Gourrama

Gourrama is the debut novel by the Swiss author Friedrich Glauser and was written between 1928 and 1930. It is set in a remote garrison post of the French Foreign Legion in Morocco and depicts the microcosm of failed existences. Ruling alongside Matto , who treats Glauser's repeated internments in psychiatric hospitals, Gourrama is one of his most autobiographical novels, as he himself was in the Foreign Legion from 1921 to 1923. How decisive this time was for Glauser is also shown in other texts: 18 additional legionary stories and the Wachtmeister Studer crime thriller Die Fieberkurve , which is also set in the Foreign Legion, were created.

Beginning of the novel

"Only two kilometers left," said Kainz. «You can already see the tower from the post ... Now! Look! The old man's room is where the lightning flashes ... 'He held on to the stirrup and gasped because he was old. "Don't you want to ride now?" Todd asked as he wiped the sweat from his sparse whiskers. - «Well! Naa! " Kainz shook his dry head and put his handkerchief under his pith helmet. It was only new o'clock in the morning, but the sun was already hot.

content

Glauser's Legionary novel takes place from July 14, 1923 to May 1924. The 15 chapters are divided into three parts and are made up of individual collage-like episodes. The main character is the antihero corporal Lös, who can easily be recognized as Glauser himself. In the first chapter he says about himself in an autobiographical manner: «My father sent me to the Legion. [...] Even brought to the recruiting office in Strasbourg , you know, I lived in Switzerland and did a few stupid things there. Debts and such. And the Swiss wanted to put me in a job center. Dissolute lifestyle. " Stories from the Legion formed a genre of their own in the first half of the 20th century that described adventures and dangers in distant lands. Gourrama, however, practically completely dispenses with the usual ingredients of this literature and remains completely apolitical, although the Second Moroccan War was taking place at the time of his deployment . Glauser, on the other hand, does what he does best: he delivers exact descriptions of the foreign scenery; As a former Foreign Legionnaire, he knows exactly what he is writing about when he talks about pelotons , tirailleurs , oueds , halfagras , seguias (small irrigation channels), a ksar , the bled (plain), hammam , rumi , couscous , kébir (Algerian wine), tafilalet or Berber reports. Above all, Glauser is a close observer of the atmosphere and interpersonal tragedies. Gourrama's focus is therefore, completely unfamiliar for the legionary literature of the time, on realistic everyday life, living together. There is hardly any variety, there is mainly boredom and dullness. Glauser emphasized this in his autobiographical text In the African Felsental : “Of course, here too you get to know boredom; nowhere is it as horrible as it is down there. "

There is another point that Gourrama is also unfamiliar with: With a relentless openness, Glauser describes a self-contained male world that suffers from the loneliness of the individual and his painful memories of civil life. The longing for closeness, tenderness and love is omnipresent. In this regard, Lös says to the soldier Todd: "You know, we are so hungry for tenderness that a friendly word, said or received, is enough to relieve tension." Glauser also describes the consequences of this repressed sexuality: homosexuality, prostitution, rape, aggression and suicide. Commenting on same-sex in the Legion, Todd explains: “You spoke of it with a shrug, but you called things by their names. It might even occur to Capitaine Chabert to say during the report: 'Better go with a friend to the Oued behind the bushes than to an Arab woman. At least you don't risk infection! ›» And literary scholar and Glauser connoisseur Bernhard Echte remarks in Gourrama's epilogue : «Through patchouli's numerous affects, homosexuality appears in a new, unprejudiced light: as a natural expression of an indivisible, ubiquitous and constantly acute need for love . So the relationship between Todd and Schilasky - the only case of happy sexuality in the whole novel - is portrayed with a respect and sensitivity that is rarely found elsewhere, not only in Legion literature. "

Part one - everyday life

A detachement of 20 legionnaires from Algeria is on their way to the Moroccan military post in Gourrama. Adjutant Cattaneo introduces the new Sergeant Hassa to the local customs. Upon arrival, Capitaine Chabert greets the newcomers and then gives the whole company off for the rest of the day, as it is July 14th and an improvised variety show is taking place in the evening in honor of the French national holiday. After the party, Corporal Lös, who is responsible for catering in the administration, talks to the newly arrived Todd. Los and Todd are joined by Corporal Smith, Pierrard, Sergeant Sitnikoff and the gay couple Patchouli and Peschke. While Los donates wine, the soldiers tell each other the most fantastic stories of why they came to the Foreign Legion.

The next morning "old Kainz" slaughtered five sheep together with a Jew from the Ksar . Shortly afterwards, Lös has a meeting with his superior Narcisse: He persuades Lös to cheat once more in the price negotiations for today's barley delivery. Los agrees, although his guilty conscience is increasingly plaguing him as he regularly has to hand over wine and materials to other superiors. In the afternoon he meets the young woman Zeno from the nearby village, who cleans the legionnaires' laundry in the Oued . Since Los likes the girl, the two go to the dealer; he buys her a new dress, then they visit her father. After Los has smoked hash with this , he is invited to dinner. Zeno asks the legionnaire for 200 francs so that her father can buy a piece of fertile land. The latter agrees, whereupon Zeno offers himself as a woman. After the two have slept together, Lös feels bad and is afraid of a contagious disease, which is why he sneaks back into the post and numbs him with schnapps. Most soldiers there find it difficult to sleep in the heat of the night. In a barrack a card game ends in a knife fight; the group of another section leaves the accommodation to lie in the open air and talk about the ubiquitous longing for women.

The next day, Sergeant Farny asked Sergeant Sitnikoff, his young recruits, to have a Pausanker as orderly . There is a conflict between the two superiors, because Sitnikoff defends himself because it is common knowledge that Farny sexually abuses his assistants. Later that day, Capitaine Chabert appears and orders a multi-day march out. It becomes hectic, and Lös has to take care of the distribution of provisions for the whole company. He noticed again that the majority of the troops envied him for his privileged position. Before leaving, Los, who is supposed to stay in Gourrama, tells Todd about his longings and that he also meets Zeno because, compared to the prostitutes from the brothel militaire de campagne , he feels no disgust and can help her family . After the troops left the post, the company separated: instead of marching, one section had to burn lime in Atchana under Adjutant Cattaneo . There the legionnaire Schneider, who already had a fever before leaving, is feeling increasingly worse in the course of the day, and despair is growing in him. Longing for his homeland and misunderstood by his comrades, he commits suicide on the night watch.

Part two - fever

During the first day of the march, Todd and Schilasky get closer. Todd tells about his last lover, and Schilasky confesses that he is homosexual and suffers from it. When the night camp is set up in the evening, there is a duel between Todd and Sergeant Hassa, who regularly provokes the legionnaire. In the meantime, Lieutenant Mauriot Gourrama and the soldiers who stayed behind are in command . When Los comes back from Zeno, Mauriot warned him that he had left the post without permission. The supervisor also suspects that something is wrong with the food management. Los gets scared and works the whole afternoon on the bookkeeping trying to stamp out the embezzlement. When he later negotiates the purchase of sheep in the Ksar, he is drawn into an unclean business here too. Back at the post, he meets the baker Frank, who may be sick with typhus . In the hope that this incident could possibly result in a quarantine and thus distract from the accounting inconsistencies, Lös calls the legionary doctor Bergeret in Rich. He promises to ride to Gourrama the following day. Full of joy at the unexpected change, some soldiers leave the post with Lös and visit the village pub. Shortly afterwards, Lieutenant Mauriot appears, blames Los for the unauthorized exit of the troops and threatens him with a criminal investigation.

Despite Mauriot's reprimand, Narcisse persuades Los and the rest of the group to go to the military brothel , known as the "monastery". Once there, the men spread out among the prostitutes' rooms . After much hesitation, Los finally goes with a woman reluctantly. After he has paid for them, Narcisse suddenly calls everyone together because the post is looking for them. Under cover of darkness, the men sneak back into the barracks . The next day Bergeret appears, examines the patient and determines that it is not typhoid. A short time later, locals are allowed into the post so that they can sell their potatoes to the army; To make a profit, Loos has to cheat, once again, under the pressure of his superior, by taking down incorrect weight information. Again he suffers from being exploited and put under pressure by Lieutenant Mauriot. Lös leaves the post again and seeks consolation from Zeno. When he wants to go to her again two days later, he is held at the guard by his adversary Baskakoff, led back and handed over to Lieutenant Mauriot. Los is locked in solitary confinement while Mauriot tries to track down the embezzlement in the accounting department. In the meantime the rest of the company has returned to Gourrama; the march sections are badly damaged because they were attacked by a band of robbers. Capitaine Chabert, whose nerves are bare from the battle, makes Lös the scapegoat for the chaos at the post and wants to bring him before the court martial in Oran . Los, abandoned by everyone, tries to commit suicide by cutting open his elbow joint with a can lid in his cell. However, he is found, taken to the sickroom and treated by Bergeret. Sergeant Sitnikoff is later carried into the hospital room too, as he was knocked down while trying to help Pausanker get away from Farny.

Third part - dissolution

The mood in the post is simmering. Most of the men in the returned company cannot sleep as a result of the heat and the experiences of the past few days. In front of the barracks they reconstruct how the attack by the Berber gang on the legionaries took place. Schilasky is particularly upset about the injured Todd, who is currently in the infirmary in Rich. Patchouli then tells of the events of the Kalkbrenner section: After Schneider's suicide, they met two Arabs who were supposed to bring a young woman to the military brothel in Midelt ; this girl was then paid for and used by the whole section for sexual services. When Patchouli has finished his story, Kraschinsky tortures and kills Loos's dog out of sheer boredom. The whole troop suffers from a mixture of irritability, nervous tension, melancholy and aggression, which is then discharged in the murder of Lieutenant Seignac and against him mild Capitaine Chabert remarks: A revolt breaks out and can be averted at the last moment.

After these incidents, a new captain is deployed in Gourrama. He took action against rebellious soldiers with great severity, while Los was released from the Foreign Legion soon after his recovery due to health problems. When he arrives in Paris, he thinks back to the Legion with mixed feelings; Joy over the newly won freedom as a civilian alternates with the melancholy over lost comrades. When Los wants to visit Lieutenant Lartigue, who has also been dismissed, he is escorted out of the apartment in a friendly but determined manner. Los sits down on a park bench and begins to read Proust's Die wiederfinde Zeit .

Emergence

Gourrama was created between 1928 and 1930 when Glauser tried to become self-employed by working as a gardener, as he had not been able to make a living from his literary work. In these two years of writing he wanted to revive the formative times in North Africa, which is also expressed in the fact that both Marcel Proust and his novel In Search of Lost Time appear repeatedly in Gourrama . The doctor Max Müller , whom Glauser met in 1925 when he was interned for the second time in the Münsingen psychiatric center, played a decisive role in the development . Müller encouraged and supported the future writer, also established the connection to the press and thus mediated the publication of the first two legionary stories, The Little Tailor and Murder . From April 1927 onwards, Müller and Glauser also conducted a year-long psychoanalysis with five sessions a week. Glauser thanked his mentor by placing the dedication "Max Müller, the doctor, and his wife Gertrud" in front of the legionary novel.

Glauser began his first novel, the title of which was "From a small post", in mid-July 1928 when he was on vacation with his girlfriend Beatrix Gutekunst on Lake Constance . After returning from vacation, he worked again as a gardener's assistant in Basel . On August 6th he wrote to Max Müller: “I finished a novella and started a novel about the Legion. [...] Above all, I have a great desire to finish the legionary novel. I have enough material. [...] I need about a month to continue working on this novel. [...] I would like to know from you: whether you think it is worth writing the legionary story further, whether you think it is printable in this tone at all. " The fact that Gourrama was to be finished in just one month corresponded to Glauser's typical optimism of purpose, which was to be repeated in the creation of all subsequent novels. In November of the same year he received a loan of 1,500 Swiss francs for the legion's history from the loan fund of the Swiss Writers' Association .

In December 1928, Gutekunst and Glauser moved to Winterthur , where the internal pressure to cope with Gourrama increasingly weighed on him. At the beginning of April 1929, additional difficulties arose with the Werkbeleihungskasse, which made its final payment in installments dependent on Glauser revising the ending because she complained that the end of the novel was sketchily written and badly revised. The result was a relapse into morphine addiction . At the end of April Glauser was caught redeeming a forged prescription and a criminal complaint was filed against him by the Winterthur district attorney. Thanks to an expert opinion by Max Müller, in which he attested Glauser's insanity , the proceedings were discontinued. Glauser was doing badly and got into a creative crisis; on July 24th he wrote to Müller: “In addition, I no longer really know what the path is about. This whole opium story has of course warmed everything up again, the possibility of a marriage and a lifting of guardianship have of course become a long way off again. Everything is dark, I don't earn enough to be able to live on it. I've read through my novel again and, despite your assurance that it is good, I am disappointed and really consider it to be a moderate dilettante work. This without wanting to fish without compliments. I would have to work through it very, very much so that it doesn't fray, but I'm not interested enough for that, I want to write new things, I have a few plans but no time to realize them. In short, there is great chaos and great dissatisfaction with everything and everyone. " On August 1st, Müller replied, among other things: “It's not about complimenting you, but I maintain that the main thing is that the novel is really good and that you shouldn't drop it under any circumstances. Incidentally, this is not just my personal judgment, but that of everyone who has read it here or heard it from it. " Spurred on by Müller's words, Glauser went back to revising the text. At the beginning of 1930 he came again to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center for withdrawal, completed the manuscript definitively in March and then began looking for a publisher who would publish the novel.

Biographical background

Prehistory in Baden

The trigger for Glauser to finally join the Legion was possibly the affair in Baden . Gerhard Saner mentions a conversation with the publisher Friedrich Witz in his Glauser biography: "Witz also told me what Glauser once said over lunch in the presence of music director Robert Blum : Mrs. Raschle was to blame for his entry into the Foreign Legion." It all started on October 2, 1920, when Glauser was released from the Burghölzli Psychiatric Clinic and found accommodation with the town clerk Hans Raschle and his wife Emilie, known as "Maugg", in Baden . The couple wanted to give the stumbled a new chance, and in the coming weeks Raschle tried for Glauser a job at Brown, Boveri & Cie. to arrange, which however did not materialize. Instead, he completed a traineeship at the Badener Neue Freie Presse and wrote articles for the Badener Tagblatt and the NZZ . Although Glauser found a benevolent reception here and was able to bring calm to his eventful life, the whole thing ended in a catastrophe. After the relationship with Glauser's then girlfriend Elisabeth von Ruckteschell broke up towards the end of the year, he began an affair with Hans Raschle's wife behind the back of Hans Raschle. In a letter from 1925 to the Münsingen Psychiatric Center, Raschle describes the last events (without mentioning the marriage fraud) as follows: “Glauser began to drink opium on his cigarettes when he could not achieve morphine, falsified morphine recipes, even drank large amounts of ether Quanta. This went so far that he fell into real delirium at night , in which he disturbed the people sleeping next door with his noise. It then happened that he had not only sold the books of a painter, with whom he had made friends, but also books by ourselves at a local bookseller and used the money for his specific needs, that he had pumped money from our friends and had incurred debts in several shops on our behalf. When Glauser noticed that these things had occurred to him, he increased his doses of ether and morphine to such an extent that one fine morning in the post-delirium he pounced on my wife, who happened to be home alone, so that she had to pull my orderly pistol against him, to appease him. On the evening of the same day (it was April 1921, as far as I can remember) Glauser disappeared without saying goodbye. " In fact, Glauser fled across the German border to his father in Mannheim . Once there, he advised his son to join the French Foreign Legion; Glauser himself seized the opportunity to leave his recurring debacles behind and to venture a new beginning far away from everything previously known.

Foreign Legion

(the dates refer to the arrival)

How formative the time in the Foreign Legion was for Glauser is described by his long-time pen friend and benefactor Martha Ringier : “When Friedrich Glauser spoke of his stay in the Foreign Legion - it rarely happened and only during a quiet hour of the night - a painful expression always came to his face . And he usually began with the telling sentence: 'I have paid!' Then, in a matter-of-fact and impartial manner, he related some incident that woke up in him again, and his eyes were turned inward. [...] Everywhere he had proven to be unfit and anti-social. The decision to be recruited as a Foreign Legionnaire had not come, or only partially, of his own accord; but Glauser saw these years as a kind of atonement for the much suffering he had to do to his father and other people. […] It should not be overlooked, however, that a strong thirst for adventure drove him both to the Foreign Legion and later to Charleroi in the coal mines, a hunger for new people and foreign countries. [...] In Glauser, the writer who was looking for unraveled paths, who struggled for new, own expression, got excited. What he saw, experienced, suffered and felt is most condensed in his novel Gourrama . [...] So the chapter Foreign Legion in Glauser's life story has become a testimony to painful and yet so rich years. " France and North Africa, these were also Glauser's longings for distance, freedom and adventurous backdrops in exotic countries. During this time he met Oran , Sidi bel Abbès , Sebdou near Tlemcen , Géryville and Gourrama . For most of the characters in the legionary stories, real role models existed, but can hardly be determined because the Foreign Legion guaranteed anonymity. The geographical impressions, people and experiences as a soldier had strongly influenced Glauser and found their expression in Gourrama and many of his stories, even if he was mostly employed in the administration for the two years in North Africa (until he was retired due to a heart defect in March 1923) . Glauser himself said in retrospect about the experiences in the Legion: « Everything I have to say about this time and the comrades - there were some fine fellows - is in Gourrama . I didn't get any smarter or better through this adventure, but I learned a lot, a lot! "

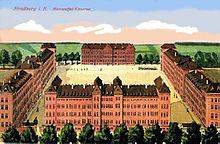

Elevation in Strasbourg

When Glauser was 25 years old, he had a number of disasters behind him: at the age of 13, he escaped from his parents' house to Bratislava , in the Glarisegg rural education home he tried to kill himself for the first time , and was expelled from Glarisegg because of one Slap in the face of his teacher. Shortly afterwards he provoked the expulsion from the Collège Calvin by criticizing a book of poems by a teacher . Then he became addicted to morphine and ran into debt. His father incapacitated him, Glauser fled and committed theft. It was the first time he was admitted to a mental hospital; Diagnosis: youthful madness . Glauser fled again, followed by his second suicide attempt, internment in the Holligen insane asylum, another escape, criminal acquisitions followed by the scandal in Baden. Gerhard Saner writes: "The father finally wanted to have peace at last, the guarantee of the most secure safekeeping." Glauser's father saw in the French Foreign Legion an opportunity to put an end to all the problems and to give up a tiresome responsibility. And Glauser himself recognized it as a new beginning, even if it was ultimately another escape, but with the pleasant result of relinquishing responsibility. In addition, he writes in the story In the African Felsental : «If the Salvation Army gives security for a new life that will unfold fully after death, from eternity to eternity, so does the Foreign Legion: It promises a new life on this earth , she gives what so many uselessly hoped for, a new name and thus a new personality. The country is far from the places where the desperate, the impatient, the dissatisfied have come to know hopelessness. The Foreign Legion relieves him of all responsibility for himself and his way of life. She gives him clothes, food, pay . She asks nothing of him except what he is only too happy to give: determination about himself. " In the summer of 1915 Glauser was already in the Swiss Army and graduated from the recruit school in Thun and Interlaken as a mountain artilleryman . He was proposed as a non-commissioned officer , but during his training he turned out to be “limp, lackluster, absolutely unable to hold his degree”. He was then dismissed from the army as unfit for service. It was therefore not easy for Glauser to join the Foreign Legion. Gerhard Saner once again: «The father had to let his personal relationships play out so that his son was accepted into the Legion at all. The first time he was raised in Neustadt / Palatinate, he was rejected, and the second in Mainz too. " After these two medically-related rejections, he was finally admitted to Strasbourg on April 29, 1921 and signed an engagement for five years of the Foreign Legion. Glauser then stayed in the Strasbourg barracks for a week . In his memoirs it says: “It was very cozy in the barracks in Strasbourg. The French soldiers, all young guys who hadn't gone through the war, admired us a little. Us: That means four German Spartakists who had struggled to flee across the border, and Lerch, an Austrian radio operator, who drove to Kehl with his last money and was hoping for a quick career in the Legion. " In May, two corporals and an adjutant from Sidi bel Abbès picked up the freshly clad recruits and traveled via Metz to Marseille . Eight days later they embarked on the steamer “Sidi Brahim” at 5:00 am for the crossing to Oran, where Glauser met Cleman, his first comrade.

Sidi bel Abbès

In mid-May 1921 Glauser arrived in Algeria and traveled with Cleman from Oran to the garrison town of Sidi bel Abbès . From there he wrote to Emilie Raschle in Baden on June 1st: «Dear Maugg, please forgive me if I write to you again. But my departure from you without saying goodbye and without thanks is pressing on me. [...] I know that I have done a lot of stupid things, that I have offended and deceived you. [...] I couldn't stand it in Switzerland any longer. […] After all, the Foreign Legion, apart from the question of military principles (perhaps the only point that troubles me internally and that I try to solve, in my own way), is a hundred times preferable to a stay in a Swiss madhouse or a correctional institution. And then I'm so tired of Europe that I rarely go out with my comrades in my free time, but visit the Arabs and try to gibberish their language a little. […] For the time being, the service is not strict, and what I see in the other companies does not make the impression that the Swiss Army made on me with its stupid drill discipline. The food is very good. Meat for lunch and dinner, only coffee and bread in the morning. Sundays dessert. We are dressed in old American uniforms, breeches and well-fitting tunics, wrap gaiters, yellow riding ties and hats. Next month we will get linen khaki uniforms and large cork helmets. […] I'm not talking about the cafard, the typical melancholy that is rampant here. It often grabs me, especially now that one is still unemployed. […] Sidi Bel-Abbès, our garrison, is a small provincial town, as big as a Bernese farming village. The European quarter is stupid and flashy, like the people who inhabit it. Only the Arabs and the little shoeshine boys, who have faithful dog eyes and are obtrusive like flies, which are my biggest nuisance, bring variety. In the Arab quarter I drink strongly sugared and flavored tea in small coffee shops, which is prepared in small cups and costs only five sous. " Glauser went to the sergeant's school for the machine gun department, where he was appointed corporal four months later. He describes his training as follows: “The service was ridiculously easy. Drill from 5.30 a.m. to 9 a.m. in front of the city walls , theory, taking apart and assembling the Mitrailleuse Hotchkiss . ‹La mitrailleuse Hotchkiss est une arme automatique fonctionnant par l'échappement de gaz.› This sentence will surely come to my mind on my deathbed when I'm desperately looking for a prayer. " In between he had to be on guard in the military prison or in his spare time he visited the “Village nègre”, the “village of cheap lust”. On June 21, Glauser joined his troops, became the captain's secretary and worked in the Fourier service. His new address was: «Machine gun company / 1. Foreign regiment ».

Sebdou

In the summer of 1921 Glauser stayed with Cleman in Algeria. The whole battalion was moved to Sebdou, around 150 kilometers southwest of Sidi bel Abbès, and billeted there. It was bored and an epidemic of desertion struck parts of the troops; Glauser himself did not take part. This was followed by a punitive transfer of the battalion to Géryville , a garrison in the middle of a high plateau at an altitude of 1,500 meters. The postponement lasted from December 17th to December 26th. First the unit marched from Sebdou to Tlemcen, then took the train via Sidi bel Abbès to Lamoricière. Then we walked along the railway line to Ain-Fecam. From there via Saïda to Bou-Ktoub again by train. Glauser describes the last part of the route from Bou-Ktoub to Géryville in a letter to his father: “From here it was 108 kilometers on foot with a full knapsack to Géryville. This knapsack is a little lighter than the Swiss one, but still uncomfortable to carry. On December 23 rd through flat and barren land. It's the Bled. Gray sand, tufts of alfagras, no water, mountains in the far distance in the south. Back there, we are told, is Géryville. We march as the last company in our battalion. We stop every fifty minutes. Almost every one of us wears tough American shoes that sore our feet. Lots of people are sick. We don't have socks, the pay isn't enough to buy them. Russian socks are made with cloth flaps. On the very first evening the whole company is a gathering of limping people. On the way there is a long stop for food: monkey meat, thin-fiber tinned meat, black coffee and uncooked macaroni , because the French army doesn't seem to know that there are field kitchens . The next day we march at 11 o'clock in the blazing sun, the uncooked food pushes our stomachs open. The boys empty their canteens. Result: diarrhea and colic . […] Departure at 4 am. Wind, snow, 48 kilometers a day ahead of us - first a stage of 30 kilometers with a cup of coffee in your stomach. - We arrive in Géryville at 4 o'clock. " Glauser built this march into the fever curve in 1935 when Sergeant Studer reached the city on a mule (on the same route as Glauser during the relocation): «Another pipe, the Béret pulled over the ears, then mounted. A rolled sleeping bag was strapped to the back of the saddle. Inside were: pajamas, two shirts, two pairs of socks, toilet kits [...] At fifty-nine you were ready to do the same as the legionnaires [...] Thank God the blizzard didn't set in until Géryville was already in sight. "

Géryville

In December 1921 Glauser and his troops reached Géryville, which was called El Bayadh after the French colonial era . In his Legionnovelle The Clairvoyant Corporal , Glauser describes the remote place on the Algerian plateau as follows: «Géryville is located on a high plateau, in the very interior of Algeria. And the plateau itself is one and a half thousand meters above the Mediterranean Sea, as evidenced by the inscription on a stone column that stands in the middle of the large barracks courtyard. The barracks itself is built in a Moorish style invented by the French , has many unmotivated horseshoe arches and a flat roof that is not used by anyone. Understandable: in winter snowstorms rage up there, as you can hardly expect them to be more violent in the Alps, and in summer the sun burns with such convincing force that none of the officers feel like getting a sunstroke up there. There are no transitional seasons like spring and autumn here in Géryville. The climate is extreme and has also forced the inhabitants into its rhythm. [...] In Géryville, the European quarter is not sharply separated from the Arab quarter. For the number of whites is too few; the town is not even a souspréfecture , only officers live there, the two larger grocery stores are run by Spanish Jews who cannot count themselves among the French. " Here too, as in Sebdou, the boredom of garrison life prevailed. Glauser reported to the troop doctor about heart problems, was transferred to the office and was often on sick leave. At the end of March 1922, twelve volunteers were wanted for Morocco . In May the selected men, including Glauser, walked across the high plateau to the next railway line. There it went on in the train. A new détachement was added at one stop . When they arrived in Colomb- Béchar , the legionaries were transported on Saurer trucks through the Sahara to Bou-Denib. From there they had to continue on foot to the abandoned Atchana post, where a section of the new company was already waiting for them. In pairs, with a loaded mule, the troops then marched to the Gourrama outpost.

Gourrama

Glauser stayed in Gourrama from May 1922 to March 13, 1923 . The Legion's outpost in southern Morocco between Bou-Denib and Midelt was next to two Berber villages , and in the distance red sandstone mountains rose up. The battalion of almost 300 men, which (as in the book) was commanded by a Capitaine Chabert, also included a mounted company with mules. The legionnaires' tasks were limited to drills , target practice and marches. In addition, if necessary, they had to protect a train with food, as gangs of robbers (Jishs) made the area unsafe. During the first medical examination, Glauser was declared unfit for marching and then came back to the administration, where he was responsible for the food and around 200 sheep and 10 cattle. However, he cheated on weights, gave unauthorized food rations and manipulated the bookkeeping with the consent of superiors. Fearing possible consequences, Glauser began to drink alcohol in excess. One day when he was under light arrest, he attempted suicide by cutting open his elbow joint with a tin lid. He was then taken to the infirmary in Rich. When his arm was healed, he returned to Gourrama. On October 16, 1922, Glauser wrote a letter to his father: “In May I left Géryville with a small detachment that was assigned to two Moroccan mounted companies. I came to the second one, which is quartered in Gourrama. I have had many adventures and fits of despair in these six months. Attempted suicide - death wanted nothing to do with me. […] Admittedly: Europe is lazy. But the putrefaction that you encounter here: the hatred from soldier to soldier, the slander, the malice, everything there is low in people, the lack of any beautiful gesture - that depresses you incredibly. " On December 4th, Glauser wrote his second and last letter from the Legion to his father from Atchana, where he had been assigned to burn lime for a month : “My dear papa! I had to go through the hell I went through to finally find the way and the surrender I was striving for ... [...] I requested my transfer to another company and the doctor supported me. [...] I am writing to you among five men with whom I share the camp and who are constantly chatting. After returning to Gourrama, I will write in more detail. For the moment, happy festivities in Mühlhausen, and think of me as I think of you. I am sending you a sonnet that I made recently. Maybe you will like it. I like it very much. " Glauser's transfer became obsolete when he was released from the Foreign Legion: in mid-March 1923 he had to take a truck to Colomb- Béchar and from there to Oran to “Fort Sainte-Thérèse” to undergo an investigation. At the end of the month he was finally declared unfit for work due to a heart problem: dressed in civilian clothes, he set off for Europe with five francs travel money and a ticket to the Belgian border.

Follow-up in Paris and Charleroi

After the retirement, Glauser first traveled to Paris . From there he wrote to his father on April 11, 1923, explaining the new situation to him: “My dear papa, you will be amazed to suddenly receive news from Paris. But I couldn't help but come here. A fortnight ago I was still working on the new bridge with a department of the mounted company very close to Bou-Denib, when suddenly the message came that I should go to Oran to be examined for unfit for service. […] On March 31, I was finally declared unfit for work, level 1 (without a pension, but with the right to medical treatment) because of functional heart disorders ( asystole ). In April I was dressed quite fashionably in civilian clothes, and I set off for Marseilles by ship like an ordinary 73 kilo package. In Oran I had to indicate where I wanted to go, and since the former Foreign Legionnaires are forbidden to stay on French soil, I have given Brussels as my new place of residence. And this because Belgium needs multilingual employees for the Belgian Congo . Because I don't want to stay in Europe, where I don't like it at all. Already the few days that I have spent here, I feel sorry for it. " In Paris, Glauser found a job as a dishwasher at the “Grand Hôtel Suisse”. In September, however, he was fired because he was caught stealing. He then traveled to Belgium and reached Charleroi at the end of September , where he worked as a miner in a coal mine until September 1924 , interrupted by a hospital stay as a result of a malaria relapse . Shortly after Glauser arrived in Charleroi, he wrote to his former girlfriend Elisabeth von Ruckteschell: “I work in the mine, 822 meters underground, night shift, from 9 in the evening to 5 in the morning. My new title: hiercheur nuit, wages 22 frs per day. […] I often think of you Lison, and even in the Legion I often believed that you would suddenly come […] and take me with you like a fairy; but fairies have married and are happy [Elisabeth von Ruckteschell had married Glauser's best friend Bruno Goetz in Florence in spring 1921 ]. It's a good thing and I'm happy. Should I think that I missed my luck, as I missed pretty much everything. What do you want; the black coals rub off on the spirit. " Glauser again succumbed to morphine and made his fourth suicide attempt by cutting open his wrists. He was admitted to the Charleroi City Hospital, where he worked as a carer after his recovery. On September 5, he started a room fire in a morphine delirium and was admitted to the Tournai insane asylum . In May 1925 he was returned to Switzerland to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center . In 1938, shortly before his death, Glauser processed his Charleroi experiences in a fragment of a Studer novel .

In 1925, Glauser noted in his résumé for his second entry in Münsingen, looking back on his time in the Legion: “I know that I have missed a lot, arbitrarily and involuntarily, that some who wanted me good suffered because of me and that I was ungrateful was, often. But I think that I've lost a lot in the two years of the Foreign Legion. The question, however, remains as to who will keep the balance between the mistakes and the subsequent suffering, and it is impossible for us to foresee the finite equilibrium that should probably arise at the end of life. "

Publications

Gourrama

When Friedrich Glauser had finished Gourrama in the spring of 1930, the vain search began for a publisher that would print the novel. The first rejection came from Engelhorn Verlag , then Orell Füssli followed . On October 24th, Grethlein Verlag wrote to Glauser: “We like to admit that Gourrama is an achievement worthy of recognition, and we would be happy if all the manuscripts submitted from Switzerland had such an originally poetic disposition and talent. Despite our praise, we cannot tell you at the moment how we are going to go to print, because on the one hand our program for the winter is over, and on the other hand the economic situation of the German-speaking book market is so catastrophic that the most beautiful books hardly find buyers. […] Maybe we can stay in touch with you about the manuscript in the near future. "

Another rejection came from Adolf Guggenbühl from Schweizer Spiegel magazine . On April 6, 1931, Glauser wrote resignedly to Max Müller: “I spoke for a long time with Guggenbühl about this novel, and he also reproached me for being so unsatisfactory. He said his reading was like being with a girl for a long time, with only kisses and caresses, without sexual satisfaction. Then you get into a state of irritation and dissatisfaction, precisely because there is no increase and no right conclusion in the novel. In other words, the novel gives the impression of impotence , at least that's how I interpreted it and I think Guggenbühl is not entirely wrong. I don't know if I have the heart to revise the novel again, I hardly think it's finished, and if I don't do it, it doesn't do much harm, it was good exercise. " Despite these words, Glauser tried to keep the Legionary novel available to publishers. However, there were further refusals from Rowohlt and Ullstein Verlag . Discouraged, Glauser gave up this time and began his second novel The Tea of the Three Old Ladies .

When Glauser met Josef Halperin at a reading in the “Rabenhaus” at the end of 1935 , he showed interest in the Gourrama manuscript, but could not find a publisher either. On February 29, 1936, Glauser wrote to him: “Dear Halperin, with the legionary novel it is vinegar. Oprecht wrote in a very friendly manner, but the Foreign Legion was not interested in publishing, the German publishers had always had bad success with legionary stories and so on and so on. It didn't surprise me. I reread the beginning and was horrified to say the least. That one was able to write such a wild German once! [...] One would have to do the whole thing differently. The beginning is far too boring, too difficult ... »In the spring of 1937, however, the situation changed unexpectedly: Halperin had joined the editorial team of the weekly magazine ABC and now wanted to print the novel. The revision began very quickly, and Glauser was asked to shorten 70 pages. Among other things, the conversation between Todd and Schilasky about homosexuality was omitted. Glauser wrote to Halperin on May 31, 1937: “Shorten ... I am a little afraid, for you too, that during the publication - and especially when you print the novel as it is - you will snatch a few subscribers become. Yes, don't forget that we are in Switzerland. I don't need to tell you how the Swiss react to homosexuality »(the passage was only reinserted in the 1997 edition of Limmat Verlag ). In March, Glauser reported to Martha Ringier in this regard: “My 'Legionsroman', my child of sorrows, is to be printed. [...] I read it again yesterday after a long time and was genuinely amazed: It is fast, reads well. [...] I'm a little afraid for Halperin that it will cause him inconvenience - the Swiss are so 'limitlessly narrow-minded' when it comes to erotic matters that there will probably be complaints. "

On August 5, 1937, the first episode of Gourrama was finally published in ABC magazine with drawings by Cornelia Forster. Glauser was satisfied, but complained about the illustrations. On August 6th he wrote to Halperin, among others: “Cornelia's groin is beautiful, but why didn't she ask me about the uniforms? The Legion has not worn this cinema uniform for seventeen years. Please tell her that we wore cork helmets (pith helmets), American khaki uniforms, breeches (riding breeches buttoned correctly on the side), calf bands up to the knee, the uniform skirt pushed into the trousers and a white, seven-finger-wide flannel bandage over it. So police hat or pith helmet. Just for God's sake not those peaked caps with the neck protection! " Unfortunately, the first publication of Gourrama remained a fragment, because on March 25, 1938, ABC with number 6 in the second year had to cease publication. Glauser biographer Gerhard Saner noted about the end of the magazine: «This, as his editor Harry Gmür gave me a good 30 years later, was indirectly to blame for the novel, because it had little plot and was not suitable for a newspaper. »

In November 1938, shortly before his death from Nervi , Glauser wrote to Alfred Graber : “Now I would like to see this novel in full print, and you can have it without further ado. If you want him. He would have appeared there at least once. […] I think you would have been successful with this topic, because - this time without making a name for yourself - I tried to make the topic completely different than usual. It contains a plot, but not an 'adventure novel', but a different one. I want to admit that I was very influenced by Proust at the time and that this will probably be noticed. " However, during his lifetime there was no longer a book edition as Glauser wished for. Half a year after Glauser's death, the sole heiress Berthe Bendel wrote to Halperin in May 1939: “I'm simply afraid that the manuscript (even if it is available in several copies) might get lost in a war. And then a wonderful work, a unique work of literature, would be irretrievably no longer to be replaced. Whereas in book form it would survive a war. " In fact, Morgarten Verlag showed interest. Friedrich Witz , who refused to be published in the Zürcher Illustrierte because of the revealing sexual descriptions, recommended the book in an opinion to the publisher in August 1939 and justified the preference of a book edition over a serial story in the newspaper as follows: The one to whom the name 'Glauser' means something and who has a certain ability to make judgments, but the newspaper comes into the hands of many people, irresponsible and youthful, above all also prejudiced, self-righteous people, and as a result would be a copy of the 'Gourrama' work Glausers sparked a storm of indignation in certain circles of the Zürcher Illustrierte readership. " The book publication by Gourrama finally took place in 1940, but by the Swiss printing and publishing house in Zurich in a first edition of 6000 copies. A second edition was printed in 1941.

Legion tales

In addition to internment in psychiatric hospitals , the Foreign Legion was probably one of the most dramatic experiences in Glauser's life. This was also reflected in some of his works: In addition to Gourrama , he brought the experiences from the Legion to life in 18 other stories. After he was brought back to Switzerland from Belgium in 1925 and taken to the Münsingen Psychiatric Center, the first two texts he had written since 1921 were Der Kleine Schneider und Mord ; both legionary stories. Glauser then adopted the former practically 1: 1 when writing Gourrama in Chapter 6. After Gourrama had not found a publisher, he changed other parts of the novel slightly from 1933 so that he could publish them as short stories in the press. So in 1933 he transferred the Gourrama episode of the murder of Lieutenant Seignac into the story The Death of the Negro , material and personnel of Chapter 7, "The March", were published in the same year as a march day in the Legion . In 1935 Glauser edited the 1st chapter "The fourteenth of July" and the 3rd chapter "Zeno" for newspapers. The text Kif from 1937 deserves special attention : the first description of a kif scene appeared in Chapter 3 of Gourrama , and then in 1931 in The Clairvoyant Corporal . Glauser became even more detailed with this autobiographical experience that he had made in Sidi bel Abbès in the second Wachtmeister Studer novel The Fever Curve , in which Wachtmeister Studer smokes hashish during his investigations in North Africa. On September 12, 1937, Glauser was asked whether he would make a short contribution to the radio series “Lands and Peoples”. He agreed, then wrote the short story Kif and came to the radio company Basel studio on November 18 to record the text. The original recording of this story is the only sound document that Friedrich Glauser has written. It was no longer broadcast during his lifetime.

| title | Emergence | First printing | Brief content |

|---|---|---|---|

| The little tailor | 1925 | The Little Bund (1925) | Description of a working day at the lime kiln , at the end of which the legionnaire Schneider committed suicide out of desperation |

| murder | 1925 | Illustrated Lucerne Chronicle (1926) | In the garrison town of Sidi bel Abbès , a recruit is murdered by a comrade so that he can desert with the stolen pay |

| The clairvoyant corporal | 1931 | The Little Bund (1931) | One in Géryville stationed corporal discovered his psychic powers and can be as an internal revolt against the battalion prevent |

| In the African rock valley | 1931 | Swiss mirror (1932) | Chronological summary and reflection of Glauser's experiences and experiences during the two years of the Foreign Legion |

| The death of the negro | 1933 | The Little Bund (1933) | Glauser's black legionary comrade Seignac is killed after he helped officer Farny escape from the Foreign Legion |

| March day in the Legion | 1933 | The Little Bund (1933) | Description of a day of marching on a mitrailleuse section in southern Morocco from the perspective of legionnaire Todd, who culminates in a fight with superior Hassa |

| The fourteenth of July | 1935 | Basler National-Zeitung (1935) | Description of a vaudeville evening improvised by legionaries in Sebdou in honor of the French national holiday |

| August 1st in the Legion | 1935 | The Bund (1935) | Instead of marching out of Sidi bel Abbès, the Swiss legionaries are given a day off to organize and celebrate their national holiday |

| Zeno | 1935 | Confession in the Night (1945) | The inconspicuous young woman Zeno, who lives in the Ksar in front of Gourrama and washes the clothes of the legionnaires, is recognized as a beauty by Sergeant Sitnikoff and married |

| Christmas in the Legion | 1935 | Swiss medium press (1935) | On the march to Géryville on December 24th, Glauser's battalion encamped in the midst of a snowstorm while the "old guy" talks about a Christmas dream |

| legion | 1936 | The Swiss Schoolboy (1937) | Report on the Foreign Legion, experiences and the Gourrama post, which Glauser wrote for a radio report for young people (the radio broadcast, however, did not take place) |

| Seppl | 1936 | Swiss animal welfare calendar (1938) | Description of a mule , at the end of which the animal saves Glauser's life in an attack and dies in the process |

| An old year | 1936 | Basler National-Zeitung (1936) | The Swiss legionnaire Baumann and the Russian Schilasky celebrate New Year's Eve in Gourrama far away from the troops with the animals of the post |

| Kuik | 1937 | Zürcher Illustrierte (1938) | A recruit in Sidi bel Abbès is murdered for his wages, after which an innocent soldier is to be tried on a court martial. A trick is used to unmask the real culprit |

| Colomb-Béchar - Oran | 1937 | Zürcher Illustrierte (1937) | When Glauser travels by train from Colomb- Béchar to Oran as a result of his retirement , his comrades steal from a fellow traveler |

| Ali | 1937 | View into the World - Yearbook of Swiss Youth (1938) | The youth narrative describes the experiences of the Moroccan Berber boy Ali, who becomes a slave after a battle and finally Marshal Lyautey acquainted |

| Kif | 1937 | Confession in the Night (1945) | Glauser wrote the autobiographical description of hashish smoking in Sidi bel Abbès for the radio series «Lands and Peoples» |

| A funeral | 1937 | Cracked Glass (1993) | A legionnaire is buried in the Gourrama Military Cemetery after he died of dysentery on a march |

The fever curve

In 1935 Friedrich Glauser finally achieved the long-awaited breakthrough with Schlumpf Erwin Mord . The readers wanted more from Wachtmeister Studer , and Friedrich Witz wrote to Glauser: "Wherever I go, I have to give information about this Glauser and I hear a song of praise for the novel without conjuring it up." Spurred on by this success, Glauser wanted to deliver a follow-up novel and came up with the idea of integrating his experiences from the Foreign Legion, which he had tried unsuccessfully to publish in the form of a novel, into the second Studer crime thriller. Jakob Studer's thoughts in the third chapter are also a glorified reminiscence of Glauser's time in the Foreign Legion: «Foreign Legion! Morocco! The longing for the distant countries and their colorfulness, which, shyly, had reported back when Father Matthias told the story, it grew in Studer's breast. Yes, in the chest! It was a strangely pulling feeling, the unknown worlds beckoned and images rose up - one dreamed of them all awake. The desert was infinitely wide, camels trotted through its golden-yellow sand, people, brown-skinned, in flowing robes, strode majestically through dazzling-white cities. […] That was luck! That was something different from the eternal report writing in the office building in z'Bärn, in the small office that smelled of dust and soil oil ... There were other smells down there - strange, unknown. " This time, Wachtmeister Studer's investigations in Die Fieberkurve actually lead far beyond the borders of Switzerland to North Africa, and hardly any other Studer novel (apart from Matto reigns ) features so many characters from Glauser's previous life. He also used scenes from his previous texts: Motifs and people such as the clairvoyant Collani and Father Matthias from The Clairvoyant Corporal appear. Géryville also revives Glauser, and the scene of the lonely Gourrama garrison post becomes the backdrop for the finale in the fever curve .

reception

When the book edition of Gourrama appeared in 1940 , the press coverage was modest. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung wrote, among other things: «A novel in the usual sense has hardly succeeded for him [Glauser]. Rather, what you have before you is a well-observed and temperamentally written, but at times somewhat broadly rolled out and in the characteristics of individual types too monotonous factual report, whereby it is pleasantly noticeable that the author renounces any thickly applied tendency in favor or to the disadvantage of the Foreign Legion. » Josef Halperin criticized “that Gourrama adheres to the characteristic lack of the first novel, that the personal dominated the literary”. It would be several decades before the novel was taken seriously by literary critics . In 1988 the writer Peter Bichsel praised : “Friedrich Glauser belongs entirely to myself. I discovered him all by myself as a youth. Back then I bought his novel Gourrama from a second-hand dealer . For me it is still one of the most important books written in Switzerland in this century because it is one of the most Swiss books; It takes place in an outstation of the Foreign Legion, the torments of legionnaires' life are written as total boredom, a little Switzerland in the Sahara. [...] The man who wrote Gourrama , the man who wrote Kuik and Kif , could not actually have been in the Foreign Legion; Boredom comes through again and again in Glauser's most terrible pictures. I read these stories 30 years ago and I have now remembered each one. " And Bernhard Echte said in the 1997 edition of the Limmat Verlag : “This makes it clear that the work was originally a highly personal development novel; At its center was a young author who - as befits a real alter ego - had to express his author's biographical, literary, psychological and metaphysical experiences on behalf of the author. In the characteristic style of a first novel, the book aimed beyond the narrated content and aimed at the whole of philosophical and ideological knowledge without false modesty. "

Theater adaptation

In 2014, the theater director and dramaturge Jonas Gillmann in Basel took Gourrama as the basis for a theater project by taking Glauser's novel Passagen and comparing it with today's situation of control, exclusion and migration.

Musical adaptation

The Glauser Quintet was founded in 2010 by Daniel R. Schneider and Markus Keller and has since interpreted Glauser's texts musically and literarily. The program of the musical readings mainly contains the “Glauser Trilogy”, consisting of the short stories Schluep , Knarrende Schuhe and Elsi - Or she goes around . In 2016, the ensemble also took on the Legionary novel by setting selected episodes under the title Gourrama - Like a wet woolen rag he stands there ; the premiere took place on September 15, 2016 in the even theater in Zurich. The Tages-Anzeiger wrote after the performance: “Now the Glauser Quintet has translated the changing moods of this book, which Peter Bichsel considers the best Swiss novel of the 20th century, into sound. It is a peculiar and idiosyncratic music, the concept of which does not reveal itself immediately, but little by little. It is increasingly lightening up - like the serious faces of the barefoot musicians Daniel R. Schneider, Marin Schumacher, Andreas Stahel, Fredi Flückiger and the reciter Markus Keller, who conjures up Friedrich Glauser in the small room of the Sogar Theater with an Alemannic pronunciation. After 70 minutes the audience was impressed by the implementation: It manages to draw a literary-musical picture in such a way that the complexity (and desperation) of the text is not leveled out. [...] Gently the Glauser quintet approaches the novel to the feelings to transform into sound: times shrill and isolated, sometimes tight and hastening straight forward - clarinets and flutes, piano and all sorts of percussion moving in arabesques a central text of Swiss literature, which conjures up the ‹discourse in the tight› not in a luxuriant way, but out of sheer necessity. At the end the room swallows the last note, just as the desert does with the legionaries: ‹The heavily loaded bast saddle of the last kitchen animal became smaller, the plain carefully swallowed the column.› »

Audio productions

In 1959, the Swiss actor and screenwriter Charles Ferdinand Vaucher adapted Gourrama as a radio play. The 92-minute version was directed by Walter Wefel, the narrator was Alfred Lohner, among others, and the music was composed by Tibor Kasics. Josef Halperin wrote about this radio version in the Schweizer Radio-Zeitung on October 24, 1959: “He [Vaucher] took out a few scenes and shortened them dramatically. The prescribed length of the game required extreme concentration. It is all the more valuable that an essential moment is captured, the Ksar , the village neighboring the legionary post, with the Arab girls Zeno, d. H. part of Gourrama's environment, the sun and wind whipped wasteland. The listener may imagine how the camp almost suffocates under the African heat during the day and freezes in the freezing cold at night. "

Translations

- Italian: Gourrama , translated by Gabriella de 'Grandi, 1990

- French: Gourrama - Un roman de la Légion étrangère , translated by Philippe Giraudon, 2002

- Latvian: Gurrama - Romans par arzemnieku legionu , translated by Austra Aumale, 2004

- Japanese: Gaijinbutai , translated by Suehiro Tanemura, 2004

literature

- du , Swiss monthly, No. 6. Conzett & Huber, Zurich 1947.

- Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser , two volumes, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main / Zurich 1981.

- Volume 1: A biography. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052534 ; NA: 1990, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 .

- Volume 2: A work history. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052683 .

- Bernhard Echte , Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 .

- Frank Göhre : Contemporary Glauser - A Portrait. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2077-X .

- Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 .

- Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 .

- Heiner Spiess, Peter Edwin Erismann (Ed.): Memories. Limmat, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-243-X .

- Christa Baumberger, Rémi Jaccard (eds.): Friedrich Glauser: Ce n'est pas très beau - An abysmal collection for the exhibition in the Strauhof. Zurich, 2016.

Web links

- Gourrama in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Friedrich Glauser's estate in the Helvetic Archives archive database of the Swiss National Library in Bern

- Friedrich Glauser's estate inventory in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 , p. 27.

- ↑ a b Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 52.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 , p. 91.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 , p. 123.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte : Afterword. In: Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 , p. 299.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 269.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 271.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A biography. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 , p. 143.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 140.

- ↑ a b du , Swiss monthly, No. 6. Conzett & Huber, Zurich 1947, p. 43.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A biography. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 , p. 148.

- ↑ a b Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 51.

- ↑ Frank Göhre: contemporary Glauser - a portrait. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2077-X , p. 30

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A biography. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 , p. 147.

- ^ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 72.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 54.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , pp. 75/76.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The fever curve. Limmat, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-85791-240-5 , p. 156.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , pp. 26/35.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , pp. 76/77.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , pp. 77/78.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 80.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 143.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 1: Matto's Puppet Theater. Limmat, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 368.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 322.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , pp. 340/341.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 175.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 611.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 613.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 669.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, p. 94.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 916.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, p. 95.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 1: Matto's Puppet Theater. Limmat, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 169.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 1: Matto's Puppet Theater. Limmat, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 182.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 26.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 232.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 288.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 97.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 101.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 135.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 140.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 155.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 175.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 275.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 13.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 51.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 53.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 90.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 94.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: Smurf Erwin Murder. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-293-20336-1 , p. 195 (afterword by Walter Obschlager)

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The fever curve. Limmat, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-85791-240-5 , p. 37/38.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, p. 97.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte: Afterword. In: Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 , p. 290.

- ↑ Peter Bichsel: Afterword. In: Friedrich Glauser: Man in Twilight . Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1988, ISBN 3-630-61814-6 , pp. 268/271.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte: Afterword. In: Friedrich Glauser: Gourrama. Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-246-4 , p. 295.

- ^ Theater and projects by Jonas Gillmann. Gourrama.

- ↑ Glauser's work reinterpreted. In: Website of the Glauser Quintet.

- ↑ Guido Kalberer: Literary concert Glauser's “Gourrama” is brought to life. In: Tages-Anzeiger , September 17, 2016.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp, Zurich 1981, p. 96.