Orly (chanson)

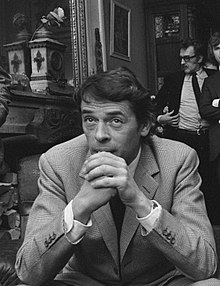

Orly is a chanson by the Belgian chansonnier Jacques Brel in French . It was recorded on September 5, 1977 and released on November 17 of the same year on Brel's last LP with Disques Barclay . The album of the chansonnier, who returned from the South Seas after a long artistic break , became a public event in France. Orly is considered one of the standout chansons on Brel's last release.

The song is about a couple in love who say goodbye to each other at Paris-Orly airport . What is unusual for Brel's oeuvre is the role of the narrator as an observer and the non-predominantly male point of view that ultimately focuses on the abandoned woman. Orly can be interpreted not only as a sad love song , but also, with its allusions to illness and death, as the terminally ill chansonnier's farewell to life. In the chorus, Brel concludes that life does not distribute gifts. By naming his colleague Gilbert Bécaud , he refers to his much more optimistic chanson Dimanche à Orly about wanderlust at the airport.

Text and music

Sundays in Orly : Over two thousand people stream through the airport, but the narrator only has eyes for two, a pair of lovers who stand in the rain and hug each other so tightly that their bodies melt together. They tearfully affirm their love, but do not make promises to one another that they cannot keep. Finally their bodies separate very slowly, holding each other again until the man suddenly turns away and is swallowed up by a staircase. The woman is left with her mouth open, suddenly aged, as if she had met her death. She's lost men in the past, but this time it's love that she's lost. She feels fragile, as if she was meant to be sold. The narrator tries to follow her, but then she too is swallowed up by the crowd.

The refrain is:

"La vie ne fait pas de cadeau

Et nom de Dieu c'est triste

Orly le dimanche

Avec ou sans Bécaud"

Which can be translated as: “Life doesn't give gifts. And in God's name (also stronger: damn it), it's sad on Sundays in Orly, with or without Bécaud. "

The verses take some liberty with regard to rhyming , but strictly follow the meter of half Alexandrians . The melody is extremely monotonous. It begins with changing two simple chords on a gently struck guitar, which, according to Hubert Thébault, creates the effect of a heartbeat. It is the tonic and dominant seventh chord in C minor for the first and third quarter notes of a three-quarter time . While Brel accompanies himself through the first verse alone , the orchestra, led by his long-time arranger François Rauber , only begins explosively after the first chorus . The four accentuated inserts act “like an acoustic exclamation mark”. From the second stanza onwards, the strings set the rhythm, while the winds in the third stanza support the crescendo characteristic of Brel . Ulf Kubanke speaks of a “blown echoing echo of the wind”, Hubert Thébault reminds the trumpet fanfares of a corrida . As was typical for the collaboration between Brel and Rauber, Brel had precise ideas about the musical style and instrumentation, including the trumpet part, from the start, but then Rauber had the details worked out.

Background and history

In May 1967, at the age of just 38, Brel gave his farewell performance as a chansonnier on stage. In the following year, a last long-playing record was released, after which Brel only appeared in a musical and various films. In November 1974, the singer , who had lung cancer, had to undergo an operation that removed part of his lungs. In December of that year he set out with his lover Maddly Bamy to cross the Atlantic by sailing ship. A few weeks earlier he had said goodbye to another lover named Monique whom he never saw again. Eddy Przybylski suspects this separation at an airport (not in Orly, but with the Paris airport as the travel destination) as the biographical background of the Orly chanson . Brel's journey took him through several stops to the Marquesas Islands, where he settled permanently on Hiva Oa in June 1976 . On the island where Paul Gauguin had already spent his last years, Brel found the inspiration for 17 new chansons about "a few things that have been going through my head for fifteen years".

In August 1977, Brel surprised his old companions with a short-term return to Paris. He hid in a small hotel near the Place de l'Étoile from the French public, where rumors about the terminally ill chansonnier were circulating . In his luggage he had a cassette with test recordings of his new chansons. Gérard Jouannest criticized the monotony of the melodies, but François Rauber decorated them with his arrangements. Eddie Barclay had rented a studio on Avenue Hoche for the recordings . Brel recorded the songs together with an orchestra led by Rauber, but never more than two chansons per working session, which had to be completed in a few takes. Brel's voice had weakened, he could only sing for three hours straight before he had to take a break. He tried to loosen up the tense atmosphere in the fully occupied studio with jokes about his missing lungs. Orly and Jojo were among the first two chansons that Brel recorded on September 5th.

When Brel's last record was released on November 17, 1977, it generated tremendous public interest. The record had no title, the cover only showed the four letters of his last name against a blue cloudy sky. Barclay did not advertise conventionally, but with demonstrative secrecy, the delivery of locked containers and the opening of the combination locks at the same time, provided a special advertising coup that made expectations skyrocket and 1 million pre-orders. Brel, who had already left Paris for the South Pacific, was annoyed by the hype. He lived in Hiva Oa for a good six months, until his health deteriorated so much that he had to return to Paris again in July 1978, this time for chemotherapy . Three months later, he died of heart failure on October 9, 1978 in Bobigny near Paris.

interpretation

Love and separation

According to Maddly Bamy, Brel described Orly as "une belle chanson d'amour" ("a beautiful love song "). For Sara Poole, it is in line with chansons like Ne me quitte pas or Madeleine , which powerfully and dramatically evoke despair and being at the mercy of deep passions. Monique Watrin reminds the “mini tragedy ” Orly of the early, passionate Brel from 1959, the year in which he wrote the “love song of the century” (according to Frédéric Brun) with Ne me quitte pas . From the point of view of his chanson colleague Serge Lama , Brel wrote only four real love songs: Ne me quitte pas , La chanson des vieux amants , Orly and Jojo . For Anne Bauer, Orly is “the only Brel chanson in which there is love without reservations, without ulterior motives and without lies”.

Orly describes the painful separation of a couple who love each other but cannot stay together because of unsuccessful circumstances. Unlike in chansons like Je ne sais pas (1958) or La Colombe (1959), the separation does not take place on a platform, but in the midst of the crowd at a busy airport. And also unlike in previous chansons, Brel stays completely out of the action and limits himself to describing what he sees. He uses quasi-cinematic stylistic devices and alternately directs the lens at the couple as a whole and the individual persons, their behavior, their gestures, their looks and their tears, with which he paints a disaffected picture of human existence. The introductory lines “Ils sont plus de deux mille / Et je ne vois qu'eux deux” (“They are over two thousand and I only see them both”), which are repeated twice in the course of the first two stanzas, serve as a kind of leitmotif . They serve to focus , direct the narrator's gaze from the general to the particular.

At the beginning Brel shows the couple as a unit with expressions such as "eux deux", "ces deux", "tous les deux" and "ils" ("they both", "these two" "both" and "they"). It evokes in the listener the image of a very close, intimate union. This is reinforced by the external circumstances, the rain that envelops both and is reflected in their tears, as well as the common fire that burns in both. In the first, reluctant attempts at separation, the related movement of the two bodies is reminiscent of natural elements, of ebb and flow. The couple stand out from the crowd, not only through the focus of the viewer, but also by living a love that is incomprehensible to the other, is condemned by them. It is a love that knows about its limitations, that does not need false promises and that grows through the obstacle between lovers.

With the separation of the couple, the individual beings emerge. Both cope with the pain in their own way, which transports typical gender roles for Watrin . First the man becomes recognizable as an independent person. Here Brel works with a Syllepse , in which it is only corrected in retrospect that it was the man alone who cries out his pain in “gros bouillons” (“thick broth”). This combination of the idioms “bouillir à gros bouillons” (“cook quickly”) and “pleurer à chaudes larmes” (“cry your eyes”), for Sara Poole, associates thick tears, desperate, uncontrolled sobs and passionate, feverish heat . The man is also the first to endure the suffering, neither his own nor that of the partner. He flees in activity and brusquely carries out the separation that has previously been postponed.

The woman stays behind. As before with the man's tears, Brel also uses hyperbole in her pain , a stylistic device of exaggeration and, according to Patrick Baton, a veritable explosion of time: "Ses bras vont jusqu'à terre / Ça y est elle a mille ans" ("Your Arms go to the ground / The time has come, she is a thousand years old ”). According to Hubert Thébault, the farewells to lovers in Brel's chansons have always been as heartbreaking and final as death. After the loss of love, the woman thinks she will encounter her own death. The connection between love and death is followed by a symbolic circle as it revolves around itself. She refuses to acknowledge reality and imagines impossible happiness to sustain her life. In the end she feels “à vendre” (“for sale”), because Brel's chanson characters believe even less in eternal loyalty than in eternal love. For Watrin, however, the vocabulary also offers the possibility of a life without others, the opening of a new dimension in one's own future.

Sara Poole says there are no winners in the couple's breakup. Both suffer equally. What is unusual about Orly , however, is that for the first time in Brel's oeuvre it is not the man but the woman who are depicted as abandoned, as victims, given the compassion and pity of the chansonnier. Poole finds the portrayal of the abandoned far more touching than, say, the admirer waiting in vain with his bouquet in Madeleine . Like Michaela Weiss, she opposes the empathy of this chanson to the frequently voiced accusation of misogyny in Brels chansons such as Les biches . Marc Robine asked regarding this allegation: "mais comment peut-on encore y croire après avoir Ecoute Orly ?" ( "How can it still believe after Orly has heard?") For Bruno Hongre and Paul Lidsky it is the last message Brels, according to the exclusively male perspective of his chansons, to have recreated the broken heart of a woman with such intensity in the end.

Sickness and death

In 1978, in a conversation with his friend, the physician Paul-Robert Thomas, Brel himself pointed out a different, more personal reading of the chanson:

«As-tu écouté ma chanson Orly avec attention? Il s'agit de deux amants qui se séparent, mais surtout d'une métaphore de la Vie et de la Mort. D'un être qui sent sa vie lui échapper; le jour où, by example, il décide de partir se faire soigner. Et l'avion se pose à Orly! Dernier aéroport, pour un dernier voyage… »

“Have you listened carefully to my chanson Orly ? It is about two lovers who split up, but especially a metaphor about life and death. One who feels that his life is fleeing from him; the day, for example, when he decides to leave for treatment. And the plane lands in Orly! Last airport for one last trip ... "

According to Sara Poole, the petrified woman, left behind, faces a future from which meaning and life have given way after the man has been "swallowed" by the stairs ("Bouffé"). For Brel's daughter France and André Sallée it is a staircase into the darkness that devours the man as if he were being consumed by an illness. Jean-Luc Pétry also recognizes this illness in the comparison of the couple with the surrounding crowd: the lean bodies of lovers are in the midst of healthy, well-nourished air travelers who become voyeurs of their pain. The narrator, with terms like “adipeux en sueur” (“sweating fats”) or “bouffeurs d'espoir” (“bearer of hope”, literally: “hope eater”), literally accuses them of the good constitution of the bystanders, because their health is so indecent the suffering couple.

Sébastien Ministru continues in his interpretation for the RTBF : "L'escalier, c'est la mort." ("The stairs, that is death.") There is explicit mention of the disappearance of the man, all in one Vocabulary that does not come from a departure hall, but from a dying room: dry bodies, drooling words, grief, tears, a scream, a restless hand like a last outbreak of life. In all of this lies the description of a death throes, the last breath of a dying person. It is a farewell greeting from the terminally ill Brel, who died eleven months after the release of his last album.

With or without Bécaud

In Orly's chorus , Brel refers to a famous song by his chanson colleague Gilbert Bécaud from 1963: Dimanche à Orly . Its text comes from Pierre Delanoë , the music from Bécaud. It is about the hopeful fantasies of a little employee who goes to Paris-Orly airport every Sunday to watch the planes and dream of distant lands. One day, he hopes, he will be in such an airplane himself. The refrain begins with the verses:

«Je m'en vais l 'dimanche à Orly.

Sur l'aéroport, on voit s'envoler

Des avions pour tous les pays.

Pour l'après-midi… J'ai de quoi rêver. »

The translation goes something like: “I'm going to Orly on Sunday. At the airport you can see planes flying to all countries. For the afternoon ... I have something to dream about. "

Bécaud's song, written fourteen years before Brels Orly , tells of a time when the airport was France's biggest visitor attraction even before the Eiffel Tower . After the inauguration of the Orly South Terminal in 1961, as many as 10,000 travelers came every day to spend the day in restaurants, cinemas, shopping malls and on three visitor terraces. The airport, a “huge monument made of glass and steel” (“vaste monument de glaces et d'acier”) stood for modernity and sophistication, as one could sometimes catch a glimpse of the traveling stars. Physicist Jeremy Bernstein sums up the romanticizing mood of Dimanche à Orly : “The cheer is relentless.” (“The cheering is merciless.”) And he adds that this must have got on Brel's nerves.

According to André Gaulin, Brels Orly is a real “anti-version” of Bécaud's predecessor. Chris Tinker explains that life can be cruel and tragic even when the cheerful chansons of Brel's contemporaries trickle out of the loudspeaker. Bécaud was not exactly honored to be mentioned by Brel. Claude Lemesle ruled that it was an "unnecessary allusion" ("l'inutile allusion") to the colleague, for which Brel later apologized by phone. The Dutch journalist Pieter Steinz, on the other hand, just appreciated the comic relief , the comical relief with which Orly's melancholy is relativized by a “funny musical reference” to the chansonnier colleague.

reception

While Brel's last long-playing record received a wide range of very different reviews in French criticism (from negative to very positive), the chanson Orly was often positively singled out from the overall work. For example, Jacques Marquis criticized the declining lyrics and outdated music in Télérama , but classified Orly under “trois ou quatre beaux titres” (“three or four beautiful titles”) on the record. Danièle Heymann found words of praise for Brel's publication in L'Express , but gave Orly special praise as “la plus belle chanson de rupture depuis Les Feuilles mortes ” (“the most beautiful chanson about separation since Les Feuilles mortes ”). Looking back, Ulf Kubanke thought Orly was the “highlight of the album” in his review in laut.de. And Gilles Verlant called Orly, together with La ville s'endormait and Les marquises, “trois des plus belles chansons jamais écrites par Brel” (“three of the most beautiful chansons Brel has ever written”).

Brel's older brother Pierre Brel saw Orly as the most impressive chanson from his younger brother's entire repertoire. Claude Lemesle called it “chef-d'œuvre” (“masterpiece”). Jérôme Pintoux said: “Une chanson mélo, pathétique. Un peu trop longue peut-être. ”(“ A melodramatic, pathetic chanson. A little too long maybe. ”) Pieter Steinz wrote in 1996:“ Het is het droevigste afscheidslied dat ik ken. ”(“ It is the saddest farewell song that I know. ”) This is how Steinz , who had ALS, chose the song in 2015, a year before his death, as background music for his own funeral service.

Orly has been recorded on phonograms in more than 30 cover versions . This includes translations into Afrikaans, English, Italian, Dutch and Russian. Loek Huisman translated the song into German under the title Flugplatz . Michael Heltau sang the version on the album Heltau - Brel Vol 2 in 1989 . The French original was interpreted by Dominique Horwitz (1997 on Singt Jacques Brel and 2012 on Best of Live - Jacques Brel ), Vadim Piankov (1998 on Chante Jacques Brel , 2001 on Brel ... Barbara and 2009 on Vadim Piankov interprète Jacques Brel ) , Anne Sylvestre (2000 on Souvenirs de France ), Pierre Bachelet (2003 on Tu ne nous quittes pas ), Florent Pagny (2007 on Pagny chante Brel and 2008 on De part et d'autre ), Laurence Revey (2008 on Laurence Revey ) and Maurane (2018 on Brel ).

literature

- Jacques Brel: Tout Brel . Laffont, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-264-03371-1 , pp. 355-357 (copy of the text).

- Jean-Luc Pétry: Jacques Brel. Texts and Chansons . Ellipses, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-7298-1169-9 , pp. 60-67.

- Hubert Thébault: Orly . In: Christian-Louis Eclimont (Ed.): 1000 Chansons françaises de 1920 à nos jours. Flammarion, Paris 2012, ISBN 978-2-0812-5078-9 , pp. 547-548.

- Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , pp. 212-216.

Web links

- "Orly", les adieux de Jacques Brel à la vie ... on RTBF on November 30, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jacques Brel: Tout Brel . Laffont, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-264-03371-1 , pp. 355-357.

- ↑ a b c d Hubert Thébault: Orly . In: Christian-Louis Eclimont (Ed.): 1000 Chansons françaises de 1920 à nos jours. Flammarion, Paris 2012, ISBN 978-2-0812-5078-9 , p. 548.

- ↑ See the arrangement for choir by Martin Le Ray, excerpts from La Boite à Chansons

- ^ A b Marc Robine: Le Roman de Jacques Brel . Carrière, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-253-15083-5 , p. 542.

- ↑ a b c Ulf Kubanke: Late masterpiece, shortly before his death . Criticism Les Marquises at laut.de .

- ↑ Fred Hidalgo: Jacques Brel. L'aventure commence à l'aurore. Archipoche, Paris 2014, ISBN 978-2-35287-693-9 , without pages.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , p. 422.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , p. 627.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , p. 632.

- ^ A b Eddy Przybylski: Brel. La valse à mille rêves . L'Archipel, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-8098-1113-1 , without pages.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , p. 660.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , p. 702.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , pp. 706-710.

- ^ Marc Robine: Le Roman de Jacques Brel . Carrière, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-253-15083-5 , p. 647.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , pp. 719-721.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , pp. 738-739.

- ↑ Olivier Todd: Jacques Brel - a life . Achilla-Presse, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-928398-23-7 , p. 751.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation . University Press of America, Lanham 2004, ISBN 0-7618-2919-9 , p. 27. With reference to: Maddly Bamy : Tu leur diras… Fixot, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-221-09001-2 , p. 181.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation . University Press of America, Lanham 2004, ISBN 0-7618-2919-9 , p. 32.

- ↑ a b Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , p. 212.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-42936-3 , p. 230.

- ↑ Anne Bauer: Jacques Brel: A fire without slag . In: Siegfried Schmidt-Joos (Ed.): Idole 2. Between poetry and protest. John Lennon. Van Morrison. Randy Newman. Jacques Brel . Ullstein, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-548-36503-5 , p. 159.

- ^ Jean-Luc Pétry: Jacques Brel. Texts and Chansons . Ellipses, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-7298-1169-9 , p. 64.

- ↑ Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , pp. 212-214.

- ↑ Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , p. 214.

- ↑ Patrick Baton: Jacques Brel. L'imagination de l'impossible. Labor, Brussels 2003, ISBN 2-8040-1749-4 , p. 123.

- ^ Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation . University Press of America, Lanham 2004, ISBN 0-7618-2919-9 , p. 15.

- ↑ Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , pp. 214-215.

- ↑ Patrick Baton: Jacques Brel. L'imagination de l'impossible. Labor, Brussels 2003, ISBN 2-8040-1749-4 , p. 95.

- ↑ Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , pp. 215-216.

- ^ A b c Sara Poole: Brel and Chanson. A Critical Appreciation . University Press of America, Lanham 2004, ISBN 0-7618-2919-9 , p. 27.

- ↑ Monique Watrin: Brel. La quete du bonheur . Sévigny, Clamart 1990, ISBN 2-907763-10-5 , p. 216.

- ↑ Michaela Weiss: The authentic three-minute work of art. Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel - Chanson between poetry and commitment. Winter, Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-8253-1448-0 , pp. 194-195.

- ^ Marc Robine: Le Roman de Jacques Brel. Carrière, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-253-15083-5 , p. 546.

- ↑ Bruno Hongre, Paul Lidsky: L'univers poétique de Jacques Brel . L'Harmattan, Paris 1998, ISBN 2-7384-6745-8 , p. 60.

- ^ Paul-Robert Thomas: Jacques Brel. Do'attends la nuit. Le Cherche midi, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-86274-842-0 , p. 151. See also: Fred Hidalgo: Jacques Brel. L'aventure commence à l'aurore. Archipoche, Paris 2014, ISBN 978-2-35287-693-9 , chap. 22, without pages.

- ↑ France Brel, André Sallee: Brel . Éditions Solar, Paris 1988, ISBN 2-263-01285-0 , p. 163. After: Jean-Luc Pétry: Jacques Brel. Texts and Chansons . Ellipses, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-7298-1169-9 , p. 63.

- ^ Jean-Luc Pétry: Jacques Brel. Texts and Chansons . Ellipses, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-7298-1169-9 , p. 66.

- ↑ a b c "Orly", les adieux de Jacques Brel à la vie ... on RTBF on November 30, 2017.

- ↑ Dimanche à Orly . On the Pierre Delanoë website .

- ↑ Cinquante ans après, Orly continue à faire rêver le dimanche . In: Le Parisien of March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Jeremy Bernstein : The Crooner and the Physicist . In: The American Scholar, December 1, 2004.

- ^ André Gaulin: La chanson, songeuse et voyageuse. In: L'Action nationale LXXXI, No. 6, June 1991, p. 817.

- ↑ Chris Tinker: Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. Personal and Social Narratives in Post-War Chanson . Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 2005, ISBN 0-85323-758-1 , p. 108.

- ^ A b Claude Lemesle : Plume de stars. 3000 chansons et quelques autres. L'Archipel, Paris 2009, ISBN 978-2-8098-0138-5 , without pages.

- ↑ a b Pieter Steinz: The script for my death . In: The sense of reading . Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-961139-6 , without pages.

- ↑ Thomas Weick: The reception of the work of Jacques Brel . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-42936-3 , p. 119.

- ↑ Gilles Verlant: L'encyclopédie de la chanson française. Des années 40 à nos jours. Ed. Hors Collection, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-258-04635-1 , p. 49.

- ↑ Mohamed El-Fers: Jacques Brel . Lulu.com 2013, ISBN 978-1-4478-8345-6 , p. 133.

- ↑ Jérôme Pintoux: Les chanteurs français des années 60. Du côté de chez les yéyés et sur la Rive Gauche. Camion Blanc, Rosières-en-Haye 2015, ISBN 978-2-35779-778-9 , p. 64.

- ↑ Pieter Steinz: Jacques Brel 1929-1978; In deze one reads ze een rande . In: NRC Handelsblad, October 9, 1996.

- ↑ Covers by Song on Brelitude.net.