Georges Simenon

Georges Joseph Christian Simenon (born February 12, 1903 in Liège , † September 4, 1989 in Lausanne ) was a Belgian writer . He was best known as the author of a total of 75 crime novels about the character of the Commissioner Maigret . In addition, Simenon wrote over 100 other novels and 150 short stories under his name as well as almost 200 penny novels and more than 1000 short stories under various pseudonyms . He wrote in French and used mainly the pseudonym Georges Sim under his own name until he was successful .

Simenon began his writing career at the age of sixteen as a journalist in his hometown of Liège. In the 1920s he became an extremely prolific writer of trivial literature in Paris . The novels about the character Maigret were the first works that Simenon published under his own name in the 1930s and led to his literary breakthrough. From then on, Simenon created an extensive body of detective and psychological novels that made him one of the most translated and widely read writers of the 20th century. Despite its great commercial success and numerous enthusiastic individual voices, literary criticism was inconclusive in its classification. Even with the higher literary ambitions of his "Non-Maigret" novels, he did not overcome the reputation of a crime writer and prolific writer.

Simenon's writing style is characterized by a high level of clarity and a dense atmosphere , despite the low vocabulary and the lack of any literary finesse. According to his own statement, his work is about the "naked person", the person who emerges from behind all masks. Simenon's own life story was incorporated into both the fictional works and several autobiographies . His private life was unsteady and the two marriages were accompanied by numerous affairs. Frequently traveling, he had 33 different residences in Belgium , France , Canada , the USA and Switzerland in the course of his life .

Life

Childhood and youth

Georges Simenon was born in Liege on the night of February 12th to 13th, 1903, according to the official birth certificate on February 12th at 11:30 p.m. According to Simenon's own testimony, however, the delivery did not take place until Friday, February 13 at 12:10 a.m., and his father had backdated the birth at the registry office at the insistence of the superstitious mother. This version has been adopted from most of the biographies.

Georges' father Désiré Simenon was an accountant for an insurance company, his mother Henriette Brüll had worked as an assistant saleswoman in the Liege branch of the A l'ínnovation department store before he was born. Simenon later often emphasized the contrast between the origins of his parents. The Simenons were a long-established Liège clan of farmers and workers with strong family ties. Despite their Flemish roots, they had a distinct Walloon self-image. Henriette, on the other hand, was the youngest daughter of a Prussian and a Dutch woman and was considered a foreigner in Belgium. After the ruin and early death of her father, Henriette's childhood was marked by poverty and her mother's struggle for a living. Simenon described: “My father lacked nothing, my mother lacked everything. That was the difference between them ”.

While the adolescent Georges idealized the calm and frugal father and, according to his own statements, later borrowed Maigret's character traits, the mother was always worried and, according to Simenon, found "the misfortune where no one else would have suspected it". After the birth of his brother Christian, who was three years younger than him, Georges felt put back by her; the relationship between the siblings was not very close. Simenon hardly mentioned his brother in the later autobiographical writings. Christian died in the Indochina War in 1947 after the former supporter of fascist Rexism went into hiding in the Foreign Legion on the advice of his brother at the end of the war . The difficult relationship with her mother permeated Simenon's life and work. Based on Balzac , he defined a writer as a "man who doesn't like his mother". The Lettre à ma mère (letter to my mother) written after her death became one of the final accounts .

Georges learned to read and write in kindergarten, which he attended since Christian was born. From 1908 to 1914 he attended the primary school of the Catholic Institute Saint-André. By the time he graduated, he was top of the class and favorite student of the school brothers . The altar boy felt called to the priesthood and received a half-scholarship from 1914 at the Jesuit college in Saint-Louis. But above all, he became an avid reader. The often Eastern European lodgers whom his mother had housed since 1911 introduced him to Russian literature . His favorite author was Gogol , followed by Dostoevsky , Chekhov and Joseph Conrad . He borrowed up to ten books a week from the public library, read Balzac, Dumas , Stendhal , Flaubert and Chateaubriand , Cooper , Scott , Dickens , Stevenson and Shakespeare .

The summer vacation of 1915 was a turning point in Simenon's life. The twelve-year-old had his first sexual experience with a girl three years older than him. In order to stay close to her, he switched to the Jesuit college of Saint-Servais, where he also received a half-scholarship from September 1915. Although it soon became apparent that his lover already had an older boyfriend, the change of school had an impact. Simenon lost his interest in religion, his achievements in the more science-oriented school declined. There he felt like an outsider and a prisoner. In his desire for freedom, he hung around late into the night, arguing with his mother, committing minor thefts and learning about two things that would have a big impact on his life: alcohol and prostitutes. Simenon's first attempts at writing were made at this time, using the pseudonym that accompanied him until the 1930s: Georges Sim.

The end of this phase of growing family and school problems marked a heart attack by Désiré Simenon on June 20, 1918. The diagnosis was angina pectoris and the father was predicted to have a life expectancy of a few years. It was Georges' turn to grow into the role of breadwinner at the age of fifteen. He finished school on the spot without completing the current school year and the upcoming exams. In the autobiographical novel Zum Roten Esel he described his feelings through the hero: “It was really a liberation! His father saved him. "

Journalist in Liège

Simenon's first jobs didn't last long. He broke off an apprenticeship as a pastry chef after just 14 days. As an assistant salesman in a bookstore, he was fired after six weeks because he had contradicted the owner in front of customers. Shortly before Simenon's 16th birthday, it was a last-minute decision that set the course for his future. While strolling aimlessly through Liège, he became aware of the editorial offices of the Gazette de Liège , entered, applied and was accepted. The editor-in-chief Joseph Demarteau recognized his talent and promoted him despite occasional escapades. Simenon described in an interview: “A minute ago I was just a schoolboy. I stepped over a threshold [...] and suddenly the world was mine. "

The new journalist kept the pseudonym Georges Sim. He gave and dressed with raincoat and pipe like his role model, the young reporter Rouletabille from Gaston Leroux 's crime stories . After taking over the accidents and crimes section , Simenon soon received his own column in which he was named “M. le Coq ”reported in an ironic tone by Hors du Poulailler (Outside the Chicken Coop) . The orientation of the Gazette was right-wing conservative and Catholic, without the politically indifferent Georges attaching great importance to it. He also wrote a series on The Jewish Danger , but later distanced himself from the anti-Semitic articles that were assigned to him. The biographer Stanley G. Eskin pointed out that some anti-Semitic currents flowed into Simenon's early work, but later works were free from such tendencies and Simenon was praised for the empathetic portrayal of Jews.

Encouraged by the success of his column, which appeared daily in 1920, Simenon turned to humorous literature. He published short stories in the Gazette and several other magazines, and wrote his first novel, Pont des Arches , which was published in February 1921 after Simenon had attracted 300 subscribers . Despite his professional success, Simenon saw himself as an enfant terrible of the editors, a nonconformist and a rebel. He was drawn into artistic circles and in June 1919 he joined the Liège artist and anarchist group La Caque around the painter Luc Lafnet . Here he met Régine Renchon on New Year's Eve 1920. The personality of the three years older art student impressed Simenon, although he later claimed that he had never really been in love with Tigy - so he changed her name because he did not like Régine - but above all that he longed for a partnership. The couple soon got engaged and planned a life together in Paris .

Désiré Simenon died on November 28, 1921. Georges Simenon wrote: “Nobody ever understood what was going on between father and son.” Even decades later, he confessed that he had thought of his father almost every day since then. He did his military service from December 5th. After a month in occupied Aachen , his request to be transferred back to Liège was granted, where Simenon could continue to work for the Gazette during the day . His military service ended on December 4, 1922, and ten days later he was already on the night train to Paris.

Trivial writer in Paris

Simenon's first few months in Paris were disappointing. Without Tigy, who was left behind in Liège, he felt lonely in the big wintry city. The writer Binet-Valmer , from whom he had expected an introduction to the Parisian literary scene, turned out to be a member of the Action française of dubious reputation. Instead of the hoped-for employment as private secretary, Simenon acted as an errand boy for Binet-Valmer's right-wing extremist political organization. After all, he got to know the editorial offices of the Parisian newspapers while distributing leaflets. Simenon returned to Liege to marry Tigy on March 24, 1923. He then found the desired job as a private secretary to the Marquis Raymond de Tracy, who became a father figure for Simenon. Until March 1924, his main task was to travel all over France to the property of the wealthy aristocrat.

Simenon resigned when he managed to gain a foothold in the Parisian literary scene. From the winter of 1922/23 on, he wrote so-called “contes galants”, short, erotic stories for frivolous Parisian journals. At times he published in 14 different magazines and used a variety of pseudonyms to distinguish them. For more sophisticated literature, he chose the high-circulation newspaper Le Matin . Here an encounter with the literary editor Colette was groundbreaking for the concise style of Simenon's later works. She rejected his work several times and demanded: "Delete everything that is literary". Only when he followed the recommendation and found his characteristically simple style did Colette accept the lyrics of her "petit Sim". After 25 stories in 1923, Simenon published between 200 and 300 stories in various magazines between 1924 and 1926.

Simenon made his first attempts with longer literary texts in the field of trivial literature . In 1924 he wrote his first dime novel Le Roman d'une dactylo . The title of a shorthand typist's novel already dictated the market for small employees and housewives to which Simenon tailored his texts: “romans à faire pleurer Margot” (novels that make Margot weep). Simenon did not stay with the sentimental romance novels , but covered two other main genres of the "roman populaire" with adventure novels and detective novels . He also extended his already established funny and erotic stories to the length of a novel. Despite the commercial success, Simenon understood his trivial literature, which he created under a pseudonym, primarily as an apprenticeship in the craft of writing. His talent for self-promotion led to a cover story about his high pace of work in the Paris Soir . Another event became famous without ever having taken place: Simenon was supposed to write a serial novel in a public glass cage. The plan was smashed in 1927 by the bankruptcy of the newspaper involved, but nonetheless became a popular legend that was firmly established in the minds of many as an actual event.

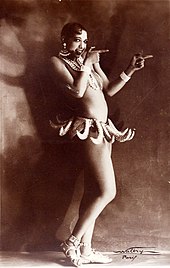

For nearly seven years from 1924 onwards, the Simenons' home was an apartment in house number 21 on Place des Vosges , a former Hôtel particulier Cardinal Richelieu . The writer now earned well, but also spent the money with full hands: on parties, trips, cars and women. Tigy, who established herself as an artist in the Parisian years, only found out about her husband's numerous affairs in 1944, when she caught him red-handed. Two women in particular became more important to Simenon at the time: Henriette Liberges was the 18-year-old daughter of a fisherman from Bénouville when Simenon and Tigy met her in the summer of 1925 on a vacation in Normandy . Simenon renamed her “Boule”, she was hired as a housemaid, soon became the lover of her “petit Monsieur” and was to remain by his side for almost forty years. The second wife was Josephine Baker , already a world star at the time, for whom Simenon acted as secretary and lover at the same time in 1927. He was so taken with her that he thought of marriage, but he feared "becoming known as Monsieur Josephine Baker". When Simenon left Paris for Île-d'Aix in the summer of 1927 , it was also an escape from the relationship with Josephine Baker.

The invention of Maigret

Although he continued to live in Paris through the winter months, Simenon had grown tired of the superficialities and distractions of the big city. In the spring of 1928 he bought a boat, which he named "Ginette", and on which he cruised through the rivers and canals of France for six months with Tigy and Boule. On board Simenon found the peace and quiet to concentrate fully on his work. In 1928 he succeeded in publishing 44 dime novels, which almost reached the entire production of 51 novels in the four previous years. In 1929 Simenon repeated the successful combination of travel and writing. He bought a larger fishing trawler that was also seaworthy and named it Ostrogoth . The voyage began in spring 1929 and led via Belgium and the Netherlands to the Baltic Sea . In that year Simenon published 34 novels and felt ripe for a literary step forward. The leap to serious literature still seemed too big for him; in his own words, he needed a "safety net". So he created "semi-literary" detective novels, the focus of which was the character Maigret .

According to Simenon's version, he invented Maigret in the winter of 1929/30 in a café in Delfzijl , the Netherlands , where the outlines of the bulky commissioner suddenly appeared in his imagination. He then wrote the first Maigret novel Pietr-le-Letton . In fact, the Simenon research later deciphered that Maigret had already appeared in four previous trivial novels of different sizes, one of which was written in Delfzijl, but in September 1929. The first real Maigret novel Pietr-le-Letton , on the other hand, was on spring or Dated summer 1930 in Paris. In any case, Simenon's publisher Fayard was by no means enthusiastic about the change in style of his lucrative trivial writer, and Simenon had to fight hard for the Maigret series and his chance of further literary development. The fact that he wanted to publish under his real name for the first time also turned out to be difficult, because everyone only knew the author as Georges Sim. To make himself known, Simenon staged a big ball on February 20, 1931, at which the invited guests were invited Criminals or police officers were in costumes, and signed the first two published novels: M. Gallet décédé and Le pendu de Saint-Pholien . The publicity was successful and the ball became the talk of the town for days.

The Maigret novels were an immediate success and instantly made Simenon famous. The press received it very positively, and translations into various languages soon followed. In the autumn of 1931 Jean Renoir pursued the traveling Simenon downright in order to acquire the film rights for La nuit du carrefour , two further film adaptations followed. Nevertheless, Simenon let the series expire after 19 novels. The novel planned as a conclusion had the simple title Maigret and put his hero into retirement. From the summer of 1932 onwards, Simenon turned to literature that three years earlier he hadn't dared to write: he wrote his first “romans durs” (hard novels). In these novels, too, a crime usually takes place, but they are not detective novels in the classic sense. Eskin referred to them as "reverse detective novels," in which the crime often does not start at the beginning, but at the end and the focus is not on the police investigation. When Simenon informed his publisher Fayard of the renewed change of course, the latter reluctantly and tried to put pressure on further dime novels with contractual obligations. Simenon then moved to the renowned publishing house Gallimard , with whom he signed a lucrative contract for six book publications a year.

In April 1932 Simenon had left Paris for good and moved to the La Rochelle area . He leased the La Richardière estate . When the lease expired in 1934, he moved near Orléans , in 1935 to Neuilly-sur-Seine , before returning to Nieul-sur-Mer near La Rochelle in 1938 . In addition to the frequent moves - in the course of his life Simenon had 33 different residences - the years were marked by long journeys on which he wrote reports : 1932 to Africa , 1933 to Eastern Europe , in 1935 an eight-month trip around the world to Tahiti and back. Marc Simenon was born on April 19, 1939 , Georges' first and Tigy's only child. Marc later became a director and also filmed his father's novels. A year and a half earlier, Simenon had announced: “I've written 349 novels, but none of that counts. I have not yet started the work that is really close to my heart […] When I am forty I will publish my first real novel, and when I am forty-five I will have received the Nobel Prize ”.

Second World War

After the German attack on the Netherlands in World War II on May 10, 1940, Simenon was drafted into the Belgian army like all reservists in his home country . When he answered, the embassy already had other plans for him. Since the invasion of German troops, numerous refugee convoys have been on their way from Belgium to France, the area of La Rochelle has been declared a reception zone and Simenon, with his good connections in the area, has been appointed commissioner for Belgian refugees. Simenon later said he was responsible for 300,000 refugees over a five-month period. The biographer Patrick Marnham assumed that there would be 55,000 refugees in two months. In any case, Simenon stood up for his compatriots with commitment and organizational talent. Even after the armistice of June 22, 1940, he was responsible for the return of the refugee trains to Belgium; now he had to work together with the German occupying forces. He finally resigned on August 12th. Simenon later processed the fate of the refugees in two novels: Les Clan des Ostendais and Le Train ( filmed in 1973 ). Then he finished his work on the subject of war.

The occupation of France also had little impact on Simenon's life. Initially, as a foreigner, he had to report to the local police station on a weekly basis, but was later waived. After the house in Nieul was confiscated by German troops, the family moved three times during the war, but always stayed near La Rochelle: From 1940 the Simenons briefly lived in a farmhouse near Vouvant , then a wing of the Château de Terre -New in Fontenay-le-Comte ; in July 1942 they moved to the village of Saint-Mesmin . Everywhere, rural life enabled them to be largely self-sufficient. In the fall of 1940, Simenon was more affected than the crew by the misdiagnosis of a doctor who, after a routine X-ray, stated that his heart was "dilated and worn out", that he had only two years to live, and only if he was on alcohol, having sex , give up eating habits and physical labor. It was not until 1944 that a Parisian specialist gave the all-clear, and for the first few months after the diagnosis Simenon lived in fear of death. In December 1940 he began his autobiography Je me souviens , by means of which he wanted to record his life for his son Marc, written “by a father condemned to death”. At the suggestion of André Gide , with whom he corresponded lively at the time, he later reworked the autobiography in first-person form with changed names into the development novel Pedigree .

In June 1941, Simenon put his autobiography aside and returned to his usual work. He wrote 22 novels and 21 short stories during the war years. Production fell compared to the pre-war years, but Gallimard was able to fall back on supplies, Simenon remained present as an author, and his income was high. He also returned to his most popular creation: after a few stories published in magazines, the first new Maigret novels appeared in 1942 after an eight-year break. Stanley G. Eskin suspected the reasons for the reactivation of the retired commissioner on the one hand in the secure source of income in uncertain times, on the other hand in the recovery from the "romans durs", whose writing process was much more stressful and psychologically stressful for Simenon. He saw "Maigret as exercise, as pleasure, as relaxation".

During the war, Simenon was also present on the screen like no other French-speaking writer. Nine of his novels were made into films, five by Continental Films, founded by Joseph Goebbels and under German control . This produced a film with anti-Semitic tendencies from Simenon's innocuous original Les inconnus dans la maison . Simenon was attacked for his collaboration with Continental after the liberation of France as well as for his jury work at the Prix de la Nouvelle France , which was supposed to replace the Prix Goncourt in 1941 . When members of the Forces françaises de l'intérieur were looking for him in July 1944 , Simenon panicked, left the house and hid for several days. On January 30, 1945, he was placed under house arrest on suspicion of collaboration . The accusation could be refuted, but Simenon did not regain his freedom until May. At that point he had decided to leave France as soon as possible. He switched from Gallimard to the newly founded and more commercially oriented Presses de la Cité , which seriously damaged his literary reputation in France. In August 1945 Simenon left the European continent with a stopover in London and the destination overseas.

America

On October 5, 1945, Simenon and Tigy reached New York . Simenon, in an open mood for new impressions, immediately felt at home in the new world. He enjoyed the American way of life , democracy and the ubiquitous individualism. Because of his poor knowledge of English, he traveled on to Francophone Canada, where he rented two bungalows in Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson , northwest of Montreal , one to live in and the second to work. He then looked for a secretary and met Denyse Ouimet, who was to become his second wife, a month after his arrival. Simenon was immediately fascinated by the 25-year-old French- Canadian. In her for the first time sexual attraction and love met for him. He later described her as the most complicated woman he had ever met. He also renamed her as "Denise" because he found the spelling with y too affected. Their relationship was difficult from the start, the passion turned violent on both sides, and Simenon described: "There were moments when I was unable to decide whether I loved her or hated her."

His first novel, Trois chambres à Manhattan , written on the American continent, dealt with an encounter with Denise. With his second Maigret à New York , he also moved Maigret across the Atlantic. In the following years Simenon toured the continent. He traveled to Florida and Cuba , settled in Arizona in 1947 , first in Tucson , the following year in Tumacacori , and finally he moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea in California in 1949 . Tigy, who since the discovery of her husband's affair with Boule only lived as a friend and mother of their son at Simenon's side, accepted the ménage à trois with Denise. When boules came from France in 1948, it even became a ménage à quatre. It was not until Denise became pregnant that Tigy was divorced without this leading to a permanent separation. One of the clauses of the divorce treaty required Tigy to settle within six miles of Simenon's respective residence until Marc was of legal age. On September 29, 1949, his second son John was born. On June 21, 1950, Simenon divorced Tigy in Reno and married Denise the following day.

As of September, the new family lived on a farm in Lakeville , Connecticut . The next five years were among the most consistent and productive of Simenon's life. He wrote thirteen Maigrets and fourteen Non-Maigrets and enjoyed assimilation as an American "George". He also received literary honors in his adopted home. He was named President of the Mystery Writers of America in 1952 and elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters , and a trip to Europe in the same year was a triumphant homecoming. His fame, his reputation, his international sales success grew. On February 23, 1953 Marie-Georges - called Marie-Jo - was born, Simenon's only daughter, with whom he had a particularly close relationship. In an interview with the New Yorker , Simenon announced: “I'm one of the lucky ones. What can be said of the lucky ones except that they got away? ”He even considered US citizenship , but withdrew when his image of America began to cloud under the impact of the McCarthy era . In addition, Denise had increasing psychological problems, which he hoped to address by moving. In March 1955 a friend asked what Simenon thought about America. He gave answers that did not convince him himself. The following day he decided to leave.

Return to Europe

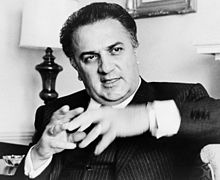

The spontaneous return to Europe took place without any concrete plans as to where Simenon wanted to spend his future. In 1955 he traveled through France with Denise, finally got stuck on the Côte d'Azur , in April in Mougins , from October in Cannes . There he became president of the jury of the Cannes International Film Festival in May 1960 . He campaigned massively for the competition winner La dolce vita by Federico Fellini , which marked the beginning of a friendship with the Italian director. Simenon's dealings with the public had changed since his return to Europe. He had reached the height of his commercial success and remained true to his scheme of alternating Maigret and Non-Maigret novels without striving for further literary developments. Despite numerous enthusiastic comments from fellow writers, the criticism in Simenon's assessment remained inconclusive. Simenon reacted with bitterness and contempt for the literary world. In 1964, he simply called the Nobel Prize Committee, which had not followed his self-confident prophecy and instead awarded it to André Gide in 1947, “those idiots who have still not given me their prize”.

Eventually Simenon settled in Switzerland, where he would spend the rest of his life. In July 1957 he moved into Echandens Castle near Lausanne . In May 1959, Simenon's third son Pierre was born, but the common child could not cover up the estrangement of the spouses. Both drank, there was mutual aggression and violence, in particular Simenon's earlier passion turned into the opposite. Denise later wrote: "He hated me as possessively as he loved me." The situation became so stressful for her that in June 1962 she was temporarily admitted to the Nyon psychiatric clinic , where she returned again in April 1964. Although Simenon refused to divorce until his death, Denise no longer lived by his side from then on. Simenon later published his diary entries from 1959–1961 under the title Quand j'étais vieux (When I was old) . The title already suggests his life crisis, which was determined by age, personal dissatisfaction and doubts about his own work.

Echandens Castle left Simenon in December 1963 due to the construction of the motorway from Geneva to Lausanne in the direction of Epalinges . The house there, planned by himself, was reminiscent of an American ranch in style and dimensions . The 22 spacious rooms were intended for children and grandchildren, but Simenon soon felt uncomfortable and lonely in the big house. After he had released Boule in November 1964 into the service of his son Marc, who in the meantime had children of his own, Teresa Sburelin remained the last woman at Simenon's side. The young Venetian had been hired as a housemaid in November 1961, soon became his lover and took care of him in old age. From 1964 to 1972 Simenon wrote 13 Maigrets and 14 Non-Maigrets in Epalinges. His last novel was Maigret et Monsieur Charles . In the summer of 1972 he planned a demanding novel under the title Oscar or Victor , which would contain his entire life experience. After a long period of preparation, he began implementing it on September 18, but the usual writing process did not materialize. Two days later, he decided to give up writing and put “sans profession” on his passport. In his memoirs Simenon wrote: "I no longer needed to put myself in the shoes of everyone I met [...] I cheered, I was finally free."

In the same year Simenon left his house in Epalinges and put it up for sale. He moved into an apartment in Lausanne, and in February 1974 he moved one last time to a small house within sight, from whose garden a large cedar loomed, allegedly the oldest tree in Lausanne. After Simenon had given up writing, he found a more convenient form of expression: the dictaphone . Between February 1973 and October 1979 he dictated a total of 21 autobiographical volumes, the so-called Dictées . However, its publication did not arouse great interest among readers and critics. In contrast, Simenon made headlines again in January 1977 with an interview. In a conversation with Fellini, he claimed to have slept with 10,000 women in his life, including 8,000 prostitutes. The biographer Fenton Bresler extensively investigated the credibility of the number. Denise said her husband was exaggerating, that together they worked out a number of 1200. However, Simenon later confirmed the number several times and explained that he wanted to recognize women through sexuality, to learn the truth about their being.

The last book Simenon published in 1981 was a fictional letter to his daughter Marie-Jo entitled Mémoires intimes , to which he attached the notes she left behind. Marie-Jo, who had had a particularly close relationship with her father from childhood - Stanley G. Eskin spoke of an electra complex - and had suffered from psychological problems since her youth, shot herself on May 20, 1978 in Paris. Her suicide was a heavy blow to the father, and the Mémoires intimes became Simenon's justification, in which he blamed Denise for the death of his daughter and denied any responsibility. Denise, for her part, published an unfriendly disclosure report about their marriage in April 1978 under the title Un oiseau pour le chat . Marie-Jo's ashes were scattered under the cedar in the garden of Simenon's house. Here he spent the last few years at Teresa's side. In 1984 a brain tumor was removed, an operation from which he recovered well. In 1988 he suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and remained paralyzed for the last year of his life. On the night of September 3rd to 4th, 1989, Georges Simenon died in the Hotel Beau-Rivage in Lausanne. His ashes, like those of his daughter, were scattered in the garden of his house.

plant

facts and figures

According to Claude Menguy's bibliography, Georges Simenon published 193 novels (including 75 maigrets) and 167 short stories (including 28 maigrets) under his name. There are also reports , essays , 21 dictées , four other autobiographical works and letters with André Gide and Federico Fellini. Simenon worked his models into scripts and radio plays , wrote plays and a performed ballet . For a detailed listing, see the list of works by Georges Simenon .

In addition to his early journalistic reports, Simenon wrote 201 penny novels and anthologies, 22 short stories and short stories in Belgian and 147 in French publications, as well as over 1000 “contes galants” (erotic stories) under a pseudonym. Simenon used the following pseudonyms: Germain d'Antibes, Aramis, Bobette, Christian Brulls, Christian Bull's, Georges Caraman, J.-K. Charles, Jacques Dersonne, La Déshabilleuse, Jean Dorsage / Dossage, Luc Dorsan, Gemis, Georges (-) Martin (-) Georges / George-Martin-George, Gom Gut / Gom-Gut (t), Georges d'Isly, Jean , Kim, Miquette, Misti, Monsieur le Coq, Luc d'Orsan, Pan, Jean du Perry, Plick et Plock, Poum et Zette, Jean Sandor, Georges Sim, Georges Simm, Trott, G. Vialio, Gaston Vial (l) is, G. Violis.

Simenon's work has been translated into more than 60 languages. He is one of the most widely read authors of the 20th century. The total circulation is often put at 500 million, but there is no concrete evidence for this number. According to statistics from UNESCO in 1989, Simenon ranks 18th among the most translated authors in the world, and in French-language literature he ranks fourth behind Jules Verne , Charles Perrault and René Goscinny . Simenon explained the worldwide success of his works with their general comprehensibility, which was due in equal measure to the deliberately kept simple style and his closeness to the "little people".

The first German translations were published in 1934 by the Schlesische Verlagsanstalt in Berlin. At that time Simenon's first name was still Germanized as "Georg". After the Second World War, Simenon's work was published by Kiepenheuer & Witsch from 1954 and a paperback edition by Heyne Verlag . Among other things, Paul Celan was responsible for two translations, which, however, are considered unsuccessful. In the early 1970s, Federico Fellini drew the publisher Daniel Keel's attention to Simenon. Its Diogenes Verlag published a Simenon complete edition in 218 volumes from 1977, which was completed in 1994. The first new editions and revised translations followed as early as 1997. A new edition of all Maigret novels was published from 2008, and 50 selected non-Maigret novels have followed since 2010. In 2017, the German-language rights were transferred to Kampa Verlag of the former Diogenes employee Daniel Kampa.

Writing process

Simenon's writing process was described in detail by him in numerous interviews and in his autobiographical works, from the plan in the calendar to the first sketches on the now famous yellow envelopes to the final telegram to the publisher. For Simenon, a novel was always heralded by a phase of restlessness and discomfort. First, he designed the characters, whose names he borrowed from a collection of telephone books. Then the yellow envelope came into play, on which Simenon recorded the characters' data and their relationships with one another. The starting point of the action was the question: “Let this person be posited, the place where he is, where he lives, the climate in which he lives, his job, his family etc. - what can happen to him, that to him forces you to go to the end of yourself? ”For more detailed elaboration, Simenon studied encyclopedias and specialist books, in some cases he even drew the plans of the locations in order to visualize them. Only a fraction of the details worked out later flowed into the actual novel, but they formed the background on which the characters developed their own life in Simenon's imagination.

To write it down, Simenon put himself in his characters and went into a kind of trance , or, as he called it, a “state of grace” that never lasted longer than 14 days. He tried to work as quickly as possible and to intervene in the writing process as little as possible. Without the plot and the end being determined in advance, he let his characters "act and the story develop according to the logic of things". The external process, however, was precisely planned and pre-marked in the calendar: Simenon wrote a chapter every morning from half past six to nine, after which his creativity was exhausted for the day. There was no break between the days so that he wouldn't lose the thread. Initially, Simenon wrote by hand and then typed the novel, later he wrote directly on the type. After completion, three days were planned for the revision, whereby Simenon restricted that he could only correct errors and not hone the text. Since it is impossible for him to explain the origin of the story, he cannot repair it afterwards either. Nor did he accept the intervention of a publisher's editor . He said he never read his books again after they were published.

In the 1920s, Simenon reached its highest production rate with the frivolous short stories. He wrote eighty pages a day, which was about four to seven stories. He typed the texts into the final version at the speed of a typist. With higher demands on his work, productivity fell: from 80 pages of trivial literature to 40 pages of crime novels per day in two sessions, after the success of the first May Rets he reduced it to 20 pages in one session. The actual writing process was just as quick, but the more demanding materials required the leisure of a longer preparation time and a recovery phase. Later it was even the Maigret novels, during whose work Simenon recovered from the more psychologically stressful “romans durs”.

style

At Colette's advice in 1923, Simenon maintained a decidedly simple and sober style. According to his own statements, he limited the vocabulary to 2000 words. A study of the Maigret novels found a vocabulary between 895 and 2300 words, 80% of which comes from the basic vocabulary and contains less than 2% of rare words. To justify this, Simenon referred to a statistic according to which over half of the French had a vocabulary of less than 600 words. He avoided any “literary” language, all “mots d'auteur” (author's words) and developed a theory of “mots matière”, those words “that have the weight of matter, words with three dimensions like a table, a house, a glass of water". For example, Simenon never described rain as “drops of water [...] that turn into pearls or similar things. I want to avoid any semblance of literature. I have a horror of literature! In my eyes, literature with a big 'L' is nonsense! "

Simenon was particularly praised for the art of his descriptions, some of which are embedded in the plot, some of which interrupt it as inserted tableaus. According to Stanley G. Eskin, Simenon was a keen and memorable observer, which enabled him to draw dense scenes that seemingly put the reader right into the action. The atmosphere of the prose is often based on the correspondence of internal and external plot elements, the subject, the character and the surrounding scenery. The weather, which influences the mood of the people involved, is always of particular importance. Simenon also keeps an eye on everyday little things in the world of his characters: the physical condition, whether as a result of a cold or new shoes, always takes precedence over the actual event. In dramatic and tragic moments, Simenon consciously sets the description of the everyday against any rising pathos . Raymond Mortimer dubbed Simenon in this regard as a "poet of the ordinary". Josef Quack spoke of a “genius of realistic visualization”.

On the other hand, the unfinished quality of Simenon's novels, which grew out of the hasty production process, was criticized. Eskin described the novels as "an extraordinary series of first drafts" that were never revised. Weaknesses can be found in the structural structure, which often does not follow a tension curve. The beginnings and ends of the novel are not always successful, the plot gets lost in dead ends or breaks off abruptly at the end. A change in the narrative perspective is sometimes used as an effective effect, but sometimes a suddenly appearing authorial narrator only serves to cover up weaknesses in the plot or narrative. On irony Simenon declined largely, and in cases where it is felt subliminally, it remains poorly designed. Because of his rejection of editing, his novels have elementary grammatical errors and recurring stylistic quirks, such as the frequent ellipses and rhetorical questions . Seldom used stylistic devices such as comparisons and metaphors show a tendency towards stereotypes and clichés .

Maigret

The novels about Maigret , Commissioner of the Criminal Police on the Quai des Orfèvres in Paris , mostly follow a fixed structure in their structure: The beginning shows Maigret in the routine of his everyday life, a life without major events. The investigation begins with the crime. The focus is less on external action - the routine work is mostly entrusted to Maigret's assistant - than on Maigret's inner process, which tries to understand what is happening. The conclusion is a final interrogation of the commissioner, which is more like a monologue of Maigret. Here, not only is the actual crime cleared up, but part of the perpetrator's previous life is rolled out. In the end there is not always an arrest, sometimes Maigret leaves the perpetrator to his fate. Typical of the Maigret novels is the transition from the initially criminological puzzle to the psychological level of exploring the motif. According to Stanley G. Eskin, this breaks with the rules of the game of the classic crime novel and disappoints some readers.

Compared to the classic detective novel, which, according to Ulrich Schulz-Buschhaus, consists of a mixture of mystery , action and analysis , Simenon has almost completely eliminated the first two elements in his Maigret novels in favor of psychological analysis. There is no longer any mystery surrounding crime, it arises from everyday life and has become everyday occurrence itself. The focus is not on the search for the perpetrator, but on understanding the act. Just as Maigret is not an eccentric detective, but a petty bourgeois integrated into the police apparatus , the perpetrators are not demonic criminals, but ordinary citizens, whose act arises from a crisis situation. The commissar and the perpetrator both become idiosyncratic figures for the reader.

Simenon described Maigret as a “raccomodeur des destins”, a “mender of fates”. His method is characterized by humanity and compassion. In particular, he regards the “little people” as “his people”, whose interactions he is more familiar with than the upper class or the aristocracy. Maigret's ethics obey the maxim “do not judge”, so he denies any moral judgment and distrusts the institutions of justice. In contrast to these, it is not primarily about facts, but about understanding a deeper human truth. Many studies emphasize the similarity of Maigret's research method with that of a writer, especially with that of his creator Simenon: like him, Maigret lives from the ability to empathize with a situation. Like this, it depends on being inspired by key stimuli in order to recognize and understand connections. Bertolt Brecht criticized Maigret's more intuitive than rational approach : "the causal nexus is hidden, nothing but fate is rolling, the detective suspects instead of thinking". Closing a case rarely turns into a triumph for Maigret. Rather, he reacts with dejection to the renewed evidence of human fallibility. Madame Maigret, the prototype of an old-fashioned and unemancipated housewife, whose role is mostly limited to keeping the food warm for her husband, becomes the dormant pole for the inspector. Simenon described her as his ideal concept of a wife.

Non-Maigret

The focus of the “romans durs”, the non-Maigret novels, is always a single figure. Simenon explained to André Gide: "I am not able to form more than one figure at a time". The protagonist is almost always male. According to Fenton Bresler, Simenon created only a few outstanding female figures in his work, such as Marguerite in Le Chat . With a few exceptions such as Aunt Jeanne , Betty and La Vieille , Lucille Becker sees the female characters only as a catalyst for the fate of the male protagonists. According to André Gide, Simenon preferred weak characters who let themselves drift, and Gide tried for a long time to develop strong protagonists. Stanley G. Eskin described the prototype of Simenon's hero as “raté”, a “failed existence”, from the unhappy in marriage, family or work suppressed “little man” with a longing for escape to the clochard . Nicole Geeraert called the characters neurotics , "who are ill-suited to the craft of being human".

In many cases, Simenon's protagonists feel a deficiency that they can compensate for a long time in their lives, until a certain event throws them off track. After they have abandoned their usual behavior, the traditional rules lose their validity. The characters break the law with a feeling of superiority or fateful impotence. The crisis ends either in the hero's downfall or in his inner damage and subsequent resignation. The structure of the “Non-Maigrets” remains largely stuck to the scheme of the Maigret crime novels: the main character is a mixture of perpetrator and victim, instead of the crime it is sometimes just a misfortune that triggers the crisis, instead of being interrogated a confession the act. However, the figure of Maigret, the "mender of fates" is missing. This is how the novels often end darkly. Without the balancing commissioner, the failed protagonists are ultimately left to fend for themselves and their existential fear. While the social conditions of the time, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s, found only limited entry into the novels, Simenon was often inspired by the dark side of his own biography, by the family circumstances of the Simenons and Brülls, his turbulent youth, the frequent motive of slipping into crime to the unhappy second marriage. The scenes also follow Simenon's frequent changes of location, albeit with a delay: "I cannot write about the place where I currently live."

Simenon summarized his work as a search for the "l'homme nu" - the "naked person" understood as "the person who is common to all of us, only with his basic and primal instincts". Simenon's characters are, without realizing it, predetermined in their existence by instincts and drives . According to Nicole Geeraert, Simenon draws a deterministic and pessimistic view of man. For Hanjo Kesting , the plot “almost always has a fatalistic trait, an element of inescapability and fate.” In his first Maigret novel Pietr-le-Letton , Simenon developed the “theory of the tear”, of the “moment in which behind the human appears to the player ”. It is this existential leap that Simenon works out in the life stories of his characters. It often leads to the “acte gratuit”, an act without a motive. For the literary critic Robert Kanters, "Balzac was the writer with whom man develops, with Simenon he breaks."

Literary role models and position in crime literature

Simenon was shaped early on by Russian literature , which, according to his own statements, was formative in particular for his “romans durs”. With Gogol , for example, his relationship to the “little people” connected him: “In my life I haven't looked for the heroes with big gestures, with big tragedies, but I took on the little people, gave them a heroic dimension without theirs insignificant identity and their little life. ” Chekhov influenced him with the importance of the social milieu . As with Chekhov, his characters do not know each other, but are on the lookout: "The author does not try to explain them, but lets their complexity affect us." From Dostoyevsky he adopted a changed concept of guilt: "Guilt is no longer a simple, clear offense, as it is in the criminal code, but becomes a personal conflict for each individual. "

On the other hand, classic crime fiction had hardly any influence on Simenon's work. He was not very interested in other crime writers and read only a few crime novels. Julian Symons assessed: "The Maigret novels stand on their own in the field of crime fiction, yes they have little relation to the other works of the genre." The French detective novel was previously in the tradition of adventure novels and fantastic literature . It was only through Simenon that the level of realism found its way into French-language crime literature. Pierre Assouline saw Simenon as the starting point for a new French crime novel independent of American tradition. Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac went even further , according to which Simenon did not write any detective novels. Although he uses the technology of the genre, but with his focus on the background of human behavior, “one cannot count him among the detective novelists. Thanks to a misunderstanding, Maigret is considered one of the greatest detectives. "

Nevertheless, Simenon became groundbreaking for a new, psychologically shaped type of crime fiction which Boileau and Narcejac or Patricia Highsmith represented after him . The first German-language crime writer of importance, Friedrich Glauser , also followed his example: “In one author I found everything that I missed in all of the crime literature. The author's name is Simenon [...] I learned what I can do from him. ”For Thomas Wörtche , Simenon remained“ [a] on the European mainland a solitaire, but immensely momentous. ”He most consistently crossed the line between crime fiction and literature and thus anticipated the problems of later crime literature, which cannot be classified into the current crime fiction scheme.

reception

Contemporary recording

The Maigret novels became an instant hit in 1931. In autumn, the publisher named Hachette Simenon as bestseller of the year. The press showed interest from the start and judged largely with great approval. Positive reviews praised the style and quality of the descriptions and came to the conclusion that Simenon was raising the detective novel to a more serious and literarily higher quality level. Mixed reviews often insisted on the inferiority of the genre, in which Simenon showed technical skills, the rare bad reviews simply felt bored by the author. Simenon was compared to other prolific writers like Edgar Wallace , Maigret was already placed on a par with Sherlock Holmes . The writer and journalist Roger DEVIGNE took La guinguette à deux sous in a selection of the ten greatest masterpieces by 1918, the writer and critic Jean Cassou discovered in Simenon's novels more poetry than in most poetic works. Stanley G. Eskin summarized: Simenon had become “in” in 1931.

Within a few months, the Maigret novels were translated into eight languages. In England and the USA the reviews were mixed. The Times Literary Supplement wrote of "well-told and skilfully constructed stories" which Saturday Review criticized: "The story is better than the detective". One exception was Janet Flanner , who in a euphoric meeting at the New York Simenon said she was “in a class of her own”. It took Simenon a long time to establish itself in the German-speaking market. After a few issues before and after the war, it was not until 1954 that the Maigret series by Kiepenheuer & Witsch became a great success.

Simenon's first non-Maigret novels were also largely received positively by critics in the 1930s. There were two basic lines of reviews: some saw Simenon as a crime writer who tried his skills on higher literature, others as a writer who had always stood out above the genre of the crime novel. In many cases, individual novels were singled out that, from the point of view of the critic, marked the breakthrough in Simenon's work towards upscale literature. Stanley G. Eskin called this a game that was to be found again and again in Simenon's reception for the next ten to twenty years. The literary critic Robert Kemp called Simenon's works "half popular novel, half detective novel" to add, "they seem to me to be of great value". His colleague André Thérive judged Les Pitard to be “a masterpiece in its purest form, in an unadulterated condition”. Paul Nizan , however, contradicted: "It suddenly becomes clear that he was a decent writer of detective literature, but that he is an extremely mediocre writer of completely normal literature."

During the eight years in which Simenon had turned away from Maigret and only published "romans durs", his sales figures were declining. It is true that his reputation as a serious writer was consolidated. But he was still mainly perceived in public as the creator of Maigret, even as the one who had stopped writing Maigret novels. During his years in America, the "Simenon case" continued to be discussed in the French press, but no longer with the same attention that had prevailed before the Second World War. Eskin described an uncertainty in the ratings as to how Simenon should be classified, he didn't fit into any drawer. In the US, on the other hand, interest increased and his novels became bestsellers. The first books on Simenon appeared in the 1950s, starting with Thomas Narcejac's Le Cas Simenon , in which Simenon is placed above Camus , to a Soviet monograph. In addition to receiving American honors from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Mystery Writers of America , Simenon was accepted into the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Belgium in 1952 . In 1966 he received the Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America, and in 1974 the Swedish Crime Academy named him a Grand Master .

From the mid-1950s until the end of his writing career, Simenon's reputation remained at a high level. Individual admirers fought against the widespread Maigret image and propagated him as a serious writer, but in general Simenon's reception remained ambiguous. According to Patrick Marnham, the change of publishing house from the renowned Editions Gallimard to the commercially oriented Presses de la Cité also damaged Simenon's literary reputation in France and stood in the way of higher literary awards. The later autobiographical works could no longer improve Simenon's reputation. Quand j'etais vieux received mixed reviews. The Guardian, for example, spoke of a “male menopause,” and The Sunday Telegraph simply commented: “Hmm!” The Dictées did not reach a large readership, unlike the Mémoires intimes , which received great interest but poor reviews because of their revelations.

The "Simenon Case"

For the analysis of Simenon's work, a motto was established early on: "le cas Simenon - the Simenon case". The term goes back to Robert Brasillach , who had already worked out two opposing characteristics of Simenon in 1932: his talent, the ability to observe and his feeling for atmosphere on the one hand, the negligence in implementation, superficial constructions and a lack of literary education on the other. The term drew itself through numerous reviews for the next fifteen years and eventually became the title of the first treatise in book form on Simenon by Thomas Narcejac. In 1939, the “Simenon case” had become a “Simenon adventure” for Brasillach, and he wished Simenon would look for other literary shores: “If someone should one day be able to write the great novel of our time, then [ …] The greatest prospect that it is this young man ”.

François Bondy used the term “The Miracle of Simenon” in 1957, not to describe Simenon's maturation “from mediocre colportage to genuinely literary works”, but for the “fact that both his work and its evaluation remain in the twilight despite everything. "He described a path" from the virtuosity of the all-rounder to intensive concentration and simplification. " Alfred Andersch spoke of a" riddle "Simenon, as the most famous and most widely read French writer in 1966 in the two representations of contemporary French literature by Maurice Nadeau and Bernard Pingaud was absent: “It's a riddle. It gives one the suspicion that our whole concept of literature could be wrong. ”For Jean Améry too ,“ the Simenon case was quite unique in modern literature ”, he described it as“ The Simenon phenomenon - a storyteller that is perhaps unique today, combined with a no less unprecedented working capacity ”. Simenon himself resisted the term “cas Simenon”: “I am not a case, I would be horrified to be a 'case'. I'm just a novelist, that's all ”. He referred to role models such as Lope de Vega , Dickens , Balzac, Dostoevsky and Victor Hugo . In the present no one writes like them anymore, which is why he, the traditional novelist, is nowadays seen as a "case".

For the publisher Bernard de Fallois it was “Simenon's greatest merit to have revalued reading, […] to have reconciled art and the reader.” His novels are for the reader “a means of self-knowledge and almost the answer for his personal skill. ”Similarly, the literary critic Gilbert Sigaux, editor of Simenon's works, wrote that Simenon forced the reader to“ look at himself ”. He asked “not: who killed ?, but: where are we going? What is the point of our adventure? ”In this respect, all of Simenon's novels belonged to“ one and the same novel ”. Georg Hensel added: “If you want to find out in the 21st century how people lived and felt in the 20th century, you have to read Simenon. Other authors like to know more about society than he does. Nobody knows as much about the individual as he does. ”For Thomas Narcejac, Simenon ranked among the seekers with his“ refusal to portray characters, from humans to events or to intrigue ”, and belonged to the circle of existentialism . Jürg Altwegg saw it as Simenon's greatest achievement “to derive and explain his characters from their respective milieu”, and he described him as the “ Goethe of the silent majority”: “ Zola and others have already made the underprivileged the subject of their best works. But only Simenon was able to win these masses as readers. "

be right

Simenon is one of the rare cases of a popular bestselling author who was also highly valued by fellow writers. One of his first admirers in 1935 was Hermann Graf Keyserling , who called Simenon a “natural wonder” and gave him the title “Idiot Genius”, of which Simenon was very proud. An early friendship connected him with André Gide , who wrote in 1939 “that I consider Simenon a great novelist, perhaps the greatest and most genuine novelist that French literature possesses today.” In America, Henry Miller became a friend of his Judged, “He is everything a writer wanted to be, and he remains a writer. A writer outside of the norm, as everyone knows. It is really unique, not just today, but at any given era. ” Given the size of the work, his late friend Federico Fellini said:“ I could never believe that Simenon really existed. ”

Many authors of world literature were among Simenon's readers. William Faulkner confessed: “I enjoy reading Simenon's crime novels. They remind me of Čechov . " Walter Benjamin did the same:" I read every new novel by Simenon. " Ernest Hemingway praised the" wonderful books by Simenon ". Kurt Tucholsky wrote: “This man has the great and so rare gift of epic storytelling without telling anything . His stories usually have no content at all [...] And you can't put the book down - it tears you up, you want to know how it goes on, but it doesn't go on at all. […] It's completely empty, but what colors is this pot painted with! ” Thornton Wilder judged:“ Narrative talent is the rarest of all talents in the 20th century. [...] Simenon has this talent right down to his fingertips. We can all learn from him. ”From Gabriel García Márquez's point of view , he was even“ the most important writer of our century ”.

Many crime writers in particular admired Simenon. For Dashiell Hammett he was “the best crime writer of our day”, for Patricia Highsmith “the greatest narrator of our days”, for WR Burnett “not only the best crime writer, he is also one of the best writers par excellence.” Friedrich Glauser praised them Maigret series: “The novels are almost all written according to the same scheme. But they are all good. There is an atmosphere in it, a not cheap humanity, a signing of the details ”. John Banville wrote his first detective novel because he was "blown away by Simenon". Cecil Day-Lewis admitted that "with his best detective novels he is entering a dimension that his colleagues cannot reach."

The number of Simenon's admirers, in turn, attracted critics. For Julian Barnes , it was "an at times somewhat embarrassing admiration" that some great writers showed Simenon. Philippe Sollers described: "The fact that Gide - after rejecting Proust - regarded him as the greatest writer of his time is irresistible comedy." Jochen Schmidt also considered Simenon "far overrated". His reputation as a “great writer” is “one of those truisms that already have a somewhat bland aftertaste”.

Effect and aftermath

Simenon's novels have often been made into films, see the list of film adaptations of the works of Georges Simenon . By 2010, a total of 65 films and 64 international television productions were made, including series that were produced over many years. The series about Commissioner Maigret of French television with Jean Richard (88 episodes from 1967 to 1990), the subsequent film adaptations with Bruno Cremer (54 episodes from 1991 to 2005) and the BBC series with Rupert Davies (52 episodes from 1960 ) remained the most extensive until 1963).

In 1976, under the direction of the literary scholar Maurice Piron , the Center d'études Georges Simenon was founded at the University of Liège . It is dedicated to researching the life and work of Georges Simenon and has been publishing the annual Traces since 1989 . Simenon donated his manuscripts, working papers and professional memorabilia to the institution, which are kept there in the Simenon Fund . In 1989, the international association Les Amis de Georges Simenon was established in Brussels , which since then has published Cahiers Simenon and other research publications as well as previously unpublished texts annually . The German-speaking Georges Simenon Society was founded in 2003. She published three yearbooks between 2003 and 2005.

On Simenon's 100th birthday, the region around Simenon's native Liège declared 2003 Wallonie 2003, Année Simenon au Pays de Liège , Simenon year, in which various exhibitions and events related to the writer took place. In this context, the musical Simenon et Joséphine, about Simenon's relationship with Josephine Baker, premiered on September 25, 2003, and premiered at the Opéra Royal de Wallonie in Liège. In the following year a statue of Simenon was erected on the new Place du Commissaire Maigret . The Résidence Georges Simenon in Liège , built in 1963, had already been named after him. He is also remembered regularly in Simenon's adopted home on the French Atlantic coast: In the area around Les Sables-d'Olonne , a Simenon festival has been held every year since 1999 in honor of the writer . The difference in popularity in Belgium on both sides of the language border was demonstrated by an audience vote on Belgian television in 2005, in which the “greatest Belgian” was voted on. While Simenon was ranked 10th in the Walloon edition Le plus grand Belge , he landed in 77th place in the Flemish counterpart De Grootste Belg .

Works and film adaptations

literature

Biographies

- Pierre Assouline : Simenon. A biography . Chatto & Windus, London 1997, ISBN 0-7011-3727-4 (English).

- Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. In search of the "naked" person . Ernst Kabel, Hamburg 1985, ISBN 3-921909-93-7 .

- Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. A biography . Diogenes, Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-257-01830-4 .

- Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1991, ISBN 3-499-50471-5 .

- Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures . Diogenes, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-257-06711-8 .

- Patrick Marnham: The man who wasn't Maigret. The life of Georges Simenon . Knaus, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-8135-2208-3 .

To the work

- Hans Altenhein: Maigret in German. The story of a relationship . In: From the Antiquariat 2, NF18, Frankfurt 2020, ISSN 0343-186X. A history of Simenon translations into German.

- Arnold Arens: The Simenon Phenomenon . Steiner, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-515-05243-7 .

- Lucille F. Becker: Georges Simenon . House, London 2006, ISBN 1-904950-34-5 (English).

- Hanjo Kesting : Simenon. Essay . Wehrhahn, Laatzen 2003, ISBN 3-932324-83-8 .

- Claude Menguy: De Georges Sim à Simenon. Bibliography . Omnibus, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-258-06426-0 (French).

- Josef Quack: The limits of the human. About Georges Simenon, Rex Stout, Friedrich Glauser, Graham Greene . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2000, ISBN 3-8260-2014-6 .

- Claudia Schmölders , Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon . Diogenes, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-257-20499-X .

documentary

- The century of Georges Simenon. Documentary, France, 2013, 52 Min, written and directed by. Pierre Assouline , production: Cinétévé, Les Films du Carré, RTBF Secteur Document Aires, INA , arte France, Simenon.tv, first broadcast: February 23, 2014. arte, Summary of arte.

Web links

- Literature by and about Georges Simenon in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Georges Simenon in the German Digital Library

- maigret.de - Information on life, work and films

- Le Center d'études Georges Simenon et le Fonds Simenon of the University of Liège (French)

- Georges Simenon. 100th birthday in 2003 . 20-page booklet by Diogenes Verlag (PDF)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The official birth certificate is dated February 12, 1903, 11:30 p.m. According to Simenon's statement, he was actually born on February 13 at 12:10 a.m. and the date was later backdated. Compare Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 30.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 30.

- ↑ See section: Patrick Marnham: The man who was not Maigret. Pp. 34-52, citation p. 52.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 50-58, quoted on p. 50.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 295-296.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 41–42, quotation p. 42.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. S. 11. Other sources give 1909 as the year of school entry.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 56-57.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 63, 66.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 70.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 73-74.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 74-82.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 83.

- ↑ Quoted from: Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 27.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. Pp. 54-55.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 88-91. Quote p. 90.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 88-92.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 105-106.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 80.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 12, 107-108.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 81-83.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 12, 123-125.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 131-134, 146, citation p. 132.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 152-156.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 102-107, citation p. 105.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 112-116, citation p. 116.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 120-126.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 163, 168-169.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 109.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 282.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 164-165.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 170-172, citation p. 171.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 174-176.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 176-180, 202, citations p. 202.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 180-185.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 165-174.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 177, 181, 188.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 216-218.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 10.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Quoted from: Patrick Marnham: The man who was not Maigret. P. 204.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 249-254.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 75.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 254-255.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 259-264, citation p. 264.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 260, 268, 272.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 244-245, quoted p. 245.

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Was Not Maigret. Pp. 278-302.

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Was Not Maigret. P. 305.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 275-276.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 306-314, citation p. 313.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 16, 310, 312.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 327-329, 332-33.

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Was Not Maigret. Pp. 334-358, citation p. 355.

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Was Not Maigret. Pp. 359-361, 366, 368-369, citation p. 361.

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Was Not Maigret. Pp. 370, 373, 381-387.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 340.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 372, 384, 392-393, 397.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 362, 372-373.

- ↑ Quotation from: Patrick Marnham: The man who was not Maigret. P. 401.

- ↑ Quotation from: Patrick Marnham: The man who was not Maigret. P. 408.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 378-381.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. Pp. 20-21, 358-367.

- ↑ Cf. Felix Philipp Ingold: When the daughter with the father. In: full text. Retrieved August 18, 2020 .

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 368.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 404-408, 412-414.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 105.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. P. 207.

- ^ Camille Schlosser: Georges Simenon. Life, novels, stories, films, theater. In: du 734, March 2003, p. 81.

- ↑ Claude Menguy: De Georges Sim à Simenon. Pp. 15-16. Menguy counts 1225 titles of the "contes galants", but points out that some stories have appeared under several titles and considers "a good thousand" to be a cautious estimate.

- ↑ Cf. Claude Menguy: De Georges Sim à Simenon. Pp. 257-258.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. P. 310.

- ^ A b Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 433.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. P. 313.

- ↑ Stefan Zweifel : This time murdered: The text. How Celan failed as a Simenon translator. In: du 734, March 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. P. 311.

- ↑ Philipp Haibach: Inspector Maigret is getting a divorce . At: welt.de , August 16, 2017; Retrieved on August 17, 2017. See also in: Die Welt from August 17, 2017, p. 21.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. Pp. 262-263, citation p. 263.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 34.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. Pp. 263-279, citations pp. 265, 269.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 160.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 33.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 201-202.

- ↑ See Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 245.

- ^ Hans-Ludwig Krechel: Structures of the vocabulary in the Maigret novels of Georges Simenons . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-8204-5913-8 , pp. 220, 227. Cf. Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 53.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. P. 16.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 299, 433.

- ^ Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 36, quotation p. 36.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. P. 17.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 435.

- ↑ Josef Quack: The limits of the human. Pp. 14-15.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. P. 257.

- ↑ Josef Quack: The limits of the human. P. 13.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 425-426, quoted p. 425.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 427-433, quoted p. 431.

- ^ Hans-Ludwig Krechel: Structures of the vocabulary in the Maigret novels of Georges Simenons. P. 227. See Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. Pp. 53-54.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. Pp. 49-52.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 411.

- ^ Ulrich Schulz-Buschhaus : Forms and ideologies of the crime novel. An essay on the history of the genre. Athenaion, Frankfurt am Main 1975, ISBN 3-7997-0603-8 , pp. 1-5.

- ^ Arnold Arens: The Simenon Phenomenon. Pp. 32-33.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 392-407.

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht : Journals 2 . Volume 27 of the works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt edition . Structure, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-351-02051-1 , p. 84.

- ↑ a b Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 41.

- ↑ Lucille F. Becker: Georges Simenon revisited . Twayne, New York 1999, ISBN 0-8057-4557-2 , p. 58.

- ^ Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 50, quotation p. 55.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. P. 362.

- ↑ Lucille F. Becker: Georges Simenon. P. 121.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 290.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 440-441.

- ^ A b c Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 66.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. Pp. 60-66.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 188.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 182.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 299.

- ^ Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 28.

- ^ Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 40.

- ^ Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 30.

- ↑ Robert Kanters: Simenon - the anti-Balzac. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 92-99, quoted on p. 96.

- ↑ Francis Lacassin : "So you're the novelist of the unconscious?" . Interview with Georges Simenon. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. P. 209.

- ↑ Quoted from: Eléonore Schraiber: Georges Simenon and the Russian literature. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. P. 144.

- ↑ Eléonore Schraiber: Georges Simenon and the Russian literature. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 145-146, citation p. 146.

- ↑ Eléonore Schraiber: Georges Simenon and the Russian literature. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 147-148, citation p. 148.

- ↑ Julian Symons : Simenon and his Maigret In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Hrsg.): About Simenon. Pp. 123-129, quoted p. 129.

- ^ Karlheinrich Biermann, Brigitta Coenen-Mennemeier: After the Second World War. In: Jürgen Grimm (Ed.): French literary history . Metzler, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-476-00766-9 , p. 364.

- ^ Pierre Assouline : Simenon. Biography . Julliard, Paris 1992, ISBN 2-260-00994-8 , p. 141.

- ↑ Pierre Boileau , Thomas Narcejac : The detective novel . Luchterhand, Neuwied 1967, p. 126.

- ^ Arnold Arens: The Simenon Phenomenon. P. 33.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser in the Lexicon of German Crime Authors.

- ↑ Thomas Wörtche: The failure of the categories . Lecture on the page kaliber.38 .

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 149, 167-170.

- ^ Fenton Bresler: Georges Simenon. P. 123.

- ↑ Quotes from: Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 168-171.

- ^ Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 55.

- ↑ Quotes from: Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 190-193.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 267.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 235, 244.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 297-299.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 314, 316, 325.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 349-351.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 299.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 371-372.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 380-381.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. Pp. 170, 297, 314.

- ^ Stanley G. Eskin: Simenon. P. 236.

- ^ François Bondy : The Miracle Simenon. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 71–79, citations pp. 71, 73.

- ^ Alfred Andersch : Simenon and the class goal. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 111-114, citation pp. 113-114.

- ↑ Jean Améry : The hardworking life of Georges Simenon. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 102-110, citations pp. 102, 110.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. Pp. 398-399, citation p. 399.

- ↑ Bernard de Fallois: Simenon - this unpunished vice. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 86-91, citations pp. 88, 91.

- ↑ Gilbert Sigaux: Read Simenon. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 139-143, citations pp. 139, 143.

- ↑ Georg Hensel : Simenon and his commissioner Maigret. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 151-165, citation pp. 156-157.

- ↑ Thomas Narcejac : The Omega Point In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 134-138, citation p. 137.

- ↑ Jürg Altwegg : The Goethe of the silent majority. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. Pp. 173-178, citations pp. 173, 176, 178.

- ↑ Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. P. 300.

- ↑ Patrick Marnham: The Man Who Wasn't Maigret. P. 246.

- ↑ Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. P. 43.

- ↑ Quoted from: Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. P. 122.

- ↑ Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. P. 65.

- ↑ a b Quotations from: Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. P. 301.

- ↑ Quoted from: Alfred Andersch: Simenon and the class goal. In: Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. P. 114.

- ↑ Quoted from: Hanjo Kesting: Simenon. P. 53.

- ↑ Quotations from: Daniel Kampa et al. (Ed.): Georges Simenon. His life in pictures. Pp. 300-301.

- ↑ Claudia Schmölders, Christian Strich (Ed.): About Simenon. P. 64.

- ↑ Julian Barnes : The goat. In: du 734, March 2003, p. 23.

- ↑ Quoted from: Nicole Geeraert: Georges Simenon. Pp. 123-124.