Miles christianus

Miles christianus ( Latin "Christian soldier", also Miles Christi or Miles Dei , "soldier Christi", "soldier of God", also "Militia Christi") is a term for the view of a Christian as a fighter, warrior or warrior of Jesus Christ in of the world.

New Testament and early Christianity

Tradition does not foresee a warlike change in conditions for the disciples of Jesus or a violent bringing about of a messianic redeemer. Nevertheless, the letters of the Apostle Paul and the Stoa, which comprehends life as militia spiritualis, evoke echoes of soldierly or militant imagery. This also includes weapons in the figurative sense, such as the "weapons of justice" or the "weapons of light" ( Rom 13.12 EU ), the "armor of faith and love" ( 1 Thes 5.8 EU ) or the “Armor of God”; the “girdle with truth, the shield of faith” against the “fiery projectiles of evil”, the “helmet of salvation” and the “sword of the spirit” ( Eph 6,13-17 EU ); as well as the spiritual warrior, soldier or fighter ( 2 Cor 10,3–6 EU ), ( 2 Tim 2,3f. EU ), who lives in the world but does not fight with the weapons of this world. The first letter of Clement , which does not belong to the canon, describes all Christians as fighters of Christ: "Be contentious, brothers, and zealots - for that which serves for salvation!" (1 Clem 37).

Furthermore there is at Origen labeling of Christian ascetics as "soldiers of Christ". With the writings of Tertullian , Cyprian and the acts of martyrs , the combative metaphor spread widely into Christian Latinity ( sacramentum, statio, vexilla, signum, donativum ). Thus, Facundus of Hermiane Athanasius described the great as Magister militiae Christi , so that in the 6th century the Benedictines finally formulated a spiritual principle programmatically: "We have to prepare our hearts and bodies for battle in order to be able to obey the divine directives."

In the early church, however, participation in the military was often out of the question for Christians because of the imperial cult associated with it (see also: Conscientious objection in late antiquity ).

middle Ages

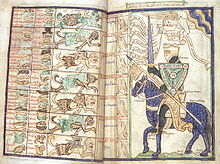

In the 10th and 11th centuries, the interpretation of the Christian warrior changed from the spiritual metaphor to the literal "Christian knight" and "soldier of God". Initially, the knight exercised a secular function of violence in the God's Peace Movement as an armed guarantor of peace for the church and the faithful.

In the course of the emerging monastery reforms and the investiture dispute , Pope Gregory VII felt compelled to concentrate the term Militia christiana and the Pauline speech of the “good fighter of Christ” on the armed forces of the Milites sancti Petri . The papacy now availed itself of the nobility, who were supposed to enforce secular Roman interests using military force.

In his call for the first crusade in 1095, Pope Urban II gave the soldiers the honorable designation Milites Christi . This went hand in hand with the institutionalization of rites for the "defense and protection [...] for churches, widows and orphans, for all servants of God against the rage of the heathen", whereby the church sword blessing and the secular sword line merged ritually. The Milites christiani now established themselves in the spiritual orders of knights ( Johanniter , Deutscher Orden ), to protect pilgrims and to fight against unbelievers, whereby the militarization of the orders goes back to the Templars , confirmed with the Bull Militia Dei in 1145 , to which among others the Order of the Brothers of the Sword counted.

St. Bernhard (1091–1153) made a distinction in his writing Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae on the re-establishment of the Templar order between Militia saecularis ("secular warriors") and Militia Christi ("Christian warriors").

The cult of so-called soldier saints handed down by some martyrs of the early church spread in the Middle Ages. In the lives of saints like Mauritius , Sebastian , Georg and Johanna von Orleans , virtues that were partly spiritual and soldierly came together.

Modern times

Discredited by the experience of the Crusades and by the incipient secularization of secular rule, the image of Miles christianus literally faded . The spiritual orders of knights shifted their work to the charitable area.

St. Ignatius applied principles of military discipline to the formulation of his retreat and the establishment of the Society of Jesus . "Whoever in our society, which we would like to have named after the name of Jesus, fight for God under the flag of the cross and only want to serve the Lord and his representative on earth, the Roman Pope" [...]. On the other hand, the thought occurs in allegories or in songs like Vorwärts Christi Streiter or Mir, speaks Christ, our hero , in pietism , the revival movement and also in the structures of methodism in the 19th century. The salvation army and the legionaries of Christ are considered to be a striking contemporary variety of the application of soldierly metaphor .

Remarks

- ↑ Mt 26.52 EU ; Lk 9.53-55 EU

- ^ Regula, Prologue, 40

- ↑ Quoted in Weddige, p. 176.

- ^ Beginning of the Formula Instituti

literature

- Andreas Wang: The miles Christianus in the 16th and 17th centuries and its medieval tradition: A contribution to the relationship between linguistic and graphic imagery. Lang, Bern; Frankfurt (M.) 1975, ISBN 3261009330 .

- Robert R. Bolgar: Hero or Anti-Hero? The Genesis and Development of the Miles Christianus. In: Concepts of the Hero in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Papers of the Fourth and Fifth Annual Conferences of the Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, State University of New York at Binghamton, May 2-3, 1970, May 1-2, 1971. Edited by Norman T. Burns and Christopher J. Reagan . State University of New York Press, Albany 1975, pp. 120-146.

- Jeffrey Ashcroft: Miles Dei - Goths Knight. Konrad's Rolandslied and the Evolution of the Concept of Christian Chivalry. In: Forum for Modern Language Studies 17 (1981), pp. 146-166.

- Gerd Althoff : Nunc fiant Christi milites, quid dudum extiterunt raptores. On the origin of chivalry and knight ethics. In: Saeculum 32 (1981), pp. 317-333.

- Sabine Krüger: Character militaris and character indelibilis. A contribution to the relationship between miles and clericus in the Middle Ages . In: Institutions, Culture and Society in the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Josef Fleckenstein on his 65th birthday. Edited by Lutz Fenske, Werner Rösener , Thomas Zotz , Sigmaringen 1984, pp. 567-580.

- Hilkert Weddige: Introduction to German Medieval Studies. 6th edition, Munich 2006. Chapter: The miles christianus. Pp. 175-177 . (Preview on Google Books)

- Hanns Christoph Brennecke: Militia Christi. In: Religion Past and Present. Concise dictionary for theology and religious studies , 4th edition, Tübingen 2008, pp. 1231–1233.