons . In other songs he describes himself as a “pornographer of music” ( Le Pornographe ) or “weed” ( La Mauvaise Herbe ) and plays with his bad reputation ( La Mauvaise Reputation ), which in Les Trompettes de la Renée has become something like his trademark that the scandal press expects of him.

Brassens' outstanding love of freedom is also evident in his love songs, in which marriage is always presented as a negative social construct that restricts the freedom of love ( La Non-demande en mariage , La Marche nuptiale ). Love itself can take on romantic and tender expressions, such as the devoted kneeling in Je me suis fait tout petit , but mostly remains down-to-earth and often humorous. Brazen's narrators take life and women as they are and can also deal with loss and infidelity. In Les Amoureux des bancs publics , an older man observes young lovers on park benches and predicts the end of their love affair. In Embrasse-les tous , in spite of all their crimes, women are the cure for all diseases. Brassens does not shy away from the use of explicit sexual language, for example in Quatre-vingt-quinze pour cent . A notable exception is Le Blason , a song entirely dedicated to the female genitals, but euphemistically paraphrasing them in many ways. Brassens responded to accusations of misogyny in a typical way with the provocative and ironic chanson Misogynie à part , which also questions the equation of chansonnier and chanson.

In Brassens' chansons, death is just as important as love. Brassens was agnostic and made fun of blind faith in songs like Le Mécréant . He also treats death in a burlesque way in songs like Les Funérailles d'antan and La Ballade des cimetières . In others like Bonhomme , it becomes a natural part of life. In Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète , Brassens, alluding to Édith Piaf's death, wishes to officially die in his hometown of Sète. Brassens had the song in his repertoire until his own death. In his chansons, home always serves as a place of refuge, for example when he longs for the tree in his garden in Auprès de mon arbre . Another spiritual home for Brassens, who did not see himself as a person of the twentieth century, is past ages, especially the Middle Ages , which he sings about in Le Moyenâgeux , for example . However, its cultural frame of reference extends even further back to antiquity. For example, Cupid , the Roman god of love, appears in songs like Cupidon s'en fout or Histoire de faussaire .

Public perception and impact

Both on stage and in documentaries about his life, Brassens cultivated the image of an ordinary person to whom starry airs are alien. His demeanor was modest and reserved, his simple presentation and the sparse instrumentation created a feeling of intimacy and authenticity in the audience. Brassens also underlined this image with a series of visual motifs that he used repeatedly in pictures, record covers and in film recordings: his distinctive mustache, the always present pipe, his guitar and cats, with which the big cat lover always surrounded himself, and one Let the multitude of subliminal meanings resonate, especially for the chansonnier's relationship with women. All in all, they conveyed the image of a lovable, down-to-earth and a little obnoxious southern French working class.

At the same time, Brassens appealed to a liberal audience of the 1950s and 1960s with his nonconformism and satires directed against the establishment, who repeatedly expressed their approval of his ironic tips with laughter and applause and were amused by his uninhibited use of the vulgar argot. Both the media and the audience in his concerts expected from Brassens, who was known for not mincing words, a mischievous and controversial take up of social taboos.

Brassens was one of the most important and influential chansonniers of the 20th century. In France he was considered an institution in the tradition of sung poetry. To date, more than 30 million CDs and LPs of his chansons have been sold. In 1967 the old Académie française awarded him the Grand Prix de Poésie . In a poll in the late 1960s for the most important figure to identify with, two thirds of the French questioned said they would like to be Georges Brassens.

From the German songwriting scene, Reinhard Mey , Wolf Biermann , Franz Josef Degenhardt , Dieter Süverkrüp , the early Hannes Wader ( Hannes Wader sings ... ), Walter Mossmann and the Swiss dialect songwriter Mani Matter , who all name him as their role model, are closest to him .

Discography

From 1952 his chansons were published first by Polydor , then from 1953 by Philips on records in different formats and always in new compositions. The 14 original LPs released during his lifetime are usually listed with the title of their first chanson:

- La Mauvaise Réputation (1952)

- Le Vent (1953)

- Les Sabots d'Hélène (1954)

- Je me suis fait tout petit (1956)

- Uncle Archibald (1957)

- Le Pornographe (1958)

- Les Funérailles d'antan (1960)

- Le temps ne fait rien à l'affaire (1961)

- Les trompettes de la renownedée (1962)

- Les Copains d'abord (1964)

- Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sête (1966)

- Misogyny à part (1969)

- La Religieuse (1972)

- Trompe-la-mort (1976; also Nouvelles chansons )

29 chansons that he himself had not recorded or completed during his lifetime were interpreted by Jean Bertola :

- Dernières Chansons (1982, double LP)

- Le Patrimoine de Brassens (1985)

In 1974 a live recording of a concert on October 28, 1973 in Cardiff was released:

- Georges Brassens in Great Britain

In 1979 a double LP was released with jazzed Brassens chansons:

- Georges Brassens joue avec Mustache et Les Petits Français

In 1980 Brassens made a record with older French chansons:

- Georges Brassens chante les chansons de sa jeunesse

The following have appeared from the estate :

- Brassens chante Bruant , Colpi , Musset , Nadaud , Norge (LP, 1984)

- Georges Brassens au TNP (CD, 1996)

- Georges Brassens à la Villa d'Este (LP, 2001)

- Bobino 64 (CD, 2001)

- Inédits (CD, 2001)

- Concerts from 1959 à 1976 (6 CDs, 2006)

For compilations, chart successes and awards for music sales see Georges Brassens / Discography .

bibliography

- Les Couleurs vagues . Poems, 1941/42; New edition: Librio, Paris 2010, ISBN 978-2-290-02170-5 .

- À la venvole . Poems. Private print 1942.

- La Lune écoute aux portes . Novel. Private print 1947.

- La tour des miracles . Novel. Paris 1953; New edition: Librio, Paris 2010, ISBN 978-2-290-02169-9 .

- La mauvaise réputation (selection). Paris 1954.

- Chansons . Sand et Tchou, Paris 1968.

-

Poèmes et chansons . Seuil, Paris 1991; Points, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-7578-0957-0 .

- German edition: Chansons. The complete work . Texts in French / German, transferred by Gisbert Haefs . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 1996. Contains an afterword and a detailed bibliography and discography (also published as an additional volume: Scores )

- Œuvres complètes . Le Cherche midi, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-7491-0834-6 .

- Les chemins qui ne mènent pas à Rome. Reflections et maximes d'un libertaire . Le Cherche midi, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-7491-1142-1 .

literature

- Thomas Dobberkau: Georges Brassens. Poet and bard or heretic and rebel? In: Ernst Günther, Heinz P. Hofmann, Walter Rösler (eds.): Cassette. An almanac for the stage, podium and ring (= cassette ). No. 3 . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1979, p. 191-198 .

- Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson . Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 2005, ISBN 0-85323-758-1 .

Web links

- Georges Brassens in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Georges Brassens in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Website of the Brassens Association in Basdorf with various information, e.g. B. about the annual festival

- ↑ Espace Brassens , espace-brassens.fr, accessed March 18, 2012

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson , pp. 127, 154-155, 171-174.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson , pp. 137-143, 172-173.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson , pp. 62-67, 70-71, 82, 95-97.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson , pp. 11-15, 21, 36-37, 44-52.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson , pp. 80, 146.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson , pp. 72, 137-138, 143-144.

- ^ Gisbert Haefs : Afterword . In: Georges Brassens: Chansons. The complete work . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 1996, p. 779.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Brassens, Georges |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French poet and chansonnier |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 22, 1921 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sète , France |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 29, 1981 |

| Place of death | Saint-Gély-du-Fesc near Montpellier , France |