Jacques Brel

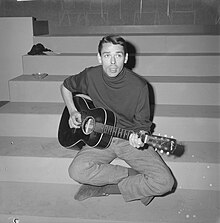

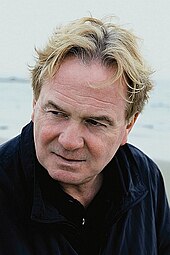

Jacques Romain Georges Brel ( ; born April 8, 1929 in Schaerbeek / Schaarbeek , Belgium ; † October 9, 1978 in Bobigny , France ) was a Belgian chansonnier and actor . His songs, mostly in French , made him one of the most important representatives of French chanson . With Charles Trenet and Georges Brassens he occupies a prominent position among the chansonniers who perform their own songs. The themes of his chansons cover a wide spectrum from love songs to harsh social criticism . His performances were characterized by an expressive, dramatic presentation. Numerous other singers interpreted Brel's chansons such as Ne me quitte pas , Amsterdam , Le plat pays , La chanson de Jacky or Orly and translated them into other languages, including the international hit Seasons in the Sun (originally Le Moribond ). Well-known Brel interpreters in German are Michael Heltau and Klaus Hoffmann .

Growing up in Brussels, Brel went to Paris in 1953 in the hope of a career as a chansonnier . In France he only sang on small stages and toured the provinces for a long time until his breakthrough at the end of the 1950s and he became one of the greatest contemporary stars of the chanson scene. At the height of his career, Brel stepped down from the stage in 1967. He then transferred the musical The Man of La Mancha into French, in which he himself took on the role of Don Quixote . He played in ten feature films, two of which he directed himself. After the failure of his second film, he largely withdrew from the public eye and indulged in two private passions, aviation and sailing . In 1976 he settled on Hiva Oa , an island in Polynesia , from which he returned to Paris in 1977 to record his last record after a long artistic break. The on lung diseased Brel died the following year.

Life

Youth in Brussels

Jacques Brel was the youngest child of Romain Brel (1883–1964) and his wife Elisabeth, née Lambertine (1896–1964). A pair of twins died shortly after birth in 1922, the older brother Pierre was born in 1923. Romain Brel, a French-speaking Flemish , worked in the import / export industry and lived temporarily in the Congo before becoming a partner in his brother-in-law's cardboard factory , which from then on operated under the name of Vanneste & Brel and has since been taken over by SCA . Elisabeth, called "Lisette", came from Schaerbeek , where her sons grew up. The father was seen as reserved and silent, his wife 13 years younger than spirited, enterprising and soulful. "Jacky", as little Jacques was called, described his sheltered childhood in the middle class family in retrospect as marked by loneliness and boredom. His chanson Mon enfance begins with the verses:

"Mon enfance passa

De grisailles en silences"

"My childhood passed

in everyday gray and silence"

From 1941 on, Jacques went to the Institut Saint-Louis private school . He was a poor student and had to repeat grades several times. Up for all sorts of pranks and creating a good mood, he was just as popular with his classmates as he was in his scout group . His play in the school theater group that he helped set up showed a tendency to exaggerate. Brel, who read a lot - he was particularly influenced by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry - and tried to play the piano without any musical training, wrote a few young novellas and his first song at the age of 15. When the third repetition of the ninth grade was threatened in 1947, his parents took him from school. The son began to work in the family's cardboard box factory, where he was faced with a civil career that he found dreary and mediocre.

Brel found his spiritual home at this time in the Catholic youth movement Franche Cordée around its founder Hector Bruyndonckx. In 1949 he assumed the presidency of the group. This was determined by Christian moral principles, but it also enabled an interdenominational exchange of ideas and promoted social activities such as caring for children from poor neighborhoods or cultural appearances in hospitals and old people's homes. Brel sang his first guitar songs in the group, and he met Thérèse Michielsen, two years older than him, known as "Miche", whom he married on June 1, 1950. The couple had three daughters: Chantal (1951–1999), France (* 1953) and Isabelle (* 1958).

Meanwhile, Brel grew tired of the monotonous work in the factory. After an argument with his father, the outbreak fantasy Il pleut arose :

"Les corridors crasseux sont les seuls que je vois

Les escaliers qui montent ils sont toujours pour moi"

"The stairs that lead up are always for me.

The dirty hallways are the only ones I see"

Brel felt the urge to go to the stage to perform the songs he had written. He appeared in small clubs in the Brussels area and took part in competitions unsuccessfully, for example in the seaside resort of Knokke , where he came second to last. At his father's request, he temporarily took the stage name "Bérel". Brel found support from the radio presenter Angéle Guller, whom he accompanied on lecture tours and whose acquaintance in February 1953 led to a first recording at Philips . The single with the two songs La foire and Il ya only sold 200 copies, but Jacques Canetti , the artistic director of Philips, noticed Brel and invited the young singer to Paris . The father accepted a one-year career break for his son, Miche agreed to the temporary separation, and Brel traveled to the metropolis of the chanson in early June 1953 in the hope of a breakthrough.

Chansonnier in Paris

For a long time, Brel found it difficult to gain a foothold in the French capital. In retrospect, he described: "I made my debut for five years." Because of his looks, Canetti advised the singer to stay backstage and write for other performers. Rejections because of Brel's supposed ugliness ran through his life and are a frequent topic in the chansons. Brel's stage presence also seemed awkward and provincial. Nevertheless, Canetti made the first appearance in his theater Les Trois Baudets possible in September 1953 . Numerous other applications in cabarets and radio were mostly unsuccessful. After all, some of his more famous colleagues stood up for him, such as Georges Brassens , who had a changeful friendship with Brel throughout his life, and Juliette Gréco , who made his song Le diable (Ça va) famous. In February 1954, Canetti produced Brel's first long-playing record, but the reviews were negative, so the Paris-Soir wanted to send the Belgian back home by train by return mail. At his first, less successful appearance at the legendary Olympia in June 1954, Brel sang in the opening act. It was not until seven years later that he celebrated success there as the star of the event; he stood in for the sick Marlene Dietrich .

In the summer of 1954 Canetti Brel engaged for the first time for a tour. He began to find a taste for touring life, the daily trips and evening appearances on provincial stages in France, Belgium or North Africa. He started a short liaison with his touring partner Catherine Sauvage . On a tour in the summer of 1955, he met Suzanne Gabriello , known as "Zizou", with whom he had a passionate love affair with numerous breakups and reconciliations over the next five years. The relationship was not tarnished when Miche came to Paris with the children temporarily to support her husband, before she finally returned to her home in Brussels for the birth of her third child and lived apart from her husband for a few weeks each year. Gabriello later claimed that Brel wrote his famous chanson Ne me quitte pas for her.

"Ne me quitte pas

Il faut oublier

Tout peut s'oublier

Qui s'enfuit déjà"

"Don't go away from me

and forget what happened

if you can forget

the past"

The song Quand on n'a que l'amour was Brel's first sales success in 1956. The hymn about the power of love reached number three on the French charts and received the Grand Prix du Disque of the Charles Cros Academy . In the same year, Brel met the pianist and composer François Rauber , who was responsible for arranging his songs. Two years later, the pianist Gérard Jouannest joined them, and in 1960 the accordionist Jean Corti , who was later replaced by Marcel Azzola . Through their collaboration, Brels Chansons received new impulses, many songs were created jointly. In addition, his accompanying musicians allowed Brel, freed from the obligatory guitar, to develop more freely on stage. Using his whole body, he increasingly succeeded in captivating the audience, for example when he played the main program for the first time in front of enthusiastic spectators in the Bobino , next to the Olympia one of the great Parisian music halls of that time. Brel performed up to three hundred concerts a year on his tours, while many of his most famous chansons such as Amsterdam , Mathilde or Ces gens-là were recorded in the hotel rooms .

In 1959, Brel finally achieved the breakthrough. With the concert successes, the sales of his records increased and he received numerous honors. From 1962 onwards, his chanson texts found their way into schools as teaching material. On March 7th of that year, Brel left his previous record company Philips and switched to Barclay Records , which caused a sensation: It was rumored that a contract was for life, but French law only allowed a 30-year contract, which was later extended. Brel led a double life privately. Since 1960 he lived in Paris with the press secretary of a record company, which he left in 1970 to enter into a relationship with her friend. Nevertheless, he remained married to Miche, who took care of business matters, about Brels founded Éditions Pouchenel in 1962, which marketed his songs. The chansonnier regularly visited his family in Brussels, where he showed himself to the children as a conservative family man who was hardly able to convey the tenderness that can be felt in chansons like Un enfant, especially towards children:

"Un enfant

Ça vous décroche un rêve"

"A child

that brings you a dream to light"

He remained more loyal than women to his friend Georges Pasquier, known as “Jojo”, who did not leave Brel's side during these years, had lively political discussions with him and acted as Brel's “man for everything”. In 1964, Brel's parents died in quick succession. A year earlier, Brel had written the chanson Les vieux :

"Et l'autre reste là, le meilleur ou le pire, le doux ou le sévère

Cela n'importe pas, celui des deux qui reste se retrouve en enfer"

“And the other one stays there, who was the better, maybe also was worse.

No longer important for him, because for those who stay there, hell is there. "

Retreat and new projects

In 1965, Brel had long since achieved the status of a figurehead for Francophone culture abroad. After successes in Switzerland and Canada, he toured the Soviet Union and the USA. Performances in New York's Carnegie Hall followed in 1966 at London's Royal Albert Hall . While still in London, at a celebratory dinner with Charles Aznavour , Brel expressed his intention to leave the stage for the first time: he had reached a climax from which it could only go downhill, but he did not want to cheat his audience. In October 1966, for the last time at the Olympia , Brel's farewell tour began, which he concluded with his last public concert on May 16, 1967 in Roubaix .

Even after he left the stage, the audience's interest in Brel and his albums remained high. In 1968 he released his - for the time being - last record, introduced by the chanson J'arrive . In the same year Brel himself became the subject of a play entitled Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris , in which Mort Shuman and Eric Blau translated his chansons into English in the form of a musical . The production became an international success. Brel, however, understood it as a kind of obituary and avoided going to a performance for a year. Another musical brought him back to the stage in 1968, albeit with strange songs. Brel translated the American production Man of La Mancha by Mitch Leigh , Dale Wasserman and Joe Darion into French and took on the lead role in the several months of performances in Brussels and Paris. Brel felt immediately connected to the figure of Don Quixote between rebel, dreamer and fool, and he interpreted his “impossible dream” in the chanson La quête with fervor:

"Brûle encore, bien qu'ayant tout brûlé

Brûle encore, même trop, même mal

Pour atteindre à s'en écarteler

Pour atteindre l'inaccessible étoile."

"Still burns even after he has burned everything.

Still burns, even too much, even badly

Until he divides himself into four to reach

him. To reach him, the unreachable star."

Another musical for children, which was planned under the title Voyage sur la lune and was based on new songs by Brel, was canceled two days before the premiere in 1970 because it did not want to give up his name for the unsatisfactory implementation.

In the following years, Brel moved from the stage to the screen. Between 1967 and 1973 he played in a total of ten feature films, including My Uncle Benjamin on the side of Claude Jade and Die Filzlaus next to Lino Ventura . In 1971 , while filming Die Entführer let greet , he met Maddly Bamy , a young woman from Guadeloupe , with whom he entered into a third parallel relationship. The few chansons that Brel wrote during these years were mainly used as background music for the films. His artistic ambitions were two film projects, which he realized according to his own script and under his own direction. Franz , a low-budget production with Brel's chanson colleague Barbara , is a film about an unhappy love triangle. The film did not reach a wide audience, but the personal signature of the author's film received respectful reviews. In contrast, Le Far-West , Belgium's contribution to the 1973 Cannes Film Festival , turned out to be a complete failure . The story of a group of people in the Wild West looking for the lost paradise of their childhood was not understood by either the audience or the critics.

Departure for the South Seas

After the failure of Le Far-West , Brel withdrew from film and largely from the public. In the following years he devoted himself primarily to two private passions, aviation and sailing . As early as 1964, Brel had acquired his license and his first small aircraft from the Gardan Horizon brand , followed in 1970 by the license for instrument flight . Since 1967 he owned a sailing ship with which he made numerous trips; in 1973 he crossed the Atlantic for the first time . In the chanson L'ostendaise, Brel, more and more tired of life in human community, contrasted his outburst with the regulated life plan of society:

"Il ya deux sortes de gens

Il ya les vivants

Et moi je suis en mer."

"There are two kinds of people

The living ...

And I'm at sea."

At the beginning of 1974 he planned a five-year circumnavigation of the world accompanied by his daughter France and his lover Maddly. But the trip with the newly acquired Askoy II was interrupted twice right at the beginning in the Azores and the Canary Islands . First, Brel's long-time friend Jojo died, and he was traveling back to his funeral, then Brel was diagnosed with lung cancer after a collapse and had to undergo an operation in Brussels that removed part of his lungs. Nevertheless, Brel did not abandon his travel plans and started six weeks after the operation for the Atlantic crossing to Martinique , where France left the ship in January 1975 after disputes on board and Brel sailed on alone with Maddly in the direction of the Pacific Ocean .

Influenced by Robert Merle's novel L'île , Brel had long cherished the dream of a life far from civilization. As early as 1962 he had given words to his longing in the chanson Une île :

"Voici qu'une île est en partance

Et qui sommeillait en nos yeux

Depuis les portes de l'enfance"

"An island that lifts its anchor

and that has

slumbered in our eyes since the gates of childhood "

He found his island in Hiva Oa , one of the Marquesas islands where the painter Paul Gauguin had once spent his last years. In June 1976 Brel rented a house in the village of Atuona , where he and Maddly settled. In the following year he applied to the Polynesian authorities for permanent residence on the island. Brel sold his boat and acquired a Twin Bonanza aircraft , which he named Jojo . He regularly flew to Tahiti and made himself useful on the islands, for example by transporting mail to Ua Pou . In the seclusion of the Marquesas, Brel found the inspiration for new chansons that revolved around his retreat, but also repeatedly about approaching death.

To record the chansons, Brel traveled back to Paris in August 1977, where he met his old companions again and sang his last record, marked by the disease. This sparked an enormous response after the long artistic break. A million pre-orders were received before they were even shipped. In his home country of Belgium, Les F… , a blacksmith against the Flemings, caused another scandal, but Brel was already on his way back to his island at this point. He felt persecuted by French journalists who tried by all means to get photos of the cancer-stricken singer, and in September obtained the confiscation of an edition of the Paris Match magazine . By July 1978, Brel's health had deteriorated so much that he had to return to Paris for chemotherapy . He recovered for a few weeks in Geneva and planned to move to Avignon , but with signs of pulmonary embolism , he was transported back to Bobigny near Paris on October 7 , where he died of heart failure two days later . His body was transferred to Hiva Oa and buried not far from Gauguin's grave.

Chansons

Jacques Brel performed almost exclusively his own chansons. In the course of his career he published around 150 recordings. Five chansons he had sorted out during the production of his last record were only released posthumously in 2003. For a list of his works, see the list of chansons and publications by Jacques Brel . In addition to his own songs, Brel wrote seven chansons for other performers that he did not include in his own repertoire, see also the list of performers for Jacques Brel's chansons . He also wrote lyrics for two musicals. Brel registered a total of 192 song lyrics with the French collecting society SACEM over a period of 25 years.

Texts

There are extensive debates about the question of the extent to which chansons in general and Brel's chansons in particular should be understood as poetry , particularly through the publication of the texts by Brassens and Brels in the early 1960s in the series Poètes d'aujourd'hui of the Seghers edition were fanned. Although numerous voices confirm the poetic nature of his chansons, Brel himself rejected the term poetry. Compared to other great chansons such as Georges Brassens , Charles Trenet and Leo Ferré , Brel's chansons are generally considered to be less literary and have a stronger effect due to their scenic performance. Nevertheless, Brel's chanson texts in particular have now been canonized in literary terms and appear in French textbooks alongside Brassens and Jacques Prévert . They were repeated exams in the Baccalauréat .

While Brel's early, more idealistic chansons are characterized by lyrical style elements, the later work is dominated by dramatic chansons, which require a theatrical interpretation on the stage. They are based on two different, sometimes combined, stylistic devices: on the one hand, the dramatic arrangement of a situation and its development - for example in Madeleine , Jef or Les bonbons - and on the other hand the heightened dramatic expression of human feelings - for example in Ne me quitte pas , La Fanette or J'arrive . In addition, Brel often tells fables - but rarely animal fables like Le cheval or Le lion, for example - and rarely parables like Sur la place or the strongly encrypted Regarde bien, petit . He prefers to use caricature and satire to depict society .

Brel's language is the standard French language that is often adapted for colloquial use. In contrast to Brassens and Ferré, he uses neither vocabulary nor rhetorical means of high style. He also lacks their intertextual references to literature and mythology. Wherever Brel uses such references, they mostly stay within the world of the chanson. Like Prévert, Brel has a penchant for simple poetic images, so his “ feuilles mortes ” appear several times . The most striking stylistic means is a multitude of neologisms , which, according to Michaela Weiss, are characterized by their conciseness and clarity and are often anthropomorphisms . In addition, the structural repetitions of words are particularly noticeable. The syntax shows frequent ellipses and sentence changes compared to the usual language usage. Brel is based on traditional meter measures , but handles the metric irregularly and flexibly adjusts it if necessary.

For Sara Poole, a large part of the effect of Brel's chansons lies in their ambiguity , which appeals to the listener's imagination to shape them using their own imagination. A chanson like Ces gens-là, for example, only sets a frame, filled with realistic details and the underlying relationships and emotions, but each listener creates a different image of “these people there”. The “Sons of November”, who return to Le plat pays in May, can be understood as sowing in the fields, seafarers on long voyages or migratory birds. In Je ne sais pas it remains unclear which of the three people form a couple and who is actually leaving whom. La Fanette not only leaves the fate of the beloved open, it is also sufficient to exchange a single letter in an otherwise identical sentence to completely change the fate of the protagonists (“m'aimait / l'aimait” - “loved me / loved him "). Brel often uses symbols , such as water in all its variations, with the positive meaning reserved for flowing, unlimited water. Animal metaphors as in Les singes or Les biches are used almost exclusively to illustrate negative traits in people, with the exception of the horse in Le cheval , which stands for unbridled masculinity. The contrast between statics and dynamics not only plays an important role in Brel's work in terms of content, but is also reflected in the formal construction. Many chansons deal with the situation of waiting, social and regional changes, especially the motive of traveling, have a positive connotation.

music

While Brel always wrote his lyrics by hand, he remained dependent on collaboration with other musicians for the musical implementation. The chansonnier, who autodidactically taught himself to play the guitar and organ, could neither read sheet music nor work out scores , so that at the beginning of his career various orchestra leaders took over the musical arrangement . André Grassi and Michel Legrand orchestrated in the typical big band sound of the time, André Popp more cautiously and with more emphasis on Brel. The collaboration with François Rauber and Gérard Jouannest , who had been responsible for the arrangement of his chansons since 1956 and 1958 and composed some of the music, had a decisive influence on Brel's style . Both had different ways of working: While Rauber always worked with the finished text, Brel and Jouannest mostly developed the text and music together. Brel already had clear ideas about the right music, rhythm and melody when writing the chanson texts. His musicians called this a “visual imagination”, which Brel then conveyed to them, while Rauber, Jouannest or Jean Corti brought in their own ideas according to Brel's specifications and continued to refine the chansons as they worked together.

Brel sang in the register of a baritone and mastered a large range. The publicist Olivier Todd describes his voice as “that of a talented amateur - clear, but without volume.” At first he had a slight Brussels accent, which he made fun of himself in Les bonbons 67 . According to Thomas Weick, his vocal performance ranged from the subtle singing with timbre in Le plat pays to the rough, latently monotonous, tearful voice in Je ne sais pas to the voluminous, powerful lecture with a cracking voice in Amsterdam . The dominant instruments in Brel's Chanson are the piano and the accordion . For coloring , other instruments are used, such as shepherd's flute and bugle to characterize the environment in Les bergers , strings and harp for the movement of the sea in La Fanette . There, with the Ondes Martenot , one of the sparingly used electronic instruments is also used. Over the course of his career, Brel changed the instrumentation of some chansons several times. For example, the early hit Quand on n'a que l'amour is available in addition to the original version from 1956, a newly arranged live version from 1961 and a lavishly recorded version from 1972 in the studio.

In his chansons, Brel liked to use well-known basic musical forms such as the waltz , Charleston , tango or samba , which, however, are often alienated. The waltz in La valse à mille temps, for example, constantly increases in tempo, and the Samba Clara is in the unfamiliar 5/4 time. The tangos in pink or Knokke-le-Zoute tango underline the content, in the first case the school domestication of young people, in the last a caricatured debauchery in the style of Tango Argentino . Titine, on the other hand, parodistically quotes the Charleston Je cherche après Titine from 1917. Quotes from classical music can also be found again and again, for example the piano prelude in Ne me quitte pas is reminiscent of the Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody by Franz Liszt or L'air de la bêtise of arias in the style of Rossini . The style quotations mostly serve as ironic or parody.

Lecture

Brel's stage performances have often been described in drastic terms. Le Figaro spoke of a “hurricane called Brel”, and Der Spiegel characterized the chansonnier during his performances as “ [e] mphatic and impetuous like a singing animal”, to go on to explain: “Brel grimaced and waved when he stepped in front of the audience, and he sang with pathetic vigor, sometimes frivolous and casual, sometimes noisy , often restrained, mostly aggressive and sometimes with a great taste for the macabre ”. According to Olivier Todd, Brel slipped into all of his characters during his appearances, transformed from a drunken sailor in Amsterdam to a bull in Les toros . He sang, “boxing like a boxer”, excreted a large amount of sweat during his performances and exerted himself so much that - according to measurements by Jean Clouzet - he lost up to 800 grams in an hour and a half.

Brel's programs usually consisted of 15 or 16 chansons that followed each other without moderation. Brel refused to give encores on principle, which he compared to an actor who was not asked to perform a scene again. He mostly appeared in a neutral black suit, which drew the audience's attention to his facial expressions and gestures . After he accompanied himself on the guitar at the beginning of his career, in later years it only played a role as a prop in individual chansons such as Quand on n'a que l'amour and Le plat pays . At that time, Brel's appearances were rather characterized by an expressive, dramatic lecture in front of a standing microphone, which Michaela Weiss describes as simultaneously “intense” and “ excessive ”. Brel is not concerned with creating an illusion, but consciously uses stylization and caricature exaggeration , whereby he is not afraid of the effect of ridicule. But he also retains a feeling for fine differentiations when, for example, in the Chanson Les vieux the expansive movement of a pendulum - as a symbol of the passing of time - is contrasted with the trembling of the hands of the ancients. Despite such rehearsed gestures, Brel allowed himself to be carried away again and again into spontaneous improvisations during the lecture, as a comparison of different recordings of the same song shows.

Robert Alden commented on Brel's performance in New York's Carnegie Hall that the American audience, even without language skills, was able to understand the content of the songs on the emotional level simply because of Brel's lecture, his use of voice, hands and body to be captured by him. Brel's pianist Gérard Jouannest, who accompanied him at his concerts, also described how the spark of Brel's emotional lecture jumped over to his audience every evening. Brel's compressed “miniature dramas” required the full attention of his listeners and stood in the way of incidental consumption as hit music or dance music . Brel set himself apart from the style of a crooner like Frank Sinatra . His chansons were designed with the stage effect in mind from the drafting of the text. There are dramatic elements such as onomatopoeia , for example the onomatopoeic slurping in Ces gens-là , or punch lines, such as the exuberant word “con” in Les bourgeois , which Brel later used effectively on the stage.

subjects

Faith, agnosticism, humanism

Brel's beginnings as a chansonnier were still strongly influenced by his Catholic origins and, in particular, the influences of the youth organization Franche Cordée . A Christian - idealistic worldview was also found in his songs , so that Brassens coined the nickname "l ' abbé Brel" for his colleague . Michaela Weiss traces the content of many early chansons back to the formula "love, faith, hope". Evil does indeed manifest itself in the world of his songs, of which Brel lets the devil report personally in the chanson Le diable (Ça va) . But the belief in people and their ability to realize the ideal of a better world remains unbroken, as the hymn Quand on n'a que l'amour conjures up. However, the first signs of skepticism can be seen in the early chansons . In his quest for faith in Grand Jacques , Brel explicitly turns against traditional ecclesiastical recipes:

"Tais-toi donc, grand Jacques

Que connais-tu du Bon Dieu

Un cantique, une image

Tu n'en connais rien de mieux"

"Be quiet Grand Jacques

because what do you know about God

A chorale an icon

Nothing about life Nothing about death"

For Chris Tinker, the young, naive-romantic Brel only used a loose Christian framework to package his moral agenda, which is in chansons like L'air de la bêtise , Sur la place and S'il te faut against the ignorance of the people directs. In the course of the work, Brel, who called himself an atheist in late interviews , took on the position of agnosticism more and more . In the chanson Seul, the human being is ultimately thrown back on himself and an absurd existence, the only certainty of which is death. In Le Bon Dieu , the chansonnier goes so far as to unite God and man:

"Mais tu n'es pas le Bon Dieu

Toi tu es beaucoup mieux

Tu es un homme"

"But you are not God

you are much better

you are human"

The focus of his chansons is always on people, their position in the world and general human issues. Carole A. Holdsworth therefore sees Brel as a representative of contemporary humanism .

Love and women

A central theme in Brel's oeuvre is love . However, Jean Clouzet claims that Brel never wrote a real love song; rather, his chansons were always about unhappy loves. Similar to the subject of faith, there is also a temporal development in Brel's chansons with love. At a young age, Brel created a highly idealized image of romantic love that seeks fulfillment in a lasting bond, for example in the chanson Heureux :

"Heureux les amants que nous sommes

Et qui demain loin l'un de l'autre

S'aimeront s'aimeront

Par-dessus les hommes."

"Happiness is: being in love like us

and: being one from another

love, being

love forever remaining love"

Chris Tinker, however, emphasizes the narcissistic perspective of many of Brel's love songs, which always focus on the feelings of the lover, while those of the loved one hardly play a role. In addition, the chansons exaggerated the subject of their love and overloaded it with moral expectations to such an extent that the disappointment seemed already predetermined. It is logical that, at the end of the 1950s, when Brel's protagonists generally lose their early idealism and lean more towards pessimism , they mourn their lost, unhappy, or unattainable love just as extensively as they previously longed for it.

The image of women that Brel drew in his later phase is cynical to the point of misogyny , as many critics have accused it of. Now mainly female characters populate the chansons that men exploit and cheat. In Les filles et les chiens , Brel asks whether women or dogs would be better companions for a man. In Les biches he compares them to hinds:

"Elles sont notre pire ennemie

Lorsqu'elles savent leur pouvoir

Mais qu'elles savent leur sursis

Les biches"

"They are our worst enemies

If they know their power

But also their reprieve

The cows"

Carole A. Holdsworth pointed out, however, that Brel's late works also contained negative drawings of male figures, and that guilt is often evenly divided between the sexes. In this sense, Brels misanthropy , which was associated with misogamy , i.e. an aversion to marriage, increased in general . Some voices see true love songs in Brel's work as those that deal with friendship between men, such as the consolation of the unfortunate Jef in the chanson of the same name. It is only in Orly , one of his last chansons, that a woman is shown as abandoned by the man who receives the chansonnier's compassion. For Anne Bauer it is “the only Brel chanson in which there is love without reservations, without ulterior motives and without lies”.

From the beginning of the 1960s onwards, Brel's chansons show several ways to overcome the disappointments of love. Some "chansons dramatiques", dramatic songs that live especially from the presentation on stage, perform a hero who in his initial dreams is more and more disillusioned with reality, but in the end regains his confidence and hopes for the future again looks. This includes the well-known chanson Madeleine , the narrator of which waits in vain for his beloved every evening and nevertheless confidently trusts her appearance on the following day. Also Les bonbons and its sequel Les bonbons 67 such "chansons dramatiques" in which a young man with sweets hopeless woos his beloved, where Brel his hero oversubscribed such that the courtship into a parodic farce turns. In the late La chanson des vieux amants , Brel finally demonstrates a mature and pragmatic approach to love relationships from the perspective of a couple who have grown old together.

Childhood, old age and death

Children and childhood itself are a common theme in Brel's chansons. Childhood is portrayed as an ideal state, full of freedom, energy, fulfilled wishes and unbroken dreams. Brel often uses the metaphor “Far West” (“ Wild West ”) for this. In the later chansons it is above all a nostalgic look that an adult throws back on the lost paradise of childhood, for example in the chanson L'enfance from the film Le Far-West :

"L'enfance

C'est encore le droit de rêver

Et le droit de rêver encore"

"Childhood

That is the right to dream, to dream

still and still"

Childhood is under constant threat from adults who, in an effort to protect them, rob their children of the carefree adventures of childhood. Again and again in his songs, Brel describes how the war, also part of the adult world, ended his own childhood in one fell swoop.

For Brel, aging is a negative and dreaded process. In L'age idiot , any age, whether it's 20, 30 or 60, is an “idiotic age”. In La chanson de Jacky the return to the lost childhood, the time when Jacques was still called “Jacky”, turns out to be impossible, in Marieke that to the time of first love. In old age, like in Les vieux, people lose their illusions, in Le prochain amour the transience of love becomes aware. The ultimate separation through death expresses the chanson Fernand :

"Dire que Fernand est mort

Dire qu'il est mort Fernand

Dire que je suis seul derrière

Dire qu'il est seul devant"

"When you think that Fernand is dead

When you think that he's dead Fernand

When you think that I'm alone back there

When you think that he's alone up there"

The second most common theme after love in Brel's chansons is death . For his chanson heroes it forms the natural end of life. In Le dernier repas you face it with self-confidence and fearlessness, in Le moribond with a final revolt of joie de vivre and hedonism . Some of Brel's chansons literally long for death, such as L'age idiot , where it is referred to as the Golden Age , Les Marquises , where it fills people with calm, and Vieillir , where sudden death is preferred to the gradual process of aging . Brel's chanson Jojo , written out of mourning for his deceased friend Jojo Pasquier, makes the loneliness of the bereaved palpable, but his enduring friendship gives the deceased a form of immortality.

critics on society

Brel's work contains numerous bitter accusations and sharp attacks against the society in which he lives. For Carole A. Holdsworth the motto of his work is the fight of the individual against his environment and the refusal to allow himself to be shaped by it. Although for Brel the problems are not primarily of an economic, but of a psychological nature, his sympathy, which he himself comes from a wealthy middle-class family, applies to the poor, the oppressed and the weak. His critical attacks are never directed against individual individuals, but rather generalize, as the specific article in many chanson titles already reveals: Les bigotes , La dame patronnesse , Les flamands , Les paumés du petit matin , Les timides , Les bourgeois .

The bourgeoisie in particular was a preferred target for Brel, as it was for many other left-wing intellectual artists of his generation. He dedicated the chanson Les bourgeois to her , the refrain of which reads:

"Les bourgeois c'est comme les cochons

Plus ça devient vieux plus ça devient bête"

"Citizens are like pigs in the barn,

because the older they are, the more dirty they are."

The song, in which a group of young people shows the citizens their bare bums, takes the turn in the last verse that it is now the old-fashioned bourgeois horror of yore who are insulted and ridiculed by a new young generation as "bourgeois". This shows that Brel's concept of the bourgeoisie is not primarily a question of social class , but rather it castigates an attitude towards life. One becomes a bourgeois in the Brelian sense when one loses one's spontaneity and curiosity and leaves to stagnation, passivity and standstill. For Brel, part of the rejected bourgeois world are also the institutions of the family , school and the Catholic Church, with their restrictions on individual freedom.

Despite his critical appraisal of society and its social injustices, Brels Chansons lacks any concrete political solution to change. In the chanson La Bastille, with the storming of the Bastille, he even questions the entire French Revolution , which was not worth the blood shed:

"Dis-le-toi désormais

Même s'il est sincère

Aucun rêve jamais

Ne mérite une guerre"

"Tell yourself from now on

that no dream

itself is not

worth a war to be taken seriously "

The people in Brel's chansons often remain in passivity and fatalism, unable to effect change. Your feeling of personal failure is paired with powerlessness in the face of social restrictions. The chansons do not go beyond an accusation of the circumstances, but encourage the listener to think critically.

Brel and Belgium

Brel's relationship with his homeland was difficult. He felt confined in Belgium, but still emphasized his Belgian origins in his adopted country of France. Olivier Todd spoke of a "love-hate relationship" which showed that Brel felt both pride and shame for his homeland. Brel, who was of Flemish descent but grew up speaking French, already had problems with the Flemish language when he was at school, and later compared it to "barking dogs".

Brel snubbed his Flemish compatriots with several of his songs . The chanson Les flamands describes the strict, joyless dance of the Flminnen as a constant in their dreary life cycle. Although characterized by tender irony, the song sparked protests and threatening letters in 1959, which still surprised Brel at the time. Seven years later, on the feast day of the Belgian dynasty in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels , he deliberately provoked in La ... la ... la ...

"J'habiterai une quelconque Belgique

Qui m'insultera tout autant que maintenant

Quand je lui chanterai Vive la République

Vivent les Belgiens merde pour les Flamingants ..."

"I will live in some Belgium that will

insult me just as much as it does now

If I sing Vive la Republique to him

. The Belgians don't give a shit about the Flemish ..."

The chanson caused a scandal in Belgium in 1966. The Flemish people's movement claimed an “affront to the honor of the Flemish people” and declared Brel a persona non grata , even the Belgian parliament debated Brel's chanson. In interviews, the chansonnier himself always emphasized the difference between the terms “flamands”, the inhabitants of Flanders , whom he did not intend to attack in their entirety, and “flamingants”, the Flemish nationalists whom he simply considered to be fascists . A year before his death, he repeated his attack with the blacksmith Les F ... again, and the reaction, from the public scandal to the question before Parliament and a judicial complaint, remained the same. In the chanson, Brel characterized the "Flamingants" as:

"Nazis durant les guerres et catholiques entre elles"

"Nazis during the wars and Catholics in the meantime"

For Chris Tinker, Brel's tirades are less specifically directed against the Flemings than they are in the tradition of his other social criticism of the bourgeoisie and nationalism . On the other hand, Brel's translations of various chansons into Flemish, including Le plat pays (Mijn vlakke land) , should be understood as a personal gesture to Flemish culture and language. By combining Flemish and Francophone verses in Marieke , the chansonnier even wrote an allegory on bilingual Belgium. Sara Poole sees a decisive influence on many of Brel's chansons such as Le plat pays in Belgian culture and the poetry of Émile Verhaeren . For Carole A. Holdsworth, this chanson of the four winds that blow over the Belgian landscape is an extremely atmospheric description of Belgium, and the recurring single-line refrain of the chanson makes it clear that, despite all the critical remarks, Brel's identification with his homeland remains unbroken:

"Le plat pays qui est le mien"

"My flat country you are my country"

Movies

According to Stéphane Hirschi, Brel's two film projects are also based on the catalog of motifs in his chansons. For example, in Franz's triangle story, Hirschi perceives the implicit presence of around 50 Brel chansons and composes some film dialogues entirely from passages of song lyrics. The medium of film simply adds a new dimension to Brel's chansons, in that the images can now be presented in concrete terms and not only suggested in the head of the listener. With the soundtrack and the background music, Brel paid particular attention to the medium from which it came. Brel himself described that he built his first film much like a chanson program, heading towards a climax every nine minutes.

For Olivier Todd, Léon, Franz's protagonist , represented one of those average existences when the Brel itself could have ended if he had stayed in Belgium. However, the film was not successful because the audience could not find the world of the chansonnier in that of the film. While his first film was realistic to the point of naturalism , Brel relied on pure fantasy in the second film, Le Far-West . But the search of a group of adults for the dreams of their childhood, the paradise they imagine in the Wild West, fails, as does Léon's search for love in Franz . Death awaits the protagonists in both films: Léon chooses suicide, the cowboy Jacques dies in a hail of bullets.

As an actor, Brel gained his first experience in 1956 with a Belgian 10-minute short film for a competition in which he himself had revised the script and played the leading role. The result, however, was poor and was never shown in cinemas. Olivier Todd compared his later ten films from 1967 to 1973 with Brel's development as a chansonnier: a period as a preacher and do-gooder under the directors André Cayatte and Marcel Carné was followed by a phase as a joker and bon vivant under Édouard Molinaro and Alain Levent . Brel dedicated himself to political cinema under Philippe Fourastié and Jean Valère , while his own directorial work reflects Brel's late pessimism . The final film The Filzlaus finally shows him as a shy dreamer. According to Todd, Brel was only convincing in those films in which the character portrayed resembled his own personality, whereby he considered the role of country doctor Benjamin to be Brel's star role. My uncle Benjamin remained the most famous of Brel's films.

reception

Significance and aftermath

Jacques Brel is one of the leading representatives of French chanson. Almost unanimously, together with Charles Trenet and Georges Brassens , he is counted among the three most important chansonniers who interpreted their own chansons, although, according to Michaela Weiss, he has achieved a more lasting effect and role model in the 21st century than his two colleagues. According to Olivier Todd, Brel was one of the ten “superstars” of French chanson as early as the 1960s, but half of them were pure interpreters. In a row with Brel, he lists Maurice Chevalier , Charles Trenet, Leo Ferré , Yves Montand , Georges Brassens, Charles Aznavour , Gilbert Bécaud , Sacha Distel and Johnny Hallyday, sorted by age . 20 years after his death, Brel's albums - especially alongside those of Édith Piafs - were still among the best-selling albums in French according to Marc Robine. In the 21st century they were still selling 250,000 copies a year, and the text edition of his works has remained permanently on offer since its first edition in 1982 with numerous new editions.

Brel has not only become an institution of French chanson, but is now one of the best-known Belgians in general - alongside Eddy Merckx , René Magritte and Georges Simenon , for example . The French journalist Danièle Janovsky even described the French-singing Flemish as a “symbol for Belgium par excellence”. On the 25th anniversary of Brel's death, the city of Brussels declared 2003 the Brel year, in which various exhibitions and events were organized around the chansonnier. In 2005, Brel took the top spot in an audience vote for the “greatest Belgian” in the Walloon edition Le plus grand Belge , and in the Flemish counterpart De Grootste Belg he came 7th.

In the Brussels district of Anderlecht , a metro station on line 5 bears the name Jacques Brel . A library, numerous cultural and leisure centers, schools, youth hostels, restaurants, squares and streets were named after the chansonnier. In August 1988, the Belgian astronomer Eric Walter Elst discovered an asteroid , which he named (3918) Brel . Since the same year there has been a statue of Jef Claerhout on the Predikherenrei in Bruges , dedicated to Brel's chanson Marieke .

The Brels work has been managed since 2006 by the Éditions Jacques Brel , an association of the music publisher Éditions musicales Pouchenel, founded in 1962, and the Fondation Brel by his daughter France, which was founded in 1981 and has been running the Éditions since then.

Brel myth

According to a study by Thomas Weick, the admiration for Jacques Brel took on the traits of a mass myth over time, to which both Brel's work and his life contributed. Brel's chansons met the needs of the young post-war generation with an uncompromising refusal of social conformity , combined with the expression of an ideal humanism. The public later found the breakout from society embodied several times in Brel's life, from the early renunciation of his family milieu, the breakdown of the chanson career at its height to the flight from civilization, whereby the chansonnier became the proxy for his audience, who wanted their urge Realized freedom and adventure as well as her search for happiness. Brel's initial rejection - especially because of his physique - led to the image of a “suffering hero” who, through overcoming his insults and rising to become a recognized star, advanced to become a positive figure of identification. On the other hand, his powerlessness over his illness and his early death appealed to compassion.

Contributing to its popularity - for example in comparison to Georges Brassens and Leo Ferré - simple and clear language as well as the themes and ideals conveyed by the chansons, in which the audience found themselves. The contradiction between Brel's life and work was largely overlooked by the contemporary audience, who reduced the chansonnier to the statements of his songs. Later, it was precisely the insoluble contradictions that led to a mystification and the survival of the myth. In Brel's reception, a particular accumulation of comparisons with other mythical figures or terms can be seen, especially since the musical L'homme de La Mancha the comparison with Don Quixote and after his move to the South Seas the emphasized commonality with Paul Gauguin and the general myth of the search for paradise.

Sara Poole particularly emphasizes the fact that Brel's work, in contrast to Georges Brassens, for example, can be imported worldwide, that his form of lecture about voice and body, music and gestures has overcome the barriers of language. Brel's empathy and addressing the audience have found a broad audience across all ages and classes of society. According to Olivier Todd, identification is particularly high among those parts of the audience who do not get off particularly well in Brel's chansons: among the women whom he repeatedly snubbed in his texts, and among the youth who he liked to give moral sermons.

Performers

Numerous artists have interpreted Brel's chansons, be it in the original French or in translations into other languages. As early as 1988 there were 270 versions of Brel's successful song Ne me quitte pas in the United States and 38 in Japan . In addition to the fundamental problem of translating songs into foreign languages, Brel's chansons are particularly difficult to interpret. For example, Thomas Weick identifies the reasons for the frequent failures of the interpretations - he cites the commercially successful version Ces gens-là by the band Ange as an example - a lack of familiarity with Brel's personality and work, as well as a lack of talent for expressing it dramatically. Bruno Hongre and Paul Lidsky go so far that no one except Brel can sing his chansons himself, because in contrast to works by other chansonniers, their staging, rhythm and flow are perfectly tailored to Brel's performance. They should be understood less as songs than as compressed, intense dramas .

The first Brel interpreter was Juliette Gréco , who performed his chanson Le diable (Ça va) at an appearance at Olympia in 1954 . After her, Serge Lama , Barbara , Isabelle Aubret and Jean-Claude Pascal took several of his songs into their repertoire in France , and numerous other singers only sang individual chansons. Liesbeth List made Brel's chansons known in Flemish, and Herman van Veen also transmitted some of his songs. In the English-speaking world, Brel introduced Mort Shuman and Eric Blau as well as Rod McKuen in particular . Its version, Seasons in the Sun , sung by Terry Jacks , became a world hit in 1974. Also, Scott Walker was successful with several Brel transmissions. Individual songs were interpreted by Tom Jones , Andy Williams , Dusty Springfield , Shirley Bassey , Daliah Lavi , David Bowie and Sting . Former English professor Arnold Johnston has translated several revues into English since 1990 and is widely recognized for his authentic translations of Brel's texts.

The first German versions were sung by the Austrian actor and chansonnier Michael Heltau , who had met Brel personally in Antwerp. The very free re-poems interpreted by Heltau came from Werner Schneyder . The adaptations of Heinz Riedel, performed by the German songwriter Klaus Hoffmann , remained closer to the original . He later translated Brel's chansons himself and dedicated the musical Brel to him in 1997 - the last performance . Other German-speaking Brel interpreters are Gottfried Schlögl , Gisela May , Konstantin Wecker and Hildegard Knef . The actor and singer Dominique Horwitz interprets Brel's chansons in the original French.

Various colleagues dedicated musical homages to Brel , such as Dalida , Pierre Perret , Mannick , Jean Roger Caussimon , Jean-Claude Pascal and Sacha Distel . Juliette Gréco put together a program from his songs on the occasion of Brel's tenth anniversary of death, Barbara drew parallels between painter and singer in her chanson Gauguin . Stéphane Hirschi lists Claude Nougaro , Bernard Lavilliers , Francis Lalanne , Jean-Jacques Goldman and Mano Solo among the large number of artists on whom Brel exerted a strong stylistic influence . Brel's nephew Bruno Brel also followed his uncle in the profession of chansonnier. In 2001 he sang a CD called Moitié Bruno, moitié Brel , which consists of half of his own songs and half of his uncle's chansons.

Works

Discography (selection)

Jacques Brel has released numerous LPs , EPs and singles , as well as compilations from previously released recordings. The selection is limited to the 15 albums of the complete edition from 2003. Since most of Brel's albums did not have a title at the time of their publication, the CD titles from 2003 are given for identification.

- 1954: Grand Jacques

- 1957: Quand on n'a que l'amour

- 1958: Au printemps

- 1959: La valse à mille temps

- 1961: Marieke

- 1962: Olympia 1961 (live)

- 1962: Les bourgeois

- 1964: Olympia 1964 (live)

- 1966: Les bonbons

- 1966: Ces gens-là

- 1967: Jacques Brel 67

- 1968: J'arrive

- 1968: L'homme de la Mancha (French version of the musical The Man of La Mancha )

- 1972: Ne me quitte pas (modernized new recordings of older chansons)

- 1977: Les Marquises (Original title: BREL )

Filmography

- 1956: La grande peur de Monsieur Clément (short film) - Director: Paul Deliens (book, actor)

- 1967: Defamation / Occupational Risk (Les risques du métier) - Director: André Cayatte (actor, music)

- 1968: La bande à Bonnot (actor, music)

- 1969: Mein Unkel Benjamin (Mon oncle Benjamin) (Actor, Music)

- 1970: Mont-Dragon - Director: Jean Valère (actor)

- 1971: Murderer according to regulations / Murderer in the name of order (Les assassins de l'ordre) - Director: Marcel Carné (actor)

- 1972: Franz (director, book, actor, music)

- 1972: The kidnappers send their regards (L'aventure c'est l'aventure) (Actor)

- 1972: A charming crook (Le Bar de la fourche) - Director: Alain Levent (actor, music)

- 1973: Die Filzlaus (L'emmerdeur) (Actor, Music)

- 1973: Le Far-West (direction, book, actor, music)

literature

Biographies

German

- Jens Rosteck : Brel - The man who was an island . Mare, Hamburg 2016. ISBN 978-3-86648-239-5

- Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 .

French

- Marc Robine: Le Roman de Jacques Brel . Carrière, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-253-15083-5 .

- Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel. Une vie . Laffont, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-221-01192-9 .

English

- Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème . Chrome Dreams, New Malden 2010, ISBN 978-1-84240-535-2 .

Text collections

German French

- Heinz Riedel: The civilized ape . Damocles, Ahrensburg 1970.

French

- Jacques Brel: Tout Brel . Laffont, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-264-03371-1 .

- Jacques Brel: œuvre intégrale . Laffont, Paris 1983, ISBN 2-221-01068-X .

- Jean Clouzet (Ed.): Jacques Brel. Choix de textes, discography, portraits . Series Poètes d'aujourd'hui 119 . Seghers, Paris 1964.

Investigations

German

- Anne Bauer: Jacques Brel: A fire without slag . In: Siegfried Schmidt-Joos (Ed.): Idole 2. Between poetry and protest. John Lennon. Van Morrison. Randy Newman. Jacques Brel . Ullstein, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-548-36503-5 , pp. 145-179.

- Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-42936-3 .

- Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment . Winter, Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-8253-1448-0 .

French

- Patrick Baton: Jacques Brel. L'imagination de l'impossible . Labor, Brussels 2003, ISBN 2-8040-1749-4 .

- Stéphane Hirschi: Jacques Brel. Chant contre silence . Nizet, Paris 1995, ISBN 2-7078-1199-8 .

- Bruno Hongre, Paul Lidsky: L'univers poétique de Jacques Brel . L'Harmattan, Paris 1998, ISBN 2-7384-6745-8 .

- Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 .

English

- Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel . Lang, Bern 1979, ISBN 3-261-04642-2 .

- Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation . University Press of America, Lanham 2004, ISBN 0-7618-2919-9 .

- Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson . Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 2005, ISBN 0-85323-758-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Jacques Brel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Jacques Brel in the SUDOC catalog (Association of French University Libraries)

- Jacques Brel in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Official website of the Éditions Jacques Brel (multilingual)

- Wolfgang Rössig: Jacques Brel, French chanson poet. ( Memento from March 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon .

- Maegie Koreen and Manfred Weiss: six feet to earth - and yet not dead. Jacques Brel 1929–1978 (pdf; 195 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème. Pp. 201, 204.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 14-15, 19.

- ↑ Eddy Przybylski: L'usine de Brel . In: La Dernière Heure of February 7, 2005.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 14, 21, 26.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Mon enfance (1967). In: Tout Brel. P. 324.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 31.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 31-35.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 50.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 52-57.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 59, 71.

- ^ Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème. Pp. 203-204.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 69-70.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Il pleut (1955). In: Tout Brel. P. 127.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 78, 82.

- ^ Marc Robine: Le Roman de Jacques Brel. P. 89.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 75, 80-81, 85.

- ↑ "J'ai débute longtemps ... pendant cing ans". After: Bruno Hongre, Paul Lidsky: L'univers poétique de Jacques Brel. P. 11.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 87-91, 98-99.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 110, 247.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 102-107.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 127-131.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: Ne me quitte pas (1959). In: Tout Brel. P. 179.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 131.

- ^ Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème. Pp. 64-66.

- ↑ Jean Clouzet (Ed.): Jacques Brel . Seghers, Paris 1964, p. 187.

- ^ To section: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 139-141, 150, 159.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 86, 188, 193.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 176, 180.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 193, 213, 217.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 249.

- ^ Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème. P. 91, 143. In Todd's biography, the two women are given the pseudonyms "Sophie" and "Marianne".

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 250-251, 287.

- ^ To section: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 268-270, 274.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: Un enfant (1965). In: Tout Brel. P. 304.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 42.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 116-119, 173-175.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 300-301.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Les vieux (1963). In: Tout Brel. P. 249.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 301.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 376, 385-390.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 390-391, 398.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 403, 422.

- ^ Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème. P. 144.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 432-436.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 437-439, 451, 454-455.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: La quete (1968). In: Tout Brel. P. 29.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 451.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 460-461.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 469-472, 488-489.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 506, 525.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 541-546.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 547-548.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 565, 570, 579.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 584, 588-590.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: L'ostendaise (1968). In: Tout Brel. P. 340.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 590.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 599-600, 602.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 615, 622, 627.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 632, 641.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 315.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: Une île (1962). In: Tout Brel. P. 228.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 654.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 657-660.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 657-660, 693.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 679-683.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 700-702.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 706-707.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 720-721.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 725-728.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 740-743.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 738-739.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 749-751.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 756-757.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 12-13, 168.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 399.

- ^ Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel. Pp. 7-8.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 12-13, 21.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 247-257.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 262-267.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. Pp. 63-74.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. Pp. 37-47.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 253-255, 258.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 168-170.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 153, 161-162.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 78, 140.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. P. 29.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 172, 174.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 172-173.

- ↑ All quotations from: Hurricane in the hall . In: Der Spiegel . No. 36 , 1967, p. 106 ( online ).

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 188-191.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 26, 260-262.

- ↑ After Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. P. 4.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 256-259, 262.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 174-180.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Grand Jacques (C'est trop facile) (1953). In: Tout Brel. P. 113.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 126.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 31-36.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Le Bon Dieu (1977). In: Tout Brel. P. 353.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 666.

- ^ Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel. Pp. 10-11, 129.

- ↑ Jean Clouzet (Ed.): Jacques Brel. Choix de textes, discography, portraits. P. 31.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Heureux (1956). In: Tout Brel. P. 139.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 172.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 56-65, 83.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: Les biches (1962). In: Tout Brel. P. 218.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 279.

- ^ Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel. Pp. 82-86, 99.

- ↑ Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur. P. 216.

- ↑ Anne Bauer: Jacques Brel: A fire without slag . P. 159.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 99-108.

- ^ Jacques Brel: L'enfance (1973). In: Tout Brel. P. 67.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 535.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. Pp. 49-62.

- ^ Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel. Pp. 66-70.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Fernand (1965). In: Tout Brel. P. 297.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 617.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 253.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 16-18, 24-29.

- ^ Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel. Pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: Les bourgeois (1962). In: Tout Brel. P. 224.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 50.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 117-129, 133-134, 140.

- ^ Jacques Brel: La Bastille (1955). In: Tout Brel. P. 129.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 117.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 163-166, 172.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 344-345, 356, 369.

- ↑ Jacques Brel: La… la… la… (1967). In: Tout Brel. P. 318.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 361.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 357-366.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Les F ... (1977). In: Tout Brel. P. 354.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 366.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson. Pp. 149-152.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. Pp. 3-7.

- ^ Carole A. Holdsworth: Modern Minstrelsy. Miguel Hernandez and Jacques Brel. Pp. 25-26, 30.

- ^ Jacques Brel: Le plat pays (1962). In: Tout Brel. P. 226.

- ↑ Translation from: Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 182.

- ↑ Stéphane Hirschi: Jacques Brel. Chant contre silence. Pp. 463-467.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 511, 525, 528-529, 544-545.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 467-472, 480.

- ^ Alan Clayson: Jacques Brel. La Vie Bohème . P. 141.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 10-16.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. Pp. 247-248.

- ^ Marc Robine: Le Roman de Jacques Brel. P. 610.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. S. xv.

- ↑ “The symbols of the Belgique”. After: Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. P. 8.

- ↑ Brel Bruxelles 2003 on idearts.be (French).

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. P. 71.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. P. 4.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. P. 102, 104. See picture on flickr .

- ↑ Presentation ( Memento of October 22, 2008 in the web archive archive.today ) on the website of the Éditions Jacques Brel, version of October 22, 2008.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 35-44, 66, 70.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 66, 69-70.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 21-22, 69.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel , p. 71.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 33, 39, 43.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation. S. xv-xvi.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life. P. 8.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 214-215, 229, 260.

- ↑ Bruno Hongre, Paul Lidsky: L'univers poétique de Jacques Brel. P. 99.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 249-251, 255-256.

- ↑ An Interview with Arnold Johnston . In: ata Source ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. No. 44, American Translators Association Newsletter , Winter 2008, pp. 8-13.

- ^ Johnston's Brel translation among Chicago's top shows , Western Michigan University News , July 9, 2008.

- ↑ Best of Brel on Michael Heltau's website .

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 251-253, 229, 260.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Pp. 191-196.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel –Chanson between poetry and commitment. Pp. 270-275.

- ↑ Stéphane Hirschi: Jacques Brel. Chant contre silence. P. 475.

- ↑ biography on the website of Bruno Brel.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Brel, Jacques |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Brel, Jacques Romain Georges (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Belgian chansonnier and actor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 8, 1929 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Schaarbeek , Belgium |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 9, 1978 |

| Place of death | Bobigny , France |