Friedrich Glauser

"Even when I felt really bad, I always felt as if I had something to say, something that nobody but me would be able to say in this way."

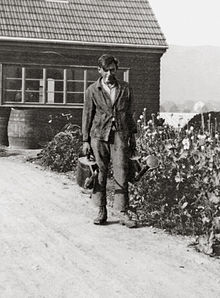

Friedrich Charles Glauser (born February 4, 1896 in Vienna , Austria-Hungary ; † December 8, 1938 in Nervi near Genoa ) was a Swiss writer whose life was marked by incapacitation , drug addiction and internment in psychiatric institutions. Nevertheless, he achieved literary fame with his stories and feature pages , but above all with his five Wachtmeister Studer novels. Glauser is considered to be one of the first and at the same time most important German-language crime writers .

Glauser about Glauser

On June 15, 1937, Glauser wrote in a letter to the journalist and friend Josef Halperin in connection with the publication of the Foreign Legion novel Gourrama :

«Do you want data? So, born in 1896 in Vienna by Austrian mother and Swiss father. Paternal grandfather gold digger in California (sans blague), maternal councilor (nice mix, eh ?). Elementary school , three classes high school in Vienna. Then 3 years in the Glarisegg State Education Center . Then 3 years at the Collège de Genève . Thrown out shortly before graduation because I wrote a literary article about a book of poetry by a teacher at the local college. Cantonal Matura in Zurich . 1 semester of chemistry . Then dadaism . Father wanted to have me interned and put under guardianship. Escape to Geneva. [...] Interned in Münsingen for one year (1919) . Escape from there. 1 year Ascona . Arrested because of Mo. ['Mo.' stands for the drug morphine , on which Glauser was heavily dependent during long phases of his life]. Return transport. 3 months Burghölzli (counter-expertise, because Geneva had declared me schizophrenic). 1921–23 Foreign Legion. Then Paris Plongeur [dishwasher]. Belgium coal mines. Later a nurse in Charleroi . Interned in Belgium again on Monday. Transport back to Switzerland. 1 year administrative Witzwil . Afterwards 1 year handyman in a nursery . Analysis (1 year) while I continued to work as a handyman in a tree nursery in Münsingen. As a gardener to Basel , then to Winterthur . During this time he wrote the legionary novel (1928/1929), 30/31 year course in Oeschberg horticultural school . July 31 follow-up analysis. January 32 to July 32 Paris as a 'freelance writer' (as the saying goes). To visit my father in Mannheim . Stuck there for wrong prescriptions. Transport back to Switzerland. Interned from May 32 to May 36. Et puis voilà. Ce n'est pas très beau, mais on fait ce qu'on peut. "

Life

Friedrich Glauser's life was a vicious circle of addiction to morphine , lack of money, and crime against acquisitions and ended up in hospitals again and again; until the next discharge, until the next suicide attempt, until the next attempt to escape. In total he spent eight years of his life in clinics; In 1932 he mentions morphine in his autobiographical story : "I was never really satisfied until I was in prison or in an asylum." In addition to his literary work, Glauser worked as a servant, milk delivery worker, worker in an ammunition factory, bookseller, private teacher, stoker, translator, businessman, journalist, foreign legionnaire, dishwasher, mine worker, nurse, librarian, bookbinder, cleaner, organist, gardener and as a self-nourisher a farm. He found his final resting place in the Manegg cemetery in Zurich .

"An uncomfortable son": childhood and adolescence (1896–1916)

Friedrich Charles Glauser was born on February 4, 1896 in Vienna as the son of the Swiss teacher Charles Pierre Glauser and his wife Theresia, née Scubitz, from Graz. In 1900 she died of appendicitis ; the father seemed overwhelmed by giving his son the lack of maternal security and instead demanded performance, to which the boy reacted with increasing rebellion. In 1902 Charles Pierre Glauser married Klara Apizsch. In the same year Friedrich Glauser entered the Protestant elementary school on Karlsplatz and four years later the Elisabeth Gymnasium, where he had to repeat the third grade. In 1909, father and stepmother separated, and Glauser's grandmother took over the role of educator, since the father was appointed to the commercial college in Mannheim . In the summer of this year, the 13-year-old escaped alone across the Slovak border to Pressburg , where he was picked up by the police and taken back to Vienna. The relationship between Glauser and his father became increasingly difficult and remained a central and at the same time conflict-laden topic. After this escape from the parental home, the father took the boy out of school and at the beginning of the school year 1910 sent him to the Glarisegg rural education center in Steckborn, Switzerland . In 1911 Charles Pierre Glauser married a third time, this time Louise Golaz from Geneva , who lived as governess in the Glauser house, and moved permanently to Mannheim, where he was henceforth rector of the commercial college.

As a result, new problems arose in the Glarisegg Rural Education Center: Glauser ran into debts in the surrounding villages and dealt a blow to the Latin teacher Charly Clerc because he had put him in front of the door. When he attempted suicide using chloroform in 1913 , he was forced to drop out of school. He then completed six months of land service with a farmer near Geneva and then entered the Collège Calvin (until 1969 "Collège de Genève") in September . In the first year he lived with his (step) aunt Amélie (the sister of father Glauser's third wife); Glauser's drug addiction also began in the diplomatic capital: “The pharmacist from whom I got ether, a little hunchbacked man, gave me morphine at my request, without a prescription. […] And so the accident began. [...] Food was secondary, what I earned, the pharmacist got. " In 1915 Glauser graduated from the Swiss Army recruit school as a mountain artilleryman in Thun and Interlaken . He was proposed as a non-commissioned officer , but during his training he turned out to be “limp, lackluster, absolutely unable to hold his degree”. He was then dismissed from the army as unfit for service. Again in Geneva on "Collège" he discovered his literary talent and published as a young high school student by the name of Frédéric Glosère or the pseudonym "Pointe-Sèche" (German: Radiernadel ) his first texts in French in L'Independence HELVETIQUE ; by 1916 Glauser wrote nine reviews and essays in a predominantly provocative style. For this reason, there was a scandal in 1916, as a result of which Glauser threatened to be expelled from school. The reason for this was his devastating criticism of Un poète philosophe - M. Frank Grandjean (1916) on the collection of poems by the college teacher Frank Grandjean. Because of the possible exclusion from school, Glauser left the “Collège” after he reached the age of majority, broke off his relationship with his parents and moved to Zurich to take his Matura.

→ Detailed chapters :

→ Autobiographical texts from this period of life:

- Morphine. (1932)

- In the rural education home. (1933)

- Writing ... (1937)

- Cracked glass. (1937/38)

- Back then in Vienna. (1938)

- The small. (1938)

“Escape from Time”: Dadaism, Ticino and Baden (1916–1921)

After Glauser had left the Collège in Geneva because of the possible exclusion from school, he passed the Matura at the Minerva Institute in Zurich in April 1916 and enrolled as a chemistry student at the university . At the same time he founded the literary magazine Le Gong - Revue d'art mensuelle with Georges Haldenwang , which only appeared three times. In autumn Glauser broke off his chemistry studies, came into contact with the Dada movement and from then on led an artist's life. He got to know various personalities such as Max Oppenheimer , Tristan Tzara , Hans Arp , Hugo Ball from Cabaret Voltaire , the birthplace of Dadaism, and his later wife Emmy Hennings . On March 29 and April 14, 1917, Glauser took an active part in Dada soirees, but ultimately stayed away from the art movement. Driven by his addiction to morphine, Glauser repeatedly committed criminal offenses, betrayed friends and acquaintances, committed theft and falsified recipes. For the first time, Glauser's father refused to continue paying his son's debt. He applied for a psychiatric examination and turned on the Zurich custodianship, whereupon Glauser left for southern Switzerland. There he spent from June to mid-July with Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings in Magadino and later on Alp Brusada in the Maggia Valley (in the Valle del Salto , around 7 kilometers northeast of the village of Maggia ). In July 1917 Glauser traveled to Geneva and worked briefly as a milk carrier in a yoghurt factory and then returned to Zurich.

In January 1918 Friedrich Glauser was incapacitated. He fled again to Geneva and was arrested in June after further thefts and admitted to the Bel-Air Psychiatric Clinic for two months as a morphine addict. There he was diagnosed with " dementia praecox ". He then came to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center for the first time , where he would spend almost six years of his life. In July 1919 Glauser fled Münsingen, this time back to Ticino, and found accommodation with Robert Binswanger in Ascona . The village at Lake Maggiore below the Monte Verita at the time was a magnet for artists' colonies , bohemians , political refugees, anarchists , pacifists and followers of different alternative movements. Glauser made the acquaintance of a number of personalities such as Bruno Goetz , Mary Wigman , Amadeus Barth , Marianne von Werefkin , Alexej von Jawlensky , Paula Kupka , Werner von der Schulenburg and Johannes Nohl . He worked on several texts, but did not find the necessary calm: «A circle of friends had taken me in a way I could not have wished for more warmly. And yet it was barely two months before I longed for solitude again. " Glauser fell in love with Elisabeth von Ruckteschell, who was ten years his senior, who was also staying with Binswanger at the time, and moved with her in November 1919 to an empty mill near Ronco . The two lived there until the beginning of July 1920. Then the romance ended abruptly: Glauser became addicted to morphine again and was arrested in Bellinzona . There he tried to take his own life for the second time by trying to hang himself in a holding cell . He was then transferred to the Steigerhubel insane asylum in Bern. On July 29th, with the help of Elisabeth von Ruckteschell, he managed to escape from there by taxi.

After a stay in the “Burghölzli” psychiatric clinic , he found accommodation in Baden with the town clerk Hans Raschle and his wife “Maugg”, who wanted to give the stumbled man a new chance. Raschle tried to work for Glauser at Brown, Boveri & Cie. to arrange, which however did not materialize. Instead, he did a traineeship at the Badener Neue Freie Presse and wrote articles for the Badener Tagblatt and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung . After the relationship with Elisabeth von Ruckteschell finally broke up towards the end of the year, Glauser began an affair with Hans Raschle's wife behind the back of Hans Raschle. He also began to soak his cigarettes with opium , forged morphine recipes again, drank ether and sold Raschle's books at a bookseller. In April 1921 Glauser rushed deliriously at "Maugg", as a result of which she turned her husband's orderly pistol against the attacker. On the evening of the same day Glauser disappeared without saying goodbye and fled across the German border to his father in Mannheim . Once there, he advised his son to join the French Foreign Legion .

→ Detailed chapters :

→ Autobiographical texts from this period of life:

- A thief. (1920)

- CV Burghölzli. (1920)

- Burghölzli diary. (1920)

- Medical history, written by the patient himself. (1920)

- Dada. (1931)

- Ascona. Fair of the Spirit. (1931)

- Confession in the night. (1934)

- Ascona Roman fragment . (1937/1938)

"At a loss": Foreign Legion (1921–1923)

(the dates refer to the arrival)

When Glauser was 25 years old, he had already had a number of disasters. His biographer Gerhard Saner writes: "The father wanted to finally, finally have peace, the guarantee of the most secure safekeeping." Glauser's father saw in the French Foreign Legion an opportunity to put an end to all the problems and to give up a tiresome responsibility. Friedrich Glauser was accepted into the Foreign Legion in Strasbourg on April 29, 1921 and signed an engagement for five years. In May two corporals and an adjutant from Sidi bel Abbès picked up the freshly dressed recruits and traveled with them to Marseille . Eight days later they embarked on the steamer "Sidi Brahim" at 5:00 am for the crossing to Oran . In mid-May 1921 Glauser arrived in Algeria and traveled from Oran to the garrison town of Sidi bel Abbès. He went to the sergeant school for the machine gun department, where he was appointed corporal four months later . On June 21, Glauser joined his troops, became the captain's secretary and worked in the Fourier service. In the summer the whole battalion was moved to Sebdou, around 150 kilometers southwest of Sidi bel Abbès, and quartered there. It was bored and a wave of desertions seized parts of the troops; Glauser himself did not take part. This was followed by a punitive transfer of the battalion to Géryville (after the French colonial era El Bayadh ), a garrison in the middle of a high plateau at an altitude of 1,500 meters. The postponement lasted from December 17th to December 26th. Here too, as in Sebdou, the boredom of garrison life prevailed. Glauser reported to the troop doctor about heart problems, was transferred to the office and was often on sick leave. At the end of March 1922, twelve volunteers were wanted for Morocco . Glauser volunteered, was selected, and in May the detachment began moving to the Gourrama outpost .

The legion's outpost in southern Morocco between Bou-Denib and Midelt was next to two Berber villages and had quartered almost 300 men. The legionnaires' tasks were limited to drills , shooting exercises, marching out and, if necessary, protecting a train with food, as bands of robbers ( Jishs ) made the area unsafe. During the first medical examination, Glauser was declared unfit for marching and then came back to the administration, where he was responsible for the food and around 200 sheep and 10 cattle. However, he cheated on weights, gave unauthorized food rations and manipulated the bookkeeping with the consent of superiors. Fearing possible consequences, Glauser began to drink alcohol in excess. One day when he was lightly arrested, he made his third suicide attempt by cutting open his elbow joint with a tin lid. He was then taken to the infirmary in Rich. When his arm was healed, he returned to Gourrama. In March 1923 Glauser had to take a truck to Colomb- Béchar and from there to Oran to “Fort Sainte-Thérèse” to undergo an examination. At the end of the month he was finally declared unfit for duty due to heart problems, dressed in civilian clothes and set out on his return trip to Europe with five francs travel money and a ticket to the Belgian border.

→ Detailed chapters :

→ Autobiographical texts from this period of life:

- 18 legionary stories . (1925–1937)

- Gourrama . (1928–1930)

“At the very bottom”: Paris, Belgium (1923–1925)

After being retired from the Foreign Legion, Glauser first traveled to Paris in April 1923 . From there he wrote to his father on April 11, 1923, explaining the new situation to him: “My dear papa, you will be amazed to suddenly receive news from Paris. […] On March 31, I was finally declared unfit for work, level 1 (without a pension, but with the right to medical treatment) because of functional heart disorders ( asystole ). […] In Oran I had to indicate where I wanted to go, and since the former Foreign Legionnaires are forbidden to stay on French soil, I gave Brussels as my new place of residence. And this because Belgium needs multilingual employees for the Belgian Congo . Because I don't want to stay in Europe, where I don't like it at all. Already the few days that I have spent here, I feel sorry for it. " In fact, Glauser initially worked as a dishwasher at the “Grand Hôtel Suisse”. In September, he was fired for being caught stealing. He then traveled to Belgium and reached Charleroi at the end of September , where, interrupted by a hospital stay as a result of a malaria relapse , he worked in a coal mine as a miner 822 meters below the ground from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. until September 1924 . Glauser again succumbed to morphine , and this was followed by his fourth suicide attempt by cutting open his wrists. He was admitted to the Charleroi City Hospital, where he worked as a carer after his recovery. On September 5, he started a room fire in a morphine delirium and was admitted to the Tournai insane asylum . In May 1925 he was returned to Switzerland to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center.

→ Detailed chapter :

→ Autobiographical texts from this period of life:

- Below. (1930)

- Between classes. (1932)

- I am a thief (1935)

- In the dark. (1936)

- Charleroi Roman fragment . (1936–1938)

- Night shelter. (1938)

"Attempts at Stabilization": Psychoanalysis and the Gardening Profession (1925–1935)

After being returned from Belgium in May 1925, Glauser was interned for the second time in the Münsingen psychiatric center . There he also met the psychiatrist Max Müller, who later carried out psychoanalysis with Glauser . In June Glauser was admitted to the Witzwil detention and labor center. There he resumed his literary work and wrote mainly short stories. On December 16, he made his fifth suicide attempt , this time by hanging, in a cell . Having regained his strength, Glauser came to the conclusion in the new year that he could not live from writing, and the desire for independence through a job reappeared in him. One profession that he then pursued for years and finally completed an annual course was that of gardening. In June 1926 he was released from Witzwil and he worked for the first time as a gardener's assistant from June 1926 to March 1927 in Liestal with Jakob Heinis. During this time he also got to know the dancer Beatrix Gutekunst and entered into a relationship with her that lasted five years. He fell back on morphine again and began forging prescriptions, leading to an arrest for stealing opium in a pharmacy in 1927. He then went back to Münsingen for rehab and began a year-long psychoanalysis with Max Müller in April. During this time he worked in the Jäcky nursery in Münsingen.

On April 1, 1928, Glauser took up his position as an auxiliary gardener in Riehen with R. Wackernagel, a son of the well-known historian Rudolf Wackernagel . In the meantime he lived with his girlfriend Beatrix Gutekunst at Güterstrasse 219 in Basel and began to work on his first novel Gourrama , in which he dealt with the formative time in the Foreign Legion. At the end of the year, he also received a loan of 1,500 Swiss francs for the legion's history from the loan fund of the Swiss Writers' Association . At the same time as he was writing, Glauser continued to work as a gardener and in September switched to the E. Müller commercial nursery in Basel, where he worked until December. This was followed by the move to Winterthur to Beatrix Gutekunst, who had opened a dance school there. At the beginning of 1929 Glauser tried in vain to lift his guardianship . In April he started working as a gardener's assistant at Kurt Ninck in Wülflingen , but fell back on morphine again. At the end of the month he was caught redeeming a counterfeit prescription and a criminal complaint was filed against him by the Winterthur district attorney. Thanks to an expert opinion by Max Müller, in which he attested Glauser's insanity , the proceedings were discontinued.

At the beginning of 1930 Glauser was back in Münsingen, where he completed the Gourrama manuscript in March . In the same month he entered the cantonal horticultural school in Oeschberg near Koppigen . This was mediated by Max Müller, who had also agreed that Glauser could obtain controlled opium without becoming a criminal. In February 1931 he finally completed the course with a diploma. He tried to continue to publish his Legionary novel, but received rejections from all publishers and so he kept afloat with feature pages and completed a follow-up analysis with Max Müller. That year, Glauser paid his aunt Amélie a two-day visit in Geneva, probably planning to write a Geneva crime thriller ( The Tea of the Three Old Ladies ), which began in October. In January 1932, Glauser rejected his gardening plans, tried to gain a foothold as a journalist and writer in Paris and moved to the French capital with Gutekunst. During this time he also got to know Georges Simenon's books and his commissioner Maigret and succumbed to the charm of the series, which was to be of crucial importance in the creation of Wachtmeister Studer . In the spring the first financial difficulties appeared and Glauser took up the opium again. At the end of May he broke off the "Paris Experiment" and visited his father in Mannheim. There Glauser again forged prescriptions, was arrested and taken into custody. Charles Pierre Glauser finally applied for lifelong internment. This was followed by another briefing in Münsingen and the separation from Beatrix Gutekunst.

In September 1933 Glauser met Berthe Bendel, who worked as a nurse in the Münsingen psychiatric institution. At that time, a completely new perspective opened up for the two of them, as Glauser had been offered a position as manager of a small estate in Angles near Chartres . Both the guardian and the prison management agreed to take the step towards mutual independence. However, this dream was shattered because Glauser got drunk in the village the day before leaving for France. As a result, the guardian and the institution refused to allow Glauser to go to France with Berthe Bendel. There was also an increasing distance between Glauser and Max Müller, which was shown, among other things, by the fact that Glauser was jeopardizing the trust of his doctor, analyst and pen friend by forging a prescription in Müller's name at the beginning of August 1933. As a result, after Glauser's missed opportunity in France and renewed falsified prescriptions in March 1934, Müller proposed a transfer to the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic . The protocol of the entry examination of Jakob Klaesi , the director of the institution at the time (and author of various dramas and poetry ), stated, among other things, for Glauser: “Moral defect. - Excessive arrogance with so little intelligence that it is just enough for a writing activity of his genre [meaning the genre of the crime novel ]. " At the end of September 1934 Glauser was transferred to the open colony "Anna Müller" near Münchenbuchsee (belonging to the clinic) . It was there that the idea of a second detective novel began to take shape after he had finished The Three Old Ladies' Tea . He was inspired by the fact that he had won first prize in the short story competition of the Schweizer Spiegel for the story “She goes about” (1934). The jury selected Glauser's text from 188 entries and increased the prize money from 300 to 500 francs in recognition of the literary quality; after almost 20 years of writing, this was the first award for Glauser.

On February 8, 1935, he wrote to his girlfriend Berthe about his new novel: “I have started a long thing that is supposed to take place in the village of Münsingen, you know, a kind of detective novel. But I don't know what will come of it. " And on March 12: “But Studer, whom you know, plays the main role. I would like to develop the man into a kind of cozy Swiss detective. Maybe it will be very funny. " In May, Glauser began typing down Schlumpf Erwin Mord . Since he had daily field work in the colony, he could only work on it three afternoons a week. By August 1935 he had written down the 21 chapters in a 198-page typescript that was to influence Glauser's life unexpectedly and to enrich the literary world of the investigators with an inimitable detective figure.

→ Detailed chapters :

→ Autobiographical texts from this period of life:

- Curriculum vitae Münsingen. (1925)

- The encounter. (1927/29)

- Untitled. (1932)

- Nurseries. (1934)

- Lamentation. (1934)

- CV Waldau. (1934)

- The Anna Müller Colony. (1935)

- June 1, 1932. (1938)

“Studer determines”: Finally success (1935–1937)

Although Glauser had been writing texts for 19 years and was able to publish them again and again (earliest German text: Ein Denker , 1916), he was still unknown at the end of 1935. He still had three years to live and in this short time his Wachtmeister-Studer novels were so successful that he suddenly became a sought-after author. In this regard, he wrote to Gotthard Schuh in 1937 : “I've been bad long enough, why shouldn't I benefit a little now when 'just around the corner there is a little sunshine for me'? And if it's even a little, I paid it, the 'sunshine'. " Success finally seemed to be there. They approached Glauser and wanted to "make" him. However, this came at a price. Glauser overwhelmed himself with new work. Under increasing pressure, he wrote to the journalist Josef Halperin in the summer of 1937, plagued by doubts: “At once again I have the impression that everything is on the brink, the path to writing detective novels doesn't seem to lead me anywhere. I want to go somewhere, as far away from Europe as possible, and I have a vague idea of a volunteer nurse. If you know anything about this, write to me. Indochina or India - you will still be able to use one somewhere. Because just being a writer - that is not possible in the long run. You lose all contact with reality. " “Studer” seemed to be increasingly a burden for Glauser, as evidenced by a letter from the same year that he wrote to a reader of his novels: “Of course, we, writers, are always happy when people give us compliments - and that's why we are happy I also say that you like the 'stud'. I feel a little like the sorcerer's apprentice , you know: the man who brings the broom to life with the sayings and then couldn't get rid of it. I brought the 'Studer' to life - and I should now, for the devil, write 'Studer novels' and would much rather write something completely different. "

The literary success with the investigator figure "Studer" began at the end of 1935. After Glauser had finished the manuscript of his first "Studer" novel Schlumpf Erwin Mord in August and had sent it to Morgarten-Verlag, nothing happened for the time being. On October 8th he fled the colony to Basel after another recipe forgery and found shelter with actor and screenwriter Charles Ferdinand Vaucher. This put Glauser on a reading evening in the "Rabenhaus" with Rudolf Jakob Humm in Zurich . The unknown author appeared in front of gathered literary friends on November 6th and read excerpts from his unpublished detective novel. Josef Halperin recalled: «The listening writers came from different directions and used to gather together, not to praise one another, but to encourage one another and to learn from one another through unwavering objective criticism. Glauser knew that and seemed to be waiting calmly for the verdict. Was it the uncertainty or the effort of reading that made him slump? [...] 'Very nice', began one, and praised the confident and bold dialect coloring of the language, the human design, the real atmosphere. It was looked at from all angles and it was agreed that this was more than one brilliant detective novel. [...] 'I'm happy about that, I'm happy about that,' said Glauser again and again, softly and warmly, with a grateful smile. " The audience agreed that a memorable event took place here. And Albin Zollinger , who was also present, remarked: "You had found a talent, a masterly talent, there was no doubt about it." The effect of Glauser's reading in the "Rabenhaus" was enormous: he finally received the confirmation from fellow writers that he had longed for. After repeated internment, he was suddenly accepted into a society of like-minded and understanding people. And he was able to make important contacts. What also stood out that evening was Glauser's voice. Halperin said again: “The man read with a somewhat singing voice and with a somewhat strange pronunciation, in which Swiss, Austrian and Imperial German sound elements mixed together, so that one involuntarily asked oneself: Where did he grow up, where had he been drifting around? The Glauser was Swiss, it was said. But while you were trying to figure out what the reason for your accent might be, you realized that you were no longer concerned with Glauser, but with an investigator Sergeant Studer. [...] You got used to the singing voice quickly. She sang with a loving monotony, so to speak, modulated very little, with a winning modesty that frowned upon the effects of the presentation and only wanted to let the substance take effect. "

After that evening Glauser returned to the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic after negotiations with his father and guardian . In view of a possible literary breakthrough, he was promised his release for the coming spring. In December Glauser started the second "Studer" novel Die Fieberkurve , the plot of which he set in the milieu of the Foreign Legion. At the end of January 1936, Schlumpf Erwin Mord was accepted by Zürcher Illustrierte (as a sequel story in eight episodes). In February Glauser began working on Matto governed , in which he had Studer investigated in the Münsingen Psychiatric Clinic. On May 18, he was released from the Waldau and it seemed that at the age of 40 Glauser should finally be given the long-awaited freedom. With his partner Berthe Bendel, he wanted to run a small farm in the hamlet of Angles near Chartres and write at the same time. As a condition for this, he had to submit his written declaration of incapacity to marry to the guardianship authorities on April 21 , including the obligation to voluntarily return to the hospital in the event of a relapse into drug addiction. On June 1, 1936, the couple reached Chartres. From there they came to the hamlet of Angles, about 15 kilometers to the east. The dream of freedom and independence gave way to various adverse circumstances over the coming months. The dilapidated house and the surrounding piece of land were in a desolate state; living was hard to think of. For the next several months, the couple tried to make a living through a combination of self-sufficiency and literary work. Glauser wrote various features articles for Swiss newspapers and magazines. In July, the Swiss Writers ' Association and the Swiss Newspaper Publishers' Association announced a competition. Glauser began with the fourth “Studer” novel Der Chinese . At the end of September, he received the notification that the Morgarten-Verlag would print Die Fieberkurve as a book if he revised the novel again, which meant additional work. At the beginning of December, Schlumpf Erwin Mord was published by Morgartenverlag as Glauser's first printed book. With this publication Glauser is often named as the “first German-speaking crime writer”. However, the detective novel Die Schattmattbauern by Carl Albert Loosli was self- published as early as 1932 (published in 1943 by the Gutenberg Book Guild).

At the beginning of January 1937 the next book appeared: Matto rules . In the meantime, however, life in Angles has increasingly become a stress test for Glauser and Bendel: Living in a ramshackle house, financial worries and the climate drained their strength. In addition, Glauser couldn't get out of being ill. A number of animals that Bendel and Glauser had raised since June 1936 also died at this time. Glauser canceled the lease and at the beginning of March 1937 drove with Berthe to the seaside in La Bernerie-en-Retz in Brittany . The two rented a holiday bungalow and in May Glauser received his first novel commission: he was supposed to write another “Studer” novel ( Die Speiche ) for the Swiss observer . However, the deadline was set for mid-June. Once again, this meant the pressure to write a print-ready text in just a few weeks. In addition, Die Fieberkurve was waiting for its seventh revision. In addition, Josef Halperin wanted to publish Glauser's legionary novel Gourrama after a revision. And last but not least, the Chinese for the writers' competition should be ready by the end of the year. Glauser reached for opium again , which meant that after the spoke had ended, he had to undergo an addiction treatment in the private clinic «Les Rives de Prangins» on Lake Geneva from July 17th to 25th . By December, The Chinese was practically over; the only thing missing was the end. However, another move was imminent: after Glauser and Bendel had given notice of their apartment, they wanted to travel to Marseille in order to cross over to Tunis . When the two reached Marseille, it became apparent that the plan with Tunis could not be implemented due to pass problems. They moved into a room in the "Hôtel de la Poste", where Glauser took turns looking after the sick Bendel and probably wrote the end of the Chinese . After Christmas, the two decided to continue their journey to Collioure . On the train, according to Glauser, the two fell asleep in their train compartment. When they woke up at Station Sète , the folder with the typescript of the competition novel, the plans and all the notes had been stolen. After the competition jury's deadline was postponed, Glauser began to rewrite the Chinese in Collioure under enormous pressure and with the help of Opium . However, he was worried that the prescriptions he got from various doctors would attract the attention of the French authorities, and so he and Bendel fled back to Switzerland.

→ Detailed chapters :

- Glauser in Angles

- Glauser and the scandal over "Matto rules"

- Glauser's loss of the "Chinese" typescript

→ Autobiographical texts from this period of life:

- A chicken yard. (1936)

- Village festival. (1936)

- Neighbours. (1937)

- Angles-Roman fragment . (1938)

«Death in Nervi»: The Last Year (1938)

When Glauser was under pressure at the beginning of 1938 to finish his Wachtmeister Studer novel Der Chinese , he resorted to drugs again. It collapsed and he was admitted to the Friedmatt psychiatric clinic in Basel from February 4 to March 17 . On February 15, he fainted during insulin shock therapy and fell with the back of his head on the bare tiles in the bathroom. The consequences were a fracture of the base of the skull and severe traumatic brain injury . The aftermath of this accident would affect Glauser until his death ten months later. On February 23, Glauser's literary efforts and sacrifices were rewarded: he and his fourth Wachtmeister Studer-Roman won first prize in the competition of the Swiss Writers' Association and won the prize money of 1,000 Swiss francs. However, the jury attached one condition to the victory: Glauser should revise the Chinese .

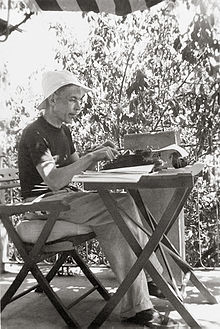

In June Glauser moved to Nervi near Genoa with Berthe Bendel . In his last six months he worked on various projects, writing down several pages a day. There was great restlessness and indecision in him, so that he began to rewrite various texts over and over again. He also had a “great Swiss novel” in mind (although he no longer began to write it); So he reported to his guardian on August 28: “Then I am constantly plagued by the plan for a Swiss novel that I want very big (big in the sense of length), and it is the first time that I try to put a plan together first before I start work. " In the midst of all this work and the convalescence of his accident in February, he tackled four new "Studer novels" , which, however, remained only fragments. As Glauser got more and more economic hardship towards the end of the year, he tried desperately to sell his unfinished “Studer” stories to various publicists and publishers, while at the same time asking for money: “We don't have a black horse anymore, our marriage is imminent the door, we should live, and I'm pretty shattered with worries. [...] Apart from you, I have no one else I can turn to. [...] I don't know what to do anymore. My God, I think you know me enough to know that I am not the kind of person who likes to curry favor with others and whine in order to get something. You know my life has not always been rosy. It's just that I'm tired now and don't know whether it's worth going on. " On December 1, Glauser also wrote to the editor Friedrich Witz : “In general, how about your trust in me? I can really promise you - even a few things that will be better than what came before - to be ready by spring '39. […] Only, I am not exaggerating, we have no more lire in our pockets. [...] Do you want something from Glauser? Much? Little? A big thing? Four Studer novels or just two or just one? Once I can work in peace, you don't have to wait for me. […] And tell me which novel you prefer: the Belgian or the Asconesian - the unknown 'Angels' novel […]. Please answer me soon and do something for the Glauser, who no longer knows what to do. And as soon as possible. " From autumn 1938 the problems in Nervi increased: The planned marriage to Berthe Bendel was delayed due to missing documents and became an endurance test; there was a lack of writing orders and the money worries grew bigger and bigger. The life situation seemed increasingly hopeless. As if Glauser had foreseen his end, he wrote to his stepmother Louise Glauser on November 29th: «I only hope one more thing: to be able to write two or three more books that are worth something (my God, detective novels are there to help you can pay for the spinach and the butter, which these vegetables urgently need in order to be edible), and then - to be able to disappear from a world as quietly as papa [Glauser's father died on November 1, 1937], which is neither very beautiful nor very is friendly. Provided that I am not unlucky enough to be interned in paradise or on another star - you just want peace, nothing else, and you don't even want to get wings and sing chorales. "

The last written testimony from Glauser is a letter to Karl Naef, President of the Swiss Writers' Association , in which he tries again to advertise one of his Studer Roman fragments : “In any case, I will allow myself to send you uncorrected manuscripts. Please think that these beginnings will change. And please understand a little the dreadful time that has fallen upon the Glauser. […] Don't be too annoyed that I'm doing 'crime fiction'. Such books are at least read - and that seems more important to me than other books whose 'value' is certainly significantly superior to mine, but whose authors do not take the trouble to be simple, to gain understanding from the people. […] If you like, I'm going to work as a gardener again. […] But what do you want: We start with detective novels to practice. The important thing will appear later. Best regards, also to Ms. Naef, from her devoted Glauser. " On the eve of the planned wedding, Glauser collapsed and died at the age of 42 in the first hours of December 8, 1938. Berthe Bendel described the last moments as follows: “The four of us had dinner so comfortably, I remember, there were herrings, those Friedel loved so much. Suddenly he takes my arm and collapses, no longer regaining consciousness. Nothing came of our forged plans to buy a house in Ticino , to take care of it and Tierli z'ha. " After his death, Glauser's sponsor Friedrich Witz wrote: “It is idle to imagine what we should have expected from Friedrich Glauser had he been granted a longer life. He wanted to write a great Swiss novel, not a detective novel, he wanted to achieve an achievement as evidence that he was a master. His wish remained unfulfilled; but we are ready, based on everything that he has left us, to award him the mastery. " Glauser found his final resting place in the Manegg cemetery in Zurich. In 1988 Peter Bichsel wrote: “I also know his grave - I visit it now and then, I don't know why - it is the first grave on the left after the entrance to the Manegg cemetery in Zurich, a small oak cross carved on it Open book with a quill pen, his name, his dates, 'Friedrich Glauser, writer, 1896–1938', the mention of his profession has always struck me as a hardship - somehow it always seemed disqualifying in this context, the short word 'writer ›.»

→ Detailed chapters :

→ Autobiographical texts:

- June in Nervi. (1938)

Glauser and the women

In the text collection "Heart Stories", the literary scholar Christa Baumberger writes: "Glauser's relationships with women can be counted on one hand." In fact, apart from his mother and the platonic friendship with the editor Martha Ringier, it was five women with whom Glauser had entered into a longer relationship. This relatively small number was also due to his unsteady résumé, which could not offer a potential partner any security. The drug addiction and constant flight were hardly bearable for a partnership in the long run. Baumberger once again: “Glauser's treatment of women reflects typical behavioral patterns for him: the conflict between flight and longing, closeness and distance. His dealings are respectful, but also show calculation. " The publicist and Glauser expert Bernhard Echte also points out this fact : "As a reader of Glauser's letters today, one knows that in them confession and calculation, deeply felt authenticity and hardened manipulation can enter into an inextricable connection." The erotic or sexual does not appear in Glauser's extensive oeuvre; at most in his initial correspondence between him and Elisabeth von Ruckteschell or Berthe Bendel. On women and sexuality, Glauser writes in an autobiographical text fragment from 1932: “Basically, opium is not a substitute for women, opium is actually only a poor consolation when, after an experience of love, I suddenly realize that I am incapable of myself to forget about it, let's say it more clearly, I stay sober, there is a shortcoming, although I am not a eunuch . But caresses are beautiful, the other thing that makes you scream so much about, it just brings an empty sadness. I'm always a little afraid of it. " Or in his confession "Morphium" (also 1932): "And opium and the poisons related to it have another effect: they suppress sexuality."

Theresia Glauser

On September 16, 1900, Glauser's mother Theresia died of appendicitis . Decades later he described his early childhood memories of his mother in the story Back then in Vienna (1938) with the following words, among other things: «I was afraid of the dark, and although my father with the long beard thought I had to be toughened up, my mother thought I was too young. Maybe that was why I missed her so much later - because she died when I was four and a half - because nobody understood this fear. " Glauser Im Dunkel (1936) was even more detailed , where he described a summer day with her, among other things: “'Hopp, little boy!' Then I push myself off the bench, it's a big jump that I dare, but my arms catch me up. It's soft when you're being held. The red dressing gown smells so fresh of cologne . I put my hand in my brown hair, hold on tight and shout: 'I can fly, mom, I can fly ...' 'Of course the boy can fly ...' says the voice. " Regarding the loss of his mother, Glauser's biographer Gerhard Saner remarks: “Glauser certainly exaggerated his mother's memory. […] How many people did not lose their mothers early: One could cope with the loss without being harmed, because perhaps he had a kind father; the other loving foster parents; the third a sensitive woman; the fourth suffered like Glauser, but he couldn't say it like Glauser, not so carefully and between the lines. " When Glauser was admitted to the "Burghölzli" psychiatric clinic in 1920 after his second suicide attempt , he associated in the young test during the examination: "Mother: dead, longing, nowhere, love, caress, crying, black." And in one of his first letters in 1933 to his future partner Berthe Bendel, he confesses: “You know, the only thing I sometimes want to complain about is that my mother died when I was 4 years old. And so all your life you staggered around looking for your mother. " Again Saner: “There was no substitute, neither with the father, nor with the two stepmothers, nor with the later women. However, Glauser looked for a replacement throughout his life. [...] There may still be a salary in the connection search for mother and home search. There are also other keywords that can be used for the search, the longing, the addiction to the mother: drugs, illness [...], suicide attempts - everywhere the desire for security, enjoyment, self-abandonment, sinking, forgetting. "

Elisabeth von Ruckteschell

After Glauser found shelter with Robert Binswanger in Ascona in 1919 , he met Elisabeth von Ruckteschell (1886–1963), who was ten years older than him, and who at that time was still in love with Bruno Goetz , who was also in Ascona and was on friendly terms with Glauser . Glauser, who knew nothing about this, was able to win Ruckteschell over with passionate letters. The liaison between the two lasted from the summer of 1919 to November 1920. The fact that Elisabeth Glauser's first great love was, as evidenced by her romantic correspondence. On September 25, 1919, for example, he wrote to her: «Do you know why you keep meeting me? Because I always have to think of you and want to drag you on the flat path of the moonbeams. When you come, little Lison, I'd like to kidnap you, all by yourself, somewhere in the Maggia Valley , for two or three days, and love you so terribly that you don't even know where your head is. That would be very nice and pleasant. " Or: «Goodbye, sweet love, I kiss your eyes and your lovely breasts. Forgive me if I cry now, I love you. " And when Glauser was already imprisoned in Bern in 1920: "I've never loved anyone as much as you."

In November 1919, Glauser and Ruckteschell moved into an empty mill near Ronco and lived there until the beginning of July 1920. In the story Ascona. Fair of the Spirit (1932), Glauser remembers that time: «We rented an old mill with a friend on the way from Ronco to Arcegno . A huge kitchen on the first floor and two rooms with the most essential furniture on the first floor. There was plenty of wood; A large, open fireplace was built into the kitchen. The mill was uninhabited for a long time. That is why all sorts of animals were quartered in it. Sometimes when we were cooking a fat grass snake crept out from under the fireplace, looked around the room ungraciously, seemed to want to protest against the disturbance and then disappeared into a crack in the wall. When I came into the kitchen at night, dormice sat with bushy tails on the boards and nibbled macaroni . Her brown eyes shone in the candlelight. The days passed calmly ... »The mill and Elisabeth also appear repeatedly in the Ascona novel fragment . At the beginning of July 1920, the romance in the mill ended abruptly: Glauser again fell victim to morphine addiction , was arrested in Bellinzona and taken to the Steigerhubel insane asylum in Bern. On July 29th, however, with the help of Ruckteschell, he managed to escape in a taxi. The police report of July 30, 1920 states, among other things: “The unknown woman who helped the Glauser escape is without a doubt identical to a certain Elisabeth von Ruckteschell, presumably residing in Zurich or Ronco, Canton Ticino. The Ruckteschell visited the Glauser several times, including Thursday the 29th of this month. Without a doubt, the appointment to escape was made on that day too. " Towards the end of the year the relationship between Glauser and Ruckteschell broke up and in spring 1921 she married Bruno Goetz.

When Glauser arrived in Charleroi after the Foreign Legion in September 1923 and was working as a handyman in a coal mine , he wrote to his former girlfriend: «I think back to it [of Ascona] like a distant, dear homeland that somehow remains a refuge in mine desolate homelessness. [...] I often think of you Lison, and even in the Legion I often believed that you would suddenly come, like in Steigerhubel, and take me with you like a fairy; but fairies have married and are happy. It's a good thing and I'm happy. Should I think that I missed my luck, as I missed pretty much everything. What do you want; the black coals rub off on the spirit. "

Emilie Raschle

The trigger for Glauser to finally join the French Foreign Legion was possibly an affair in Baden . Gerhard Saner mentions a conversation with the publisher Friedrich Witz in his Glauser biography : "Witz also told me what Glauser once said over lunch in the presence of music director Robert Blum : Mrs. Raschle was to blame for his entry into the Foreign Legion." It all started on October 2, 1920, when Glauser was released from the Burghölzli Psychiatric Clinic and found accommodation with the town clerk Hans Raschle and his wife Emilie (1889–1936), known as “Maugg”, in Baden. After the relationship with Elisabeth von Ruckteschell broke up towards the end of the year, Glauser began an affair with Hans Raschle's wife behind the back of Hans Raschle. On November 28th, Glauser wrote to Bruno Goetz : “It's pretty much the end between Ruck [Elisabeth von Ruckteschell] and me. […] I am l'amant of the woman; it is hysterical, profound, and torments me. The man is brutal. If he catches me once, he'll make me cold. That sounds like a feature novel, but it's absolutely true. " And on December 8th: «It's beautiful here now. She is fine with me and calm. Sometimes i'm happy. But then, especially when the man is there, there are tense moods that place high demands on the nerves. She loves me, I think so, at least she doesn't ask for anything. And that's a lot. It's nice to be given something again. Little intellectual, which is also redeeming. " After the turn of the year, however, Glauser turned to the 25-year-old teacher Anna Friz, who later became the wife of the politician Karl Killer , at short notice . Hans Raschle's sister said: “We, brother and sister-in-law and my friend, Glauser and I went to Carnival once . Glauser danced all night with my girlfriend, whom he already knew, and in the morning he proposed marriage to her: she should help him get out of the truck. After the first surprise, the friend immediately gave up this task. " However, Glauser continued to have a relationship with “Maugg”. On March 18, 1921, he remarked to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell: “When will I know the women? [...] After the reconciliation, things went well for a week. Then suddenly remorse on your part. She had again performed her marital duties with her husband . She wants to get rid of me. " Possibly Hans Raschle got behind his wife's affair and no longer showed any consideration for Glauser. In a letter to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center , he described the end of the abused hospitality and listed all misconduct such as theft or drug abuse; however, he did not mention the marriage fraud with a single syllable. The letter ended with the words: «When Glauser noticed that we had come across these things, he increased his doses of ether and morphine to such an extent that one fine morning in the post-delirium he pounced on my wife, who happened to be at home alone, so that she had to pull my orderly pistol at him to appease him. On the evening of the same day (it was April 1921, as far as I can remember) Glauser disappeared without saying goodbye. " The story Confession in the Night (1934) describes the triangular relationship “Glauser - Emilie Raschle - Hans Raschle” relatively bluntly .

When Glauser was already serving in the Foreign Legion in mid-May, he wrote a last letter to Emilie Raschle from Sidi bel Abbès on June 1st : «Dear Maugg, please forgive me if I write to you again. But my departure from you without saying goodbye and without thanks presses me, and I would like to say to you that I thank you for all the love and good that you have done for me. Look, you have to understand me a little. I know that I have done a lot of stupid things, that I have offended and deceived you. Very often, but it was a lot in the circumstances, in my character too. [...] I would like to ask you one more thing, Maugg. Don't think of me too badly and with too much hatred. "

Beatrix Gutekunst

After his release from the Witzwil prison and labor institution in June 1926, Glauser worked as a gardener's assistant in Liestal with Jakob Heinis. Shortly after his arrival, he met the dancer Beatrix Gutekunst (1901–2000). She was the daughter of a German art dealer family who moved from London to Bern in 1920 , where she began her training as a dancer. Glauser affectionately called her "Wolkenreh" in his letters and from April 1928 the two of them shared an apartment at Güterstrasse 219 in Basel . There they also owned an Airedale dog called "Nono", which appears several times in The Tea of the Three Old Ladies under the name "Ronny" and is described in detail. The move to Winterthur followed in December , as Gutekunst had opened a dance school there. In April 1929 Glauser was arrested on short notice for forging a prescription and criminal proceedings were initiated against the couple, which were discontinued at the end of the year. Glauser entered Münsingen again in January 1930 and then attended the horticultural nursery in Oeschberg until February 1931. In January 1932 he came up with the plan to gain a foothold in Paris as a freelance journalist and writer ; After arriving, Glauser wrote to Gertrud Müller, the wife of his former therapist Max Müller: “It was a lot of hustle and bustle until we finally landed here. […] We found a room with a kitchen in a hotel and took it until we found something else. The rent is expensive (270.– for 14 days), but everything is included, heating etc. and also a gas stove. […] Best regards from your Glauser, Hôtel au Bouquet de Montmarte (nice not?) »Shortly afterwards, the two of them moved to Rue Daguerre No.19 into an apartment with a large studio and kitchen. Glauser tried, among other things, to get access to the Palace of Justice , where he wanted to write court reports as a Paris correspondent . Although he got to know the publicist Jean Rudolf von Salis in the process , Glauser was not allowed to do so despite intensive efforts because he could not obtain the necessary press authorization. After another drug fiasco, the stay in the French capital ended at the beginning of June. In the meantime, Beatrix Gutekunst no longer saw a future with Glauser and his recurring drug relapses, internments and the recurring lack of money and separated from him. A few weeks later she married the painter Otto Tschumi and opened her own dance school in 1934 at Gerechtigkeitsgasse 44 in Bern. In the summer and autumn of the same year Gutekunst visited Glauser a few more times in the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic ; After another intensive correspondence, Glauser wanted to spend the turn of the year 1943/35 with her in Bern, which led to the final break of their friendship. Glauser had incorporated his former girlfriend in various texts after the breakup. In the story Light and Darkness (1932) she is recognizable as the friend of the narrator and in a lament for the dead (1934) the narrator clearly appears as a portrayal of Gutekunst. In the crime novel The Tea of the Three Old Ladies (1931–1934), the character of Dr. Madge Lemoyne several characteristics of the former partner. However, she has her best-known appearance in the Wachtmeister Studer novel Die Fieberkurve (1935); In the fifth chapter, Glauser sketches an unvarnished portrait of Beatrix Gutekunst: When Studer arrives at the crime scene of the second murder at Gerechtigkeitsgasse 44 in Bern, he notices a sign next to the front door with a reference to a dance school on the first floor. Shortly afterwards he lets his former girlfriend appear: “There was a lady standing in front of the door who was very thin and whose little bird's head had a pageboy hairstyle . She introduced herself as the director of the dance school in the same building and did so with a pronounced English accent. […] 'I have an observation to report,' said the lady, and to do this she twisted and turned her slender body - one involuntarily looked out for the flute of the Indian fakir, the tones of which made this cobra dance. ‹I live downstairs ...› Winding arm, the index finger pointed to the floor. » When Studer later asks her for her name, she replies: "Ms. Tschumi." Glauser's further descriptions of Gutekunst are less flattering: "Downstairs you could hear her talking with shrill screeching - in between a deep voice spoke calming words." And two pages on, Glauser puts the following words in the mouth of the tenant on the ground floor about the dance teacher: “He said that the Tschuggerei - äksküseeh: the police - could be of interest to him, the skinny Geiss - äksküseeh: the dance teacher on the first floor - had him advised to share his observations. "

Miggi Senn

Glauser was connected to Miggi Senn, who was born in 1904, from 1933 to 1935. He had already met the piano teacher in 1929 in Winterthur . Regarding their first meeting, Senn recalled, “Glauser asked her about her first impression of himself on that dance evening by Trix [Beatrix Gutekunst], probably about the performance. "Criminal physiognomy" was her answer. 'What the young girls don't say' is what he meant. Later she noticed his fine manner, but was still a little afraid of him, an insurmountable inner resistance. " This inner resistance continued when Glauser made advances to Miggi Senn in 1932 after separating from Gutekunst. Senn hesitated and everything remained in the balance. On August 4, 1933, Glauser sent her a poem from Münsingen and went on to write: “I need you very much, Mick, really. [...] You know, if the novel [ The Three Old Ladies' Tea ] is adopted, you don't have to worry about saving. Then it's enough for both of us, and during this time I can earn something again, so I'll get to 200 Swiss francs a month if I do it a little cleverly. But as I said, first I have to go somewhere to a small village, preferably to Spain , because I wouldn't want to try a big city until I'm sure of the opium. " The plan to go to Spain was not new: Glauser had already proposed it in August 1932 in a letter to his previous girlfriend Beatrix Gutekunst: “Maybe I can get enough money with my novel that I can go somewhere in Spain on Sea, as a hermit can open up ». Miggi Senn hesitated further; probably also because she was aware of the "Paris debacle" with Gutekunst. What she didn't know, however, was that Glauser was stoking two irons in the fire: Letters from the period between 1933 and 1935 prove that he was also friends with Miggi Senn and the nurse Berthe Bendel, whom he had recently met in the Münsingen psychiatric institution , maintained in parallel for two years. Both women should think they were chosen alone. For example, two months after the Spain plan with Miggi Senn, he wrote to Berthe Bendel: "I just want to hold onto you and be very, very tender with you." The last meeting between Glauser and Miggi Senn took place on October 4, 1935, in which she finally withdrew from him, whereupon he wrote to her, among other things: “The picture you make of me is certainly correct, you need it someone other than me, so we draw the consequences. [...] Farewell, my little girl, I'm very sad, but eventually that will pass too. Claus. "

Berthe Bendel

After Miggi Senn had not gotten involved with Glauser and his Spain plan, he concentrated on Berthe Bendel (1908–1986). Bernhard Echte and Manfred Papst write: “Only those who embark on a castle in the air plan with them really love them. And shortly afterwards he met a woman who wanted to dare: Berthe Bendel, a psychiatric nurse at the Münsingen clinic, twelve years younger than him. After a short time she assured Glauser that she would go with him wherever, through thick and thin. " Berthe Bendel had known Glauser since September 1933. Both of them knew that a mesalliance between a patient and a nurse had to be kept secret and they began to secretly hide messages from each other in certain books in the institution's library. In one of these first letters to Bendel, Glauser wrote: "I love you, Berthi, little one and a lot of tenderness for you, so much that it sometimes seems to me that I can't bring them all up." However, the relationship did not go unnoticed for long, there was institutional gossip and Glauser wrote to her on October 20: “Oh Berth, the people are a clean gang. A Frenchman once said, and he wasn't stupid: if you're not a misanthropist at forty, you've never loved people. […] Jutzeler naturally scorched us up. […] We have to be careful." In another letter he implored Bendel: “But if we don't get together, then I don't want to know anything more about anything, then I'll go on a wandering among the stars. And take you with me. " Or: "I've always longed for me as a woman, as you are one, so something clean and non-bourgeois and understands and all calls a. [...] And we don't want to be bullied, right? Instead, you discuss what needs to be discussed. I've always hated the people who talk so pompously about the battle of the sexes. I think that's stupid. [...] If the woman only knew how great a gift she would give if she simply gave herself. " The romance eventually led to a discussion with Director Brauchli. However, the couple stuck to the relationship and so the nurse quit her job in Münsingen at the end of 1933.

Gerhard Saner writes about Berthe Bendel and Friedrich Glauser: «Berthe wasn't the ideal woman either, she lacked a lot in her spirituality. Glauser longed for a companion like Dr. Laduner [wife of the senior physician rules in Matto ] or Wachtmeister Studer . " And so for Glauser, in addition to romance, a pragmatic aspect soon joined the relationship. On December 10, 1935, he wrote to Berthe Bendel: “You, I need the pull very much, can you send it to me soon? You will then get the other one to wash u. Patch. [...] When you send the pull, add a little chocolate and fruit, please. " In a letter to Martha Ringier dated January 4, 1936, Glauser charmingly gave his partner the attributes “a friend” and “good fellow”: “And now I come with a request. I have a friend in Basel who is still looking for a job. She doesn't care what it is, household, cooking or anything else. She is a good guy and also a qualified nurse. Do you know anything for her? " And at the end of February he asked Berthe: “And then I'm deep in the madhouse novel. You will have beautiful work there. Then you have to write it down for me. So you have to be able to type by mid-April. Remember that Berth. I promised him on May 1st. " In addition to love, Berthe Bendel seemed above all to bring the necessary stability to Glauser's life, and repeatedly helped him through creative crises and drug relapses. During the time she was Glauser's comrade, all five Wachtmeister Studer novels were written. Robert Schneider mentioned in this regard: «As the guardian of Friedrich Glauser, I can confirm that Miss Bendel played a major role in the successful work of this poet, who unfortunately died too early. This was the poet's most productive period of work. [...] Without their selfless help [...] Glauser would have ended up in sanatoriums again after a short time, as has been repeated before. " In 1934 Glauser wrote the short story Sanierung, a romantic variation on the Glauser-Bendel relationship, which was filmed in 1979 under the title "The kiss on the hand - A fairy tale from Switzerland". And with the figure of the nurse Irma Wasem in Matto reigns (1936), Glauser paid homage to his longtime partner. There, among other things, their getting to know each other is described in such a way that the patient Pieterlen (Glauser) is transferred to the group of painters and has to paint the walls in the women's B department. He meets Irma Wasem and the two fall in love. The patient Schül explains to Studer: «‹ Pieterlen had his treasure over there, and he often stood here by the window. Sometimes she came to the window and waved, the woman over there. ›»

In June 1936 the couple finally got the long-awaited freedom and they moved to Angles near Chartres . The idea of running a small farm and writing at the same time failed, however, and in March 1937 they traveled on via La Bernerie-en-Retz to Nervi in Italy, where they wanted to get married and Glauser was still writing the Studer Roman fragments . On the eve of the wedding, Glauser collapsed unexpectedly and died at the age of 42 in the first few hours of December 8, 1938. Berthe Bendel married in 1947 and, together with friends of Glauser, campaigned for Glauser's work until her death.

Martha Ringier

Manfred Papst writes about Martha Ringier: “The friendship between Glauser and Martha Ringier is one of the strangest relationships in the author's life, which is so rich in oddities. It began in the spring of 1935 [when Glauser was interned in the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic ] and lasted until Glauser's death. However, it was subject to strong fluctuations in these almost four years and in the summer of 1937 fell into a severe crisis from which it never fully recovered. " Martha Ringier (1874–1967) lived at St. Alban-Anlage 65 in Basel , was wealthy, single and understood her life in the service of literature. In 1924 she even rented an apartment to Hermann Hesse , where he began working on the Steppenwolf . She wrote poems and stories herself and worked as an editor for the family magazine Die Garbe , the Swiss animal welfare calendar, and was in charge of the Gute Schriften series . In this context, she became a maternal friend and sponsor for Glauser, and through her connections to the publishing industry, she repeatedly conveyed his texts to various newspapers and magazines and supported him financially and with gifts. The letters (in which he calls her “Maman Marthe” and usually signs “Mulet” ) that he wrote to her were often very detailed. Bernhard Echte: “At a time when he just knows how to fill a page in Berthe, Martha Ringier receives ten or more. And you don't exaggerate when you say that these letters from the early days were among the most beautiful and touching that the German-language literature of our century has to offer in this regard. "

Nevertheless, the aforementioned differences arose between the two of them, as Glauser had promised her a story for a long time and, above all, owed money. Bernhard Echte again: “A number of unspoken reservations have now piled up between Glauser and her, some of which were also fueled by Berthe. When Glauser finally came out with his allegations, Martha Ringier reacted painfully. " On August 20, 1937, he wrote an armed letter to Ringier, in which he accused her, among other things, of: “You are really terrible sometimes, maman Marthe. Do you know how often you wrote to me to remind Witz that he would send you the fee? Five times. Isn't that four times too much? [...] Don't be so scared about your money. " In addition to this letter, a draft has been preserved that Glauser never sent off and in which it becomes much clearer and, above all, more hurtful: “If you at least admitted to yourself that you are very tyrannical [...] and that you should do whatever you can fight your supremacy. The sad thing is that you don't know yourself, that you are blind to yourself. [...] The world, I would almost like to say the illusory world into which you have woven yourself, is so necessary for you to live that you would collapse if someone wanted to rob you of it. You have made a picture of yourself - and this picture must not be touched. You see yourself as the kind helper, as the one who has sacrificed herself. [...] Subconsciously, you only want one thing: to be allowed to play the leading role again, to be up to date with what Glausers receives, to play Providence. " And referring to editor Max Ras's fee (for The Spoke ), Glauser continues: “But only because I told you that Ras paid me well, like Shylock [the greedy money-lender from Shakespeare's merchant in Venice ] on his To insist on a piece of meat, I call that unworthy, forgive me the strong word. Shall I tell you why you are alone why you were always alone Because it is impossible for you to forget yourself, because your benevolence is played out and not real, because in your life you have never experienced that which actually makes life worth living: real camaraderie. And while we're at the big washing-up, I can tell you one more thing - which Berthe can confirm to you: that every time I was with you made me sick, that I never took as much opium as when I was with you. There is a kind of untruthfulness, of sentimentality, of lying to oneself that makes me sick ». Glauser's father was also aware of the differences between his son and Martha Ringier. On August 27, 1937, he wrote to him: “Finally you got rid of Miss R. too. Such visits, which try to mix everything up, are not exactly pleasant. Still, you did well not to break with her. She has done you valuable service. " This was wise advice, because around four months later Glauser needed Ringier's help more urgently than ever: After the loss of the Chinese manuscript , Glauser and Bendel found accommodation with Martha Ringier in Basel on January 8 and the necessary help to complete the new version of the Chinese to tackle. All the work took place in a specially rented room next to Ringier's apartment. For the next ten days, Glauser dictated the entire novel to Bendel and Ringier from his bed. Handwritten corrections to the typescript can be found by Glauser and both women. In a letter to Georg Gross a month later, Glauser described the work on the new version as follows: “In Basel I managed to dictate the novel, which had to be delivered by a certain date, within ten days, which was eight hours of work Dictating meant three hours a day of correcting. Then I finished it, the novel, and was done afterwards. " And Martha Ringier remembered: “It was an agonizing time, it weighed heavily on Glauser. His features were tense, his forehead mostly furrowed. He was easily irritated and sensitive. We two women tried to put every stone out of his way and often just asked ourselves with our looks: What will the result of this overexertion be? "

Create

scope

Bernhard Echte and Manfred Papst write about Glauser's work : “When Friedrich Glauser died unexpectedly on December 8, 1938, he had only just acquired a certain literary fame as a crime author: Sergeant Studer had appeared two years earlier and had achieved considerable success. However, Glauser had already written and published for more than twenty years - only hardly anyone could have foreseen the scope and importance of this work, as it was printed in many places in newspapers and magazines. " On November 13, 1915, Glauser published his first text, a review in French, in the Geneva newspaper L'Indépendence Hélvetique . 23 years later he wrote his last work with the feature section When Strangers Travel . Six of the seven novels, and around three quarters of his stories, life reports and feature sections, were written in the last eight years of his work, which lasted a little over two decades. Regarding Glauser's preferred literary genre of the story , Echte and Pope comment: «No other form suited Glauser's abilities as far as that of the story. Even his novels live far more from their atmospheric qualities than from the large arcs of the story, the construction of which for Glauser, as an open letter about a detective novel from 1937 shows, meant rather a tedious task. In contrast, his sense of the coherence of a manageable story proves to be infallible. " In addition to Glauser's poems, for which no publisher was found during his lifetime, the extensive correspondence occupies a special position. Since Glauser was incapacitated from the age of 21 until his death, hardly any other writer has been so carefully documented: In addition to his letters to his father, loved ones and friends, a number of letters were collected in administrations, guardianship authorities, in clinics and with psychoanalysts, which Glauser wrote with the same intensity with which he wrote his famous Studer crime novels. The letters are also a document of life and times that can be placed alongside his novels on a par. Bernhard Echte again: "And you don't exaggerate when you say that these early letters [to Martha Ringier] were among the most beautiful and touching that the German-language literature of our century has to offer in this regard." The following work classification mainly relates to the eleven-volume edition of the Limmat Verlag :

| Literary genre | number |

|---|---|

| Autobiographical documents from clinics (curriculum vitae, diary) | 6th |

| Correspondence | 730 |

| Dramas | 2 |

| Essays and Reviews | 11 |

| Stories , short stories , feature sections | 99 |

| French texts | 19th |

| Fragments | 20th |

| Poems | 56 |

| Novels | 7th |

On January 1, 2009, the standard protection period for Glauser's works expired. The Gutenberg-DE project then published several of its criminal cases online. His estate is in the Swiss Literary Archives , in the Robert Walser Archive (both in Bern ) and in the official custody files of the Zurich City Archives .

Writing process

Glauser's adverse living conditions usually prevented a continuous and orderly writing process. Between addiction to morphine , crimes, suicide attempts, escapes, internment, rehab and attempts at regular employment, Glauser wrote incessantly on his texts until another crash loomed. Between this series of small and large disasters, he was only able to calm down during his hospital stays and find the necessary continuity in writing. This way of working was unproblematic for short stories or feature pages, but detective novels made different literary demands. Glauser did not spend enough time thinking carefully through the actions, restructuring or rewriting them if necessary. The result was a lack of logic and inconsistencies. Mario Haldemann writes about his first detective novel Der Tee der drei alten Damen (1931): “The perspective changes constantly, the 'omniscient' narrator goes through the plot with this person, now with that person, and the reader quickly loses track of things about the tangled storylines and the abundance of staff. Glauser was well aware of this. Barely two years after completing the work, he considered converting it into a Studer novel. " Shortly before his death, Glauser wrote to his guardian Robert Schneider: “Then I am constantly plagued by the plan for a Swiss novel that I want very big (big in the sense of length), and it's the first time I try to get one first To glue the plan together before I start work. "

style

In terms of content, Glauser's texts are mostly autobiographical , in that almost without exception he processed scenes, people and experiences from his own past. The Kindler Literature Lexicon writes: "Glauser's personal experiences from that odyssey through reform schools of all kinds [...], living together with the declassed and outsiders of all kinds, were used in almost all of his novels in terms of content and atmosphere." The author Frank Göhre adds: “Whatever he wrote has to do with him. They are his experiences, the sum total of what he has experienced and suffered. " In February 1932 Glauser wrote to his friend Bruno Goetz from the Asconeser Tage : "I would like to write a new novel in which I myself do not appear in it."

Formally, Glauser developed a style that is characterized above all by atmospherically dense environmental studies . The special ability to incorporate exact observations into individual scenes could be expressed in the simple description of a room or a cloudy sky. In 1939 Friedrich Witz wrote: “The atmospheric - that is his very own area, his poetic strength. Here he stands as a champion, surpassed by no other Swiss . [...] We are faced with a phenomenon of talent that cannot be tackled with any art talk. " And further: “One word remains to be said about Glauser's way of writing. Today, when many writers laboriously experiment with capricious language and make it unnecessarily difficult for readers to understand the content they are dealing with, the uneducated reader welcomes Glauser's language twice. For Glauser, it was the most important literary duty to be understood by ordinary people. " The author Erhard Jöst comments on Glauser's writing style: “With haunting milieu studies and gripping descriptions of the socio-political situation, he manages to cast a spell over the reader. […] Glauser illuminates the dark spots that are normally deliberately excluded because they disturb the supposed idyll. " And the literary critic Hardy Ruoss recognizes in Glauser "the social critic, the storyteller and human illustrator, but also the portrayal of the densest atmospheres." In doing so, Glauser allowed himself to use a stylistic device that was widespread in the 19th century, but was rarely used in his generation: he woven Swiss-German expressions into his texts; then unexpectedly it says «Chabis» (nonsense), «squat» (sitting), «Chrachen» (hamlet), «G'schtürm» (agitation), «Grind» (head) or «What's going on? In this way of writing, his readers (especially Swiss) immediately found something very familiar and homely. And Jean Rudolf von Salis commented: "Since Gotthelf , no writer has succeeded so easily and without prejudice in inserting expressions of the dialect into the High German text."

Effect, reception