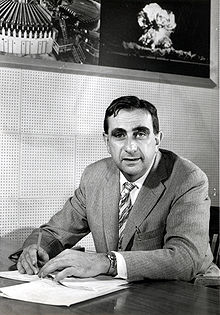

Edward Teller

Edward Teller , German Eduard Teller , Hungarian Ede Teller (born January 15, 1908 in Budapest , Austria-Hungary , † September 9, 2003 in Stanford , California ) was a Hungarian - American physicist . He made important contributions in various areas of physics. He became known to the general public as the "father of the hydrogen bomb ". Teller himself rejected this title for himself.

Teller studied at the Technical University of Karlsruhe and received his doctorate in Leipzig in 1930 under Friedrich Hund and Werner Heisenberg . Because of his Jewish origins, he decided in 1933 to leave National Socialist Germany and emigrate to England. In 1935 he emigrated to the USA. There he became an employee of the Manhattan project , which developed the first atomic bombs, very early on . During this time he was already pushing for the additional development of fusion-based nuclear weapons. Many of the physicists who had worked with him in the Manhattan Project later opposed the further development of nuclear weapons technology and the subsequent nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union , while Teller vehemently advocated it because of the " threat from communism ".

In interrogation about the security classification after the end of the war, Edward Teller incriminated Robert Oppenheimer , his former colleague at Los Alamos National Laboratory , causing him to lose reputation in the scientific community. However, he continued to receive support from the US government and military researchers. Teller was one of the co-founders of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory for Nuclear Weapons Research Center and for several years was its director, later deputy director.

In later years Teller became known mainly for controversial technical approaches to military as well as civilian tasks, for example a plan to build an artificial harbor ( Operation Chariot ) in Alaska by detonating hydrogen bombs. He was a prominent supporter of Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) and was later accused of covering up the very difficult feasibility of the program.

Teller was known throughout his life for both his great scientific prowess and problematic interpersonal behavior. He is considered one of several role models for the figure of Dr. Strangelove (German "Dr. Strange") in Stanley Kubrick's film satire Dr. Strange or: How I Learned to Love the 1964 Bomb .

Origin, education and early years

Childhood and youth

Teller was born in 1908 in Budapest in what was then Austria-Hungary as the second child of the lawyer Max Teller and his wife, the pianist Ilona Deutsch Teller. Teller's sister Emma is the mother of the physicist Janos Kirz . The plates were wealthy, assimilated Jews whose fortunes were decimated under the brief communist rule of Béla Kun during the Hungarian Soviet Republic after World War I. As a child, Teller learned to speak late, which is why his grandfather thought he was retarded. Teller later explained this with the fact that his parents had different mother tongues. His father spoke Hungarian and only a little German, while his mother spoke German as her mother tongue and had a poor command of Hungarian. As a child, he had to think in two languages all the time. Edward and his sister Emmi initially received private lessons from an English teacher. He then attended the ELTE Trefort Ágoston Gyakorlóiskola , a renowned grammar school in Budapest. As the most impressive events of his childhood, Teller later described the outbreak of World War I and the death of Emperor Franz Joseph I with the subsequent coronation ceremonies of the new heir to the throne Charles IV as King of Hungary in 1916. Although he was interested in mathematics at a young age interested and for example, the algebra of Euler read, he temporarily lost interest in mathematics because of unpleasant experiences with his math teacher.

Chemistry degree

After graduating from school in June 1925, Teller wanted to study mathematics, but encountered opposition from his father, who thought this was a “jobless” subject and persuaded his son to start studying chemical engineering instead . According to his mother's ideas, however, he should have pursued a career as a pianist. Teller studied in Budapest for the first semester. He took part in a physical-mathematical competition at the university, in which he won the first prize named after the Hungarian physicist Loránd Eötvös . At the beginning of 1926, Teller moved to the Technical University of Karlsruhe , which at the time had an excellent reputation in chemistry. In addition to lectures in chemistry, Teller also attended lectures in mathematics and physics. In doing so, he developed a keen interest in the emerging quantum mechanics .

Change to quantum physics

After two years of studying chemistry, Teller finally asked his father for permission to change courses. The father then traveled to Karlsruhe, spoke to the professors, and the son finally received his father's consent to switch to physics. Later, Teller particularly emphasized the influence of Hermann Mark , who was then a lecturer at the university. In 1928 he moved to the University of Munich to study with Sommerfeld . However, he was not very impressed by Sommerfeld. In Munich, when he got off the step of a moving tram , Teller got his foot under the wheels, so that his foot had to be amputated. Teller remained on friendly terms with the operating surgeon Paul von Lossow , a brother of General Otto von Lossow , who had helped to thwart the Hitler coup of 1923. All his life he had to wear a prosthetic foot and dragged the affected leg.

Doctorate with Hund and Heisenberg and assistantship

In 1928 he switched to Friedrich Hund and Werner Heisenberg at the University of Leipzig and received his doctorate there in 1930 . The subject of his dissertation , the quantum mechanical description of the ionized hydrogen - molecule was excited by Heisenberg. The doctoral thesis was supervised by Friedrich Hund and published under the title About the Hydrogen Molecule Ion in the Zeitschrift für Physik . In the doctoral examination, Teller received the grade “I excellent” from all three examiners, Hund (physics), Paul Koebe (mathematics) and Max Le Blanc (chemistry). From 1931 he worked at the University of Göttingen with James Franck , Hertha Sponer and Arnold Eucken .

Emigration from Germany and marriage

The appointment of Hitler as Reich Chancellor in January 1933 and the subsequent mass dismissal of Jewish academics as well as the persecution of the Jews recommended that Teller should not remain in Germany, even though, as a Hungarian citizen, he was not directly affected by the repression that followed. So in 1933 he left Germany for England and worked briefly for Frederick George Donnan , where many scientists who had fled Germany had gathered. Afterward, Teller went to Copenhagen , Denmark on a Rockefeller Fellowship to work under Niels Bohr . On February 26, 1934, he married Augusta Maria "Mici" Harkanyi († 2000) in Budapest, the sister of a friend from high school. The children Paul (born 1943 in Chicago , Illinois) and Susan Wendy Teller (born August 31, 1946 in Los Alamos , New Mexico) were born from the marriage.

Moved to the USA and turned to nuclear research

In Denmark he met the Russian physicist George Gamow . When Gamow got a position at George Washington University in Washington, DC, Teller followed him in 1935 and moved with his wife to the United States. At first Teller did research in quantum , molecular and nuclear physics . When he became a citizen of the United States of America in 1941, he mainly devoted himself to nuclear physics, both nuclear fission, discovered in 1938, and nuclear fusion.

Teller's most important work was probably the explanation of the Jahn-Teller effect , which describes the distortion in the geometry of the ligand field of some octahedral complex compounds along a spatial axis. He was also instrumental in the BET theory .

Due to his aversion to Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Teller worked on military research in the United States after the start of World War II . On the advice of the Hungarian aerodynamics researcher Theodore von Kármán , who also emigrated , he and his friend and German emigrant Hans Bethe developed a theory of the propagation of shock waves . Later this research on the role of gas in shock waves would prove very helpful.

Manhattan project

In 1938, Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann discovered the process of nuclear fission when uranium was bombarded with neutrons in Berlin . It quickly became clear that this process would release enormous amounts of energy. Teller received detailed information about the new discoveries in the field of atomic physics at the latest when Niels Bohr visited Washington in January 1939. In February 1939, Teller was informed by his friend Leó Szilárd that a large amount of neutrons was released during the fission of uranium . This seemed to give the possibility of a chain reaction, either in the form of a civilian use as an energy-supplying fuel reactor or as a military use in the form of a bomb. In June 1939 Teller moved from Washington to Columbia University in New York City to work there with Enrico Fermi and Szilárd on the construction of a nuclear reactor for energy generation.

About a month before Germany's attack on Poland on September 1, 1939 - the beginning of World War II in Europe - Szilárd wrote a letter addressed to President Roosevelt , in which the possibility of a uranium bomb being constructed in Nazi Germany was suggested. Szilárd wanted Albert Einstein to sign the letter to give it more weight. Since Szilárd did not have a driver's license, Teller drove him to Einstein's summer house on Long Island , where he signed the pre-formulated letter. Because of this letter, there was increased support for nuclear research by government agencies in the USA.

In 1942 Teller was invited to Robert Oppenheimer's summer planning seminar at the University of California at Berkeley , which later evolved into the Manhattan Project , with the aim of building an atomic bomb . A few weeks earlier, Teller had spoken to his colleague Enrico Fermi about the prospects for success of nuclear weapons , and Fermi had suggested that a weapon using fission could trigger an even greater nuclear fusion reaction. Although Teller had several reasons to believe that such a reaction could not physically work, he was fascinated by the idea and did not want to be satisfied with a simple atom bomb - which was not nearly fully developed at the time. In the sessions of the Manhattan Project, he spoke openly of the possibility of a fusion-based bomb, which he called the “super bomb” (later the hydrogen bomb ).

During the Second World War he worked in the department of theoretical physics in the then secret research laboratory in Los Alamos , New Mexico , and campaigned heavily for the development of a hydrogen bomb, which lost priority than the development of a pure one Nuclear fission bomb turned out to be very difficult. Because of his preference for a hydrogen bomb and his frustration at the appointment of Hans Bethe as director of the theoretical research department in his stead, Teller refused to participate in the calculations for the uranium bomb's implosion . This created tension with other researchers and the recruitment of more scientists to do this work. Among them was Klaus Fuchs , who was later identified as a Russian spy . Furthermore, Teller made himself unpopular with his neighbors and colleagues because of his nightly piano playing.

Nevertheless, he was instrumental in research into nuclear weapons, particularly in explaining the implosion. In 1946 Teller left Los Alamos and became a professor at the University of Chicago .

Work on the hydrogen bomb

When the Soviet Union detonated an atomic bomb in 1949, US President Harry S. Truman announced a rapid program to develop the hydrogen bomb . Teller then returned to Los Alamos in 1950 to work on the project. However, he did not become the head of the project, despite the fact that he and the Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam had submitted a proposal for its implementation. Teller quickly became impatient due to the slow development and insisted on hiring additional theorists . He accused his colleagues of lacking imagination, which worsened his relationship with the other researchers. However, his and other designs remained unsuccessful. Hans Bethe later expressed the conviction that if Teller had not pushed for an early test of a hydrogen bomb, its development through the Soviet Union would have been slower. This is u. a. based on the fact that the physicist Klaus Fuchs , a Soviet spy in the US nuclear weapons program, submitted many incorrect technical details that prevented a functioning hydrogen bomb. Soviet researchers who had worked on the hydrogen bomb later claimed that they realized that the initial plans for a hydrogen bomb were not feasible in this way and that they therefore developed their hydrogen bomb completely independently of the results of the espionage activity.

In 1950, calculations by Stanislaw Ulam and his colleague Cornelius Everett , which were confirmed by Enrico Fermi , showed that Teller's earlier assumption about the amount of tritium needed for the hydrogen bomb was too low. Even with a significantly higher amount of tritium, the loss of energy during the fusion process was too great to sustain the fusion. In 1951, after many years of fruitless work, Teller took an innovative idea from Ulam and developed the first workable design for a hydrogen bomb with several megatons of TNT explosive power. The individual contributions of the two researchers to the so-called Teller-Ulam design are controversial. Some of the more hostile scientists to Teller (such as J. Carson Mark ) suggested that without the help of Ulam and other scientists, Teller would never have come near a working hydrogen bomb. Others stressed Teller's leading role. As early as 1954, Hans Bethe spoke of Teller's stroke of genius with the invention of the hydrogen bomb. Also in 1997, Bethe repeated his view that the decisive breakthrough was achieved in 1951 thanks to Teller. In an interview, Teller himself said:

“I contributed; Ulam did not. I'm sorry I had to answer it in this abrupt way. Ulam was rightly dissatisfied with an old approach. He came to me with a part of an idea which I had already worked out and difficulty getting people to listen to. He was willing to sign a paper. When it then came to defending that paper and really putting work into it, he refused. He said, 'I don't believe in it.' ”

“I contributed to the solution, Ulam didn't. I'm sorry for having to answer this so hard. Ulam was rightly unsatisfied with an old approach. He came to me with part of an idea that I had already worked out but that no one wanted to hear. He was ready to put his name as an author on a scientific publication. But when it came to defending the draft publication and actually putting work into it, he declined. He said, 'I don't believe in it.' "

The breakthrough - the technical details are still secret - apparently was the separation of the weapon’s fission and fusion components and the use of the radiation generated by the fission to compress the fusion fuel before ignition. However, the compression alone would not have been sufficient; the other deciding factor - splitting the bomb into two phases - was thought to be entirely Ulam's. Furthermore, Ulam wanted to use the mechanical shock of the first phase to favor the fusion in the second, while Teller realized very quickly that the radiation of the first phase could do this faster and more efficiently. Some members of the laboratory (especially J. Carson Mark) later stated that the idea of using radiation for this purpose would probably have occurred to everyone involved in the physical process. Teller probably thought of it immediately, because he had already been working on the tests for Operation Greenhouse in the spring of 1951. In this test, the energy effect of a uranium bomb on a mixture of deuterium and tritium was examined.

Regardless of how the details of the Teller-Ulam design came about and who contributed which part, the scientists involved quickly realized that this would take the project that decisive step further. Even those members who had previously doubted the feasibility of a hydrogen bomb were now convinced that it was only a matter of time before both the US and the Soviet Union had weapons with an explosive power of several megatons. Oppenheimer, who faced the project hostile at first, described the idea as technically sweet ( technically beautiful ).

Although Teller was in charge of the design and had long been a proponent of the concept, he was not appointed director of the project, possibly due to his difficult personality. In 1952, Teller left the project and moved to the Livermore Department at the University of California at Berkeley, which was newly established at his urging . After the detonation of Ivy Mike on November 1, 1952, the first thermonuclear explosive device to be built according to the Teller-Ulam design, Teller became known to the public as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself was not present at the test - he said he was not welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds test site - and only saw the effects on a seismograph in the basement of a hall in Berkeley.

By analyzing the radioactive fallout , the Soviet researchers headed by Andrei Dmitrijewitsch Sakharov could easily have concluded that the design used compression as an important basis. However, Soviet researchers later denied that they were sufficiently organized at the time to be able to measure fallout data from US tests. Because of its secrecy , little information is available about the development of the bomb. Reports in the press attributed all of the development to Teller and his Livermore Laboratory, although it was actually developed in Los Alamos.

Some of Teller's colleagues were irritated by the fact that Teller seemed to get all the credit for a project to which he had contributed only a part, albeit a decisive one. This impression was also created by the book about the hydrogen bomb by Time magazine journalists James Shepley and Clay Blair, published in 1954 and interviewed by Teller. In its intention of supporting Ernest Orlando Lawrence and Enrico Fermi (the dish in Chicago attended when he was dying, and his advice caught) wrote dish then an article The Work of Many People ( The work of many ), published in the journal Science in February 1955 appeared and in which he made it clear that he had not developed the hydrogen bomb alone. In his memoirs, he would later remark that he had written a white lie ( white lie or hoax ) in this article - which implies that he probably believed that he alone deserved full credit for the development of the weapon. Teller was known to delve into projects that were theoretically very appealing, but hardly feasible in practice, such as the project of a super bomb . Bethe later said:

“Nobody will blame Teller because the calculations of 1946 were wrong, especially because adequate computing machines were not available at Los Alamos. But he was blamed at Los Alamos for leading the laboratory, and indeed the whole country, into an adventurous program on the basis of calculations, which he himself must have known to have been very incomplete. "

“Nobody will accuse Teller of having wrongly calculated his 1946 calculations, especially because there were no adequate calculating machines available in Los Alamos. But in Los Alamos he was accused of having led the laboratory - and indeed the whole country - into an adventurous program based on calculations whose blatant incompleteness he must have been aware of. "

During the Manhattan Project, Teller also advocated developing a uranium hydride- based bomb , although many of his fellow researchers believed that it would not work. In Livermore, Teller continued his work on this hydride bomb, which only ended in a dud . Ulam once wrote sarcastically to a colleague about an idea he had shared with Teller: “Edward is very excited about these possibilities; maybe that's an indication that they will not work. "Fermi once said that he knew other than disk no other monomaniac with various manias .

Oppenheimer controversy

In 1954 Teller testified against Robert Oppenheimer , the former director of Los Alamos and a member of the Atomic Energy Commission , during interrogation about Oppenheimer's safety rating. Oppenheimer had spoken out in favor of arms control , which is why the Committee on Un-American Activities , led by Senator McCarthy, interrogated him over concerns about national security. Teller's testimony led to further estrangement between him and his old colleagues in Los Alamos. Teller and Oppenheimer had already clashed several times in Los Alamos over questions of research into nuclear fission and nuclear fusion. During the interrogations, he was the only member of the scientific community that Oppenheimer called a "security risk". When asked by District Attorney Roger Robb whether he implied that “Dr. Oppenheimer was disloyal to the United States, "replied Teller:

“I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and a very complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof to the opposite. "

“I don't want to suggest anything like that. I know Oppenheimer to be a highly intellectually capable and very complex person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part to try to analyze his motives in any way. But I have always assumed, and still do now, that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I will continue to believe it until I see very conclusive evidence to the contrary. "

When asked whether he believed that Oppenheimer represented a "security risk", however, he replied:

“In a great number of cases I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer act - I understood that Dr. Oppenheimer acted - in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more. In this very limited sense I would like to express a feeling that I would feel personally more secure if public matters would rest in other hands. "

“In a number of cases, I saw Dr. Oppenheimer act - I understood that he acted - in a way that was increasingly difficult for me to understand. I totally disagreed with him on many things, and frankly his actions seemed confused and complicated to me. So I think that I would like to see the most fundamental interests of this country in the hands of someone I understand better and who I therefore trust more. In this limited sense I would like to express the feeling that I personally felt more secure when matters of public interest were in other hands. "

Teller also testified that Oppenheimer's view of the thermonuclear program appeared to be based more on the scientific feasibility of the weapon than on other considerations. He also said that Oppenheimer's management of Los Alamos had been a “very extraordinary achievement” both scientifically and administratively, and he praised its “very quick mind” and that it had “simply made a wonderful and excellent director”.

Nonetheless, he went on to detail the way in which he felt that Oppenheimer had impeded his (Teller's) efforts towards an active thermonuclear development program. He extensively criticized Oppenheimer's decision not to have put more effort into this question in the course of his career. Teller's most severe condemnation of Oppenheimer was the following statement:

"If it is a question of wisdom and judgment, as demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one would be wiser not to grant clearance."

"When it comes to measuring Oppenheimer's intelligence and judgment against his actions since 1945, I would say it would be wiser not to issue a clearance certificate."

Oppenheimer was then withdrawn from the necessary safety certification for sensitive military research. Teller's behavior was almost unanimously condemned by his fellow scientists, and from then on he was regarded by many as an informer and an unscrupulous careerist. This development can also be clearly seen in Teller's list of publications. Before 1952, he had contributed as an author to 84 scientific publications and he was the sole author of only seven. After 1952 he wrote 42 scientific publications alone and 20 together with co-authors. Many scientists now evidently avoided working closely with him. As a result, Teller began to surround himself with military and government officials. After the incident, Teller repeatedly denied that he wanted to harm Oppenheimer, and even claimed that he tried to exonerate him. However, evidence strongly suggests that this likely was not the case. Six days prior to his testimony, Teller met with an Atomic Energy Commission liaison officer and suggested that his testimony "deepen the allegations".

Nuclear technology and Israel

For around 20 years, Teller advised Israel on nuclear matters in general, and especially on hydrogen bomb construction . In 1952 Teller and Robert Oppenheimer had a long meeting with David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv and told him that the best way to accumulate plutonium was to burn natural uranium in a nuclear reactor. In addition, Teller was awarded the Harvey Prize of the Technion honored.

Political work

Teller was director and founding member (together with Ernest O. Lawrence ) of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory from 1958 to 1960 , then deputy director, as he also taught at Berkeley. He tirelessly advocated the nuclear bomb and advocated further research and nuclear weapon tests . Indeed, his lobbying against the legislative initiative to partially ban the testing of nuclear weapons was one more reason to quit his position as director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He spoke out against this law both in front of the US Congress and on US television.

After the Oppenheimer controversy, Teller was ostracized by much of the academic, scientific community. On the other hand, he was even more popular than before in military and conservative government circles. His support for American supremacy in science and technology made him a favorite with conservative politicians.

In addition to its traditional advocacy of nuclear power sources, a strong nuclear arsenal and systematic nuclear weapons testing program he participated in the development of safety standards for nuclear reactors and helped in the design of a reactor in which the meltdown would be hypothetically impossible: the so-called TRIGA reactor of the manufacturer General Atomics , which can still be found today in various research institutions.

In 1975 he retired and was then Director Emeritus of the Livermore Laboratory and also Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institute .

Teller was one of the strongest and most well-known proponents of research into civilian nuclear weapons explosions , also known by the name of the American project: Operation Plowshare ( Operation Ploughshare ). One of the most controversial projects he proposed was the use of a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to create a deep-water port more than a mile long and a half-mile wide to ship raw materials from the coal and oil fields near Point Hope , Alaska . In 1958 the American Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) accepted Teller's proposal. The project was named Operation Chariot . While the AEC surveyed the land at the planned location in Alaska and withdrew it from public use, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but failed to convince local government officials that the project was financially viable.

Other scientists criticized the project because of its potential danger to the affected wildlife and the indigenous Inupiat who lived near the area in question, and who did not hear about the plan from the official side until 1960. It also turned out that the port would not be navigable for nine months of the year due to the heavy ice formation. Eventually the project was abandoned in 1962 due to financial uncertainty and health concerns related to radioactivity.

In a similar experiment, which was also encouraged by Teller , a nuclear weapon explosion was supposed to enable oil production in the Athabasca oil sands in northern Alberta , Canada . The plan was approved by the Alberta government but prevented by the Canadian government under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker . In addition to his concerns about nuclear weapons in Canada, Diefenbaker was concerned that such a project could increase Soviet espionage activity on Canadian soil.

Three-Mile Island

In 1979 Teller suffered a heart attack , for which he blamed Jane Fonda : After the reactor accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant , the actress strongly opposed the use of nuclear energy during the presentation of her latest film . The film The China Syndrome , which is about an accident in a nuclear power plant, happened to be released a little over a week before the serious accident on Three-Mile Island and thus dealt with a current problem. In response to Fonda's efforts, Teller promoted the use of nuclear energy, which he believed was safe and reliable. He also wrote a two-page article for the Wall Street Journal entitled "I was the only victim of Three-Mile Island," which appeared in the July 31, 1979 issue appeared. The first paragraph of the article read:

“On May 7, a few weeks after the accident at Three-Mile Island, I was in Washington. I was there to refute some of that propaganda that Ralph Nader, Jane Fonda and their kind are spewing to the news media in their attempt to frighten people away from nuclear power. I am 71 years old, and I was working 20 hours a day. The strain was too much. The next day, I suffered a heart attack. You might say that I was the only one whose health was affected by that reactor near Harrisburg. No, that would be wrong. It was not the reactor. It was Jane Fonda. Reactors are not dangerous. "

“On May 7th, a few weeks after the reactor accident on Three-Mile Island, I was in Washington. I was there to refute the propaganda that people like Ralph Nader , Jane Fonda and their like are making in the media to scare people and turn them away from nuclear energy. I am 71 years old and I worked 20 hours a day. The burden was too much. The next day, I had a heart attack. You could say I'm the only person whose health was affected by the reactor accident near Harrisburg. But that would be wrong. It wasn't the reactor, it was Jane Fonda. Nuclear reactors are not dangerous. "

The next day, the New York Times criticized Teller in its editorial, noting that it was paid for by Dresser Industries . Dresser Industries had made one of the broken valves that led to the Three-Mile Island accident.

Strategic Defense Initiative

In the 1980s, Teller began a campaign for the later so-called Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), which was sometimes also called "Star Wars". The concept was, laser - and satellite technology to defend against Soviet ICBMs use. Teller tried to convince government agencies of his plan to develop a sophisticated satellite system that would use X-rays to launch enemy ICBMs , and won the support of US President Ronald Reagan . However, the matter later turned into a scandal when it turned out that the undertaking was technically not feasible. Teller and his partner Lowell Wood had deliberately downplayed the technical difficulties and possibly supported the dismissal of laboratory director Roy Woodruff , who wanted to investigate and correct this more closely. From this affair a joke developed that circulated in the scientific community: the unit of measurement for unfounded optimism is the "plate", a plate is so large that most observations have to be measured in nano or pico plates .

Several scientists pointed out the pointlessness of the project. Hans Bethe and the IBM physicist Richard Garwin analyzed the system in a Scientific American article and came to the conclusion that any supposed enemy could easily outsmart the defense system with suitable bait. Manfred von Ardenne is credited with the statement that the SDI system could be paralyzed by means of a few sacks of sand in the corresponding orbits. The project was restricted several times and ultimately not implemented. However, Teller was later bolstered by the Bush administration , which reinvigorated the missile defense program in the early 21st century; Critics called it the "son of Star Wars" in reference to SDI's nickname.

Attitude to the atomic bombs on Japan

Despite (or possibly because of) his reputation as a hardliner , Teller publicly stressed several times that he regretted the atomic bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II. He claimed that before the bombing of Hiroshima he had advertised Oppenheimer to demonstrate the new weapon to the Japanese high command and the Japanese people before it was used for the first time, before thousands of people would have to die in a "sharp operation" as a result. In discussions, "the father of the hydrogen bomb" used this quasi-anti-nuclear stance, arguing that nuclear weapons are very unfortunate but that the arms race is inevitable because of the "insubordinate nature of communism". With this argument, Teller also promoted projects like SDI, which he believed were necessary to ensure that nuclear weapons would never be used again (“Better a shield than a sword” was the title of one of his books on the subject).

However, there are indications that suggest the opposite. Teller had signed neither the petition of his Hungarian physicist colleague Leó Szilárd against the use of the bomb against Japan, nor the corresponding recommendation of the commission headed by Oppenheimer. In the 1970s, an old letter from Teller to Szilárd emerged, dated July 2, 1945:

“Our only hope is in getting the facts of our results before the people. This might help convince everybody the next war would be fatal. For this purpose, actual combat-use might even be the best thing. "

“Our only hope is to make people understand the results of our work. This would help convince everyone that the next war would be devastating. For this purpose, actual combat operations could even be the best option. "

Professor Barton Bernstein from Stanford University therefore considers Teller's claim that he spoke out against the use of the atomic bomb against Japan to be untrustworthy.

Late life and legacy

Scientific lifetime achievement

In the early years of his career, Teller made many important contributions in nuclear and molecular physics (including the theory of the hydrogen molecule ion), spectroscopy (Jahn-Teller and Renner-Teller effects) and surface physics . In nuclear physics, he expanded Fermi's theory of beta decay ( Gamow-Teller transition ) with George Gamow and, together with Maurice Goldhaber, formulated the theory of giant dipole resonance . The Jahn-Teller effect , named after Teller and Hermann Arthur Jahn , and the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory bear his name. Teller also made contributions to the Thomas-Fermi theory , the forerunner of density functional theory , now a standard method for calculating the properties of many-electron systems, especially in molecules and solids. In this context, he examined the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, for example in astrophysics or in nuclear weapon explosions. In 1953, together with Nicholas Metropolis and Marshall Rosenbluth , his wife Augusta H. Teller and Arianna W. Rosenbluth, Teller wrote an article that is considered the starting point for the application of Monte Carlo simulation in statistical mechanics .

public perception

Teller's vehement advocacy of nuclear weapons - especially since many of his wartime fellow researchers later expressed regrets about the arms race - made him a popular target and personification of the mad scientist . His Hungarian accent and thick dark eyebrows did their part. In 1991 he was one of the first to be awarded the satirical Ig Nobel Prize for “ lifelong efforts to change the meaning of the term peace as we understand it” ( lifelong efforts to change the meaning of peace as we know it ).

Model for “Dr. Strangelove "

It has been speculated that Teller was one of the inspirations for the eccentric, bizarre figure of the scientist Dr. Strangelove in Stanley Kubrick 's satire of the same name from 1964 (other inspirations are said to have been John von Neumann and RAND theorist Herman Kahn , rocket researcher Wernher von Braun and former US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara ). In a Scientific American interview in 1999, Teller responded angrily when asked about this character:

“My name is not a Strangelove. I don't know about Strangelove. I'm not interested in Strangelove. What else can I say? ... look. Say it three times more, and I throw you out of this office. "

“My name is not Strangelove. I don't know anything about Strangelove. I am not interested in Strangelove. What else can i say ... Look, if you say that three more times, I'll kick you out of the office. ) "

Critical voices and controversial appearances

The physicist and Nobel Prize winner Isidor I. Rabi once stated

"Without a plate it would have been a better world."

At an advanced age, Teller gave a lecture in the Frankfurt Volksbildungsheim . When asked whether the first atomic bomb would have been thrown on Germany if Germany could have delayed the end of the war, he replied in a similar manner: “No, the Germans were already too far in atomic research and we were not allowed to give them any advice or even help in the case of a dud. There was no such danger in Japan. "

During a broadcast of the Austrian television discussion group Club 2 with the title Radiant Future at the beginning of the 1980s, Teller - who was charged as the father of the hydrogen bomb - gave such a technocratic lecture about the devastating effect of the then much-discussed neutron bomb on people that the Swiss scientist Ursula Koch during the live discussion started crying. Der Spiegel later described Teller's appearance as that of a "gloomy Jahve ". According to one of the editors later, Koch had been specially invited because she was assessed as "stable" in the face of Teller's statements, even "if something terrible came".

Return to Hungarian roots

Even though Teller had left Hungary decades earlier, he never forgot his origins or his mother tongue. After the collapse of communism in Hungary in 1989, he visited his home country several times and followed the political developments very closely. During the 2002 election campaign in Hungary, Teller sent a letter to the national conservative political party Fidesz to assure them of his support.

death

Edward Teller died in Stanford on September 9, 2003 .

Honors

Teller was a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science , a member of the National Academy of Sciences (1948), a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1954) and the American Nuclear Society . He was honored with the Albert Einstein Award , the Enrico Fermi Prize and the National Medal of Science . He was also a member of the group of US researchers elected Person of the Year 1960 by Time Magazine . In 1992, on the occasion of his 84th birthday, the asteroid (5006) plate was named after him. Less than two months before his death, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush .

In 2008 Hungary issued a 5,000 forint silver commemorative coin on the 100th anniversary of its birth.

The Edward Teller Award is presented in his honor .

Interviews

- No burden of conscience in this regard (December 11, 1963), Günter Gaus in an interview with Edward Teller. In: Gaus, Günter What remains are questions. The classic interviews . Berlin: The New Berlin, 2000.

- Louder please! (André Behr and Lars Reichardt: SZ-Magazin in July 2000)

- "Heisenberg sabotaged the atomic bomb." In: Michael Schaaf: Heisenberg, Hitler and the bomb. Conversations with contemporary witnesses. Gütersloh 2018, ISBN 978-3-86225-115-5 .

Works

- Francis Owen Rice, Edward Teller, Kenneth W. Hedberg: The Structure of Matter. John Wiley and Sons, New York 1949.

- Outlook into the core age . Fischer, Frankfurt / M. 1959.

- Better a Shield Than a Sword. Perspectives on Defense and Technology . Free Press, New York 1987, ISBN 0-02-932461-0 .

- The dark secrets of physics . Piper, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-492-03299-0 .

- Energy for a new millennium. A story of energy from its beginnings 15 billion years ago to its present state of adolescence . Ullstein, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-550-07693-2 .

- Memoirs. A 20th. century journey in science and politics . Perseus Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-7382-0778-0 .

- The Pursuit of Simplicity . Pepperdine University Press, Malibu, Calif. 1981, ISBN 0-932612-11-3 .

- The situation of modern physics . West German Publishing House, Cologne 1965.

- The legacy of Hiroshima . Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf 1963.

literature

- William J. Broad: Teller's War. The Top-Secret Story Behind the Star Wars Deception. Simon & Schuster, New York 1992.

- Gregg Herken: Brotherhood of the Bomb. The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller. Henry Holt, New York 2002.

- Dan O'Neill: The Firecracker Boys . St. Martin's Press, New York 1994.

- Richard Rhodes : Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb . Simon and Schuster, New York 1995.

- Gary Stix: Infamy and honor at the Atomic Café. Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career . In: Scientific American . October 1999, pp. 42-43.

- Stanley A. Blumberg: Edward Teller, giant of the golden age of physics. A biography . Scribner, New York 1990, ISBN 0-684-19042-7 .

- Peter Goodchild: Edward Teller. The real Dr. Strangelove. HUP, Cambridge, Mass. 2004, ISBN 0-674-01669-6 .

- Hans Mark (Ed.): Energy in Physics, War and Peace. A Festschrift celebrating Edward Teller's 80th birthday . Kluwer, Dordrecht 1988, ISBN 90-277-2775-9 .

- Hans Mark, Sidney Fernbach (eds.): Properties of matter under unusual conditions: in honor of Edward Tellers 60th birthday , New York: Interscience 1969

- Michael Schaaf: Heisenberg, Hitler and the bomb. Conversations with contemporary witnesses. Diepholz 2018, ISBN 978-3-86225-115-5 (in it: "Heisenberg sabotaged the atomic bomb." A conversation with Edward Teller )

- István Hargittai : The Martians of science - five physicists who changed the twentieth century. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-517845-9 .

- István Hargittai: Judging Edward Teller: A Closer Look at One of the Most Influential Scientists of the Twentieth Century. Prometheus Books, 2010, ISBN 978-1-61614-221-6 .

- Konrad Lindner: A nuclear physicist tells. Edward Teller between Leipzig and Livermore. Editor: Rector of the University of Leipzig. University of Leipzig 1998. 40 pages.

Documentaries

- Thomas Ammann: The Struggle for Freedom: Six Friends and Their Mission - From Budapest to Manhattan, MDR documentary, 2013

Web links

- SB Libby, MS Weiss: Edward Tellers Scientific Life . In: physics today . June 3, 2004

- G. Gamow, E. Teller: Selection rules for β-disintegration. In: Physical Review . Volume 49, 1936, p. 895 Abstract

- Some of Teller's Los Alamos reports : Los Alamos Reports and Publications

- Literature by and about Edward Teller in the catalog of the German National Library

- Edward Teller Is Dead at 95; Fierce Architect of H-Bomb The New York Times, September 10, 2003

- DIED: Edward Teller - 2003 Mirror No. 38

- Freeman J. Dyson: EDWARD TELLER January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003 , Biographical Memoir, National Academy of Sciences, 2007 (pdf; 163 kB)

- The University of California IN MEMORIAM Edward Teller - University Professor, Emeritus

- Edward Teller in the dictionary of persons

- Edward Teller Biography: Father of the Hydrogen Bomb

- Edward Teller in: Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008

- Wolfgang Burgmer: January 15th, 1908 - Birthday of the physicist Edward Teller WDR ZeitZeichen from January 15th, 2013 (podcast)

swell

- ↑ The "father of the hydrogen bomb" is dead. Süddeutsche Zeitung, accessed on October 9, 2013 .

- ↑ The father of the hydrogen bomb. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 25, 2013 ; Retrieved on October 9, 2013 (interview in SRF Switzerland on October 12, 1980). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ “ I have always considered that description in poor taste. "Teller, Memoirs , p. 546.

- ↑ Academy of Achievement: Edward Teller Interview ( Memento of the original from May 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Teller in an interview on 'achievement.org/' - “ In the spring of 1933, it became very clear that no Jew had a place in Germany. ”

- ↑ 1. An early interest in numbers , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 3. Two typewriters and a mirror , 4. Why I didn't become an experimental physicist , 5. A favorite professor and the law of nines , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 10. Unhappy high school memories , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 7. Learning the piano , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories', Teller also later used the piano as a hobby: see the 82-year-old Teller plays ( memento of the original from October 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: Der Archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. the 1st movement from the moonlight sonata

- ↑ 12. University and the Eötvös prizes and 13. First success as a scientist , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 14. Going to university in Germany , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 17. Permission to become a physicist , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 18. The inspiration of Herman Mark , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 19. A lack of enthusiasm for Sommerfeld , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 20th Jumping off the moving train and 21st Losing my foot but meeting by Lossow , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ E. Teller: About the hydrogen molecule ion. In: Journal of Physics . 1930, volume 61, pp. 458-480.

- ↑ Helmut Rechenberg, Gerald Wiemers (Ed.): Werner Heisenberg. Reports of reports and examinations for doctorates and habilitation theses (1929–1942), Berlin: ERS-Verlag, 2001, pp. 43–45. 25. Professor Kobe (Part 1) and 26. Professor Kobe (Part 2) , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 35. Becoming an assistant of Eucken and Franck , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 50. Terrible feelings and Hitler is made Chancellor of Germany , Teller in a video on 'Web of Stories'

- ↑ 51. Moving to England , Teller in a Video on 'Web of Stories'

- ^ A b c d Freeman J. Dyson: EDWARD TELLER: 1908-2003 . National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC, 2007 (pdf; 163 kB)

- ^ Yuli Khariton and Yuri Smirnov : The Khariton version . In: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists . Volume 49, Issue 4, May 1993, pp. 20-31. online full text at Google Books

- ^ Bengt Carlson: How Ulam set the stage ( Memento of September 28, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). In: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists . Volume 59, Issue 4, July / August 2003, pp. 46–51.

- ↑ Hans Bethe: Testimony in the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer . 1954.

- ↑ Hans Bethe: J. Robert Oppenheimer . In: Biographical Memoirs . Volume 71 (National Academy of Sciences, 1997), p. 197.

- ^ A b Stix, Gary: Infamy and honor at the Atomic Café: Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career . In: Scientific American . October 1999, pp. 42-43. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ Yuli Khariton and Yuri Smirnov: The Khariton version ( Memento from September 28, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). In: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists . Volume 49, Issue 4, May 1993, pp. 20-31.

- ^ Blair, Shepley, The Hydrogen Bomb: The Men, the menace, the mechanism , New York: McKay 1954. According to Teller Memoirs , 2001, p. 403, the book was the actual reason for Teller to write the Science article.

- ↑ Sōshichi Uchii : Review of Edward Teller's "Memoirs" . In: PHS Newsletter . Volume 52, July 22, 2003.

- ^ Teller, Memoirs, 2001, p. 407

- ↑ Bethe, Hans A .: Comments on The History of the H-Bomb. (PDF 311 kB) In: Los Alamos Science 3 (3): p. 47. 1982, accessed on March 20, 2013 (English, pdf).

- ^ A b Gregg Herken: Brotherhood of the bomb: the tangled lives and loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer . Henry Holt & Company, 2002, ISBN 0-8050-6588-1 (on Fermi on p. 25, on Ulam on p. 137)

- ^ A b c Edward Teller: Testimony in the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer . April 28, 1954.

- ↑ Steven Shapin: Megaton Man (Review of Edward Teller's "Memoirs"). In: The London Review of Books . April 25, 2002.

- ^ Edward Teller in Israel To Advise on a Reactor. December 6, 1982, accessed July 8, 2013 .

- ^ Karpin, Michael: The Bomb in the Basement . Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York 2005, ISBN 0-7432-6595-5 , pp. 289-293.

- ↑ Gábor Palló: The Hungarian Phenomenon in Israeli Science . In: Hungarian Academy of Science . 25, No. 1, 2000. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ umanitoba.ca: Nuclear dynamite

- ^ I was the only victim of Three-Mile Island . In: Wall Street Journal . July 31, 1979, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ Edward Teller: Better a Shield than a Sword. Perspectives on Defense and Technology . The Free Press, New York 1987, p. 57.

- ↑ Essay Review-From the A-Bomb to Star Wars: Edward Teller's History Better A Shield Than a Sword: Perspectives on Defense and Technology Technology and Culture , Volume 31, No. 4, October 1990, p. 848.

- ↑ Teller About the Hydrogen Molecule Ion , Zeitschrift für Physik, Volume 61, 1930, pp. 458-480

- ↑ G. Gamow, E. Teller: Selection rules for the disintegration , Phys. Review, Vol. 49, 1936, pp. 895-899

- ↑ M. Goldhaber, E. Teller: On Nuclear Dipole Vibrations , Phys. Review, Volume 74, 1948, p. 1046

- ↑ H. Jahn, E. Teller: Stability of polyatomic molecules in degenerate electronic states 1 , Proc. Roy. Soc. A 161, 1937, 220-235

- ↑ Stephen Brunauer, PH Emmett, Edward Teller: Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers . In: Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1938, 60 (2), pp. 309-319

- ↑ Stephen Brunauer, Lola S. Deming, W. Edwards Deming, Edward Teller: On a Theory of the van der Waals Adsorption of Gases. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society. Juli 1940, 62 (7), pp. 1723-1732

- ↑ N. Metropolis, AW Rosenbluth, MN Rosenbluth, AH Teller, E. Teller: Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. In: The Journal of Chemical Physics. Volume 21, Number 6, June 1953, pp. 1087-1092, doi : 10.1063 / 1.1699114 .

- ↑ This quote has been assigned to Rabi by several news sources, cf. u. A. Observer review: Edward Teller by Peter Goodchild . However, there are also reputable sources that assign it to Hans Bethe, e.g. B. in the appendix to the epilogue in Herken 2001 ( MS Word ; 52 kB).

- ↑ Always a tightrope walk. Der Spiegel, 20/1982, May 17, 1982, p. 257.

- ↑ "What are you talking about today?" derstandard.at, March 12, 2008.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Teller, Edward |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Teller, Eduard (deS); Teller, Ede (huS) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Hungarian-American physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 15, 1908 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Budapest , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 9, 2003 |

| Place of death | Stanford , California |