Sankt Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest

The Sankt Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest was a Benedictine - Abbey in St. Georgen in Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis in Baden-Wuerttemberg in southern Black Forest .

history

The foundation of the St. Georgen Monastery

At the beginning of the investiture controversy (1075–1122), certainly one of the most striking turning points in Europe's medieval history, the foundation of a Benedictine monastery falls on the "vertex of Alemannia" ( vertex Alemanniae ) in the Black Forest: the monastic community in St. Georgen, at the source Located on the Brigach , was a result of the merging of the Swabian nobility and the church reform party, impressively represented by the monastery founders Hezelo and Hesso from the Reichenau Vogt family and the abbot and monastery reformer Wilhelm von Hirsau (1069-1091). The brothers Ulrich, Mangold and Ludwig von Sigmaringen are named as donors. Instead of the Upper Swabian Königseggwald , which was initially envisaged , Wilhelm St. Georgen was encouraged to choose the place where the monastery was founded. The history of the Black Forest monastery began with the settlement of St. George by Hirsau monks in the spring and summer of 1084 and the consecration of the monastery chapel on June 24, 1085.

Manorial rule, bailiwick, and Roman freedom

Initially a Hirsau priory , then an independent abbey (1086), the rise of St. George to one of the most important monasteries in south (west) Germany in Hirsau began in the time of Abbot Theogers (1088–1119) . Until the middle of the 12th century, donations, purchases and exchanges of land and rights increased the monastery property considerably and thus created the material basis of monastic existence. The rulership of goods, property complexes, dependent peasants, income and rights, also over parish churches and monasteries, which extends over Swabia and Alsace and is condensing in the area between the Neckar and Danube, secured the supply of the monks who, among other things, in liturgy and prayer for salvation commemorated the monastic benefactors.

The monastery and monastery property were (theoretically) protected by the Vogt , the secular arm of the abbot and monastic convent. In the early years of St. Georgen's existence, the monastery founder Hezelo († 1088) and his son Hermann († 1094) held the bailiwick. It is unclear since when exactly the Zähringer dukes took over the bailiwick, which is clearly documented in this office for the first time in 1114. According to late medieval tradition, this happened immediately after Hermann's murder. An important step on the way to the Zahringian bailiwick was certainly the privilege of Urban II of 1095, which guaranteed the convent free election of bailiffs. Duke Bertold II has been in a kind of protective function towards the monastery since 1094, although Ulrich (I) von Hirrlingen as the second husband of Hermann's widow before 1111 and again after Bertolds III. 1122-1124 had made claims. After the Zähringers died out in 1218, the bailiwick fell to King Friedrich II of the Staufers (1212 / 1215-1250).

For the respective owners of this legal institute, there was income from monastery ownership and opportunities to influence St. Georgen and the transition there over the Black Forest, because protection in a certain sense meant rule over the monastic community. The provisions of the privileges of March 8, 1095 and November 2, 1105, which the abbey obtained from Popes Urban II (1088–1099) and Paschal II (1099–1118) and which were considered to be constitutional, were of little use Securing the monastery of libertas Romana , the " Roman freedom " guaranteed. The latter included the subordination of the monastery to the papacy with papal protection, free election of abbots and disposal of the monastery over the bailiwick. It conditioned the classification of the monastic individual community in the Catholic Church with the suppression of noble church law and bailiwick and with securing the monastic existence against episcopal claims. The libertas Romana was so important for the Black Forest monastery that it - together with the monastery property and the monastic rights - was to be confirmed again and again by the popes in the high Middle Ages.

Reform center of Benedictine monasticism

One of these high medieval papal privileges was the document of Pope Alexander III. (1159–1181) for St. Georgen dated March 26, 1179. From it we can see the importance of the Black Forest monastery as a reform center of Benedictineism during the 12th century in Alsace, Lorraine, Swabia and Bavaria. The document names a large number of communities that were then closely related to the Black Forest Monastery, i.e. h .: St. Georgen submitted to pastoral care or in the context of the monastery reform or were established from St. Georgen. The convents in office Hausen (1102) and the monastery Friedenweiler in Friedenweiler (1123) were St. Georgen-ups and included as priories (outstations) for possession of the Black Forest monastery, the monastery of St. Marx (1105) as the monastery in the Alsatian Lixheim the monastery Lixheim (1107), the Ursprunging nunnery (1127) or the “cell of St. Nicholas” in Rippoldsau (before 1179). The St. Georgen monks exercised a spiritual supervision over the nunneries Krauftal (1124/30) and Vargéville (around 1126) as well as the monastery St. Wolfgang (Engen) (1133), while the Benedictine monastery Ottobeuren (1102), the monastery Admont ( 1115, Admonter Reform), the St. Ulrich and Afra monastery in Augsburg (before 1120), the male monasteryChecking (1121) and the Mallersdorf monastery (1122) received abbots and / or reform impulses from St. Georgen. We must not forget that the St. Georgen Monastery was created under Hirsauer's influence, and that it was itself part of the Hirsau reform. We can still see that St. George's reform effects must have been considerable in the first third of the 12th century, during the time of Abbots Theoger and Werner I (1119–1134), while a phase of stagnation occurred in the second half of the century.

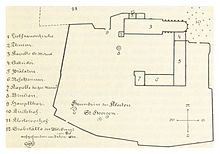

Hirsauer and St. Georgen monastery reforms meant the shift towards a stricter Benedictine way of life with a cluniac orientation. The idea of asceticism, an elaborate liturgy, the emphasis on duty and obedience when monitoring the activities of the monks and with harsher punishment for offenses belong here. The basis was the Regula Benedicti , the monastic rule of Benedict of Nursia (* approx. 480 - † 547). The abbot elected by the monks was in charge of internal and external management. The monks who formed the convent owed him obedience. There were also other monastery offices such as provost , dean , waiter , thesaurary , teacher or porter . The monks were committed to the common life, the Vita communis . Monk's vows, celibacy, poverty and a strictly regulated daily routine in the cloister's monastery buildings, which were shielded from the outside world, corresponded to this way of life. The cloister was used for meditation, the refectory and the dormitory for eating and sleeping together. Farm buildings and guest houses connected the monastic community with the outside world.

St. Georgen in Staufer times

In parallel to the more or less close relations with the papacy , the relationship with the German kings became increasingly important in the 12th century. It is worth remembering the turn of St. George to kingship, to King Heinrich V (1106–1125) in the vicinity of the bailiff's dispute with Ulrich von Hirrlingen. At that time the ruler confirmed u. a. in a diploma of July 16, 1112 of the monastic community the papal privileges of Urban II and Paschal? II. As well as the St. Georgen property at Lixheim. Lixheim also had the document of the Hohenstaufen emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa (1152–1190) from the year 1163. It was the time of the so-called Alexandrian papal schism (1159–1177), that church split in which the emperor's party and the counter-popes against the already mentioned Alexander III. stood. St. Georgen probably belonged largely to the Staufer side and received the above-mentioned privilege from Pope Alexander III only after the end of the schism through the Peace of Venice (July 24, 1177) . The extinction of the Zähringer , the St. Georgener Klostervögte, in 1218 brought - as mentioned - the bailiwick to the Staufer Friedrich II. In a document from December 1245 the emperor confirmed the document of his predecessor Heinrich V , not without to refer to the Staufer Bailiwick and the rights derived from it. Sometime between 1245 and 1250 Friedrich transferred the bailiwick as an imperial fiefdom to the Counts of Falkenstein , which they exercised until the 15th century - mostly to the detriment of the monastery.

The late Staufer period also initiated the economic and spiritual-religious decline of St. George. Aspects of this development were: the fire disaster of 1224, which destroyed the monastery - the new building was consecrated in 1255 -; In 1295 a chapel was donated by the Lords of Burgberg ; the decline of monastic discipline and monastic education; Loss of goods and rights through alienation, sale and mismanagement; internal unrest in the monastery convent - u. a. should the abbot Heinrich III. (1335–1347) had been murdered by his successor Ulrich II (1347, 1359). Only at the turn of the 14th to the 15th century brought under the reforming abbot Johann III. Kern (1392–1427) a reorientation of monastic life and thus a change for the better.

Empire and monastery in the late Middle Ages

Papal privileges for the St. Georgen monastery have also been handed down to us from the late Middle Ages - for the last time Pope Martin V (1417–1431) confirmed all freedoms and rights to the monastic community on January 17, 1418 at the Council of Constance - but the relationships did to the German kings and emperors for the Black Forest monastery an incomparably greater importance. Paradoxically, this was a consequence of the “Roman freedom” already explained: The reform monastery was neither an imperial abbey nor was it at the disposal of a noble family. The St. Georgen abbot was not an imperial prince, the Black Forest monastery was only imperial in the sense that he repeatedly succeeded in maintaining relations with the kingdom. This happened through the granting of royal privileges, most recently at the Worms Reichstag Emperor Charles V (1519–1558) on May 24, 1521.

Behind the approach to kingship was the demarcation from the monastery bailiffs, whose influence on the monastery and monastery area (i.e. St. Georgen and the surrounding area with Brigach, Kirnach, Peterzell) increased as part of the late medieval territorialization , while St. Georgen itself increased declined in importance and the monastery was in a spiritual and religious decline, despite the fact that it still owned significant land. The Falkensteiner bailiffs were followed by the counts and dukes of Württemberg, who acquired half of the bailiwick in 1444/1449 and the entire bailiwick in 1534. The year 1536 brought about a turning point with the establishment of the Württemberg state sovereignty over St. Georgen and the introduction of the Reformation, which essentially called the existence of the monastery into question. The imperial estate of St. George, as it was particularly evident in the participation of the monastery in the imperial registers of the 15th century, now gave way to country residency , the Catholic monastery and its monks found a new home in the Austro-Habsburg town of Villingen , while St. Georgen established a community with Protestant monastery rules under Protestant abbots (1566).

(Catholic) monastery of St. Georgen in Villingen in the early modern period

Soon after its creation, the St. Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest owned properties in Villingen and on the Baar. St. Georgen house ownership in the city is first attested to in 1291, is also recorded in the oldest Villingen civic register (1336) and can also be found in the more recent civic registers. Associated with this was the Villingen citizenship for the monastic community. The St. Georgener Pflegehof , which was located in the city and had an important role as the headquarters for the monastery property on the Baar, was the so-called Abt-Gaisser-Haus today , based on the north-western city wall, and was built in 1233/1234.

The events of the Reformation in the Duchy of Württemberg and in St. Georgen (1536) then led to the relocation of the monastic community from Brigach (via Rottweil ) to Villingen, which was dominated by the Habsburgs (1538), where the monks used the nursing court as a place of residence. With the exception of interruptions after 1548 and during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), Villingen remained the home of the monastery; the monastery inmates came to terms with the conditions in the city. On December 1, 1588, the convent of the Georgskloster concluded a contract with the local citizens on the rights and obligations of the spiritual community in Villingen, and the nursing yard on the city wall was expanded and redesigned again from 1598. When, after the end of the Thirty Years' War, the Catholic monks in the Georgskloster in Villingen had no hope of being able to return to St. Georgen, a four-storey convent house with sacristy, chapter house, refectory and library was built between 1688 and 1725 or 1756 The baroque monastery church was built, and a grammar school was connected to the monastery from around 1650.

The last abbots of the St. Georgen monastery until secularization were supposed to reside in the baroque monastery complex in Villingen. There were always problems with the city in which the Catholic monks had found shelter - e. B. 1774/1775 about the preservation of the Benedictine high school - but on the whole they got along. There were also disputes with the Austrian government. The abbots Hieronymus Schuh (1733–1757) and Cölestin Wahl (1757–1778) carried the title of imperial prelate, which met with resistance in 1757/1758, since the monastery was under Austrian sovereignty and was under Austrian protection and protection. But the matter was left on its own in the following years, but a newly elected abbot should notify the sovereign of his election and formally recognize his patronage. After that, Anselm Schababerle (1778–1806) was elected abbot of the Georgskloster only once. His term of office was under the sign of the French Revolution (1789) and secularization (1806).

The Georgskloster in Villingen came to an end in 1806. It was initially a Württemberg commission that inventoried the property of the monastery in Villingen on the basis of the Peace of Pressburg on October 26, 1805. This was followed on July 25, 1806 by the formal dissolution of the monastic community, which at that time consisted of the abbot, 24 priest monks and a lay brother. Assets worth over 150,000 guilders ended up in the Württemberg kingdom after the resolution of secularization: monastery inventory, furniture, books and cattle were brought to Württemberg, many of which were also sold on the spot. This all happened in great haste until August 5th, since the city of Villingen had already fallen to the Grand Duchy of Baden on July 12th, in accordance with the Rhine Confederation Treaty . With the handover of Villingen to Baden on September 12th, almost only empty monastery buildings came to the new owner. h .: Church, old prelature, grammar school, office, fruit box, as well as the rights to tithes and interest attached to the monastery. What was left were the books in the monastery library including a number of medieval manuscripts, a clock with carillon and the Silbermann organ . Most of the monastery documents, including the medieval and early modern documents, were brought to Karlsruhe. Abbot Anselm Schababerle and the monks were compensated with pensions and pastoral positions, including Franz Sales Wocheler .

(Evangelical) monastery in St. Georgen in the early modern period

After the adoption of the Württemberg monastery order (1556) and the death of the Catholic abbot Johannes V. Kern (1566), the Württemberg Duke Christoph (1550–1568) felt compelled to appoint Severin Bertschin (1566–1567) as the first Protestant abbot in St. Georgen to use. The Protestant monastery became the center of the St. Georgen Monastery Office, the former monastery area in the Württemberg state, even if its abbots were increasingly restricted in their administrative tasks compared to the bailiff in the following decades and soon only took on representative and pastoral functions. Visitations (decreed by the Duke) such as those of 1578 were used to monitor the monastery.

The Protestant predicant convention was no longer the size of the Catholic monastic community. Four lay brothers stayed behind in St. Georgen when Abbot Johannes Kern and the Catholic monks left the Black Forest monastery in 1566. Although novices were subsequently accepted into the evangelical community, the population of the monastery remained small, also when measured against the manorial income that the spiritual community was entitled to.

The monastery was also populated by students from the St. Georgener Klosterschule (grammar school), which had been established in accordance with the monastery rules of 1556. When the first teacher, the Preceptor Johannes Decius , arrived in St. Georgen on July 11, 1556, lessons could begin. a. Latin, partly Greek and Hebrew was taught. Bible readings and five church services with Latin chants supplemented the regular daily routine. In 1562 nine monastery students passed their exams, in 1580 the "Instruction why our Closters should behave towards S. Jeorgen uff dem Schwarzwald Amptmann" was written. On September 21, 1595, the teaching institute was closed again due to excessive costs. The last eight students came to Adelberg in the local monastery school of the Adelberg monastery , the two teachers from St. Georgen came to the Tübingen monastery.

The return of the Catholic monks to St. Georgen in autumn 1630 interrupted the Württemberg-Protestant monastery until 1648. Until 1630, the Protestant abbot Ulrich Pauli (1624–1630) was still in office; it was not until 1651 that Johannes Cappel (1651–1662) was appointed again as a Protestant monastery director. Andreas Carolus was probably the last of the Protestant abbots to reside in St. Georgen. Since 1679 superintendent in Urach, in 1686 he took over the management of the monastery in the Black Forest town. On the occasion of his appointment, Carolus confirmed in a document to recognize the castvogtei and patronage of the Württemberg duke, to represent the monastery as a state in the Württemberg state parliaments and to exercise preaching and church service according to the principles of the Protestant denomination. In particular, the provisions regarding the bailiwick and umbrella make it clear that the St. Georgen Monastery and the associated monastery office were not fully integrated into the Württemberg state rule even after the Thirty Years' War and the Peace of Westphalia .

The abbots who followed Carolus no longer stayed in St. Georgen, they were only titular abbots of a community whose buildings had been largely destroyed and uninhabitable since 1633. And so the topography of the monastery site was determined from the 2nd half of the 17th century by the new buildings of the office building, fruit store, rectory and gatekeeper house. From 1806 there were no longer any Protestant abbots at the St. Georgen monastery. In 1810 St. Georgen became Baden.

Finally, as part of the Napoleonic reorganization, Villingen also became part of Southwest Germany in 1805, and one year later it became part of Baden. Now the monastery suffered the fate of secularization. Monastic inventory came to Stuttgart, while the people of Baden ordered the abolition of the monastic community and the takeover of the remaining monastic property (1806).

Decay of the monastery buildings

During the Thirty Years' War, the Catholic monastery under Abbot Georg Michael Gaisser was able to hold its own for a few years (1629–1632) in St. Georgen, but the war led to the destruction of the monastery church and buildings on October 13, 1633 by fire. The monastery in St. Georgen was not rebuilt afterwards, the Catholic monastic community remained limited to Villingen. The remains of the monastery fell into disrepair after secularization. After the great fire in the town in 1865, the already dilapidated monastery was used as a quarry for the reconstruction of St. George.

Abbots of St. Georgen

additional

The monastery is named for the Sankt Georgen sermons .

literature

- Karl Theodor Kalchschmidt: History of the monastery, the city and the parish of St. Georgen in the Baden Black Forest . Heidelberg 1895, reprint St. Georgen / Schwarzwald 1988.

- Romuald Bauerreiß : St. Georgen in the Black Forest, a reform center of southeast Germany in the beginning of the 12th century . In: Studies and communications on the history of the Benedictine order and its branches . Volume 51, Munich 1933, p. 196.

- Bartholomäus Heinemann: History of the city of St. Georgen in the Black Forest . Freiburg i.Br. 1939.

- Heinrich Büttner: St. Georgen and the Zähringer . In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine . Volume 92 (NF 53), 1940, pages 1-23.

- Eduard Christian Schmidt: The Benedictine monastery of St. Georgen in the Black Forest 1084–1633, a subsidiary of Hirsau; Depicted on the basis of the sources and the excavations in summer 1958 . Stuttgart 1959.

- Hans-Josef Wollasch: The beginnings of the St. Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest. To develop the historical uniqueness of a monastery within the Hirsau reform (= research on the history of the Upper Rhine region . Volume 14). Freiburg i.Br. 1964.

- Erich Stockburger: St. Georgen - Chronicle of the monastery and the city (edited by city archivist Dr. Josef Fuchs). St. Georgen 1972.

- Josef Adamek and Hans Jakob Wörner: S [ank] t Blasien in the Black Forest: Benedictine monastery a. Jesuit College; History, meaning, shape (= Great Art Guide; Vol. 56). Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7954-0599-8 .

- Villingen City Archives (ed.): Diary of Abbot (Georg) Michael Gaisser of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Georg in Villingen 1595–1655 . 2 volumes (Volume I: 1621–1635, Volume II. 1636–1655). 2nd Edition. Villingen 1984.

- 900 years of the city of St. Georgen in the Black Forest 1084–1984 . Festschrift. Edited by the city of St. Georgen, St. Georgen 1984.

- Christian Schulz: God's judgment or human error? The diaries of the Benedictine abbot Georg Gaisser as a source for the war experience of religious during the Thirty Years' War . In: Matthias Asche, Anton Schindling (ed.): The judgment of God. War experiences and religion in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in the age of the Thirty Years War . Münster 2001. 2nd edition 2002, pages 219–290.

- Michael Buhlmann: How St. George came to St. Georgen (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 1). St. Georgen 2001.

- Michael Buhlmann: St. Georgen and Southwest Germany up to the Middle Ages (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , part I = Vertex Alemanniae . Book 2). St. Georgen 2002.

- Michael Buhlmann: Foundation and beginnings of the St. Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , part II = Vertex Alemanniae . Book 3). St. Georgen 2002.

- Michael Buhlmann: Manegold von Berg - Abbot of St. Georgen, Bishop of Passau (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 4). St. Georgen 2003.

- Michael Buhlmann: The document of Pope Alexander III. for the St. Georgen monastery (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 5). St. Georgen 2003.

- Michael Buhlmann: Manegold von Berg - Abbot of St. Georgen, Bishop of Passau: Sources and Regesten (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 6). St. Georgen 2003.

- Michael Buhlmann: Abbot Theoger von St. Georgen (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , part III = Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 7). St. Georgen 2004.

- Michael Buhlmann: The Popes in their relationship to the medieval monastery of St. Georgen (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , part IV = Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 8). St. Georgen 2004.

- Michael Buhlmann: The German kings in their relationship to the medieval monastery of St. Georgen (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , part V = Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 9), St. Georgen 2004.

- Michael Buhlmann: Ownership, manorial rule and bailiwick of the high medieval monastery of St. Georgen (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , part VI = Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 11), St. Georgen 2004.

- Michael Buhlmann: The Tennenbacher Güterstreit (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , Part VII = Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 12). St. Georgen 2004.

- Michael Buhlmann: The Lords of Hirrlingen and the St. Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 15). St. Georgen 2005.

- Michael Buhlmann: The St. Georgen monastery and the magnus conventus in Constance in 1123 (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 17). St. Georgen 2005.

- Michael Buhlmann: St. Georgen as the reform center of Benedictine monasticism (= sources on the medieval history of St. George , Part VIII = Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 20). St. Georgen 2005.

- Michael Buhlmann: The Benedictine monastery of St. Georgen. History and culture. Two lectures on St. Georgen's monastery history in the Middle Ages and early modern times (= Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 21). St. Georgen 2006.

- Michael Tocha: News from the Benedictine high school in Villingen 1–10. In: Villingen through the ages. Annual issue of the history and homeland association Villingen . Volumes 37-41. 2014-2018.

- Michael Tocha: Basic course in Catholic Enlightenment: Andreas Benedikt Feilmoser, his teachers and the educational world of the Benedictines in Villingen . In: Freiburg Diocesan Archive . Volume 136, 2016, pp. 133–157.

Web links

- The lapidary

- Benedictine Abbey of St. Georgen in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

- The manuscripts of the Sankt Georgen monastery on the website of the Badische Landesbibliothek

Remarks

- ^ Günter Schmitt : Sigmaringen. In: Ders .: Burgenführer Schwäbische Alb. Volume 3: Danube Valley. Hiking and discovering between Sigmaringen and Tuttlingen. Biberacher Verlagsdruckerei, Biberach 1990, ISBN 3-924489-50-5 , pp. 41-62.

- ↑ cf. for example Ulrike Ott-Voigtländer: The St. Georgener recipe. An Alemannic pharmacopoeia of the 14th century from the Karlsruhe Codex St. Georgen 73. Part I: Text and dictionary. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1979 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 17). At the same time medical dissertation in Würzburg; and Matthias Kreienkamp: The St. Georgener recipe. An Alemannic pharmacopoeia of the 14th century from the Karlsruhe Codex St. Georgen 73 , Part II: Commentary (A) and text-critical comparison, Medical Dissertation Würzburg 1992.

Coordinates: 48 ° 7 ′ 37.6 ″ N , 8 ° 21 ′ 15.1 ″ E