Studer Roman fragments

The Studer Roman fragments contain the last three Wachtmeister Studer stories by the Swiss author Friedrich Glauser . They were all written in Nervi near Genoa in 1938 and remained unpublished until 1993. Glauser chose locations with an autobiographical background for all crime thrillers: in Ascona , for example, he had close contacts with artistic circles, in Charleroi , Belgium , he worked in a coal mine and in Angles near Chartres he ran a small self-catering estate.

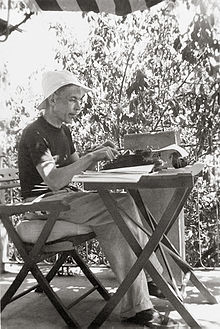

Glauser in Nervi

The last year

When Glauser was under pressure at the beginning of 1938 to finish his fourth Wachtmeister Studer novel The Chinese , he resorted to drugs again. It collapsed and he was admitted to the Friedmatt Psychiatric Clinic in Basel from February 4 to March 17 . On February 15, he fainted during insulin shock therapy and fell with the back of his head on the bare tiles in the bathroom. The consequences were a fracture of the base of the skull and severe traumatic brain injury . The aftermath of this accident would affect Glauser until his death ten months later. On July 17th he wrote to his guardian Robert Schneider: “Shortly before the decision of the jury [the Swiss Writers' Association awarded the Chinese the first prize], I fell on my head, and I was able to work on that for almost six months. Really, a couple of times I was scared - I thought I wouldn't be able to write at all. "

In June he moved to Nervi near Genoa with his partner Berthe Bendel . During this half year he worked on various projects and wrote several pages a day. There was great restlessness and indecision in Glauser, so that he began to write various texts over and over again. He also had a great Swiss novel in mind (although he no longer began to write it); On August 28, he reported to Robert Schneider: “Then I am constantly plagued by the plan for a Swiss novel that I want very big (big in the sense of length), and it is the first time that I try to put a plan together first before I start work. " On November 18, he again referred to this project when he wrote to Heinrich Gretler : “I have a big deal in the 'Gring' (excusez!)".

The Studer Roman Fragments

In the midst of all this work and the convalescence of his accident in February, Glauser tackled three new Studer cases (a fourth Studer Roman project was also set to take place in Basel, but only a few notes have survived). He invested a lot of time in different variations of the beginnings of the novel, but did not finish a single story. He had written down his ideas and notes in Italian exercise books and, based on these, constructed the crime novels on the typewriter. However, Glauser always had problems getting the plot of a novel going, as he basically worked without a plan and so repeatedly ran into dramaturgical dead ends. In 1937, for example, with regard to the spoke , he reported to his long-time pen friend and patron Martha Ringier : “It [the novel] has to be finished, of course, but it will still cost a few nasty drops of sweat. I've already started it four times and have to throw the whole beginning over again. Always the old story. You suddenly realize that you can't really do anything yet. "

It seems as if Glauser wanted to bring formative phases of his own past to life again by choosing the main locations for the planned Studer stories. Fittingly, the Ascona novel fragment (Version II) says: “By authenticity I mean that incomprehensible, indefinite that dwells between the lines, between the words and with the power of magic allows a bygone time to be reborn, with the people of that time and with the words they spoke, the thoughts they thought. I don't know whether this was successful. The reader has to play the judge. " In this fragment of the novel, Glauser tried most of the variations from the beginning (a total of 39 typescript pages). The Charleroi Roman fragment , on the other hand, had the longest execution (101 typescript pages) and the Angles Roman fragment is the shortest with 14 typescript pages.

When Glauser found himself more and more in financial distress towards the end of the year, he tried to sell his unfinished Studer novels to various publicists and publishers with desperate letters of appeal. At the beginning of October he sent Max Ras (Glauser wanted to bring out the Charleroi novel fragment in 1937 by publishing the Speiche in Schweizerischer Beobachter ) and asked for money at the same time: “We have run out of blacks, our marriage is just around the corner, we should live, and I'm pretty broken with worry. [...] Apart from you, I have no one else I can turn to. [...] I don't know what to do anymore. My God, I think you know me enough to know that I am not the kind of person who likes to curry favor with others and whine in order to get something. You know my life has not always been rosy. It's just that I'm tired now and don't know whether it's worth going on. " Ras then transferred money to Nervi. In the meantime, however, he had lost interest in Glauser's literary work, and so he returned the Charleroi novel fragment a short time later. On December 1, Glauser also wrote to the editor Friedrich Witz : “In general, how about your trust in me? I can really promise you - even a few things that will be better than what came before - to be ready by spring '39. […] Only, I am not exaggerating, we have no more lire in our pockets. [...] Do you want something from Glauser? Much? Little? A big thing? Four Studer novels or just two or just one? Once I can work in peace, you don't have to wait for me. […] And tell me which novel you prefer: the Belgian or the Asconesian - the unknown 'Angels' novel [...]. Please answer me soon and do something for the Glauser, who no longer knows what to do. And as soon as possible. "

The end

From autumn 1938 the problems in Nervi increased: The planned marriage to Berthe Bendel was delayed due to missing documents and became an endurance test; there was a lack of writing orders and the money worries grew bigger and bigger. The life situation seemed increasingly hopeless. As if Glauser had foreseen his end, he wrote to his stepmother Luisa Glauser on November 29th: «I only hope one more thing: to be able to write two or three more books that are worth something (my God, detective novels are there to help you can pay for the spinach and the butter, which these vegetables urgently need in order to be edible), and then - to be able to disappear from a world as quietly as papa [Glauser's father died on November 1, 1937], which is neither very beautiful nor very is friendly. Provided that I am not unlucky enough to be interned in paradise or on another star - you just want peace, nothing else, and you don't even want to get wings and sing chorales. "

The last written testimony from Glauser is a letter dated December 1 to Karl Naef, President of the Swiss Writers' Association , in which he tries again to advertise one of his Studer Roman fragments: “In any case, I'll take the liberty of sending you uncorrected manuscripts to be sent. Please think that these beginnings will change. And please understand a little the dreadful time that has fallen upon the Glauser. […] Don't be too annoyed that I'm doing 'crime fiction'. Such books are at least read - and that seems more important to me than other books whose 'value' is certainly significantly superior to mine, but whose authors do not take the trouble to be simple, to gain understanding from the people. […] If you like, I'm going to work as a gardener again. The only thing that would make me sad is that I wake up now and have things to say that might also interest others, perhaps show them the way. […] Maybe we are finished - we so-called artists - but we still have to say our word, even if in the chaos that covers the world like cobwebs it may wriggle like dead flies. But what do you want: We start with detective novels to practice. The important thing will appear later. Best regards, also to Ms. Naef, from her devoted Glauser. "

On the eve of the planned wedding, Glauser collapsed unexpectedly and died at the age of 42 in the first hours of December 8, 1938. After Glauser's death, Friedrich Witz wrote: «It is idle to imagine what we should have expected from Friedrich Glauser, would have been given a longer life. He wanted to write a great Swiss novel, not a detective novel, he wanted to achieve an achievement as evidence that he was a master. His wish remained unfulfilled; but we are ready, based on everything that he has left us, to award him the mastery. "

Ascona novel

content

From Ascona novel fragment eight versions have received in the estate, which detail the first two chapters describe and ready for printing. In it Glauser varies the scenes of a young man making contact with Studer and arriving at an old mill with a woman's corpse. Five versions are printed in the work edition of Limmat Verlag , which are summarized below. The most detailed table of contents relates to version III, as this appears to be the most coherent in itself.

Version I.

This takes place in 1920 and Jakob Studer is on vacation with his wife in Ticino . In the first chapter, “First Encounter”, the first-person narrator (here still with the name Niklaus Schlatter) comes to Studer's guesthouse “Mimosa” and tells of a murder that he asks the inspector to help solve (da the story takes place before the bank affair, Studer has not yet been demoted to sergeant). In the second chapter, “Memory”, the story jumps forward to the year 1934 and Niklaus Schlatter remembers the meeting with the inspector. He ponders all the people who were involved in this case at the time. [Typescript breaks off in the middle of the page]

Version II

Glauser had apparently planned this variant as a diary novel . It also comes Hugo Ball before, Glausers companion from the DADA-time in 1916 and the Ticino 1917; however, here he calls him 'Hugo Troll' . The first chapter is called «Preface» and begins in 1937. The first-person narrator (a writer) has received a package from Morocco from an unknown person. Inside is an accompanying letter (signed with the pseudonym 'Moritz Spiegel') and a diary. This tells what happened in Ticino in 1919 and how Commissioner Studer solved the case at the time. The diary was 400 pages long and has now been published in abridged form by the writer. Chapter 2, "Acquaintance", begins with the first entry in the diary from May 19, 1919. A new first-person narrator appears: He lives with his girlfriend Liso in a mill and reports how he was accompanied by two policemen to the police station is taken to Locarno. There they asked about a certain Jean Maufranc, whom the first-person narrator knew from artistic circles. [Typescript breaks off in the middle of the page]

Version III

Chapter 1 - "Interrupted Holidays": The year is 1921, Studer is 42 years old and has had stressful professional times: During the First World War and the following years, he was engaged in defending against spies and is therefore recently been promoted to commissioner. To relax, he went to Ticino with his wife Hedy at the beginning of June to spend the holidays there. The two of them stay in the "Mimosa" guesthouse above Locarno and enjoy the peace and quiet and idleness. On June 18, shortly after five in the morning, a stranger knocked on Studer's room door. The young man introduces himself as Moritz Spigl, freelance author, and explains that Baron Lorenz von Arenfurth, an acquaintance of the inspector, advised him to contact him. Still asleep, Studer Spigl follows and the two of them drink coffee in the empty dining room in silence. Then Spigl asks the investigator to follow him and explains during the following walk that he urgently needs help: Yesterday evening he came across a woman's corpse on the way home, right next to the old mill near the village of Ronco , where he lived with his girlfriend . The dead woman died from a knife stab and was treated on the advice of Spigl's friend Dr. Bone transported to the mill.

Chapter 2 - «The Mill»: When the two arrive at the disused mill in the forest, they are greeted by Spigl's friend Elisabeth von Mosegrell, dance teacher and artist. This has already phoned the Locarn police and is now waiting for Commissioner Tognola. Until he arrives, Studer takes the time to examine the woman's corpse, which is laid out on the first floor. When he looks into the face of the dead, he realizes that it is the young woman who recently also moved into a room in the “Mimosa” guesthouse. The last sentences of the fragment read: “The porter climbs the stairs, the new guest negotiates with the owner at the office desk - and speaks French. Asks whether she is allowed to live, live and eat here, even though she was seriously ill and was actually still convalescent ... A nasty illness, pneumonia, pleurisy, in the last few weeks she had even had a hemorrhage - whether it bothered anyone. Studer sees the landlady frightened ... »[The typescript breaks off in the middle of the page]

Version IV

The story begins in 1921. In the first chapter, “Evening”, Studer sits with his wife on the Piazza in Locarno. Then a stranger appears (Moritz Spigl) and asks the inspector, on the recommendation of a baron, for help. Studer then accompanies the man to a mill. A shot is fired on the way and Spigl has to be treated by Studer as a result of a grazing shot. Despite this attack, Spigl does not want to tell why he needs the inspector's help. In the second chapter, called "The mill and its surroundings", the two arrive at the mill. Studer watches a group of people sitting around a fire. You hear music from a gramophone and a woman is dancing to it. Studer introduces himself with a kiss on the hand. [Typescript breaks off at the end of the page]

Version V

Chapter 1, "Evening", differs from Version IV in that the inspector on the way to the mill tells in detail about his missions during World War I. When the two finally arrive at the mill, Spigl explains to Studer that a dead person has been found. In Chapter 2, “The Assembly”, Studer observes a group of people sitting around a fire. He sees a woman begin to dance to gramophone music. After the dance, the sergeant introduces himself to him with a kiss on the hand. [Typescript breaks off in the middle of the page]

Emergence

Glauser had been carrying around the idea of having Studer investigated in Ascona for years. The experiences he had made in Ticino from 1917 to 1920 were an important time for the young Glauser and were ideal for creating a new crime novel. The thought first appeared in July 1920; At that time he wrote to his friend Elisabeth von Ruckteschell: «Birth pains are preparing. Perhaps, peut-être, an Asconesian novel. [...] If then I don't become famous. " Another 16 years would pass before the Ascona novel came back to the fore. When his first Studer crime thriller Schlumpf Erwin Mord was accepted by Morgarten-Verlag in January 1936 , he again mentioned the Ascona novel in a letter to Ella Picard, owner of a literary agency in Zurich: "I am planning a series of Swiss crime novels, which I could probably finish within a year. [...] The hero is a Bern police sergeant (as in the 'Alten Zauberer' [the second short story for students from 1933]), a novel will be set in an asylum, one in Ascona, one in Paris. " A year later ( Matto reigns had just appeared), he took up the idea again and wrote to Martha Ringier at the end of January 1937: “I have to force myself to finish the fever chart because I would really like to write an Ascona novel in the Ich -Form where Studer is on vacation in Locarno and unravels the whole story. He's still a commissioner with the city police, the whole thing will take place shortly after the war and maybe it will be funny. Funny - let's say a different tone than the earlier ones. "

The first two versions were made five months later in June 1937 in La Bernerie . What is particularly noticeable is that these are not written authorially , as is usual with Glauser , but in the first person, which would have been a novelty for a Studer novel. Then he left the Ascona crime thriller again. In the summer of 1938 Glauser resumed his long-planned Ascona project in Nervi and wrote versions III to V; This again shows, beyond first-person narration and diary novels, the tried and tested narrative structure of the Studer crime novels. On July 15, 1938, he wrote to Friedrich Witz from Nervi: “The day before yesterday I started a new novel, which I had been studying for two weeks, and I hope it will be finished by the end of August. [...] The coming [novel], however, will be set in the Ticino village of Ascona, in the year of salvation in 1921. How should I baptize it: 'Strangers in Switzerland' or 'Studer in the South'? I neither like one nor the other - and I hope I can think of another. "

Biographical background Ascona-Roman

In the Ascona novel fragment , Glauser refers to the period between 1917 and 1920, which was very formative for him. At that time he made contact with the Dadaist scene in Zurich and with artistic circles in Ascona ; so he was unwittingly twice witness of a focal point of art history of the 20th century. Two decades after these events, Glauser wanted to process these experiences into a Studer crime thriller.

Background in Zurich: DADA

After Glauser had to leave the Collège Calvin in Geneva because of a possible expulsion from school , he moved to Zurich, passed the Matura in April 1916 and enrolled as a chemistry student at the university . At this time he got to know various artists such as Max Oppenheimer , Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp . Among them was Hugo Ball from Cabaret Voltaire , the birthplace of Dadaism. Emmy Hennings , Ball’s future wife, described her first encounter with Glauser in a letter to publisher Friedrich Witz in 1939: “I met him […] in the 'Galerie Dada', in the Sprünglihaus on Bahnhofstrasse. I was just sitting there at the cash register when Clauser came to see the storm exhibition. [….] And then he looked at the storm pictures and gradually found a pleasure in coming more often. [...] Clauser then read several times in the gallery, his own things and repostings. " In the autobiographical story Dada (1931) Glauser reports in great detail about his acquaintances and experiences with the new art form. On March 29 and April 14, 1917, Glauser took an active part in Dada soirees and describes it as follows: “But the exhibition was actually only a film, the main thing was the artistic evenings, which were given two or three times a week. And on each of these evenings, although there was little advertising, the rooms were crowded with audiences. [...] I crouch next to him [Hugo Ball at the piano] and work on a tambourine. The other Dadaists, in black jerseys, wreathed with high, expressionless masks, hop and lift their legs in time, probably grunting the words with them. The effect is staggering. The audience claps and can taste the bread that is sold during the breaks. [...] The music was no better than the language. A composer had a harmonium placed at right angles to the piano he was working on. And while he was romping around on the piano, he left his right forearm on all accessible keys of the harmonium and kicked one of the bellows with his foot. […] Busoni happened to be present when the young composer was performing his musical experiment. When the piece was over, Busoni leaned over to his companion. 'Yes', he whispered,' to stay in the style of this composition, you would actually have to double the words' da capo 'by syllable. When the listener did not understand immediately, Busoni continued: 'Well, Dada ... and so on, right?'

In Dada , Glauser also tells how he got to know the writer Jakob Christoph Heer : “My specialty was preparing language salad. My poems were German and French. I only remember one verse: 'Interlocked and devastated, sont tous les bouquins.' JC Heer happened to be present on the evening I was giving this lecture . He was so happy about the allusion to his name that the next evening he invited me to dinner in the 'Äpfelkammer' [restaurant in Zurich]. I was presented with frog legs, and Herr Heer was a good wine connoisseur. " In Version I of the Ascona Roman fragment , Glauser then incorporated this encounter in which Studer is delighted: “Artists! I'll get to know artists ... I only know one artist, so far, the old army, yes the JC, he says 'size' as if the letters were a word, I drank with him for half a night in the apple chamber ... A good potato ... »

Despite Glauser's great commitment and interest in Dadaism, the art movement ultimately stayed away from him. Emmy Hennings commented in the aforementioned letter to Friedrich Witz: "You will probably know, I think, that Clauser, although he was in Dadaist circles (after the time of Cabaret Voltaire), was not in any way a Dadaist." And Glauser himself writes about the protagonists of the Dada scene: «While the others remain very strangers to me (I always have the unpleasant impression that I cannot dare to make artistic and literary judgments, because everything that I liked is dismissed as sentimental kitsch, with a shrug of the shoulders and contemptuous puffing through the nose), Ball is the only one who seems like a quiet, older brother. [...] I don't want to be misunderstood: Far be it from me to dismiss so-called Dadaism as something semi-insane on the one hand, and speculation on snobbery on the other. For Ball at least it was a serious, I should like to say, a deep and desperate affair. Above all, do not forget the period in which this 'movement' came about: at the end of the second and the beginning of the third year of the war. As mentioned before, this dadaism was a protective measure and an escape for Ball. What use was logic, what was philosophy and ethics against the influence of the slaughterhouse that Europe had become? It was the bankruptcy of the spirit ».

Magadino and Alp Brusada

Glauser led an artist's life in Zurich instead of studying chemistry, incidentally got into debt and finally dropped out. In May 1917, the young Dadaist was advised by the Zurich official guardianship , whereupon he left for southern Switzerland; in his memoirs in Dada , he describes this phase of life as "The Flight into Ticino". There he spent from June to mid-July with Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings in Magadino and later on Alp Brusada in the Maggia Valley (in the Valle del Salto , around 7 kilometers northeast of the village of Maggia ). Glauser describes this phase of his life in the following words: «So we both went [Glauser and Ball] to Magadino one evening. Mrs. Hennings was waiting for us there with her little daughter Annemarie. Annemarie was nine years old and was drawing. I was given a large room in an old house, the walls were pale pink and the lake in front of the windows was a calm blue. The three of us were mostly silent, it was so necessary after the hustle and bustle in Zurich. We took turns cooking. But gradually the money ran out. So we decided to move to an alp at the very back of the Maggia valley. […] Our house was a shed. We slept on mountain hay. Nearby, a waterfall roared night and day. Pointed peaks surrounded our house, and the snow of the glaciers was close to us. We shared the hours of the day to use the typewriter among ourselves. […] The main foods were polenta and black coffee. Milking the goat was not easy. When we ran out of money, we parted. " Emmy Hennings also vividly remembered this time: “He was - I believe at the request of his father - in psychiatric treatment. The doctor didn't know what to do with him and was happy when we (my husband and I) took Clauser with us to Ticino. [...] We were together in Magadino for a few weeks, then on a lonely alp for a few weeks. Here I often remember that on Sundays Clauser climbed the beam of the hut and gave us sermons from this airy pulpit that were excellently worded. "

Ascona and Ronco

In 1918 Friedrich Glauser was incapacitated. This was followed by the flight to Geneva, arrest after theft, admission to the Bel-Air psychiatric clinic, diagnosis of “ dementia praecox ”. He then came to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center for the first time , where he would spend almost six years of his life. In July 1919 Glauser fled Münsingen, this time back to Ticino. There he found accommodation with Robert Binswanger in Ascona . The village at Lake Maggiore below the Monte Verita at the time was a magnet for artists' colonies , bohemians , political refugees, anarchists , pacifists and followers of different alternative movements. Glauser made the acquaintance of a number of personalities such as Bruno Goetz (who became his best friend from this time), Mary Wigman , Amadeus Barth , Marianne von Werefkin , Alexej von Jawlensky , Paula Kupka , Werner von der Schulenburg or Johannes Nohl . In his autobiographical story Ascona. Fair of the Spirit (1931) Glauser revives that time and people. A number of figures and events from that time also appear in his Ascona novel fragment . For example Schlatter (= Glauser) says in Version I: "Yes, we are a small company of artists, two painters, a graphic artist, a dancer, two writers, and then I am still there, I also write." Glauser seemed to feel very comfortable in this society of like-minded people, where intellectual exchange and culture took place. Nevertheless, he was soon drawn away again. He wrote: “I was welcomed by a group of friends that I couldn't have wished for more warmly. And yet it was barely two months before I longed for solitude again. " This longing also related to a woman: Glauser had fallen in love with Elisabeth von Ruckteschell, who was ten years his senior.

Elisabeth, called Lison, was Glauser's first great love. The passionate correspondence between the two also testifies to this. On September 25, 1919, for example, he wrote to her: «Do you know why you keep meeting me? Because I always have to think of you and want to drag you on the flat path of the moonbeams. When you come, little Lison, I'd like to kidnap you, all by yourself, somewhere in the Maggia Valley, for two or three days, and love you so terribly that you don't even know where your head is. That would be very nice and pleasant. " In November 1919, Glauser and Elisabeth moved to an empty mill near Ronco and lived there until the beginning of July 1920. In the story of Ascona , Glauser recalled this romantic time: “We rented an old mill with a friend on the way from Ronco to Arcegno . A huge kitchen on the first floor and two rooms with the most essential furniture on the first floor. There was plenty of wood; A large, open fireplace was built into the kitchen. The mill was uninhabited for a long time. That is why all sorts of animals were quartered in it. Sometimes when we were cooking a fat grass snake crept out from under the fireplace, looked around the room ungraciously, seemed to want to protest against the disturbance and then disappeared into a crack in the wall. When I came into the kitchen at night, dormice sat with bushy tails on the boards and nibbled macaroni . Her brown eyes shone in the candlelight. The days passed quietly ... »

The mill (and Elisabeth) appear again and again in the Ascona novel fragment . For example in version I: “I live again in the 'Molina', in the mill on the road that leads from Ronco to Arcegno. […] But the mill is still standing, nobody climbs up to it, thank God it is secluded… Dormice live in it together with me and eat my rice and macaroni. » And with regard to the writing activity in the mill, Glauser bluntly uses his own biography for the protagonist in Version III: “Wanted to study, started in Zurich ... chemistry, yes. But my father couldn't send me any more money, so I tried to get by with private lessons. I almost starved to death. Then I wrote articles, little stories, something longer, a Geneva novel [Glauser is referring to his novella Der Heide from 1917/1920], a magazine accepted it and paid me well. "

At the beginning of July 1920, the romance in the mill ended abruptly: Glauser again fell victim to morphine addiction , was arrested in Bellinzona and taken to the Steigerhubel insane asylum in Bern. On July 29th, however, with the help of Elisabeth, he managed to escape by taxi. The police report of July 30, 1920 states, among other things: “The unknown woman who helped the Glauser escape is without a doubt identical to a certain Elisabeth von Ruckteschell, presumably residing in Zurich or Ronco, Canton Ticino. The Ruckteschell visited the Glauser several times, including Thursday the 29th ds. Without a doubt, the appointment to escape was made on that day too. " What Glauser did not know about was that the sergeant's head of operations in this matter was called Studer. After this escape he found a place to stay with the Raschle family in Baden for a short time before joining the Foreign Legion.

Elisabeth von Ruckteschell married his friend Bruno Goetz shortly after Glauser's separation in spring 1921. Glauser maintained contact with both of them in the following years. He closes his memories of the time in Ticino with the following words: “This is how my time in Ascones ended. I learned a lot there, less from the people, although they too have influenced me. Perhaps the most important thing I learned there was the insight that one should not overestimate intellectual products. And especially yourself as the creator of these mental products. [...] We have no right to pride ourselves on our abilities. And vanity is unfortunately very common. "

Comic

On May 24th, 1996 the magazine Cash wrote : «The big hype surrounding Friedrich Glauser (1896–1938) is over: his 100th birthday was dutifully celebrated on February 4th, 1996. But a more exciting search for clues has only just begun: The Glauserians still have a few trump cards up their sleeves. " Meant was, among other things, Hannes Binder's latest comic adaptation: After Glauser's Chinese as a comic (1988), Die Speiche (under the title "Krock & Co." , 1990) and Knarrende Schuhe (1992), the unfinished Ascona material now followed the title of Wachtmeister Studer in Ticino . In the foreword of the graphic novel , crime novelist Peter Zeindler writes : “There is this fragment of a novel in which Glauser sends his hero to Ticino, places him near Monte Verita, in the Arcegno mill, and forgets there. It may have been the idea that Studer is still sitting there like King Barbarossa, that his mustache grows through the table and that after Glauser's death he is waiting for someone to redeem him. And at the same time, this gives Binder the tempting opportunity to [...] start a rescue operation and continue to think through the story initiated by Glauser, to draw, on his own. "

Binder takes Glauser's basic ideas and varies the plot so that the story ends in a circular connection : When Studer and his wife are on vacation in Ticino, he witnesses a swimming accident. Shortly afterwards, a stranger contacts him who introduces himself as Friedrich Glauser and can use photos to prove that the drowned woman was in fact murdered. Glauser, who lives in a mill near Arcegno, asks the commissioner for help in solving the crime. When Studer saw a film about expressive dance of the 1930s during the Locarno Film Festival that evening , he recognized the dead woman in a dancer on the screen and began to investigate. His first visit is to the villa of the famous guru "Ernesto", whose lover the murdered woman was. A short time later, the body of «Ernesto's» bodyguard is discovered next to Glauser's mill. Studer penetrates the empty mill and finds the photo of the dead dancer there; on the back it says: "The dream dancer Friedel from his dancing muse." Shortly afterwards he discovers an old typewriter with a sheet of paper in it. He begins to read and notices that the text describes Studer's past hours exactly. He also finds a note in the trash that lists the entire plot of the case in keywords.

In a total of 73 panels , Binder brings Glauser's time in Ticino back to life in detail by integrating, for example, the Piazza Grande, the Locarno Film Festival, the Maggia Valley , the Monte Verità or the Centovalli Railway into the criminal case. In addition to Glauser himself, well-known personalities also appear in the comic: For example, the curator Harald Szeemann or the crime author and resident of Ticino, Patricia Highsmith, sit in a grotto . Even Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman can be found in Wachtmeister Studer in Ticino . And last but not least, Hannes Binder himself, by offering Studer and his wife a seat at his table in a restaurant. Peter Zeindler once again on the freedom of drawing: “Binder gives his old friend [Studer] a lot of space, no longer forces his cumbersome mind into the comic grid, but lets him wander, even sniff, and search in his favorite magical locations. And he even helps Studer meet his creator Glauser at a summer swimming pool, who asks him for help in one case. [...] Together, Studer and Glauser Binder elicited a picture story, a series of southern miniatures, of visionary landscapes, of confrontations that are so impressive because, for the first time in this troika , the draftsman does not only have the serving, interpretive function had to or wanted to take over, but can now give in to his own fantasies and longings. "

In 2002, Hannes Binder gave Studer another appearance in Ticino. In Version IV of the Ascona Roman fragment , the passage when Studer comes to Mühle at night and observes people around the fire reads: “A scratchy noise. Violins began to sing, very softly. It was a tune the inspector had heard before, he couldn't remember where. It was a strange melody, and in the silence of the night it seemed to wake up unknown creatures that one usually only found in fairy tales. " Based on the lines of this fragment, Binder called his new comic "A melody that the inspector had heard before ..." In this dream-like plot, personalities like Hannah Arendt and Max Frisch , who also have a close connection to Ticino, gather next to Glauser and his sergeant had.

Charleroi novel

content

From Charleroi novel fragment , two larger versions have received in the estate. Glauser varied the escape of a defendant and a murder in the hospital and mining environment .

Version I.

Version I of the Charleroi thriller is the longest of all the novel fragments. However, Glauser has replaced Studer with a new investigator: Commissioner Roquelair from Charleroi. The locations and staff, however, are similar to Version II, in which Jakob Studer begins to solve the murder case.

Version II

Chapter 1 - “Swiss Abroad”: April 1923, Charleroi mining town in Belgium . The prisoner Ignaz Kohlhepp was brought to the civil hospital for an operation. Shortly after the operation, the policeman Coster, who is supposed to guard Kohlhepp, is anesthetized by a sleeping pill in his coffee, so that the prisoner can escape. The next morning, Gustave Melon, commissioner of the Charleroi city police, gathered all persons who could help clarify the disappearance for an interrogation in the conference room of the hospital: Director Cromelinckh, senior physician Dr. Bellot, the surgeon Dr. Jean Deton, the head nurse Jeanne Pestiaux and her deputy Vera Schukany. Some of the sisters and the nurse and night watchman Frédéric Mortaval (first-person narrator) also take part. The survey shows, among other things, that Kohlhepp and Mortaval are both Swiss; For this reason Melon asks the night watchman to come with him to breakfast to meet one of his compatriots. Before the two leave the hospital, the inspector notices that Mortaval is keeping Sedol ampoules [drug containing morphine] in his cigarette case, which could possibly have been used to put Private Coster to sleep.

Chapter 2 - "A Bern inspector waits, discusses, has breakfast and then lets me talk about it": On the way to the restaurant, the inspector explains to Mortaval about the relationships between hospital staff. When Melon arrives at the inn, he introduces Commissioner Studer from the Bern city police to the caretaker; he recently took part in a criminalist congress in Brussels and then visited his friend Melon in Charleroi. Since Swiss citizens are involved in the current case, Melon has asked his police colleague for help. For Studer, the Kohlhepp case is explained again during the following breakfast: The coal mine worker Ignaz Kohlhepp has been accused by his landlady Mélanie Vandevelde of stealing 20 francs. Although Kohlhepp has denied the act, he was taken into custody by the police. He then attempted suicide in the cell by swallowing a broken spoon. He was then admitted to the hospital in an emergency, where he was able to escape after the operation. When Melon finishes his statements, Private Coster comes into the restaurant and reports a murder: Karen Deton, wife of Dr. Deton was found with his throat cut in the armchair of her apartment. Melon has to go to the scene immediately. Studer then has a detailed conversation with Mortaval. While he talks about his difficult past (Foreign Legion, coal mine work, malaria relapse, love for the nurse Juliette Vanrossom, suicide attempt), he finds confidence in the Bern investigator. Studer would like to include Mortaval in the investigation.

Chapter 3 - “One meeting, two houses and the Swiss women in the hospital”: After breakfast, Studer and Mortaval make their way to Ms. Vandevelde's workers' pension to interview Kohlhepp's former landlady. It turns out that the person you are looking for can possibly be found in the Cabaret «Gambrinus», as he has had contact with the singer and dancer Marie Haarlem. During lunch, Studer assigns Mortaval to two assignments: In the afternoon he should go back to Ms. Vandevelde to find out more and later visit the Gambrinus to possibly find Marie Haarlem.

Chapter 4 - "A visit - and another": After his visit to the workers' pension, Mortaval Studer tells what he found out about Ms. Vandevelde: Kohlhepp had been a tenant in the pension since February and was often seen talking to an unknown person Man went for a walk. It also seems strange that Kohlhepp was seen repeatedly with a shovel in the basement of the house. Rumor has it that shortly before the Germans invaded during the war, the previous owner of the house had buried his gold coins before he had to flee.

Chapter 5 - «Gambrinus»: In the evening Mortaval visits the Casino «Gambrinus» in search of Marie Haarlem. This appears on stage after the break. Mortaval invites the singer to champagne after the performance with Studer's money. When he asks her about the murder of Karen Deton, Marie tenses up and evades further questions. Nevertheless, she begins to talk about Kohlhepp. A man in a tuxedo appears and waves the singer over. Mortaval leaves the bar to report to Commissioner Studer, who is meanwhile waiting in the hospital. [The typescript breaks off in the middle of the page]

Emergence

When Glauser was in Angles in 1936, a letter to Martha Ringier first hinted at the Charleroi material. So he wrote to her on October 20th, referring to his story Im Dunkel : "It is possible that it will strike, I hope so, then you can have another booklet with Charleroi Hospital." Since the hoped-for success was denied in the dark , Glauser did not pursue the idea with Charleroi any further. Two years later, however, when Max Ras from the Swiss observer showed renewed interest in the material, Glauser resumed work on it in the summer of 1938. On October 4th he sent the beginnings of the two Charleroi versions from Nervi to Ras, accompanied by a letter of appeal in which he wrote, among other things: “At the time you wanted a sequel to Im Dunkel , which you liked better than my Studer novel The spoke . I've been tinkering with this sequel for two months now, because it's supposed to be good for you. And now I could finish it, well, as you can see from the enclosed manuscripts, if I have at least another month of absolute peace. […] So if you like one or the other beginning of the story, please send me CHF 300 in an express letter. I know it's asking a lot. […] But if you find that either one or the other - already worked through - version (1st chapter: Swiss abroad) pleases, then you can trust me and help me. If you tell me which version you like best, I'll finish this. " In the meantime, however, Ras had lost interest in Glauser's texts. However, on October 7th he had 500 lire transferred to Nervi, to which the editor Dr. Koenig wrote: "Would you please consider the amount as support in your current emergency and not as a fee payment." On November 4th, the typescripts were returned, for which Dr. Koenig commented: «Since Mr Ras is absent from Basel, we are not in a position to answer your questions. To the best of our knowledge, our publishing management has no intention of purchasing another novel from you. "

The fact that Ras (after he had published The Speiche ) was no longer interested in Glauser's literary work may also be due to the fact that the Charleroi novel fragments were not able to convince. Compared to the other two Studer projects from 1938, the Charleroi fragment seems half- baked: Many scenes seem too long and there is often no discernible reference to the criminal act, which barely flows. And by gathering so many Swiss people in Charleroi (several nurses, Kohlhepp, Mortaval, the pastor, Marie Haarlem), he is straining chance too badly. The Glauser biographer Gerhard Saner asks in this regard, perhaps the Charleroi novel fragment is a: «… a consequence of Glauser's skull fracture and concussion in Friedmatt that became a prose? The reference to the author's physical condition is not entirely inappropriate, let's just remember the work disturbances mentioned at the beginning after the Friedmatt cure. "

Biographical background of the Charleroi novel

When Friedrich Glauser was retired from the Foreign Legion in the spring of 1923 because of a heart defect , he first traveled to Paris and worked there as a dishwasher at the “Grand Hôtel Suisse”. He was fired in September for being caught stealing. He then traveled to Belgium and reached Charleroi at the end of September. He stayed there for a year until September 1924. During this time he worked in a coal mine as a miner , interrupted by a stay in hospital as a result of a malaria relapse . Shortly after Glauser arrived in Charleroi, he wrote to his former girlfriend Elisabeth von Ruckteschell: “I think back to it [to Ascona] like a dear far away home that somehow remains a refuge in my desolate homelessness. [...] I work in the pit, 822 meters below the ground, night shift, from 9 in the evening to 5 in the morning. My new title: hiercheur nuit, wages 22 frs per day. [...] I often think of you Lison, and even in the Legion I often believed that you would suddenly come, like in Steigerhubel, and take me with you like a fairy; but fairies have married and are happy [Elisabeth von Ruckteschell had married Glauser's best friend Bruno Goetz in Florence in spring 1921 ]. It's a good thing and I'm happy. Should I think that I missed my luck, as I missed pretty much everything. What do you want; the black coals rub off on the spirit. " Glauser again succumbed to morphine and it was followed by his fourth suicide attempt by cutting open his wrists. He was admitted to the Charleroi City Hospital, where he worked as a carer after his recovery. On September 5th he started a room fire in a morphine delirium and was admitted to the Tournai insane asylum . In May 1925 he was returned to Switzerland to the Münsingen Psychiatry Center .

Glauser wanted to design the scenes and characters from back then in detail in the planned novel. The Charleroi novel fragment is probably the most autobiographical of the three. This can already be seen in the fact that Glauser has the crime story told in a first-person perspective through the character of Frédéric Mortaval, who is more recognizable than Friedrich Glauser in any other story. For example, when Mortaval introduces himself to Commissioner Studer, the biographical information corresponds to practically all of Glauser's own life: “'Mortaval Frédéric,' I said obediently. ‹Born on March 15, 1896 in Ins. Parentless. Previous conviction in 1917. Eight months in Regensdorf for burglary. Trained gardener. Afterwards a job in Baden. It came about because I had a criminal record, which is why I joined the Foreign Legion in Strasbourg in April 1920. Two years later, in April 1922, I was literally discharged in Oran because of malaria and heart disease. Hospital in Paris, then casserolier . Afterwards I went to Brussels to find a job in the Belgian Congo. But they could only need skilled workers - not gardeners. The employment office sent me to Charleroi because henchmen were needed in the coal mines. Two months night shift. Then a fever attack. Then work over the earth. Together with a fat man I had to fill sacks for the pit horses with oats and chaff. ›» Glauser also knew most of the characters in the Charleroi fragment from his year as a miner and nurse in the hospital, which he had already mentioned in the short stories The Queen's Visit ( 1929), Between the Classes (1932) and In the Dark (1936).

Angles novel

content

From Angles novel fragment , three versions have received in the estate, each of which detail the beginning of the first chapter and describe druckreif. In it Glauser varies Studer's assistance to an innocent accused.

Version I.

Chapter 1 - "The bearded man over the cathedral portal": Winter 1923, Jakob Studer is still a commissioner at the Bern city police and is working in his office when police captain Lüdi comes in and presents a letter from France from his nephew Albert. He lives in Angles, a hamlet around 15 kilometers east of Chartres, and runs a small estate there. In the letter, Lüdi asks his uncle for help, as he is currently imprisoned in Chartres and is charged with killing his neighbor, the wealthy cattle dealer Fernand. The gendarmerie found a large amount of money and a blood-soaked apron under Albert's bed. The French court faces the death penalty for robbery and murder . The work colleague Lüdi asks Studer for help to look into the matter on site. After a moment's consideration, the commissioner agrees, takes a week's vacation and then travels to France to help a Swiss citizen abroad. When he arrives in Paris, Studer first meets with his friend Inspector Madelin. However, he cannot help the Bern investigator, as the evidence against Albert Lüdi is too overwhelming. Madelin advises Studer to unofficially contact the examining magistrate of Chartres. Studer goes back to the hotel and decides to continue to Chartres the next morning. [The typescript breaks off at the end of the page]

Version II

Chapter 1 - “Cinema in Summer”: On a hot summer's day in Zurich, Studer is waiting for his train to Bern. Until he leaves, he spends his time in the cinema and ends up in an extremely kitschy Schmonzette . When the lights in the hall come on again, Studer sees his nephew Karl Segesser, the unlucky one of the relatives. However, a year ago he finally got lucky by finding a job in France: a bank director from Paris who owned a small estate near Chartres was looking for an administrator. Karl got the job and traveled to Angles with his wife. Studer invites his nephew to an inn in Zurich's Niederdorf and encourages him to speak out. Karl says that he fled France for fear of the death penalty: The judiciary accused him of double murder, robbery and arson, of a wealthy cattle dealer and his wife, in which he was innocent. As they come out of the restaurant, they see the headlines of the current evening paper: «Serious crime near Chartres. A Swiss is wanted. " [The typescript breaks off in the middle of the page]

Version III

Chapter 1 - «Prelude»: Wachtmeister Studer [this version plays, compared to Variations I and II, reigns after Matto , since Studer is no longer a commissioner and refers to «Matto»] has received the assignment in the insane asylum Bern to question Ernst Segesser interned there. He fled France a month ago and was arrested by Private Reinhard in Bern. Segesser is charged by the French police with double homicide, robbery and arson in Angles near Chartres. After talking to Segesser, Studer is supposed to travel to Chartres to solve the case. After the constable with Dr. Grünkern has spoken about the report of the admitted patient, he will be taken to Ernst Segesser. The two sit across from each other and Studer begins the questioning. [The typescript breaks off at the end of the page]

Emergence

The literary scholar Bernhard Echte and the Germanist Manfred Papst date versions I and II of the Angles-Roman fragment to summer 1938, i.e. shortly after Glauser settled in Nervi. Version III was probably written down in October and November.

Biographical background Angles novel

When Glauser decided to have a Studer crime thriller set in Angles near Chartres , the choice of this location had to do with his time from June 1936 to February 1937: During these nine months he lived with Berthe Bendel in the hamlet of Angles. Before this time, Glauser spent a total of eight years of his life in clinics . When he was released from the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic on May 18, 1936 , at the age of 40 he finally seemed to be given the freedom he had longed for. The plan to run a small farm in France and be able to write at the same time worked ideally. On June 1, 1936, the couple reached Chartres. From there they came to the hamlet of Angles, about 15 kilometers to the east (municipality of Le Gué-de-Longroi ). The dream of freedom and independence gave way to various adverse circumstances over the coming months. This began as soon as they arrived at the "estate" which they had leased from the Swiss banker Ernst Jucker (who worked in Paris) . The dilapidated house and the surrounding piece of land were in a desolate state; living was hard to think of. On June 18, Glauser wrote to his guardian Robert Schneider in this regard: “Dear Doctor, I would have given you notice of myself earlier, but a nasty tooth ulcer that bothered me very much only allowed me to do the most necessary gardening work. The dilapidation in which we found the Gütchen far exceeded all my expectations. There was nothing there. Mr. Jucker adored us a bed (ie a spring mattress with a mattress), nothing else. We had to buy everything else. It didn't even have garden tools. "

For the next several months, the couple tried to make a living through a combination of self-sufficiency and literary work. Glauser wrote various features articles for Swiss newspapers and magazines. A few texts were written below that describe everyday life in the hamlet of Angles, its inhabitants and its peculiarities: A chicken farm (1936), school festival (1936), July 27 (1936), village festival (1936) or neighbors (1937). In addition to working on his fourth Studer novel Der Chinese , Glauser received the notification at the end of September that Morgarten-Verlag would print Die Fieberkurve as a book if he revised the novel again. However, life in Angles increasingly became a stress test for Glauser and Bendel: Living in a dilapidated house, financial worries and the climate drained their strength. In addition, Glauser couldn't get out of being ill. Several animals that Bendel and Glauser had raised since June 1936 also died inexplicably at this time. Glauser canceled the lease and drove with Berthe Bendel to the sea in La Bernerie-en-Retz . On March 18, he wrote to Martha Ringier from there: “It is wonderful that you can work here again: You are a completely different person than in Angles. One day I would have broken myself there. [...] We have been singing and whistling again for a long time. You'll laugh at me - but I think the house in Angles was bewitched. There are such things. [...] There is someone living in the house who would like to be alone and who is sick of all inmates with illnesses. "

How Glauser wanted to weave the experiences in Angles into his planned novel remains speculation, since Studer does not reach the hamlet in any of the three Angles novel fragments . However, in addition to the announced main location, other autobiographical allusions appear. Version II says: “But a year ago he was lucky and found a job in France. Through a friend he became acquainted with a Swiss man who was a bank manager in Paris and who had bought an estate somewhere near Chartres for which he was looking for an administrator. Karl Segesser had got the job and traveled there with his wife. " And the fact that Studer goes to a restaurant with his nephew in Niederdorf probably had something to do with Glauser's former place of residence: During his time in Zurich (1916 to 1918), he lived in a room at Zähringerstrasse 40, among other things, because it was unadapted for the circumstances Lebensart he was incapacitated in 1918 by the Zurich official guardianship. ( On the 63rd anniversary of Glauser's death , the city of Zurich honored its former residents. On December 8th, the "Friedrich-Glauser-Gasse", the cross street between Niederdorfstrasse and Zähringerstrasse, was inaugurated.)

In version III, Glauser had the sergeant investigated in a psychiatric clinic at the beginning, referring to Matto governed : “Several years ago he had to treat a case that took place in a cantonal sanatorium, an institution that was popularly called madhouse. And what happened back then still stuck in my mind like an unpleasant experience ». The fact that Studer visits the Steigerhubel insane asylum in Bern in this version does not have to do with his years of internment, but finds its biographical explanation in the fact that Glauser was also admitted to the Steigerhubel insane asylum in July 1920 after an arrest in Bellinzona . From there on July 29th, with the help of his then girlfriend Elisabeth von Ruckteschell, he managed the adventurous escape in a taxi.

literature

- Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser. 2 volumes. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main / Zurich 1981, ISBN 3-518-04130-4 .

- Volume 1: A biography. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052534 ; NA: 1990, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 .

- Volume 2: A work history. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052683 .

- Bernhard Echte , Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 .

- Frank Göhre: Contemporary Glauser - A Portrait. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2077-X .

- Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 .

- Rainer Redies: About Wachtmeister Studer - Biographical Sketches. Edition Hans Erpf, Bern 1993, ISBN 3-905517-60-4 .

- Friedrich Glauser: Cracked Glass: The Narrative Work 1937–1938. Limmat Verlag , Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 .

- Hannes Binder : Sergeant Studer in Ticino. A fiction . Foreword by Peter Zeindler (= Comic Zytglogge ), Zytglogge, Bern 1996, ISBN 3-7296-0533-X .

- Heiner Spiess, Peter Edwin Erismann (Ed.): Memories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-243-X .

- Hannes Binder: A melody that the inspector had heard before ... Limmat, Zurich 2002, ISBN 3-85791-383-5 .

- Bernhard Echte (Ed.): «One can be very quiet with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 .

- Hannes Binder: Dada (Friedrich Glauser). Limmat, Zurich 2015, ISBN 978-3-85791-789-9 .

Web links

- Works by Friedrich Glauser in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Friedrich Glauser's estate in the HelveticArchives archive database of the Swiss National Library in Bern

- Friedrich Glauser's estate inventory in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 851.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 865.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 885.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 614.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 265.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , pp. 874/875.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , pp. 925–927.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , pp. 874/895.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 931/932.

- ^ Friedrich Witz: Foreword. In: Friedrich Glauser: Confession in the night and other stories. Good writings, Basel 1967, p. 5.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , pp. 267-279.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 279.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 50.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 126.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 505.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 847/848.

- ↑ Heiner Spiess, Peter Edwin Erismann (Ed.): Memories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-274-X , p. 12.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 67.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , pp. 75-78.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , pp. 76/77.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 262.

- ↑ Heiner Spiess, Peter Edwin Erismann (Ed.): Memories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-274-X , p. 14.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , pp. 75-78.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 81.

- ↑ Heiner Spiess, Peter Edwin Erismann (Ed.): Memories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-274-X , p. 13.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 83.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 89.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 30

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 90.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 263.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 1: Matto's Puppet Theater. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 30.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , pp. 273/274.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 64

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 96.

- ↑ Sergeant Studer determined. In: Cash. May 24, 1996.

- ↑ Hannes Binder: Nüüd Appartigs… - Six drawn stories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-85791-481-5 , p. 107

- ↑ Hannes Binder: Nüüd Appartigs… - Six drawn stories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-85791-481-5 , pp. 112/113

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 288.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 200.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 400.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , pp. 874/875.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 199.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 199.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 201.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (ed.): «One can be very silent with you» - letters to Elisabeth von Ruckteschell and the Asconeser friends 1919–1932. Nimbus, Wädenswil 2008, ISBN 978-3-907142-32-5 , p. 143.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 378.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 226

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 106.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 200.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 315.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 192.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 164.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 168.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 3: King Sugar. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-205-7 , p. 192.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 4: Broken glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 9.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 572.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 294.

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 4: Cracked Glass. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 300.