In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case |

| Genus: | Scenic report |

| Original language: | German |

| Author: | Heinar Kipphardt |

| Publishing year: | March 28, 1964 |

| Premiere: | January 23, 1964 |

| Place of premiere: | Hessian radio |

| people | |

|

|

" In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer " is a play by Heinar Kipphardt that critically examines the investigations against American scientists in the McCarthy era . The premiere as a television production took place in 1964 .

background

The drama is based on two different backgrounds. On the one hand, the American efforts to build the atomic bomb in World War II , the so-called Manhattan Project , are described, which have been started in Berkeley since 1942 by a group of physicists under the direction of the historical person J. Robert Oppenheimer . On the basis of the experience gained in this project and because of the question of loyalty to Oppenheimer's refusal to participate in the construction of the hydrogen bomb in 1951 , the US Atomic Energy Commission set up a committee of inquiry whose task it was to examine the loyalty of the scientists.

Oppenheimer, a native American of German descent, was subjected to violent interrogations for three weeks in 1954 because he was accused of sympathy with communism and treason. In 1954, proceedings were initiated against Oppenheimer. It ended with Oppenheimer being deprived of the necessary security guarantee for further work on government projects. It was only in 1963 that President John F. Kennedy rehabilitated the scientist.

action

1st chapter

1st scene

On April 12, 1954, the Committee of Inquiry of the Atomic Energy Commission met for the first time. This should clarify whether the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer can be given the security guarantee. The committee is composed of Chairman Gordon Gray, a newspaper publisher, radio station owner and former Secretary of State in the Department of War, Ward V. Evans, a professor of chemistry in Chicago, and Thomas A. Morgan, general manager of the Sperry Gyroscope Company , a nuclear equipment company. together. Roger Robb and CA Rolander, a Robb employee and safety specialist, represent the Atomic Energy Commission. Oppenheimer is represented by lawyers Lloyd K. Garrison and Herbert S. Marks.

As a witness, Oppenheimer himself is first questioned. Marks plays an interview with Senator McCarthy in which McCarthy sees the development of the hydrogen bomb and the US nuclear monopoly as threatened by communism and communist traitors. When asked whether he recognizes the committee, Oppenheimer criticizes the fact that there are hardly any scientists in it. He is willing to take his testimony under oath , although it is not required.

Atomic Energy Commission attorney Roger Robb questions him about his involvement in the US nuclear weapons research project. Oppenheimer rejects the designation "father of the atomic bomb", although he was involved in the construction of the atomic bombs " Little Boy " and " Fat Man ". He explains that he was used by the War Department as a scientific advisor in selecting the locations for the atomic bombs to be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki . He should evaluate the suitability of the destinations Hiroshima , Kokura , Nigata and Kyoto . The target should be as unaffected by bombing as possible and have a high military-strategic value in order to be able to measure the effect of the atomic bomb precisely.

However, Oppenheimer rejects political responsibility for the atomic bombs, as he was only employed as an advisor to the War Ministry and did not make the decision. He expressed moral scruples about the killing of civilians, 70,000 according to him. He explains that he helped develop the atomic bomb in order to forestall Hitler Germany in it and thus prevent it from being used. However, Oppenheimer would not have advocated the use of a hydrogen bomb on Hiroshima, since the city was not suitable as a target for a hydrogen bomb because it would be too small.

Robb now questions Oppenheimer about the allegations of the Atomic Energy Commission. He replies that the allegations depress him because they do not appreciate his work for the United States and falsely accuse him of actively resisting the construction of the hydrogen bomb by influencing other scientists. Robb announces that he will deal with Oppenheimer's connections, whereupon Garrison requests that older accusations, which should already be clarified in previous proceedings, should not be the subject of the proceedings. Robb objects that he has further evidence against Oppenheimer. Gray rejects the application because of this.

1st cutscene

Evans shows interest in Robb, who then explains to him why he is convinced that the allegations against his former idol Oppenheimer are justified in his opinion. However, he cannot explain why Oppenheimer rejects the development of the hydrogen bomb. Evans speculates that he might be afraid of this one. Robb wants to make Oppenheimer's feelings and motivations the subject of the proceedings in order to achieve a complete clarification. Evans wonders, however, whether he is violating Oppenheimer's privacy and whether Robb's views are still within the rule of law .

Robb: "If the security of the free world depends on it, we have to push our discomfort to the limit."

Evans: "Sometimes maybe about that too?"

Robb: "I think Dr. Evans, there is quantitative and qualitative analysis in chemistry . ”He laughs.

2nd scene

The next day, the second day of the negotiation, Robb asked Oppenheimer about connections to the communist party and his attitudes towards communism . Oppenheimer said that although he had sympathy for communism, this disappeared during the tyranny of Stalin . During the development of the atomic bomb he had to cut ties with some communist friends because he had to develop the atomic bomb in the desert under military security conditions. Robb continues on the relationship with his then fiancée Dr. Jean Tatlock one. This was a changeable member of the communist party.

Robb: "... Was your former fiancée Dr. Jean Tatlock member of the communist party? "

Oppenheimer: “Yes. Less for political than for romantic motives. She was a very sensitive person, deeply despaired of the injustices of this world. "

Tatlock committed suicide . She met her fiancé shortly before her death and they stayed one night in a hotel. Oppenheimer asks what that has to do with his loyalty, but Robb sees the meeting as a communist gathering. Oppenheimer is outraged. He refuses to answer the question of what he was talking about with his fiancée that night and takes the stand. Garrison objects and demands that the question not count. Gray accepts the objection.

2nd cutscene

Evans expresses serious doubts to Morgan about the purpose of the interrogation . He wonders whether the principle of loyalty will result in a surveillance state that checks and evaluates the loyalty of its members, sets its own standards, and whether science is helping to develop this technology. Morgan replies that future generations of scientists have adapted to these conditions.

Evans: “... I don't know if I want to get used to transparency, if I want to still live then? "Do not speak, do not write, do not move" is the motto today at universities, if this continues, how should it continue? "

3rd scene

On the third day of the interrogation, Robb discusses Oppenheimer's links to communism during the Spanish Civil War . Oppenheimer supported the people who fought against Franco and the Nazis in Spain with $ 300 a month. He was close to the communist organizations, but was not a member of the communist party and did not want to join it, as he did not want to be influenced in his independence . He saw the world threatened by fascism and communism as an alternative that actively opposed it.

Robb: "What worried you?"

Oppenheimer: “What worried me, Mr. Robb? - That the world was watching with its hands in its pockets. I had relatives in Germany, Jews whom I could help to come to this country, and they told me what was happening there. "

Robb suspects Oppenheimer that on July 23, 1941, a closed meeting of communist functionaries took place in his house in Berkeley . A communist functionary named Schneidermann is said to have presented “the new line of the communist party” at the meeting . A witness named Paul Crouch and his wife are said to have testified. Marks requests that the witnesses appear and testify to their testimony. However, this is not possible because the FBI has not released the witnesses for the case. However, Marks can then prove that Dr. Oppenheimer and his wife were in New Mexico and not Berkeley at the time.

3rd cutscene

Oppenheimer rejects the use of a telex draft from Marks, a telex text used at the time. Marks wants to bring the negotiation to the public in order to make Oppenheimer's defensive defense more offensive. The lawyers want to make the case available to the public. However, Oppenheimer does not want the lawyers to proceed in this way, but rather that they continue to rely on his defense. Garrison and Marks see the trial as an example of suppressing science. The defense has no access to the items on the agenda.

... Garrison: “If it were a matter of facts, if it were a matter of arguments. It's about you as a political example. "Oppenheimer:" Then why not McCarthy, but this hearing? "Marks:" You are the goat that has to be skipped over to force the submission of science to the military, the intimidation of the people, who call an ox an ox, despite McCarthy. "Garrison:" If the boss of Los Alamos , if Oppie is a traitor, a communist in disguise, then nobody can be trusted, then everyone here must finally be monitored and screened. "

But Oppenheimer is not interested in that, just a guarantee of security. But since Oppenheimer's employment contract only runs for 3 months anyway, this procedure would not be necessary without a political background. Marks compares Oppenheimer's witness position with the Maid of Orléans .

4th scene

At the interrogation on the 5th day, Oppenheimer will be asked about his selection criteria for the scientists involved in the nuclear weapons project. He says that although he thought it was possible then to use a communist on the project, it is no longer possible today. He justifies this with the fact that the Soviet Union was an ally of the Western powers at the end of the Second World War . After the Second World War, however, this was no longer conceivable, as Russia turned out to be a possible opponent of America during the Cold War. The US Communist Party was used as an instrument of espionage, which Oppenheimer was not aware of as it was a legal party and had supported America in the fight against Hitler Germany. Oppenheimer did not propose any members of the Communist Party because he could not be sure that they were loyal to the United States. He saw the danger of indiscretion. However, he did not necessarily see this danger in former members of the party.

Robb now wants to know from Oppenheimer how he checked the loyalty . As an example, he gives Oppenheimer's brother, who was a member of the Communist Party. Oppenheimer, however, did not consider such a confidence test necessary for his brother, as he considered him trustworthy. He is of the opinion that while it generally makes sense not to involve communists in the projects, in exceptional cases there are also those who prove to be loyal. As an example, he cites Frédéric Joliot-Curie , a physicist who was involved in the French nuclear weapons project and was close to the French Communist Party during the occupation. Robb names scientists who spied on the atomic bomb project - Klaus Fuchs , Nunn May and Bruno Pontecorvo . Evans wants to know from Oppenheimer whether he knew Fuchs better. The latter states that he only knew him briefly and thought he was very introverted . As a justification for the disclosure of the information to the Russians, Oppenheimer cites "somewhat presumptuous ethical motives" that he does not want the bomb to be in the hands of just one power, since it could then misuse the bomb. He says that Fuchs "played a bit of the role of God, of world conscience" and explains that he rejects this attitude.

The Russians did not get any essential information for the construction of their atomic bomb from the information from May and Fuchs, because their concepts were structured differently. The questioning is now directed back to Oppenheimer's brother. He joined the party between 1936 and 1937 and left in 1941. He was first used on non-secret projects at Stanford, but later went to Berkley, where he worked on secret radiation projects. Oppenheimer did not inform the security authorities that his brother was a member of the Communist Party.

Oppenheimer: "I think I am not obliged to destroy my brother's career if I have full confidence in him." Oppenheimer stands behind his brother. When asked Robbs whether he approves of his brother's denial of membership in the Communist Party, Oppenheimer replies: “I don't approve of it, I understand it. I disapprove of a person being destroyed because of his current or past beliefs. I disapprove of that. "

Oppenheimer criticizes that people are ready to give up their freedom in order to protect them.

4th cutscene

Rolander uses his voice recorder . He draws parallels between the threat posed by the Nazis to the Western powers and the threat posed by the Soviet Union. According to him, security issues “do not claim to be absolutely just and inviolable moral. They are practical. ” He sees the nature of the private sphere as a hindrance to the investigation and wants to examine Oppenheimer's connections and sympathies and assess what effects they have had in the past and whether they pose a threat in the present.

Rolander: “I feel so old among older people. Where they have ideology is just a blind spot for me. "

5th scene

On the 7th day of interrogation, Rolander asked Oppenheimer about political sympathizers at the time of the Manhattan Project. He wants to find out the reasons why so many physicists in Los Alamos sympathize with communism. Oppenheimer: “Physicists are interested in new things. They like to experiment and their thoughts are focused on change. In their work, and so also in political questions. ” Rolander names some of the students of Oppenheimer, Weinberg, Bohm, Lomanitz and Friedman who had communist inclinations. Oppenheimer used this in the Manhattan project because he considered it to be technically competent.

When Rolander asks why Oppenheimer had so many communist relationships, he replies:

“Yes, I don't find that unnatural. There was a time when the Soviet experiment had a great attraction for all those who found the state of our world unsatisfactory, and I think it really isn't satisfactory. Today, as we view the Soviet experiment without illusions, today, when Russia faces us as a hostile world power, we condemn the hopes that many people have attached to trying to find more sensible forms of human coexistence with greater social security. That seems unwise to me, and it is inadmissible to belittle and persecute them because of this view. "

He criticizes the fact that "a person cannot be taken apart like a primer" and that one cannot judge people on their own based on the relationships they have. His two students, Weinberg and Sohm, were members of the Communist Party. After this came out, Oppenheimer recommended them a lawyer and also attended their farewell party. He states that because of the high unemployment, which also affected his students, he was close to the Marxist ideas , in which he saw an alternative, at least at times.

5th cutscene

Morgan and Gray smoke cigars. Morgan tells Gray that Oppenheimer's political attitudes are being addressed to a large extent in the process. The subjective opinion of scientists does not matter to him as long as it does not influence their objective work. It should be clarified whether Oppenheimer adhered to this. Gray agrees with him.

6th scene

The 10th day of interrogation, April 22, 1954 , is Robert Oppenheimer's 50th birthday. Robb congratulates him. He asks if Haakon Chevalier sent him a birthday card. Oppenheimer says yes. Chevalier is a French writer who represents leftist views. He is a friend of Oppenheimer's. Oppenheimer learned from Chevalier at a party in the winter of 1942/43 that the chemical engineer Eltenton had passed on information about the atomic bomb project to the Russian secret service.

Oppenheimer is negative about it "... I mean, I said:" But that's treason! " ? I'm not sure, anyway I said something of the kind that would be terrible and out of the question. And Chevalier said that he totally agreed with me. "

However, Oppenheimer did not report the incident until six months later to the security officer Johnson and later to his superior Colonel Boris Pash . To protect Chevalier, however, he did not name him when making this statement, but invented "a robber pistol". He stated that he learned of Eltenton's intentions through 3 middlemen. He didn't want to name Chevalier to protect him or to keep him out of the picture. It was only when General Groves gave him the military order to name the names that he called himself and Chevalier. Colonel Pash, summoned by Robb, incriminates Oppenheimer. He is convinced that the statement that Oppenheimer made first was the truth and that Oppenheimer poses a security risk.

Oppenheimer's statement about the Eltenton affair against Pash is recorded on a video tape from the summer of 1943. Here Oppenheimer tells the version of the events that he says was invented. After Pash is released, lawyer John Lansdale, who was in charge of security for the Los Alamos nuclear weapons project, is heard. He was responsible for giving Oppenheimer the security guarantee or for denying it to him. At the time, Oppenheimer was considered the only one who was able to realize Los Alamos. However, the FBI was skeptical of him. In order to come to a decision, Lansdale had him monitored. Lansdale was convinced that Oppenheimer was not a communist and that he wanted to protect his brother and not Chevalier. He states that Oppenheimer's behavior was typical of the scientists. Rolander asks him what he did with the recordings of the conversation between Oppenheimer and Jean Tatlock. He says that he destroyed the recordings.

When Rolander wants to find out the content of the conversation, Lansdale does not provide any information, as he thought the conversation was too private. Gray confirms that he does not need to make any statements based on the earlier motion. Lansdale sees the process as hysterical and criticizes that things that took place in the past were judged with current feelings. Dr. Evans questioned the two witnesses about safety in nuclear weapons projects. Pash believes that freedom must be restricted to maintain security. Lansdale is more skeptical. He believes that to give up freedom means giving up what you are trying to protect. At the end of the scene, Gray adjourned the meeting. He announces that Oppenheimer's behavior in relation to the hydrogen bomb will now be dealt with.

Part 2

7th scene

At the beginning of the 7th scene we learn that a letter from the Atomic Energy Commission and Oppenheimer's reply to it have been given to the New York Times . Robb and Marks blame each other for not sticking to the agreement and for taking the matter to the press. The interrogation now goes into greater detail on the question of Oppenheimer's behavior in relation to the hydrogen bomb .

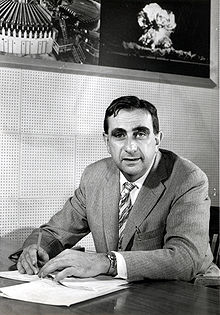

Oppenheimer sees this weapon as very problematic and would like the two great powers America and Russia to waive it, but rejects allegations that he delayed the development or countered it due to moral concerns. He behaved neutrally on this issue and at times also supported the development. The physicist Dr. Edward Teller , who also worked in Los Alamos and developed the hydrogen bomb, is interrogated. This indicates that Oppenheimer acted “waiting and neutral” when developing the hydrogen bomb, but would not have supported the development either.

Oppenheimer showed no enthusiasm. The hydrogen bomb could be developed with Oppenheimer's support before, but plate is asked the legitimate question of Evans whether "one can accuse a man that he has not enthusiastic about a certain thing, the hydrogen bomb in our case?" . He sees Oppenheimer as "subjectively" loyal, but would "feel safer if the most important interests of the country were not in his hands." He denies the question of whether he had any moral scruples; the effects of the use of the bomb could not be foreseen and he hoped that it would never be used.

The next witness will be Dr. Hans Bethe questioned . He was the head of the theoretical physics department in Los Alamos and was also involved in the development of the hydrogen bomb. He can understand Oppenheimer's doubts and explains that he himself only worked on the hydrogen bomb for pragmatic reasons.

Dr. David Griggs , the chief scientist of the Air Force , sees Oppenheimer as part of a conspiracy against the construction of the hydrogen bomb. Dr. Rabi wrote "ZORC" on a board during the Vistas project. This is said to stand for the names Zacharisas , Oppenheimer, Rabi and Charlie Lauritzen , which supposedly formed a group that strives for world disarmament. He sees Oppenheimer as a security risk.

Dr. Isidor Isaac Rabi reveals the background to "ZORC". At the conference, it was not he who wrote, but Dr. Zacharisas, a US Navy nuclear physicist , on the blackboard. It is an allusion to a "piggy" article in Fortune magazine . Zacharisas did this because Griggs responded to his opponents not with arguments but with suspicions. Rabi sees himself in a similar position as Oppenheimer. At first he found Oppenheimer's lies in the Eltenton affair “foolish”, but can now understand his behavior. He considers Oppenheimer to be absolutely loyal and sees the negotiation as a great danger to science. Gray emphasizes that this is not a real legal process, but Rabi still sees its importance higher than a normal process.

8th scene

On May 6, 1954, the legal representatives were given the opportunity to make their plea . For the Atomic Energy Commission this is what Robb holds. Oppenheimer can no longer be given the security guarantee because he had too strong connections to communists and was therefore too close to these ideologies in his ways of thinking. The fact that Oppenheimer was no longer actively involved in the development of the hydrogen bomb is what he calls "treason" in relation to his leftist views. Robb's ideology is to defend the security of his country at the expense of freedom.

The plea for Oppenheimer is made by his lawyer Marks. He pleads for Oppenheimer's loyalty to the United States, especially with the development of the atomic bomb. He also took his position on the hydrogen bomb because he was concerned about the welfare of the country; a worldwide declaration of renunciation would be better for all civilization, since it would also bring peace to his country. He considers Robb's views to be extremely dangerous as they run counter to democratic freedom. Gray adjourns the judgment meeting.

9th scene

The judgment of the commission is announced. Gray and Morgan are of the opinion that Oppenheimer can no longer be given the security guarantee. They justify their decision with the behavior of Oppenheimer in the Eltenton affair, as well as his non-participation in the hydrogen bomb development. Evans writes in his minority report that Oppenheimer is still to be given the security guarantee. He saw no doubts about his loyalty, he even believed that Oppenheimer's behavior in relation to the hydrogen bomb was correct and that it was his civic duty to express his opinion on this important issue.

The majority of the committee is against the granting, and Oppenheimer's security guarantee is withdrawn. Gray makes it clear that Oppenheimer has the opportunity to appeal against this judgment to the Atomic Energy Commission. At the end, Oppenheimer was given the opportunity to make a conclusion. In the historical case, however, he did not get this opportunity. In his closing speech, he critically questions the loyalty of physicists to the government. He ends his remarks with the words: “We have done the work of the devil and we are now returning to our real tasks. ... We can do nothing better than to keep the world open in these few places that need to be kept open. "

Text type and structure

The play is generally counted to the group of documentary theater , which was mainly used for politically oriented theater plays in the 1960s. In contrast to the classic drama, the pieces relate to historical documents and facts, which is intended to achieve a documentary effect. According to the author, an essential source of the text is the FBI protocol of Oppenheimer's interrogations, which comprises around 3,000 machine pages.

In Kipphardt's play, in contrast to the correct interrogation, 6 instead of 40 actual witnesses are heard. The statements of these should all contain the statements actually made as realistically as possible in order not to shape the drama too extensively. So he took the liberty of translating the interrogations into a literary form. He therefore built mini-scenes and monologues into the drama that did not take place in the actual trial. Nevertheless, he tried to reproduce the historical events as accurately as possible. He proceeded according to the principle of changing "as little as possible and as much as necessary" to the original protocols. He justified this way of working with Hegel's aesthetics .

Kipphardt's piece corresponds to the rough structure of a court case. It begins with the interrogation of witnesses and the accused by lawyers on both sides, followed by the pleadings and finally concluded with the pronouncement of the verdict and the accused's closing remarks.

main characters

Oppenheimer

In this piece, Oppenheimer embodies the typical physicist at the time of the action, in the conflict between loyalty to the state and to humanity. The main character in this book is also not portrayed as a kind of "hero" with positive traits, but as a neutral character.

On the one hand, he acts indulgently and sensibly towards humanity when he speaks out against the construction of the hydrogen bomb because of the consequences he was aware of. At the same time, he appears quite arrogant and cold-hearted towards the committee throughout the negotiation. He is of the opinion that his friend Chevalier would not have understood anyway if he had explained to him that he had started the espionage business against him. He also appears very superficial and arrogant in his testimony about physicists who share the government's views. This can be interpreted as an attitude to only cooperate with the committee of inquiry as much as is absolutely necessary, but actually not to recognize it and its methods.

Although Oppenheimer tries to use tactics during the entire interrogation, his statements often seem contradictory, indecisive and inconsistent, and his actions and statements often lead to the opposite result. Above all, his behavior in the Chevalier affair is incomprehensible, because of his long hesitation and his false, contradicting statements with which he tries to protect his friend, ultimately lead to the opposite result, namely that Chevalier loses everything. Oppenheimer shows a mental non-sovereignty here, which could be a result of the weeks of interrogation.

He is also unable to openly express his scruples about the consequences of the atomic bomb. Instead, he repeatedly expresses his feelings in well-known literary quotations, e.g. B. from Hamlet. With this obscure, inconsistent formulation of his position, he finally made it easy for the prosecution to demonstrate a disloyal attitude towards the government. It is speculative whether that was perhaps even his intention in order to be able to finally evade the hydrogen bomb project in this way.

Apparently Oppenheimer acts naively when he z. B. does not want to go public because he thinks he can convince the committee that way. This makes it easy to let the process stand as a political example. During the process, Oppenheimer nevertheless goes through a change. In the end he has to realize that he is guilty in a certain way, namely insofar as he realizes that he has surrendered physics to the military for far too long and is now helpless before the effects.

The committee

While the two members Morgan and Gray declare Oppenheimer to be disloyal to the government, Evans can see no disloyalty in Oppenheimer's actions. As the only scientist on the committee, he recognizes Oppenheimer's conflict situation. He tries to clarify this conflict throughout the interrogation, but is ultimately overruled by his colleagues.

The witnesses

Edward Teller emerged as a clear contrast to Oppenheimer during his interrogation. He regards the discoveries of the scientists as morally neutral, what the military would make of them is no longer a matter for the physicists, and he also regards progress as the only reasonable thing. In his case, too, it remains unclear what his actual convictions are and what he may only say to the committee in order to prove his loyalty (e.g. the “neutrality” of the scientists).

During the entire interrogation he appeared straightforward and almost belligerent; unlike Oppenheimer, he appeared determined and cautious, but also mentions that, unlike Oppenheimer, he was ready to help develop the hydrogen bomb, but agreed with Oppenheimer in the hope that it would never be used would. Also Griggs , who is described as ambitious, pretty and insignificant states against Oppenheimer. However, he does not seem particularly credible, as his conspiracy theory is based solely on questionable press reports. His personal rejection of Oppenheimer is very clear.

Bethe and Rabi, however, exonerate Oppenheimer. Bethe represents Oppenheimer's opinion on disarmament. He also cites the scruples of physicists as reasons for the delay in building the hydrogen bomb. In contrast to Bethe, who appears calm and matter-of-fact, Rabi appears impulsive and personally attacked by the allegations. He defends his friend Oppenheimer by praising his services to science.

The secret service agents Pash and Lansdale represent two opposing opinions: Pash considers Oppenheimer to be still communist and therefore a security risk, while Lansdale regards Oppenheimer as a liberal person.

Dramatic conflict

The core of the play is the conflict between the scientist who has a special social responsibility and a state that demands absolute political loyalty from its citizens (especially in the context of the early Cold War and the persecution of the McCarthy era ).

The situation for the scientists is difficult: While their results were previously intended exclusively for the whole of humanity, their entire work is now subject to their respective state, which decides on the publication or the exclusively secret, military use of the findings. So the scientists are mindless servants of the state. Many physicists, like Oppenheimer, realize far too late, however, that they have long since become immature tools for the competing states. They are subject to the state and their research, which was actually intended for the benefit of mankind, is now directed against mankind in the form of weapons.

It is precisely this fact that Oppenheimer calls the actual betrayal in the entire proceedings, in no way the betrayal by espionage of a state to which one is subject, but exclusively the previous betrayal of science. Oppenheimer says that, contrary to the indictment, he even pledged too much loyalty to the United States and betrayed the ideals of science by completely submitting to the military.

Kipphardt thus represents a similar conflict as it is also thematized in Brecht's Life of Galileo and Dürrenmatt's The Physicists .

reception

Kipphardt had made personal contact with Oppenheimer. However, Oppenheimer rejected the first piece drafts due to errors in content by Kipphardt. Kipphardt accepted Oppenheimer's criticism and deleted various passages. He wrote an article that set out the differences between the historical negotiation and the play. This article should be included in the program of each performance. Oppenheimer threatened Kipphardt to take legal action against the play, but regretted these statements in one of his last letters. Oppenheimer died shortly afterwards.

After Kipphardt's play was shown as a television documentary on January 23, 1964 by Hessischer Rundfunk (director: Gerhard Klingenberg ), Kipphardt developed a theatrical version that same year, which was shown on October 11, 1964 at the Freie Volksbühne in Berlin (director: Erwin Piscator ) and was premiered at the Münchner Kammerspiele (director: Paul Verhoeven ). Kipphardt was awarded numerous prizes for the play. The success reached far beyond the German borders. Kipphardt received the first television film award from the German Academy of Performing Arts and the critic award of the international television festival in Prague .

The French director Jean Vilar created a French version of the Oppenheimer material under the title Le Dossier Oppenheimer and staged it in December 1964 at the Théâtre National Populaire . The director pretended to have created a new play based solely on the interrogation records. Kipphardt contradicted this in an article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung . Vilar's version puts Oppenheimer in a heroic light and only partially corresponds to the minutes. Vilar's theatrical text is based on his own piece, which has only been marginally changed. After Suhrkamp Verlag had threatened Vilar legal action for violating copyright law , the director relented and identified Kipphardt's play as the basis of his stage text.

In 1977 Kipphardt worked on a new version of the play for a Hamburg production.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Description of the work at the Suhrkamp publishing house

- ↑ In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Heinar Kipphardt: In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer, A piece and his story (work edition), ISBN 3-499-12111-5 , follow-up, pages 110–111.

- ↑ Heinar Kipphardt, In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer, edition suhrkamp No. 64, ISBN 3-518-10064-5 ; P. 90, lines 13-19; 91, lines 4-14

- ↑ ibid., P. 64, lines 5–10

- ↑ ibid., P. 44, lines 19-23

- ↑ ibid., P. 16, line 12; P. 91, lines 29-36

- ↑ ibid., P. 34, lines 1–5

- ↑ ibid., P. 139, lines 3-18

- ↑ ibid., P. 106, line 13 - p. 107, line 15

- ↑ ibid., P. 116, lines 10-11

- ↑ ibid., P. 118, lines 8-10

- ↑ Heinar Kipphardt, In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer, A piece and his story (work edition), pp. 159ff., ISBN 3-499-12111-5

- ↑ Heinar Kipphardt, In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer, A piece and his story (work edition), pp. 180ff., ISBN 3-499-12111-5

literature

expenditure

- Heinar Kipphardt: In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case . Frankfurt am Main 1964 (edition suhrkamp no.64), ISBN 3-518-10064-5 .

- Heinar Kipphardt: In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case. A piece and its story . Reinbek near Hamburg 1987 (work edition). ISBN 3-499-12111-5 .

Secondary literature

- Horst Grobe: Heinar Kipphardt: In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case. Hollfeld: Bange Verlag 2005 (King's Explanations and Materials, Vol. 160). ISBN 978-3-8044-1774-8 .

- Sven Hanuschek: “I call that finding the truth”. Heinar Kipphardt's Dramas and a Concept of Documentary Theater as Historiography . Bielefeld: Aisthesis 1993, ISBN 3-925670-88-2 , pp. 105-162.

- Ferdinand van Ingen: Basics and thoughts for understanding the drama "Heinar Kipphardt, In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer" . Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Munich: Diesterweg 1990 (= 1978). ISBN 3-425-06078-3 .

- Heiner Teroerde: Political dramaturgies in divided Berlin. Social imaginations with Erwin Piscator and Heiner Müller around 1960 . Göttingen: V&R unipress 2009. pp. 222–250.

- Theodor Pelster: reading key. Heinar Kipphardt: In the J. Robert Oppenheimer case. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008. ISBN 978-3-15-015388-8 .

Web links

- On the merits, J. Robert Oppenheimer in the Internet Movie Database (English)