Revenge tragedy

The revenge tragedy is a specific form of tragedy, at the center of which stands the revenge of the protagonist for an actual or supposed injustice.

The term revenge tragedy was first used around 1900 by the American Shakespeare researcher Ashley Horace Thorndike to classify a genre-specific group of dramas from the late Elizabethan and Jacobean epochs between 1580 and 1620, which are a special form of classical antiquity Take tragedy as a model.

While in this the tragic essentially arises from the so-called "height of fall" of the noble tragic hero, the Elizabethan-Jacobean revenge tragedy primarily deals with the problem of atoning for an injustice without acting injustice itself. The hero fails because of the indissolubility of this contradiction: In order to help justice to victory, he - now himself guilty - must die while carrying out his vengeance .

The revenge tragedy was one of the most popular types of drama on English stages in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The action was constructed on the basis of the motive for revenge and the avenger mostly acts against the resistance of society, sometimes in conflict with his own conscience.

The popularity of this form of drama in Elizabethan theater is based in particular on the public interest at the time in the contradicting views on the problem of private revenge.

In the anarchic age of the Wars of the Roses , blood revenge was still widespread and generally accepted in society, but resistance on the part of the Church increased in the period that followed. At the same time, private revenge was seen by the strengthening central state in the 16th century as a violation of its monopoly of violence and a threat to public order.

In contrast to the increasingly clear official condemnation of private vengeance, however, a code of vengeance was widespread, especially in aristocratic circles, which had a tradition of exercising their own rights for centuries and saw vengeance as a matter of honor, in which blood vengeance was a normative obligation in certain constellations . According to this conception, such an obligation to commit blood revenge existed especially when state authorities refused or were unable to atone for a crime. While it was not possible to produce conclusive evidence of a crime, a special understanding of the avenger was shown when he felt obliged to avenge the murder of a close blood relative, his wife, his lover or a close friend.

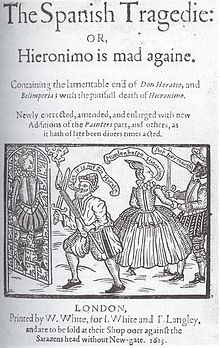

The specific pattern of action of this Elizabethan form of revenge tragedy with an ambivalent assessment of revenge, the spirit of revenge as a chorus and the "game within the game" to unmask the murderer was first developed by Thomas Kyd with his play The Spanish Tragedie , which was published between 1582 and Created in 1592. The special stage and genre historical significance of this work is expressed not only in the ten print editions of the work between 1592 and 1633, but also in countless adaptations and intertextual allusions, adoptions or references in other pieces by various authors of the time.

The style-forming effect of Kyd's model on subsequent revenge tragedies is shown above all in dramatic motifs and structural elements such as the appearance of a spirit warning of revenge, the cleverly engineered intrigue and deception in the implementation of vengeance, the hesitant action of the avenger, the game in the game , the madness of unbearable pain, the only feigned madness, the type of Machiavellian villain as an opponent of the protagonist or the atoning suicide of the avenger, which - partly adopted by Kyd from the Italian novella literature - then became established conventions of the Elizabethan revenge tragedy .

In Kyd's Spanish Tragedy , the rapid change in the plot between sensational, action-filled scenes and lingering scenes marked by a gloomy mood or foreboding is particularly effective . The connection of the motif of revenge and the associated acts of violence with the motif of romantic love characterizes the exemplary form of Kyd's revenge tragedy.

Compared to earlier attempts to dramatize the motif of revenge in the schematic framework of the structure of morality , Kyd succeeds for the first time in fully exploiting the dramatic potential of this new form of tragedy. In a prototypical way, Kyd's work already contains all the characteristic elements of the new genre : At the beginning or before the beginning of the action, a murder is committed that goes unpunished for various reasons. The protagonist of the drama is closely related to the murder victim; mostly he is the only one who receives knowledge of the crime that was committed in a context in which it is not possible for the most varied of reasons to obtain atonement for what has happened. Against this background, the protagonist is obliged to take revenge himself in order to restore justice. With this commitment, both the personality of the protagonist and his relationship to the other characters in the drama change. The problem of revenge can cause a deformation of the psychological structure and the restriction or suspension of the critical judgment of the protagonist to the point of insanity, since the moral obligation to blood revenge is no longer clear according to the applicable social norms and values. With the knowledge of the deed and the decision to take revenge despite a conflict of values, the protagonist becomes increasingly isolated. This forces him to cunning and pretending, as he does not receive any social support, but has to reckon with social resistance.

Such a basic pattern of revenge tragedy enables an unusually large number of dramatic variations in the further development. For example, the act of revenge can be shifted to a wide variety of social milieus and expanded almost indefinitely through parallel acts. Likewise, the social or emotional relationships between the dramatic characters of the murder victim, the avenger and the victim of revenge can be varied. The public's need for drastic stage actions could be satisfied through effective design or increased cruelty in the exercise of revenge; Likewise, the figure of the avenger could be drawn both as a hero and as a villain and the sympathies of the audience could be directed either to the avenger or the victim of revenge by focusing accordingly.

In his prototype of the revenge tragedy, Kyd also develops a repertoire of stage conventions such as the apparition of ghosts, the disguise of the avenger, the delaying of vengeance or the use of the game in the game to unmask the murderer or to carry out vengeance.

The formative influence of Kyd's basic type of revenge tragedy can be seen, for example, in contemporary plays such as William Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus (premiered between 1589 and 1592), John Marston's Antonio's Revenge (1599-1601), Thomas Middleton's The Revenger's Tragedy (1607) or George Chapman's Revenge of Bussy d'Ambois (around 1610).

A forerunner for the common appearance of the spirit of the murdered and the allegorical figure of vengeance at the beginning of the Spanish tragedy can be found in the ancient tragedy Thyestes attributed to Seneca . In The Spanish Tragedie, Kyd is also inspired by other elements from Seneca's tragedies, for example in his highly stylized linguistic rhetoric of the drama, the long conversations with himself or the stichomythic dialogues, but in contrast to Seneca, he brings the many blood and atrocities in line with the Elizabethan theater practice immediately for performance.

Shakespeare's Hamlet is probably the best-known revenge tragedy, which was typologically influenced by Kyd's work not only in its central motif, but also in numerous other dramatic details : the title character is obliged to avenge the murder of his father, that of his brother and current king was killed. A direct model for Shakespeare's drama is assumed in research to be an unspecified original Hamlet , written by Kyd . In spite of the recognizable adoption of the conventional elements of the revenge tragedy such as the revenge order, delay in execution, social isolation of the protagonist and tension with the fellow actors, Shakespeare changed their arrangement and assigned them new functions. The dramatic focus here is less on the transformation of the protagonist into avenger and the spectacular exercise of revenge, but primarily on the presentation of a sensitive, reflective person who is subjected to an emotional, moral and intellectual endurance test that takes him to the edge of his utter psychological endurance Destruction leads.

In several other works by Shakespeare, revenge appears as a secondary motif, for example in the dramas Richard III , Romeo and Juliet , Julius Caesar , Macbeth , Othello and Coriolanus .

In the further development of the type of revenge tragedy, revenge is more and more clearly condemned with didactic intent from different perspectives in subsequent stage works, for example in Thomas Middleton's and William Rowley's A Fair Quarret (1616) or Philip Massinger's Fatal Dowry (1619). At the same time, elements of romance are increasingly interwoven with the motif of revenge. The dramatic interest in revenge as a conflicted problem is waning; it is hardly at the center of the plot as the primary objective of the protagonist. Instead, revenge appears increasingly as a plausible motive, among other things, for shaping the structure of relationships between the dramatic characters, with revenge as a motive for action being increasingly attributed to the villain, through which a tragic course of action can be brought about.

The renowned English scholar and literary scholar Wolfgang Weiß attributes the public's growing disinterest in the conventional revenge tragedy to the fact that private vengeance in the form of duels was increasingly regulated and thus defused by a strict code in aristocratic circles, so there was no danger to them state exercise of rights represented more. In addition, according to Weiß, the bourgeois classes, who, due to their Christian orientation, showed little understanding for revenge as a motive for action, were able to enforce their social norms and values more and more confidently.

Individual evidence

- ↑ See the corresponding entry Revenge tragedy in the Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ↑ See John Kerrigan: Revenge Tragedy: Aeschylus to Armageddon . Oxford University Press. Oxford 1996. See also the relevant review by Linda Charnes. In: Shakespeare Quarterly , Vol. 48, No. 4 (Winter, 1997), pp. 501–505, here p. 501, online at jstor under [1] . Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ↑ See in detail Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of the Shakespeare period. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 148ff. (online as a PDF file [2] ). See also Wolfgang Weiß: The Revenge Tragedy . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare manual. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), p. 66.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 151f. (online as a PDF file [3] ).

- ↑ See in detail Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 150ff. (online as a PDF file [4] ). See also Wolfgang Weiß: The Revenge Tragedy . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare manual. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), pp. 65f. See also the corresponding entry Revenge tragedy in the Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved April 19, 2020. See also “Let me curse, rage, scream” . Contribution by Ruth Fühner on November 8, 2008 on Deutschlandfunk . Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ↑ Cf. Wolfgang Weiß : Die Rachetragödie . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare manual. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), p. 66. See also the corresponding entry Revenge tragedy in the Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved April 19, 2020. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 464, and in detail Wolfgang Weiß : Das Drama der Shakespeare-Zeit. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 150 - 157. (online as a PDF file [5] ) Cf. also Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's Dramen on the typological assignment of Shakespeare's Hamlet to the genre of revenge tragedy . Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel 1996, 2nd, revised. Edition 2001, ISBN 3-8252-1907-0 , pp. 177f.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of the Shakespeare period. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 157. (online as PDF file [6] )