The three old ladies' tea

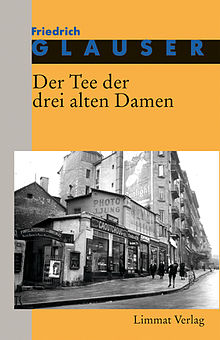

The Tea of the Three Old Ladies is the first crime novel by the Swiss author Friedrich Glauser and was written between 1931 and 1934. It is set in Geneva , where the author also spent part of his youth. The work can be described as the “problem child” among Glauser's novels, since it failed without exception in literary criticism (Glauser himself referred to it as a trash novel) and in some cases earned him the accusation of anti-Semitism .

Beginning of the novel

At two in the morning the Place du Molard is empty. An arc lamp illuminates the tram house and some trees, the leaves of which shimmer with varnish. There is also a policeman who has to guard this loneliness and is bored, because he longs for a glass of wine, because he is a Vaudois and for him wine is the epitome of home. This policeman is called Malan, he wears a copper-red mustache and yawns from time to time. Suddenly a young person stands in front of the tram booth - and it is a mystery where he suddenly appeared from.

content

Starting position

On a summer night in June, a Geneva police officer discovered a confused man on the Place du Molard who, delirious, began to take off his clothes and then fell to the floor unconscious. Shortly afterwards, the city-famous Professor Dominicé appears and informs the hospital, while the policeman examines the nearby toilet; in the process he is duped by a fleeing stranger. It turns out that the unconscious man's name is Walter Crawley and that he is private secretary to Sir Eric Bose, a diplomat from a peripheral Indian state. Crawley carried a folder with valuable documents, which, however, cannot be found. Despite the efforts of the two doctors Jean Thévenoz and Wladimir Rosenstock, the secretary dies the following day as a result of poisoning.

detection

The public prosecutor's office does not want to cause a stir and has the British secret agent Cyrill Simpson O'Key flown to Geneva so that he, disguised as a reporter, supports Commissioner Pillevuit in solving the case. A short time later, a second poisoning according to the same pattern occurs: this time the victim is the pharmacist Eltester. It turns out that the back room of the pharmacy recently served as the setting for an occult mass . In addition, Professor Dominicé was seen by witnesses at the scene again shortly before the crime. Further investigation reveals that Dominicé hired the seedy housekeeper Jane Pochon; Lately she has taken two men who have been with her lodger to the Bel-Air Psychiatric Clinic because they have lost their minds. The second patient, Nydecker, seems to know more than he is able to reveal and also dies under mysterious circumstances during the investigation into the Crawley-Eltester murder case. When the police summoned Jane Pochon for questioning, swarms of insects suddenly appeared in the Palace of Justice. In the meantime, O'Key has contacted the Russian agent Baranoff and learned that he wanted to get Sir Eric Bose's draft treaty for an Indian border state; the Maharajah of Jam Nagar had to flee there because the United States had discovered oil wells and then planned an overthrow. In order to get to the documents, Baranoff blackmailed Professor Dominicé so that he should approach Crawley and the contracts. However, the professor turns away from Baranoff and shortly afterwards gives a lecture at the university, at which he wants to confess his guilt in front of all the audience. Swarms of insects appear again and panic grips the reading room, while a poisonous arrow is shot at Dominicé, which, however, just misses its target. After investigating the incident, it turns out that the insects were not real, but the result of a consciously induced mass suggestion . To help Professor Dominicé, the brother of the assistant doctor Rosenstock, lawyer Isaak Rosène, takes care of the old man. At a meeting in the lawyer's house, the attending doctor Thévenoz unexpectedly appears and dies in front of everyone present. Secret agent O'Key then talks to State Councilor Martinet, who now takes the reins and announces the resolution of the case.

resolution

In the greenhouse of the Rosenstock family there is a fatal finale, in the course of which the mysterious master of the occult sect and also his three helpers, who helped with the crimes with their poisoned tea, are exposed. The story ends with two new lovers: secret agent O'Key and Thévenoz's former fiancée travel to the Mediterranean and Baranoff's secretary, Russian secret agent No. 83, is allowed to return to his Indian empire with the maharajah.

chaos

The literary scholar Christa Baumberger comments on Glauser's first detective novel: “ The three old ladies' tea is a real agent thriller. The spectrum of action ranges from spiritualistic séances and parapsychological phenomena to an espionage affair in Geneva diplomatic circles . There is a lot to criticize about the overloaded plot and the richly confused narrative dramaturgy. " Glauser's real strength lay not in devising a self-contained plot , but in describing moods, creating an atmosphere or portraying fates accurately and compassionately. The author Erhard Jöst writes: "With vivid milieu studies and gripping descriptions of the socio-political situation, he succeeds in casting the reader under his spell." And the literary critic Hardy Ruoss comes to the same conclusion when he states that «Glauser's crime novels cannot be reduced to the criminological framework, but rediscovered in him the social critic, the storyteller and human artist, but also the porter of the most dense atmospheres."

When it came to logically constructing a story arc the length of a novel, Glauser regularly failed. This was already evident in his first novel Gourrama and also in The Tea of the Three Old Ladies : Glauser allows too many characters (almost 30 people) to appear, sometimes overloading the complicated plot to such an extent that the tension is lost. Too many topics are broached, some seem illogical and improbable; Much remains unexplained, strange 'coincidences' lead to the clarification of open storylines and a number of clichés make the tea of the three old ladies look like a gossip novel. Glauser was probably aware of this, and he took the wind out of the sails of possible critics by having O'Key ask, towards the end of the novel Martinet: “But Mr. State Councilor, please explain to me how you like Indian petroleum sources , American missionaries As delegates of Standard Oil, secret agents of the Soviets, Basilidian gnosis , poisonous plants, witch recipes, Indian maharajas, psychologists experimenting on living material, disappeared psychiatrists, as insanely consigned harmless people, the master of the golden sky with the wooden face, stolen and reappeared portfolios and finally want to bring together tea-drinking old ladies? "

Despite all its shortcomings, the three old ladies' tea is an important novel in Glauser's oeuvre, which is why Mario Haldemann writes in the foreword of the crime thriller: “With tea he is now turning to the literary genre for the first time, from which he did not belong until his death more would be able to liberate: the detective novel. " In fact, Glauser created a preliminary stage for the future Wachtmeister Studer novels with which he should succeed in creating an investigative figure in just four years, who should establish himself in the literary genre. In keeping with this, Madge Lemoyne says in tea : “Don't make fun of detective novels! Today they are the only means of popularizing sensible ideas. "

Emergence

Preliminary study

Glauser almost certainly wrote the short story The Witch of Endor , which can be viewed as a preliminary study for the three old ladies' tea and is also set in Geneva, in the summer of 1928. In it he describes how the bank clerk Adrian Despine under the spell of his landlady Amélie Nisiow device. This influences the subtenant with their occult practices in such a way that Despine sleepwalking takes 30,000 Swiss francs from the bank, brings it back to the apartment and then has to be taken to a psychiatric clinic. When Amélie Nisiow is to be questioned about her former lodger in front of the examining magistrate, swarms of insects appear, which disrupt the trial. Glauser then reused the material of this story, including the magical additions of the witch's ointment and a coin with a god of flies, three years later in the tea of the three old ladies (especially in chapter 7.1); only the names of the people have been changed.

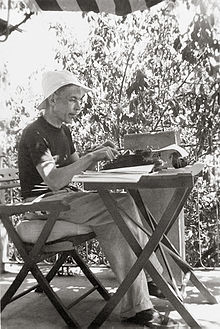

Work on the first detective novel

" The three old ladies' tea is made up as' gold tea ', if desired it is sweetened, stirred, and offered around everywhere - until Glauser lets it stand." This short sentence by the Glauser biographer Gerhard Saner describes the trials that the «tea novel» went through: From May 1931 to November 1934 Glauser worked again and again on his first great crime story. However, the writing process was regularly interrupted by his eventful life. Thus arose tea in the places Winterthur , Paris , Mannheim , in the Psychiatric Hospital Münsingen and Waldau . Although Glauser rewrote the story according to the editorial team, nobody wanted to print it. He lost interest in his unsuccessful first work and shortly afterwards began with the first Studer novel, Schlumpf Erwin Mord , with which he finally achieved his breakthrough and became a book author.

After a two-day visit to his aunt Amélie Cattin-Golaz in Geneva in May 1931, Glauser must have had the idea of writing a detective novel set in Geneva. On October 20th, he reported to his guardian Walter Schiller from Münsingen: “I'm currently working on a detective novel because I need money. It's pretty much thriving. " A letter to his then girlfriend Beatrix Gutekunst shows that Glauser started to write crime fiction for financial reasons: "Maybe I can get enough money with my novel that I can open up as a hermit somewhere in Spain, by the sea".

When Glauser was in Paris with Beatrix , he wrote to Schiller in March 1932: “I work quite a bit, and on the side I also work on a detective novel that I can certainly put together. If I can do that, I'll be out of a fix for a while. " In the same month he reported to his stepmother Luise Glauser: “I have two novels in the works [with the second novel, Glauser meant his idea about Matto ]: To make money, a detective novel that will be set in Geneva. I already have 50 pages. "

On May 21, he turned to the publisher Friedrich Witz: “I'll send you the beginning of the detective novel in the same mail and would be very grateful if you could tell me whether it might be considered for the Zürcher Illustrierte , what might happen to it would change and how much fee I could count on. [...] I'm working very hard on it and could have it ready in about a month. " Witz wrote back immediately, but was cautious: “Certainly the plot is interesting and promises to be exciting, but the work seems to be a bit overloaded with detailed descriptions and a bit poor in spice, which the readers, mainly the readers, are very reluctant to do do without, namely love. [...] On the other hand, we would like to ask you to submit the manuscript from page 64 to us after the work has been completed; only then can we come to a final decision. " In August Glauser was back in Münsingen. In a letter to Beatrix Gutekunst, he described the thriller as follows: “I think the novel will be very amusing. Such a garbage novel with backgrounds. "

In January 1933, Glauser referred to Friedrich Witz's suggestion regarding the 'spice that readers are very reluctant to do without' and reported to Schiller: “I had sent the beginning of the novel in question to Zürcher Illustrierte , and she did not seem averse to accepting it if I were to dress it up with a little more eroticism. You can do that. " At the end of September 1934 Glauser was transferred to the open colony "Anna Müller" near Münchenbuchsee (this belonged to the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic ); The three old ladies ' tea was about to end, but Glauser struggled with the dissolution. On November 9th, he wrote to Witz: "By the way, the conclusion gives me a stomachache, what you told me about bad conclusions, about unsatisfactory ones, has not fallen on sterile ground, and so I'm just grumbling at the end."

Biographical background

Locations

Geneva

The diplomatic town at the western end of Switzerland played an important role in Glauser's life, as it was here that he discovered his talent for writing, but also inspiration for the setting and characters of his novel The Tea of the Three Old Ladies . In 1913, the 17-year-old Glauser was expelled from the Glarisegg Landerziehungsheim after he attempted suicide and slapped the teacher Charly Clerc in the face. He then completed six months of land service with a farmer near Geneva and then entered the Collège Calvin (until 1969 "Collège de Genève") in September . In the first year he lived with his (step) aunt Amélie Cattin (the sister of father Glauser's third wife Louisa) and her husband Léon Cattin on Route de Chêne 23.

In 1915 the young high school student by the name of Frédéric Glosère or published pseudonym Pointe-Sèche (German: Radiernadel ) his first texts (in French) in L'Independence HELVETIQUE ; Glauser's friend Georges Haldenwang edited the feature section . By 1916 Glauser had written nine reviews and essays in a predominantly provocative style. In 1937, in the story Writing…, he remembered the time when he first published: «Last week an article appeared in the Journal Hélvetique, signed: Pointe-sèche. How nice it was to proofread, what a miracle it was to suddenly see in print the sentences that I had laboriously written in an algebra lesson. What, is it possible that the printed sentences look so different than they are handwritten? That the printing ink gives them spirit ...? "

In 1916 there was a scandal, as a result of which Glauser threatened to be expelled from school. The reason for this was his devastating criticism of Un poète philosophe - M. Frank Grandjean (1916) on the collection of poems by the college teacher Frank Grandjean. Pointe-Sèche - alias Glauser - reviewed the book over several pages in an arrogant and devastating tone and did not neglect any personal attacks. Not enough of this, shortly afterwards he duplicated Indices et restes: Actualités (1916) in his next review, among other things with the following words: «With a few pages, with a few lines, he would have made our grammar school teachers understand that silence is the greatest good is for those who have nothing to say. With his gnarled prose he would have given a proper rebuff to Mr. Chantre's derailments and Mr. Grandjean's epic bad taste. [...] You dramatic high school teachers and ventriloquists of poetry, you boys, you tiny insects - a few more escapades and you will sink into the dust that awaits you. "

Because of the possible exclusion from school, Glauser left the “Collège Calvin” and moved to Zurich to take the Matura at the “Minerva Institute”. He came into contact with the Dadaist movement . At the same time he and Georges Haldenwang founded the literary magazine Le Gong - Revue d'art mensuelle from Zurich , of which only three issues were published. In the first issue, he again scanned the works of high school writers under the title Genfer Dichter (1916): “Our magazine is concerned with sincere art. In no way a commercial purpose. To separate the true from the false. Bad smells annoy me, regardless of whether they come from the bar or the salon. And then this literary boil of the foul-smelling bourgeoisie . She has to be stabbed. [...] It is her literary works that outrage me. I'm upset because of her alone. Incidentally, it is left to the reader to check my judgment. This pseudo-poetic writing seems to me to have been fished out of the murk or to have been fraudulently stolen from the great poets of France. " This is followed by a review of seven Geneva authors, including former high school teachers.

In July 1917 Glauser traveled to Geneva for the second time and worked briefly as a milk carrier in a yoghurt factory. Back in Zurich he led an artist's life instead of studying chemistry, got into debt and finally dropped out. The consequences of this were that he was incapacitated in 1918 . He fled to Geneva, was arrested after several thefts in June and, as a morphine addict, was admitted to the Bel-Air Psychiatric Clinic for two months. This was followed by the first admission to the Münsingen psychiatric center , where Glauser was to spend a total of almost six years of his life. He was in Geneva for the last time in 1931 when he paid a two-day visit to Aunt Amélie and most likely came up with a plan to write a Geneva crime thriller. Glauser had already processed this city literarily twice: in the Geneva short story Der Heide (1917/1920) and in The Witch of Endor (1928).

"Bel-Air" clinic

After his arrest in June 1918, Glauser was taken to the “Bel-Air” psychiatric clinic. The diagnosis of the assistant doctor there, Dr. Ladame read: Dementia praecox , being mad as a youth, and was to haunt the writer all his life, as she put the stamp of “madness” on him. In the following years Glauser had contact with asylums a number of times and also processed his experiences literarily; Most aptly he succeeded in this with Matto ruled (1936), who, with his detailed interior view of a psychiatric institution, was finally declared to be Glauser's key novel.

When The Three Old Ladies' Tea was created, Glauser was already very familiar with these institutions and was able to integrate the “Bel-Air” clinic as the setting for several scenes in the novel. «Report from the night attendant: The patient was prescribed 2g of chloral at nine o'clock . Then slept quietly until half past one. [...] As the excitement returns, he receives Mo. Scop. 1 cc subcutaneously. [...] In the morning he is excited again, comes into the permanent bath ». When Glauser wrote about sleep cures, drugs such as Moscop and scopolamine solution, the Jungian association experiment in tea , he knew this from his own experience. And since he already had a psychoanalysis behind him, he could also boast with psychological expertise.

Collioure

Glauser introduces the Irish secret agent O'Key with the following words: “A young-looking man, red-haired, 1 meter 89 tall, Cyril Simpson O'Key by name, had to interrupt his vacation, which he was in Collioure , a small fishing village on the Mediterranean , close to the Franco-Spanish border. " With this short passage, Glauser paid a small tribute to the town in the south of France: In the summer of 1930 he spent two weeks there with Beatrix Gutekunst and was so enthusiastic that he went there again the next year alone. At the end of 1937, the town of Collioure entered his life for the last time, this time in a dramatic way, when on the way there the original typescript of the competition novel The Chinese on the Train was stolen and was nowhere to be found . Glauser once again brought Collioure into contact with agents when, on January 1, 1938, he wrote to his patron Martha Ringier with gallows humor from there: «Probably some soldiers said they found espionage material in the folder because they saw us reading it . There are always stupid people in this world. "

characters

Vladimir Rosenbaum

With the figure of the lawyer thought Isaac Rosenstock Glauser Wladimir Rosenbaum , his classmate from the Landerziehungsheim Glarisegg . Rosenbaum later actually became a lawyer and stayed in touch with Glauser. In his function as a lawyer, he had repeatedly helped his former classmate; financially as well as legally in trying to break free from guardianship. In the documentary Friedrich Glauser - an investigation from 1975, Rosenbaum remembered the Glarisegger time: “We were classmates. [...] Fredy Glauser was my friend in class. [...] Glauser was not a happy boy, but someone who wanted and wanted to be happy. There had been something 'scuffed' about him, something beaten up about him. What particularly impressed me, even as a boy, was his laugh. He laughed like a child who had had an accident. [...] For me it was always a tearful laugh. "

Tristan Tzara

Wladimir Rosenstock with the tireless urge to assert himself in the tea of the three old ladies is probably modeled on the Romanian Jew Tristan Tzara , who was actually called Samuel Rosenstock. Glauser got to know the writer and artist during his Dada days in Zurich and describes in his autobiographical story Dada (1931), among other things, his acquaintance and experiences with Tzara.

Théodore Flournoy

Professor Dominiceé may be a tribute to Théodore Flournoy from the University of Geneva . In the novella Demons on Lake Constance (1932) Glauser mentions Flournoy and his book From India to the Planet Mars from 1900.

Beatrix Gutekunst

Dr. Madge Lemoyne wears the characteristics of Glauser's girlfriend at the time, Beatrix Gutekunst. When he started working as an auxiliary gardener at R. Wackernagel in Riehen on April 1, 1928 , he lived with her at Güterstrasse 219 in Basel . In September 1928 he moved to the E. Müller commercial nursery in Basel, where he worked until December 1928. The two also owned an Airedale dog called "Nono", which appears several times in tea under the name "Ronny" and is described in great detail. In the detective novel Die Fieberkurve (1935) Glauser lets Gutekunst appear again , but there he draws her much more precisely and less charmingly.

Friedrich Glauser

Jakob Rosenstock bears traits of the young Glauser and his life situation at the time in Geneva: The college pupil regularly skips school, no longer has a mother and has his first experiences of being in love.

adventures

Addiction

Glauser's life was a vicious circle of addiction to morphine , lack of money, and crime against acquisitions and ended up in hospitals again and again; until the next discharge, until the next suicide attempt , until the next attempt to escape. In his autobiographical story Morphine (1932) he tells how he became an addict in Geneva: “The pharmacist from whom I got ether, a little hunchbacked man, gave me morphine at my request, without a prescription. [...] And so the accident began. [...] Food was secondary, what I earned, the pharmacist got. "

In the tea of the three old ladies , Glauser refers to this decisive experience by transferring the pharmacist from his own past to Rue de Carouge (in addition to the morphine-addicted figure of the professor) and describing it as follows: “On the ground floor of one of these tenements is a primitive pharmacy run by Mr. Eltester, an old hunchbacked man. [...] He is good-natured and likes to help where the law actually forbids help. " It can certainly be seen as Glauser's late literary revenge when Inspector Pillevuit laughs next to the corpse of the pharmacist and explains: “Excuse me, but I can't help it. When I think of this old rag Eltester - God have mercy on his soul, for he has ruined many people - when I think of this old rag as high priest, it makes me smile tremendously. "

Glauser and anti-Semitism

It is an inglorious fact that, although seldom, racist descriptions appear in Glauser's texts (mainly in the early narratives) . For example, in the tea of the three old ladies about Madame Benoît it says: “This elderly lady [...] was so shapelessly ugly that it looked beautiful again, like a pure-bred bulldog . Negro lips , cropped gray hair that was always matted. " Glauser also made use of clichés and stereotypes about Jews that were common at the time, even if this represented a clear minority in his overall work. The Geneva crime novel in particular has the property of anti-Semitism . When his literary agent Ella Picard wanted to accommodate the crime thriller in England in 1937, the publishers there regarded it as anti-Jewish and rejected it.

In 1997 Julian Schütt took up the subject again and wrote in the Tages-Anzeiger : “In the meantime, the past of some of these literary instances has been examined; literary anti-Semitism, on the other hand, is still an unreported number. It is taboo, so not a secret, but also not an issue. At most, relevant historical specialist studies and discussions sometimes do not spare us names and facts. Well-sounding names have been circulating recently: Gotthelf , Keller , CA Loosli , Glauser, Cécile Ines Loos , Inglin , Frisch , Dürrenmatt , Meienberg . A worrying continuity or mere name dropping ? Our first reaction is usually: sensitivity. Attempts to explain are quick to hand. In Glauser's case, for example, the unfortunate influence of his father and other right-wing authority figures or the corporative mentality in the Foreign Legion that is digestible for racist thinking. Finally, the zeitgeist can always be tried. [...] English agencies, really no loathers in tea and crime, reject Glauser's first crime novel The Tea of the Three Old Ladies , not least because of the penetrating taunts and resentments in the text. The perpetrator is a Jew, and his motive confirms the anti-Jewish principle cliché: greed. " In 2008 Patrick Bühler wrote the essay Alarm in Zion. Anti-Semitic stereotypes in Friedrich Glauser's detective novels , in which he mainly the tea of the three old ladies. investigated and criticized the division into “good” and “bad” Jews, stereotypes and clichéd appearances in the Jewish figures of Vladimir Rosenstock and the agent Baranoff.

Anti-Semitic sentences appear in the tea as follows (Thévenoz to Wladimir Rosenstock): «Talk to us, Rosenstock! Forget your parentage! " And three pages later: «You gossip! You can tell that you are descended from Talmudists . " And when describing the villain Baranoff, Glauser writes: "This was a man with bulging lips, the pores of the skin on his face were remarkably large, and that made the skin look somehow unclean."

Further anti-Semitic examples can be found in the short story Der Käfer (1917): “He nasalized like a Jewish lecturer, looking for old nonsense with disgustingly plump arms in his pockets.”, In the biblical-critical story Der Heide (1917/1920): “‹ Die People's stupidity, 'said Mr Benoît,' is unfathomable and for us the only measure of infinity. We are supposed to kill life because a stubborn Jew once had the idea of writing down his fairy tales. ›» Or later in the novel Die Fieberkurve , in the description of Mr Rosenzweig, «... who, despite his name, didn't look Jewish at all." And further: "The Jew who delivers the flock of sheep bribed me with three bottles."

Glauser was demonstrably not an anti-Semite, but wrote in part without reflection in the style of the zeitgeist of the Weimar Republic , in which an anti-Semitic attitude was very widespread. In contrast, his texts also contain passages against anti-Semitism and the related National Socialism : In Matto governiert Glauser criticized Hitler in a radio speech , which led to the censorship of the novel. And when it came to the filming of Wachtmeister Studer , Glauser distanced himself from the production company Frobenius, which had just become known at the time that it demanded proof of Aryan from its actors out of consideration for German financiers .

At the tea of the three old ladies it should not be ignored that the two brothers of Vladimir, Isaak and Jakob, are described positively and that Glauser uses a whole page in chapter five to weave in a humorous rabbi anecdote. This episode, in which a German officer is instructed by a rabbi, has been censored in all editions ; it was not until 1996 that the text was printed in full in the edition of Limmat Verlag .

Publications

It didn't work out with the publication of the tea and so Glauser hoped for Friedrich Witz. On May 27, 1935 he wrote to him: “Today I sent you the Geneva detective novel, and I regret that I do not have the talent of an advertising man or a hair oil manufacturer. Otherwise I would praise the novel to you in the most wonderful slogans - unfortunately I cannot. I think he's good in his way, and I've received all sorts of confirmation, including from people who weren't so sympathetic to me. " In November he received a rejection from Witz: “ I'm sending you the novel The Tea of the Three Old Ladies back here. As I said to you: I think it's good in terms of motivation, but I believe that it is only too suitable only for an intellectually high, that is, educated readership, and that the great number of our readers would look like the donkey on the mountain. "

At the beginning of December Glauser finally turned to Ella Picard, owner of the literary agency “Epic” in Zurich: “I would love to publish the novel. But it is impossible in Switzerland. I've tried every place, from the national newspaper to the Swiss media press - Mais il n'y a rien à faire. Maybe you can think of something how to use it. " On December 20, Glauser confessed to the journalist and later friend Josef Halperin: “I already get fed up with this novel, I had put a lot of hope in it to make money through it, now I would actually be satisfied if I found it somewhere could apply, even if financially not much looks out of it. " All attempts ended with rejections; among them were the Zürcher Illustrierte. the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , the Swiss Journal , the Observer , the Brofig-Verlag in Biel , Duttweiler's newspaper and also publishers in Austria and England. In 1936 the three old ladies' tea moved out of Glauser's field of vision because it unexpectedly achieved a resounding success with the Wachtmeister Studer novels.

Two years later, however, Glauser remembered his unsuccessful debut and wrote to Ella Picard on March 22, 1938: “Can I have the first crime novel that I have committed and that nobody wanted to publish again? I think it was called: The three old ladies' tea . Since nobody wants it like that, I'll redesign it as a student novel (redesign is a nice word). You have two manuscripts, one is said to still be in England and was viewed as anti-Semitic - and the other? Where is that? Please send it to me soon. "

There was no further redesign. In June he moved to Nervi near Genoa with his partner Berthe Bendel . During this half year he worked on various projects and wrote several pages a day. There was great restlessness and indecision in Glauser, so that he began to write various texts over and over again. He also had a great Swiss novel in mind. From autumn the problems in Nervi increased: The planned marriage to Berthe Bendel was delayed due to missing documents and became an endurance test; there was a lack of writing orders and the money worries grew bigger and bigger. On the eve of the planned wedding, Glauser collapsed unexpectedly and died at the age of 42 in the first hours of December 8, 1938.

After Glauser's death, the scorned 'tea novel' suddenly became attractive again for publishers. Friedrich Witz now seemed to have a different opinion than in 1935. From June 16 to October 6, 1939, The Tea of the Three Old Ladies was published as the first edition in the Zürcher Illustrierte . The thriller was suddenly introduced as "a completely new type of work, unusually worth reading in its events, which is on a par with the Wachtmeister-Studer novels." In 1941 the Morgarten-Verlag finally published the book edition, which stated on the blurb: “In no other of his novels does the poet exude his creative communicability richer and more abundantly. In his book he is truly wasteful with the booty of his observations and the results of his experiences. Just the large number of characters who appear, each of which has its own character, this colorful, multi-layered gallery of doctors, nurses, high and low police officers, spies and secret allies, this mysterious scholar, Professor Dominicé, his beautiful and clever one Assistant Mabel [in the novel there is neither a character with this name, nor does the professor have an assistant!] And the 'old ladies', this whole variety of exciting impressions compels the reader to exclaim: What kind of strange, moving thing is that again , tense book! "

reception

The three old ladies' tea was not well received by the public and panned by literary criticism. In 1970 Georg Hensel wrote a review of the Glauser edition of the Arche Verlag and said over tea , "Glauser had squandered his real experiences with drugs on unreal phantasies of agents, had assembled a stenciled backdrop from set pieces from the gossip literature." And further: "This linguistically powerful writer can only have made a mess like the tea of the three old ladies because he dared to venture into a sophisticated milieu in Geneva."

The author Erhard Jöst criticized: “But this confusion, this immense accumulation of exotic processes, that couldn't go well! Glauser's strengths seldom flash, then enrich the novel with excellent moods. But these passages are drowned in the confusion of different storylines, the assembly of which seems artificial. [...] Glauser often lets his protagonists make such complicated descriptions of complicated entanglements, and the reader will react to these passages just like the pupil: he yawns. The novel remains unrealistic and stuck in clichés. Coincidences [...] are not uncommon and contribute to the fact that this novel has to be described as a failure. "

And Mario Haldemann sees the tea novel benevolently as an agent novel parody, which does not want to be taken seriously, but writes in the afterword: “The point of view changes constantly, the 'omniscient' narrator goes through the plot now with this person, now with that person , and the reader quickly loses track of the tangled storylines and the abundance of staff. [...] There are so many of the ingredients from which this 'tea' is mixed, which with their own strong aroma do not want to match the others, that the whole brew loses all harmony in aroma and taste and is slightly penetrative smells like program: psychoanalysis, drugs, occultism, insane asylum, dark machinations. But they are only a backdrop for excitement and success and otherwise have no value. [...] The 'Swiss Simenon' , the 'Swiss Dostoyevsky' is here, after Gourrama , temporarily on strike. "

Theater adaptation

In 2012, the playwright Philipp Engelmann adapted the tea of the three old ladies for the "Theater überLand" from Langenthal . The ensemble toured Switzerland under the direction of Reto Lang. After the performance in Glarus, Südostschweiz wrote : “A morphine addict, delinquent and marginalized writer tries to earn the bitterly necessary change to live on with his detective novel“ The Tea of the Three Old Ladies ”. The book, described by the author Friedrich Glauser as 'trash literature with a background', is difficult to get hold of; it would appear in the Zürcher Illustrierte one year after his untimely death, and in 1941, another two years later, it would find a publisher. Playwright Philipp Engelmann incorporated these real circumstances into his stage version of Glauser's crime thriller by repeatedly interrupting the actual plot with fictitious telephone dialogues between Glauser and the editorial team of the “Zürcher Illustrierte”. The audience in the auditorium listens out loud as the editor mercilessly attacks the play's weaknesses: Too complex for a crime thriller, too many protagonists, too absurd topics, too little erotic ... A nifty trick that gives the play a good frame and itself the actual weaknesses of the book (later Glauser with his Studer thrillers went too big): Because just as it was a risk back then to publish the atmospherically dense and at the same time insanely confused work, it could be one today to bring it to the stage. [...] There is a lot of applause for the atmospheric staging of this bizarre society and genre study. "

Audio productions

- The three old ladies' tea. Radio play . Director: Martin Bopp , based on a radio adaptation by Albert Werner from 1964. Christoph Merian Verlag, Basel 2007.

literature

- Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser. Two volumes, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main / Zurich 1981.

- Volume 1: A biography. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052534 . (Reprint: 1990, ISBN 3-518-40277-3 )

- Volume 2: A work history. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, OCLC 312052683 .

- Bernhard Echte , Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 .

- Frank Göhre: Contemporary Glauser - A Portrait. Arche, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2077-X .

- Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 .

- Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 .

- Heiner Spiess, Peter Edwin Erismann (Ed.): Memories. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-243-X .

Web links

- The tea of the three old ladies in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Patrick Bühler: Alarm in Zion - Anti-Semitic stereotypes in Friedrich Glauser's detective novels

- Friedrich Glauser's estate in the HelveticArchives archive database of the Swiss National Library in Bern

- Friedrich Glauser's estate inventory in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christa Baumberger: Friedrich Glauser. In: Quarto. Journal of the Swiss Literary Archives (SLA) / Federal Office of Culture, No. 32, Geneva 2011, ISSN 1023-6341 , ISBN 978-2-05-102169-2 , p. 49.

- ↑ Erhard Jöst: Souls are fragile - Friedrich Glauser's crime novels illuminate the dark side of Switzerland. In: Die Horen - magazine for literature, art and criticism. Wirtschaftsverlag, Bremerhaven 1987, p. 75.

- ↑ Hardy Ruoss: Do not scoff at detective novels - reasons and backgrounds of Friedrich Glauser's stories. In: Die Horen - magazine for literature, art and criticism. Wirtschaftsverlag, Bremerhaven 1987, p. 61.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 200.

- ^ Mario Haldemann: Afterword. In: Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 263.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 127.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 198.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 101.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 355.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 412.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 383.

- ^ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 389.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 396.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, pp. 101/102.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 410.

- ^ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 419.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte, Manfred Papst (ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 1. Arche Verlag, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7160-2075-3 , p. 505.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 4: Broken glass. Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-85791-206-5 , p. 80.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 415.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 425.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 427.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 30.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 198.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 39/49.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 31.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 157.

- ^ Documentary about Friedrich Glauser - An investigation by Felice Antonio Vitali, 1975.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 67.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 2: The old magician. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , p. 127.

- ↑ From India to the planet Mars

- ^ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work. Volume 2: The Old Wizard. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-204-9 , pp. 177/178.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 44.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 51.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 75.

- ^ Julian Schütt: Anti-Semitism - Helvetian decent. Disclosure without decency: There were also anti-Jewish tendencies in Swiss literature. In: Tages Anzeiger. May 9, 1997.

- ↑ Patrick Bühler: Alarm in Zion - Anti-Semitic Stereotypes in Friedrich Glauser's detective novels. Neophilologus 2008, pp. 301-319.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 10.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 13.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , p. 27.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 25.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The narrative work, Volume 1: Mattos Puppentheater. Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-85791-203-0 , p. 57.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The fever curve. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-85791-240-5 , p. 67.

- ↑ Friedrich Glauser: The fever curve. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-85791-240-5 , p. 178.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 17.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 69.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 79.

- ↑ Bernhard Echte (Ed.): Friedrich Glauser - Briefe 2. Arche, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7160-2076-1 , p. 104.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 105.

- ^ Gerhard Saner: Friedrich Glauser - A work history. Suhrkamp Verlag, Zurich 1981, p. 106.

- ↑ Georg Hensel: Murder - bread of the poor. To two Swiss crime novels. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , July 31 / April 1. August 1971.

- ↑ Erhard Jöst: Souls are fragile - Friedrich Glauser's crime novels illuminate the dark side of Switzerland. In: Die Horen - magazine for literature, art and criticism. Wirtschaftsverlag, Bremerhaven 1987, p. 76/77.

- ^ Mario Haldemann: Afterword. In: Friedrich Glauser: The tea of the three old ladies. Limmat Verlag, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-85791-245-6 , pp. 266-268.

- ↑ «Theater überLand»

- ↑ Insane crime thriller. In: Southeastern Switzerland. February 10, 2013.