Behzād

Kamāl od-Din Behzād -e Herawi ( Persian کمالالدینْ بهزادِ هروی, DMG kamāl ud-dīn bihzād-i hiravī ; born between 1460 and 1466 in Herat ; d. 1535 / 1536 in Tabriz ) was a Persian painter. Even during his lifetime he was considered the most important representative of Persian miniature painting . Hence the title of Master ( Persian استاد ostād ) awarded. Its common short nameBehzād(Persian بهزاد) means "better-born".

Life

Behzād's life dates are uncertain. The Persian, Mughal and Ottoman testimonies to this, which were written down during his lifetime and also in the decades after, should be viewed critically. They are often not free from a mystification and praise of Behzād as the most experienced painter of his time, who can even be compared with Māni , who is described as the epitome of a painter in Persian sources , and they do not aim to convey precise dates. A coherent biography is not handed down in any of these testimonies.

Behzād probably came from Herat. His year of birth is unknown. Orphaned at an early age, he is said to have been adopted and trained in Herat by the Timurid court painter and calligrapher Amir Ruḥollāh Mirak Chorāsāni (Mirak Naghghāsch).

As the earliest employer in Herat, the Timurid ruler Sultān Ḥoseyn Mirzā Bāygharā and his minister Mir ,Ali Schir Nawāʾi are named, with whom Behzād worked as Mirak's subordinate employees. At the court of this art-loving sultan he came into contact not only with important painters such as Mawlānā Walī Allah, but also with the poet Jāmi , who belonged to the Sufi order of the Naqshbandi . Jami introduced Behzad into this order and influenced Behzad's thinking, but also his painting.

After the Sultan's death, Behzād is said to have worked for Mohammed Scheibani Khan in Bukhara .

Herat remained Behzād's place of work even after the Safavid Shah Ismail I came to power in 1510. Here he was appointed head of the royal library (Kitābkhāneh-yi Humāyūn) and of all the artists and craftsmen of the entire Safavid Empire who were involved in the production of the manuscripts.

The fact that Behzād had two siblings can be assumed, since he is said to have taught descendants of them - the calligrapher Rostam-ʿAlī and the painters Moḥebb-ʿAlī and Moẓaffer-ʿAlī - in Tabriz. He may have been recruited there by Ismail I in 1522. It is more likely, however, that Behzād did not come to Tabriz until 1529. It is certain that he worked there at the court of Tahmasps I and - as in Herat - was head of the royal library and picture workshop. According to Dust Mohammads, he died in Tabriz. A chronogram gives 942 d. H. (1535/36) as the year of death. His resting place is a double grave in Tabriz, in which Behzād was buried next to the Persian poet and Sufi Kamāl Chodschandi.

Works

Most of Behzād's works were created in Herat, only a few in Tabriz. They can be assigned to four categories:

- Illustrations in books with a simple narrative structure and in books with mystical content that require a deeper interpretation from the painter

- Illustrations - often double-sided, depicting imaginary scenes and scenery independently of any text

- Illustrations of historical events based on contemporary reports

- Portraits and Afterlife Events

Behzād's earliest pictures were taken during his apprenticeship with Mirak. The usual training consisted of copying and imitating the works of his teacher and older masters such as Mir Khalil and Mawlānā Walī Allah. This was followed by an occasional collaboration with Mirak or with other painters on the illustration of books within the Herat workshop, before completely own pictures were used. Some early pictures from 1480 onwards bear Behzād's signature or tapes that name Behzād as a painter or copyist. Illustrations in a divan from 1481 by Amir Chosrau and an album sheet from 1482 are already typical of Behzād's style.

Today's art historians unreservedly recognize four illustrations of a copy of Saadis Bustān from 1488/89 stored in Cairo as independent and personal works . Behzāds have been incorporated into these miniatures for signatures believed to be authentic.

The attribution of further miniatures in Persian albums and copies of famous poems, possibly signed and unsigned by someone else's hand, is based on the one hand on contemporary sources and on the other on comparisons of styles and materials in modern art history. These are the illustrations for a copy of Sharaf al-Din Ali Yazdis Zafarnama from 1436, a copy by Fariduddin Attar's Mantiq al-taye from 1483, a copy from ʿAlī Schīr Nawā'īs Khamsa from 1485, a copy from Saadis Gulistan from 1486 and a copy of Nezāmis Khamsa from 1495/96. Another copy of Nezāmis Khamsa from 1442 was accompanied by some illustrations attributed to Behzād around 1490. Some of these miniatures follow Heratian models from the first half of the 15th century in terms of structure and details.

Many single sheets are also believed to be works by Behzād. An example of an ink drawing on which the last important Timurid ruler, Sultān Ḥoseyn Mirzā Bāygharā, is shown on horseback shows that it is difficult to attribute them. On his clothing there are signatures that cannot be clearly assigned to Behzād himself.

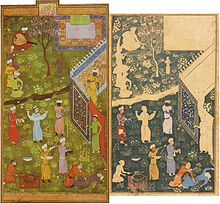

Pictures (selection)

Illustrations

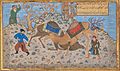

The fight between Iskander ( Alexander the Great ) and Dara ( Dareios III ). Behzād's signature is in the upper left between the two text fields: suvvarahu al-ʿabd Bihzād . Miniature from 1520.

Portraits on single sheets

Gentile Bellini or Costanzo da Ferrara: Portrait of a Scribe , around 1480. This picture, made in Istanbul, was often copied and imitated. Compare the picture next door.

Portraits within miniatures

Late works

The picture made in Tabriz around 1530 was often copied and imitated. The inscription contains a reference to the Koran ( sura 88 : 17) and to Behzād's age of seventy.

Stylistic features

Behzād's personal style is evident in the four signed miniatures of the Cairo Bustān manuscript, which can almost certainly be ascribed to him. They serve as a style-critical comparison with other pictures from Herat, also with the unsigned pictures of his contemporaries, with whom he shares some of the characteristics typical of the time. The linear accuracy and the balanced composition seem more important than the spatial representation. Buildings are represented as flat surfaces and bear calligraphy and meticulously drawn decorative patterns. Behzād is nevertheless assigned a noticeable sense of space. His figures seem to move with ease. They are differentiated according to age and physical appearance and often appear to be portrayed. Behzād's pictures are drawn and painted with great care. Her intricately executed compositions are praised, in which every line and every color nuance is intended to create a feeling of harmony and balance. His iconography includes not only courtly scenes, but also everyday things - often of symbolic significance - such as funerals, collecting firewood and erecting buildings.

Behzād's portraits, on the other hand, have a significantly different style and follow Italian models with their individual expression, gestures and physicality.

Students and close co-workers

Since Behzād initially worked as a learner and employee and later as a manager and teacher of a workshop, there was always a mutual influence of the members of the respective workshop. A split of hands has not yet succeeded in many of the pictures. Even pictures with Behzād's signature can either have been created with the collaboration of other artists or come entirely from them. Especially after Behzād's relocation to Tabriz, many pictures that stylistically point to Behzād were painted by his employees under his supervision. In this way he paved the way for a new generation of painters, while he himself painted less and less - perhaps also because of a progressive visual impairment.

Students and employees in Herat (selection)

Shah Muzaffar, Hadschī Muhammad (student of Shah Muzaffar), Dervish Muhammad (student of Shah Muzaffar), Abd al-Razzaq, Qasim Ali Chichre-Gushay (comparable to Behzād in artistic rank), Shayk-Zadeh Mahmud Muzahhib (moved to Bukhara) , Mullah Yusuf.

Students and staff in Tabriz (selection)

Sayyid Mir Musavvir (temporarily head of the workshop), Nizam al-Din Sultan Muhammad, Sayyid Aqa Jalal al-Din Mirak al-Husayni Isfahani (temporarily head of the workshop), Muhammad (Qadimi), Mirza Ali (son of Nizam al-Din Sultan Muhammad), Mir Sayyid Ali (son of Sayyid Mir Musavvir), Moẓaffer-ʿAlī (Behzād's nephew), Moḥebb-ʿAlī (Behzād's great-nephew), Abdal-Samad (together with Moẓaffer-ʿAlī the foundation stone for the Mughal painting workshop), Shah Tahmasp (probably already in Herat Behzād's pupil and later instructed by Nizam al-Din Sultan Muhammad), Dust Muhammad b. Sulayman al-Herawi the calligrapher.

Reception and significance in art history

Behzād's works were seen much more often than those of his contemporaries during his lifetime as excellent and trend-setting. Shortly after his death, Behzād was famous as nadir al-asr (rarity of the age), and sar amad-i musavviran (the [leading] head among illustrators). However, critical objections to his style of portrait painting were also raised, which of course show that Behzād was perceived as a master with his own style. Overall, there was a tendency to regard Behzād as a binding model for the simultaneous and subsequent Persian, Mughal and Ottoman miniature painting. As a result, his originally innovative stylistic features had to be retarded and were defensive against the “Franconian”, realistic, perspective-based and human influences in painting in the Christian West.

In the book art of the Islamic cultural area, Behzād became a mythologically exaggerated mediator of Persian miniature painting, which was initially influenced by Chinese and Mongolian art.

Since around 1900, first European and subsequently also international art scholars have been intensively concerned with Behzād. One reason for this could be that he could be seen as a named artist and representative of the Persian tradition, which was largely shaped by anonymous painters. This also made him a favorite in the art trade. Behzād's appreciation was evident, for example, in the fact that he was compared to Western painters such as Hans Memling , Hans Holbein the Elder and Raffael, as well as Jean Fouquet and François Clouet .

Only recently have Behzād's life and work, his artistic origins and his influence on subsequent generations been extensively presented and his pictures discussed. Worth mentioning are the works of Ebadollah Bahari (1996) and Michael Barry (2004) as well as the large number of individual studies and essays by David J. Roxburgh, in particular his treatise on Behzād and authorship in Persian painting (2000).

literature

Persian sources

- Behzād's pictures and inscriptions on pictures in which Behzād is named as the author or which are attributed to Behzād

- Preface to a lost album compiled by Behzād (dībācha-yi muraqqaʿ-i Ustād Bihzād) , communicated by Khwandamir.

- Babur Mirza : Baburnama (1506)

- Decree (nischān) appointing Master Kamāl od-Din Behzād as head of the royal library (1519 or 1522) communicated by Khwandamir.

- Behzād's petition to Tahmasp I or Ismail I (between 1510 and 1522)

- Khwandamir: Habib al-siyar fi akhbar afrad al-bashar (1523-1524)

- Dust Muhammad: Foreword to the Bahram Mirza album . (1544)

- Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat : Tarikh-i Rashidi (1546)

- Mir Sayyid Ahmad: Foreword to the Amir Ghayb Beg album (around 1556)

- Qadi Ahmad. Gulistan-i Hunar (1606)

Overall representations

- Qamar Aryan: Kamaluddin Bihzad . Tehran 1930.

- Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996.

- Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465–1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004.

Representations in lexica (selection)

- Jonathan M. Bloom, Sheila S. Blair: Bihzad '. In: "The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1, Oxford [inter alia]: Oxford Univ. Press, 2009.

- Richard Ettinghausen : Bihzad . In: Encyclopaedia of Islam . Vol. 1, Leiden 1960, p. 1212 f.

- Priscilla Soucek: Behzād, Kamāl-al-Dīn . In: Encyclopædia Iranica . Vol. 4, p. 115.

Individual aspects (selection)

- Thomas W. Arnold: Bihzad and his Paintings in the Zafarnamah Manuscript . London 1930.

- Fredric Robert Martin: Les miniatures de Behzad dans un manuscrit persan daté 1485 . Munich: Bruckmann 1912.

- Muḥammad Muṣṭafā: Persian miniatures: works by d. Behzad school. From collections in Cairo . Baden-Baden: Klein 1959.

- David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol. 17, 2000.

Individual evidence and explanations

- ↑ David J. Roxburgh: The Persian Album 1400–1600: from dispersal to collection. New Haven [u. a.]: Yale Univ. Press, 2005, p. 204.

- ↑ This time span was calculated. Two dates were used for this: Behzād's death year 1535/36 and the year in which Behzād painted the "Fighting Camels". On the inscription of the "Fighting Camels" Behzād describes himself as a seventy-year-old. Ebadollah Bahari dates the camel image to around 1530 and comes to around 1460 for the year of birth. Michael Barry assumes that the camel picture was taken in the year Behzād died, and cites Budaq-i Qazwini, who states that Behzād was about seventy when he died in 1535, and therefore comes to the year of birth 1465. See Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad . Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. S. XII. Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465–1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004, p. 134 f u. 155-159.

- ↑ a b Dust Muhammad: Foreword to the Bahram Mirza Album (TSK H. 2154). English translation in: Wheeler McIntosh Thackston (Ed.): A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art. Cambridge, Mass. ; Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture; 1989, p. 347. PDF 1.21 MB , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Bihzad . In: Jonathan M. Bloom, Sheila S. Blair (Eds.): The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture . Oxford [u. a.]: Oxford Univ. Press, 2009.

- ↑ Wheeler Thackston MacIntosh: Album prefaces and other documents on the history of calligraphers and painters . Suffering a.]: Brill, 2001, p. 42, footnote.

- ^ A b David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol.XVII, 2000, p. 121.Download PDF 5.56 MB , accessed on November 20, 2016.

- ↑ See Khwandamir's Habib al-siyar . Volume 3 of his universal history from 1523/24. English translation in: Wheeler McIntosh Thackston (Ed.): A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art. Cambridge, Mass. ; Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture; 1989, p. 226.Download PDF 11,115 kB , accessed on November 20, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d Priscilla Soucek: Behzād, Kamāl-al-Dīn . In: Encyclopædia Iranica . Vol. 4.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. p. 43.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. IX et al. 48.

- ↑ Accordingly, Qadi Ahmad called him Maulānā Behzād in 1606 . See Calligraphers and Painters. A treatise by Qāḍī Aḥmad, son of Mīr-Munshī (circa AH 1015 / AD 1606) . In: Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers . Vol. 3, No. 2, Washington 1959. U. a S. 147. Download PDF 3.47 MB , accessed on November 20, 2016.

- ↑ a b Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 184-187.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. p. 179.

- ↑ The fact that Behzād - as Qazi Ahamd Qummi reported in 1596 - was buried in his native city of Herat at the foot of the mountain Koh-i Mukhtar can be regarded as a legend. See Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465–1535) . Paris: Flammarion 2004, p. 159.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. p. 47.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 42 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 52-59.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 59 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 100-112.

- ↑ Today: Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins U. Garrett Lib.

- ↑ Today: New York, Met. 63.210.

- ↑ Today: partly Oxford, Boleian Lib. Elliott 287, 317, 339, 408, and partly Manchester, John Rylands U. Lib. Turk 3.

- ↑ Today: Houston, TX, A. & Hist. Trust col. ex-Paris, Rothschild priv. col.

- ↑ Today: London, BL. Add. MS. 6810.

- ↑ Today: London BL. Add. MS. 25900.

- ↑ Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465-1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004, pp. 110-112.

- ↑ Picture and explanation online at Museum of Fine Arts , Boston . Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol. XVII, 2000, p. 139 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 52-54.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 88-90.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 108-111.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 146-148.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. P. 134 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 126-128.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 198 f.

- ^ Discussion of the image in David J. Roxburgh: Discorderly Conduct ?: FR Martin and the Bahram Mirza Album . In: Muqarnas . Volume 15, pp. 33-41.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 174 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. p. 50 u. 173.

- ↑ Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465-1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004, p. 144.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 174-177.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. p. 174.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 171-173.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. p. 197.

- ↑ Bahari (1996) and Barry (2004) consistently date the picture to "c. 1490". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the painting is located, dates it to "circa 1480". Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 94 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 155 f.

- ↑ Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465-1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004, p. 166 f.

- ^ Adel T. Adamova: The Iconography of a Camel Fight . In: Muqarnas . Volume 21, Leiden: Brill 2004, pp. 1-4. Download PDF 1.09 MB , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 215 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. P. 216 f.

- ↑ General Egyptian Book Organization , Cairo, Adab Farsi 908.

- ↑ Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465–1535). Paris: Flammarion 2004, p. 152.

- ↑ Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465-1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004, p. 154.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 220 f.

- ^ David J. Roxburgh: Prefacing the Image. The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran . Leiden et al., Brill 2001, p. 27 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996. pp. 221-229.

- ↑ The representation of Persian art by authors of the 16th century is examined in detail in David J. Roxburgh: Prefacing the Image: The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran. Leiden (et al.): Brill, 2001.

- ↑ In: Badāye ʿal-waqāyeʿ by Wāṣefi.

- ↑ In: Manaqhib-i Hunarvaran by Mustafa Ali.

- ↑ Cf. Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur's criticism in Bāburnāme , c. 1529, quoted and discussed in: David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol. XVII, 2000, p. 191 u. 121.

- ↑ See also Zaynhuddin Wassifi's review of his time in Herat in an anecdote he shared in 1538. In English translation in Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465–1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004, p. 163 f.

- ↑ Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Preface to the Bahram Mirza album in A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art . Cambridge, Mass., 1989, p. 347.Download from archnet.org , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ↑ See Orhan Pamuk : My name is red . Frankfurt am Main, 2003. The book deals extensively with the iconoclastic dispute in the Ottoman Empire around 1590, in which Behzād's miniatures play an important role as models for the images of the old school.

- ^ P. de Bruijn: Bihzad meets Bellini. Islamic Miniature Painting and Storytelling as Intertextual Devices in Orhan Pamuk's My Name is Red . In: Persica. Vol. 21, pp. 9-21.

- ↑ On the influence of Chinese painting cf. the unfinished drawing of a dervish in the Bahram Mirza album attributed to Behzād. (TSK, H. 2154, fol.83b), illustrated and reviewed in David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol. XVII, 2000, pp. 125 ff and in David J. Roxburgh: The Persian Album 1400–1600: from dispersal to collection. New Haven [u. a.]: Yale Univ. Press, 2005, p. 284 f.

- ^ David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol. XVII, 2000, p. 119 and p. 141, note 9 with detailed information.

- ^ Nasri Amir Kia Sanaz: A Comparative Study of the Concept and Role of the Man in the Works of Kamla al-Din Bihzad and Raphael. In: Naghsh Mayeh . Summer 2012, Volume 5, No. 11, pp. 31-44.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996.

- ↑ Michael Barry: Figurative Art in Medieval Islam and the Riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465-1535) . Paris: Flammarion, 2004.

- ^ David J. Roxburgh: Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting . In: Muqarnas , Vol.XVII, 2000.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996, pp. 181-184.

- ^ A b David J. Roxburgh: Prefacing the Image. The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran . Leiden et al., Brill 2001, p. 24.

- ^ In English translation in Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Babur Mirza. Baburnama . In: A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art . Cambridge, Mass., 1989, pp. 247-278. Downloaded from archnet.org , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996, p. 184 f.

- ↑ Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996, p. 235.

- ↑ In English translation in Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Khwandamir. Habib al-siyar . In: A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art . Cambridge, Mass., 1989, pp. 101-236. Downloaded from archnet.org , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ↑ In English translation in Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Dost-Muhammad. Preface to the Bahram Mirza album . In: A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art . Cambridge, Mass., 1989, pp. 335-350. Downloaded from archnet.org , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ^ David J. Roxburgh: Prefacing the Image. The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran . Leiden et al., Brill 2001, p. 39 f.

- ↑ Excerpt in English translation in Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Mirza Muhammad-Haydar Dughlat. Tarikh-i Rashidi . In: A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art . Cambridge, Mass., 1989, pp. 357-362. Downloaded from archnet.org , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ^ David J. Roxburgh: Prefacing the Image. The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran . Leiden et al., Brill 2001, p. 34.

- ↑ In English translation in Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Mir Sayyid-Ahmad. Preface to the Amir Ghayb Beg album . In: A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art . Cambridge, Mass., 1989, pp. 353-356. Downloaded from archnet.org , accessed November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Quotations from it in: Ebadollah Bahari: Bihzad. Master of Persian Painting. London [u. a.]: Tauris, 1996, p. 41.

- ↑ This work corresponds to a version published in English translation: Calligraphers and Painters. A treatise by Qāḍī Aḥmad, son of Mīr-Munshī (circa AH 1015 / AD 1606) . In: Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers . Vol. 3, No. 2, Washington 1959. Behzād is mentioned and discussed several times therein (see index). Download PDF 3.47 MB , accessed November 20, 2016.

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Behzād |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bihzad, Behzad; Kamāl ud-Dīn Beḥzād Herawī |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Persian artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | between 1460 and 1466 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Herat , Khorasan , Timurid Empire (today Afghanistan ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1535 or 1536 |

| Place of death | Tabriz |