Säckingen women's monastery

The Fridolinsstift in Säckingen (lat. Seconiensis ) in today's Waldshut district in Baden-Württemberg , originally a double monastery , was founded in the 6th or 7th century. The monastery was closed again early on. The women's monastery was a royal monastery and its abbess was raised to the rank of imperial prince by King Albrecht I in 1307 . In 1806 the women's monastery was also abolished in the course of secularization .

history

Founding history

The Säckingen monastery was allegedly founded under the protection of the Frankish king Clovis I (466-511) in the 6th century . Stumpf dates the founding year to the year 495, but generally the founding year 522 applies, which is, however, questioned by some historians who assume that the founding was not to the time of Clovis I, but to Clovis II (634-657) going back. According to the current state of research, however, the life of St. Fridolin , who is considered the founder of the monastery, is more likely to be settled in the 6th than in the 7th century, which in turn corresponds to the old traditions.

According to the founding legend, Pope Celestine I sent monks to "Erin" ( Ireland ) in the 5th century to convince people of the Christian faith. The missionary Patrizius founded the Archdiocese of Armagh there in 472 . Fridolin , born around the year 480, is said to have emerged from the monastery school there . From Poitiers in Gaul , he went to the then court of King Clovis I in Orléans in 507 to ask for funds there for the reconstruction of the destroyed monastery and church of Poitiers, which Clovis I finally granted. After this work was done, Fridolin wanted to continue his missionary work in other areas. Clovis assured him of his protection on a renewed visit in 511 and issued him the corresponding letters of safe conduct . From porters he moved to Strasbourg via Metz and the Vosges . His path continued to Chur until he finally discovered the Rhine island near Säckingen around the year 522 and built a church and a missionary site in honor of St. Hilary of Poitiers . On his hike he met the brothers Ursus and Landolphus, who appeared as Fridolin's special benefactors.

Although the founding period at the time of Clovis I is now partially questioned, there are still some indications that the Säckingen monastery could indeed have been founded around this time. After the decisive battles of the Franks against the Alemanni in 496 (Battle of Zülpich) and 506 (Battle of Strasbourg), the Franks needed an outpost to expand their power in the tribal area of the Alamanni. The founding of a monastery on the easily defendable Rhine island near Säckingen was a possible instrument for this.

After the Battle of Strasbourg (506), the Alamanni in the south on the right bank of the Rhine submitted to the protection of the Ostrogoths. Accordingly, Clovis I hardly had the opportunity to dispose of this area or even to make donations in this area. However, after the subjugation and resettlement of the Burgundians, the area on the left bank of the Rhine was within the Franconian sphere of influence from 500 at the latest. Schäfer is of the opinion that a Roman enclave on the right bank of the Rhine had been preserved near Säckingen, which reached in the east as far as the southern Black Forest Alb and in the west as far as the Wehra , which could be taken over by the Franks until they came to power. Accordingly, Säckingen and the Rhine island there belonged to Burgundy on the left bank of the Rhine at that time, which means that the prerequisites for the donation at the time of Clovis I and the foundation of the monastery a few years later were given. Jehle and Englert see a historical core for the early foundation in the support of the Merovingian kingship and their successors, the Carolingians and Ottonians , in which it appears as a monastery owned by the king. There was already a settlement in Säckingen at the time of the Romans, as one can see from the reports of the historian Ammianus Marcellinus. According to his records, the military commander comes Libino was sent against the Alemanni tribe of the Brisgavi, who broke alliances, in 360, who, however, died at the first encounter with the enemy in Säckingen "prope oppidum Sanctio". If one concludes from this that Säckingen is a Roman foundation, parts of the local population could already have been Christianized at the time of the foundation in question. As Schaubinger mentions, Fridolin's gang led through Chur, located in Raetia, the outpost of the Ostrogoth Empire, which shortly after the supposed founding year of 522 passed over the Alamanni to Frankish domination together with the protectorate.

After Brandmüller, the monastery in Säckingen is the oldest monastery in the Alemannia region . Wehling and Weber also confirm this. They date the founding of the Säckingen monastery around the year 600, even before the St. Gallen monastery cell was founded in 612. Clovis II, however, was not born until 634.

6th to 10th century

The monastery was subordinate to the diocese of Constance , whose borders on the right bank of the Rhine extended up to and including Kleinbasel . Ays argues that the Säckingen monastery was subordinate to the Alemanni diocese of Vindonissa ( Windisch ), which would therefore support the founding of the monastery in the 6th century, as this diocese was relocated to Constance before the time of Clovis II. Unfortunately, there are no sources on which he bases his statement. What is certain, however, is that the Säckingen royal monastery had good relations with Poitiers and the Franconian royal court, to which it was directly subordinate and from which it was endowed with ample possessions. At times the Säckingen monastery acted as the royal palace on the Upper Rhine alongside Basel, Zurich and Reichenau monastery .

The Säckingen monastery is said to have received its extensive property in Glarus from the brothers Ursus and Landolphus during Fridolin's lifetime . More recent research dates the acquisition of the Glarnertal by the Säckingen monastery much later. According to this, the Glarnerland should not have come to the Säckingen monastery until the middle of the 8th century . In the 7th century the monastery was involved in the development of the Black Forest . From Hochsal , the Säckingen monastery made settlement advances far into the Black Forest that reached as far as Herrischried . The monastery laid out farms from which the villages of Rippolingen , Harpolingen , Niederhof, Oberhof, Hänner , Binzgen and Rotzel emerged.

The Carolingians tried to get rid of the far autonomous status that the Alemanni enjoyed under the Merovingian kings in the 8th century. At the Cannstatt Blood Court in 746, at the instigation of the Frankish housekeeper Karlmann, almost the entire ruling class of the Alemanni was wiped out. The aim of this action was the complete submission of the Alemanni. Monasteries now became instruments of power for Carolingian rule. In order to avoid expropriation by the Carolingians, many Alemanni now bequeathed their property to a monastery leaning towards them. In return for this, they received their property back in the form of a fief, with which a threatened expropriation could be avoided. The St. Gallen monastery , which initially consisted of a majority of Raetian monks, was increasingly followed by Alemannic aristocratic families in the 8th and 9th centuries. It thus developed into a "refuge" for the Alemannic nobility and their possessions. The Säckingen Abbey, located in the middle of the Alemanni area, developed into a Carolingian bastion, as can easily be seen in the following years from the members of the Franconian nobility. Heilwig, the wife of Welf I and abbess in Chelles , is also said to have been abbess of the Säckingen women's monastery.

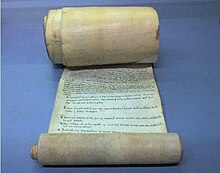

A document dated February 10, 878, in which Charles III. confirms that his sister Bertha , the daughter of Ludwig the German , is the abbess of the Säckingen monastery and that he appoints his wife Richardis as her successor, which is also the first written mention of Säckingen's quod dicitur Seckinga .

The master monastery of the former Säckingen double monastery - there is talk of canons and monks - seems to have been dissolved as early as the 10th century. In the 11th century canons and monks are no longer mentioned. From then on, only chaplains appear who took over the priestly duties for the female inmates. How the management of the monastery association took place can no longer be unequivocally reconstructed due to the lack of documents from this time. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that the overall management of the monastery, similar to the double monastery in Zurich , was under the abbess.

The Säckingen women's monastery was not spared from the invasions of the Hungarians , who ravaged the Duchy of Swabia along Lake Constance and the Upper Rhine by pillaging and murdering in the years 917 and 926 ; it was destroyed and looted.

Otto the Great decided that the island of Ufnau , which belonged to the Säckingen monastery , should be donated to the Einsiedeln monastery . In return, he bequeathed Weesen , Walenstadt and Schaan to the women's monastery in a document dated January 23, 965 , and also granted the monastery full immunity rights . But Beata, the daughter of Rachinbert and Landold's wife, gave the island of Ufnau "Hupinauia" to the St. Gallen monastery on November 19, 741. It is unclear how the Säckingen women's monastery came from there. It is possible that the island came from St. Gallen to the Eberhardinger family and then to the women 's monastery through the abbess Regelinda .

11th to 15th centuries

Tschudi reports in his chronicle that on March 29, 1029 the abbess Berta (Berchta) transferred the office of Meier over the possessions in Glarus to Rudolf von Glarus. He also reports that Rudolf von Glarus called himself "Schudin" (Tschudi) afterwards. This family remained in the possession of the Glarner Meieramt of the monastery for many generations. The feudal lapel, translated into German by Tschudi, ends literally: “… I gave this letter a little insigle / it was given on the 29th day of Merzen / happened in the monastery of Seckingen Anno Domini 1029 in the 12th Zinszal / as Pope John the XX. the Apostolisch Kilch ruled / and Keizer Cunrat richsnet / Warmannus ( Warmann von Dillingen ) Bishop to Costenz and Ernst Translucent Duke in Alemannia what; Trains were so present: Herman von Wessenberg Fryherr / Rudolff von Bilstein, Arnold von Mandach Edelknecht, and Berchtold / the pastor of Louffenberg and others. "

In 1065, Count Arnold von Lenzburg appeared as guardian of the Säckingen monastery and Laufenburg. After the counts of Lenzburg died out in 1072, Emperor Friedrich personally asked the abbess and the chapter women and gentlemen in 1173 to have the umbrella bailiwick over the monastery as well as the associated "Lüt and Land, Glarus, Seckingen Lauffenberg and other Fläcken" on his son To transfer the Count Palatine Otto I of Burgundy , a process "that has never been from old times / then only a Roman Künig or Keizer himself was before Ir Cast-Vogt." Thus, the transfer of the castvogtei to his partisan Arnold von Lenzburg was probably against this right. Tschudi contradicts the statement of Johannes Nauclerus who claims that the umbrella bailiwick of the Säckingen monastery and the cast bailiffs via Zurich and Zürichgau went to Count Albrecht von Habsburg, who was married to the sole heir Ita von Pfullendorf. Only the lower jurisdiction in the villages of Dietikon and Schlieren were transferred to Albrecht at that time. Tschudi also accuses Barbarossa of having many bailiffs over monasteries and places of worship that belonged to the empire and assigned his children to his children.

After Rudolf von Pfullendorf's death, his inheritance was divided between the Habsburgs and the Hohenstaufers. The emperor exchanged what the Habsburgs received for the county in Zurichgau, the castvogtei of Säckingen and for the emperor's estate. The son of Albrecht and Ita's, Rudolf , was able to force that the Säckingen women's monastery was transferred to the Habsburgs as a fief from now on . Rudolf von Habsburg was in dispute over the city of Laufenburg, in which a settlement was reached on September 4, 1207, through the mediation of Arnold von Wart and Baron Konrad von Krenkingen.

In 1254, the Bishop of Basel, Berthold, commissioned the Abbess of Säckingen, Anna von Pfirt, the niece of Count Ulrich von Pfirt , to temporarily take care of Masmünster (Vallis masonis) nunnery, which was oppressed and depressed by malice of the bailiffs and enemies of the church . On December 1, 1260, Anna renounced the monastery’s claims to the forests near Wehr (Baden) donated by Walther von Klingen to the diocese of Constance and the Teutonic Order. Walther von Klingen inherited the rule of Wehr and bequeathed large parts of it to the Klingental Monastery, the Beuggen Order of the Teutonic Order and the Diocese of Constance.

On August 17, 1272, a fire broke out in the house of a baker in Säckingen, which quickly spread across the entire city and reduced everything to rubble and ashes except for the parish church of St. Peter and a few houses. The archive of the monastery also fell victim to the fire, which is why hardly any documents about the monastery have been preserved from before this time. The bones of Saint Fridolin should not have been damaged. Abbess Anna from the Pfirt family decided to entrust this to Eberhard von Habsburg and the son of his late brother Gottfried I, Rudolf III, and not to the Bishop of Basel, with whom Rudolf IV of Habsburg was in feud . It is described that Rudolf brought the coffin with the bones of Fridolin to Laufenburg in order to keep them there until the reconstruction. The canonesses were also housed in Laufenburg until the convent was rebuilt. Rudolf von Habsburg donated an eternal light, which was financed by the "Tullen" - tithe (tillen = boards) of the church in Waldkirch near Waldshut. From the toboggan that Rudolf von Habsburg had built in 1281, it is clear that he also arranged that the income from the Hauenstein customs be used to rebuild the city wall that was destroyed by the fire.

In the year of Rudolf's coronation as king in 1273, he and the abbess of Säckingen Anna von Pfirt wrote a letter to Bishop Eberhard von Konstanz regarding the consecration "post festum" (retrospectively) of the church in Glarus built by the Glarnern . Therein Rudolf acknowledged indirectly that the pen alone is subject to the German Reich and the none other than the German king or emperor Kastvogtei should have, as in times of King " Clodovei Magni had introduced (the Great Clovis) in the year 500". The Habsburgs seem to have appointed a nurse to manage the monastery . In this capacity, a “brother Berchtolden von Henere” (probably Hänner) appears in 1294 in a deed of purchase from a court belonging to the Klingental monastery.

The possessions of the Säckingen Abbey on the Upper Rhine on the right bank of the Rhine ranged from Hauenstein via Schwörstadt to Müllheim (Baden) . The Hollwanger Hof near Riedmatt also belonged to the women's monastery. This farm was probably donated by Walther von Klingen to the Sisters of the Säckingen order, who appeared in 1289 when the knight Ulrich von Rotelstorf handed over his feudal claim to the Hollwanger Hof of the German order commander von Beuggen. "Abbess Anna and the whole convent" thus transferred the fief for 5 Schilling Häller annually to the Teutonic Order Coming Beuggen. It is possible that the Säckingen monastery later transferred the rights to this court to the Cistercian monastery in Olsberg , where in 1296 the abbess Agnesa appears in “in banno et villa Halderwang”. By decree of Duke Albrecht of Austria, the later king, the parish rectors of the parishes Hornussen , Mettau , Murg , Rheinsulz and Zuzgen were instructed to take up residence in Säckingen. This later led to resentment in the local parishes, who felt that they were not represented with sufficient spiritual support.

In Rheinfelden King Albrecht I elevated the abbess von Säckingen to the rank of imperial prince on April 4, 1307 and granted her imperial regalia . In a document from the same year, the abbess of the Säckingen women's monastery is referred to as the princess for the first time. The document begins as follows: "The venerable Mrs. Elisabeth von Bussnang his very dearest princess and Baase ..." Thanks to good management, the number of visitors to the Säckingen monastery was so great at the beginning of the 14th century that the abbess Adelheit von Ulingen decided, with the approval of the chapter, limit the number of canonesses to 25. In order to improve the financial situation of the monastery, the Strasbourg Bishop Berthold von Buchegg arranged that the tithe and the parish divide of Ulm and Renchen should go to the women's monastery .

The joy of the new collegiate church did not last long. Already in 1334 it burned again in Säckingen and the collegiate church fell victim again. The abbess Agnes von Brandis arranged for a new collegiate church to be built, which was not changed by the devastating floods in 1343. The consequence of this flood was the construction of the Gallus Tower , which, with its meter-thick walls, brought the city and the monastery not only military but also security against renewed floods. The new collegiate church, the Fridolinsmünster , was inaugurated in 1360 by Bishop Heinrich von Brandis from Constance. Rudolf IV. Von Habsburg arranged for the Fridolin coffin to be opened in 1356, about which he had a protocol drawn up. He took some relics of the saint for St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna.

Meanwhile the conflict between the Meieramt von Glarus and the Meier Walter von Stadion, who was appointed by the Habsburgs, escalated . In 1352 there was a military conflict, with Walter von Stadion being slain by the Glarnern and the monastery-owned castle in Näfels was completely destroyed. The citizens of Glarus, embittered by the Habsburg rule, now leaned against the strengthening Swiss Confederation. This now led to an open conflict with the Habsburgs, which the Roman Emperor Charles IV , who was summoned to arbitrate, could not change much. Only after Albrecht's death in 1358 did the situation between the two parties to the dispute eased again. Albrecht's successor was his son Rudolf IV , who pursued a less aggressive policy. However, this peaceful policy was destroyed again by the appointed governors Peter von Thorberg and Egloff von Ems. So it happened that in 1386 at the Battle of Sempach Glarus people fought against the Habsburgs. The retaliation attempt of the Habsburgs in 1388 in the battle of Näfels sealed the departure of the Glarus people. Now that they had completely taken over the sovereignty, they also wanted to get rid of their liabilities to the Säckingen women's monastery. For this purpose, a ransom contract was signed between Säckingen and Glarus in 1390. The only exceptions to this were the monastery-owned farm in Glarus with the associated annual interest and the church treasury in Glarus, which, however, were also bought off after further negotiations in 1395. This did not affect the enfeoffment of the tithe, which was actually paid to Zurich until the secularization in 1806. It should be noted that the hostilities of the Glarus initially were not actually directed against the women's monastery, but only against the Habsburgs.

It seems that at that time there were not only disagreements with Glarus subjects, but also with the subjects of the city of Säckingen; this emerges from a compensation settlement dated October 3, 1385 between the city of Säckingen, represented by the mayor and the council, and the abbess Claranna von Hohenklingen. The citizens are said to have broken into the monastery on the orders of the Duke of Austria, broken into the cellar and stolen the wine inside.

In 1379 the women's monastery received the Zoll zu Frick as a gift from Count Sigmund von Thierstein , who was in dispute with the Basel bishop Johannes von Vienna. According to the story, a follower of the bishop, Henmann von Bechburg , is said to have captured Count Sigmund and wanted to hand him over to the bishop. However, he managed to escape and, as he wrote himself, was "saved again by God and St. Fridli". In gratitude for his “salvation” he set up the foundation.

In 1409 Margrave Rudolf III vacated the building . von Hachberg-Sausenberg granted the abbess of the women's monastery, Claranna von der Hohenklingen , the previously disputed right to the lower jurisdiction in the Zwing und Bann Stetten.

A document dated May 3, 1453 by the abbess Agnes von Sulz at the time shows how far the monastery had an influence. In it, at the instigation of Bishop Ruprecht of Strasbourg, it was agreed that the abbess would separate the parish of Ulm from the parish priests Renchen by virtue of her right of patronage .

16th century until the dissolution

During the Reformation, the women's monastery was split into two camps. Some of the nuns tended to the new doctrine of the faith, while the other part stuck to the old doctrine, including the abbess Anna von Falkenstein (1508–1534) at the time. The canonesses Magdalena von Freiberg and Magdalena von Hausen were punished because, even after the abbess insisted, they refused to refuse Lutheran teaching.

The Säckingen women's monastery was not attacked directly during the German Peasants' War . The citizens of the cities of Säckingen and Laufenburg successfully secured the city against the Black Forest group led by Kunz Jehle . Instead, the rebels focused their attention on the nearby Benedictine monastery of St. Blasien, which was totally devastated.

After the death of Abbess Kunigunde von Hohengeroldseck in 1543, the Säckingen monastery only had two canons and three canons. The church reform also left its mark on the Säckingen Abbey. "Spiritual decline" was reported, which led to the fact that from 1548 to 1550 no canoness lived in the Säckingen women's monastery. Emperor Ferdinand I took on this matter personally and ordered the Bishop of Constance Christoph Metzler von Andelberg to restore order to the Säckingen women's monastery. He sent his vicar general to Säckingen to investigate the allegations. It turned out that “people lived, lived and acted quite differently” than the monastery statutes provided for. The abbess had let herself be carried away by the changing times and forgot the "monastic discipline" and got involved with a deacon. The two wanted to get married, but this plan was betrayed and the deacon had to flee. When the abbess followed him, she was held by the citizens. Emperor Ferdinand I thereupon sentenced her to imprisonment in one of the monastery's own buildings, the "Old Court", under the supervision of the monastery administrator and Meier Johann Jakob Freiherr von Schönau . Since the abbess "had let herself be seduced", she had to renounce her dignity. Thereupon Agatha Hegenzer von Wasserstelz was elected abbess from the three remaining canons of the Dominican order, who had been brought in from St. Katharinental Monastery near Diessenhofen . Accustomed to the strict rules of the order, she now, together with Bishop Christoph, introduced the rules of St. Augustine in Säckingen . The women had to take the vows of poverty, obedience and chastity. In addition, they were forbidden to “return to the world”, they were denied all property, and more. These strict rules of the order met with great resistance from the still existing canonesses and so it came about that none of the canonesses volunteered for re-acceptance. Extensive construction work was also carried out under the direction of the new abbess. In addition to some other buildings, this also included the construction of a new abbey house and the basement house in Birkingen , which have been preserved to this day.

In the first years of the Thirty Years War , Säckingen Abbey was hardly affected by the war. However, this changed after the troops of the Swedish king Gustav Adolfs penetrated to the Upper Rhine in 1632. When Freiburg im Breisgau was taken by the Swedes in 1632 , the canonesses fled with the most valuable items to Baden to the Confederates, who promised them protection. In this way they avoided the terrible battles that broke out in the area around Säckingen. After Archduke Ferdinand succeeded in defeating the Swedes in the Battle of Nördlingen on September 6, 1634 , they withdrew from the Upper Rhine area, whereupon the canons returned to Säckingen. Foreign troops came into the country again as early as 1638. Allied with the French, the Swedes now moved under the leadership of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar through the Basel area to the Säckingische Fricktal . The abbess Agnes von Greuth fled just in time to the castle of the barons von Roll in Bernau . On February 3, 1638, the French crossed the Rhine from Fricktal and occupied Säckingen and Laufenburg and besieged Rheinfelden. The monastery then had to accept extensive contributions and billeting . The war dragged on until 1648, so that the abbess stayed in Rapperswil most of the time . She could only return in 1651, as the French did not leave Säckingen until all contributions had been paid.

In 1673 the strict rules of the order were loosened somewhat by the then abbess Maria Cleopha Schenk von Castell and the Constance prince-bishop Franz Johann Vogt von Altensumerau and Prasberg in order to secure the new generation of the monastery. The new rules of the order led to a renewed influx of applicants, so that the Bishop of Constance Johann Franz Schenk von Staufenberg even saw himself compelled in 1719 to tighten the admission criteria ( test of nobility ) for the women, who anyway only came from aristocratic circles. Whereas previously four noble ancestors from each side, i.e. eight in total, were required to gain acceptance in the monastery, eight from each side, i.e. a total of sixteen noble ancestors, were now required.

Shortly after Abbess Maria Cleopha Schenk von Castell took office in 1673, the French King Louis XIV attacked Holland and conquered it, whereupon the German Emperor Leopold I declared war on him. This was not without consequences for the Säckingen women's monastery. Again the area on the Upper Rhine became a theater of war. When the French took Neuenburg am Rhein in 1675 , the women of the monastery fled to Klingnau . When the fortunes of war took a turn, they returned, but had to flee again in 1678 when Marshal François de Créquy besieged the city of Rheinfelden. When Créquy moved further up the Rhine, the canons fled to Böttstein at the last minute on July 6, 1678 . Just one day later, around 6,000 men from the French army arrived in Säckingen. In order to prevent an advance across the Rhine, the Säckingen Rhine Bridge was set on fire by the imperial troops. The French then plundered the town of Säckingen, set it on fire and withdrew to Rheinfelden. The monastery was not looted because some officers had relatives among the canonesses, but the flames also spread to the church and destroyed all the altars there. The monastery building itself was spared from the flames.

The Austrian War of Succession made Säckingen a theater of war again in 1738. Again the most valuable belongings were fled, back to the castle of the Barons von Roll in Bernau. In 1740, Säckingen was forced to billet French troops. When the tide turned again, the French withdrew and in 1748 peace was made.

In 1741 the abbess Maria Josefa Regina von Liebenfels bowed to the pressure of the saltpetre riots in Hauenstein , just like the monastery of St. Blasien a few years earlier . On February 21, she and the Hauenstein unification masters signed the ransom contract from serfdom for a sum of 11,500 guilders.

In 1751, the organ builder's carelessness caused a fire in the collegiate church, which quickly spread to the nave and the towers. Only the choir was spared from the flames.

Abolition of the monastery

As early as August 8, 1785, the Austrian government in Freiburg attempted to dissolve the Säckingen women's monastery. The ladies were ordered by imperial order to go to the Freiweltlich aristocratic women's monastery in Prague , founded by Empress Maria Theresia in 1755 . The abbess Marianna Franziska von Hornstein then went to the court in Vienna in September 1785 to lodge the sharpest protest against the decision to dissolve. In an audience with Emperor Joseph II , she managed to reverse the abolition of the monastery. On January 12, 1786 the monastery received a new imperial letter of protection. The French Revolution and the coalition wars connected with it brought another turning point in the history of the monastery. The monastery lost its financial basis due to the consequences of billeting, looting and, last but not least, the agreements concluded in the Peace of Lunéville - including the cession of the Fricktal and the Breisgau. In 1806, like many other monasteries, it was abolished by secularization .

List of Abbesses

The head of the convent was the abbess (derived from abbot, late Latin: abbas, from Hebrew: abba father). She was responsible for both the pastoral and secular direction of the monastery.

| Surname | First name (s) | Born | Died | Term of office | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| of Saxony | Heilwig | at 778 | after 833 | 826 | Heilwig was Count Isenbart's daughter. She was the wife of Welf I and abbess in Chelles . Their son Konrad I was Count im Albgau , their daughter Judith, the wife of Ludwig the Pious and another daughter of hers, Hemma was married to Ludwig the German . |

| Bertha | before 839 | March 26, 877 | to 877 | Daughter of Ludwig the German and Hemma von Altdorf , sister of Karl III. , Hildegard , Karlmann, Ludwig III. the younger, Irmgard von Chiemsee and Gisela (wife of Berthold I of Swabia). She was a great-granddaughter of Emperor Charlemagne . Richardis her successor, was her sister-in-law. | |

| Richardis | around 840 | September 18, 893 | 877-893 | Daughter of Erchanger , Count of Nordgau, and wife of Karl III. Berthold I. von Schwaben was her brother. | |

| Kunigunda | 893– | possibly the daughter of Berchthold I of Swabia. She died on February 7th, probably in the year 915. | |||

| Regelinda | 958 | probably after 949 to 958 | Grandmother of Adelheid , wife of Otto the Great and wife of Burchard II (Swabia) | ||

| from Swabia | Berta ? (presumably) | 931 | Jan. 2, 966 | possibly up to 966 | Berta , wife of Rudolf of Burgundy , daughter of Burchard II (Swabia) . Not documented as Abbess of Säckingen ! |

| of Burgundy | Adelheid ? (presumably) | 931 | 999 | possibly up to 999 | Adelheid , wife of Otto the Great , daughter of King Rudolf II of Hochburgund appears in a document from 965 as an intervener in an exchange of goods between the monasteries of St. Gallen and Säckingen. Not documented as Abbess of Säckingen ! |

| Bertha | 1029 | Glarus feudal contract from the year 1029 names Bertha (Berchta) as Abbess of Säckingen | |||

| Elisabeth (Elßbeten) | 1220 | A dispute between the Glarner Meier Heinrich Tschudi and the monastery in 1220 names a certain Elßbeten as abbess of Säckingen | |||

| from Pfirt | Anna I. | approx. 1256 - after Dec. 1, 1276 | An abbess Anna is mentioned in a document in 1256 when Diethelm von Windegg was granted the Meyeramt zu Glarus. Anna was an abbess at the time of the fire in 1272. Anna must have been there at least until December 1st, 1276, as evidenced by a document from this date in which an Erkenfrid, the singer from Basel and the nurse of the hospital in Säckingen, wrote: “ ... that I advise and for the sake of Annen der ebtischen von Sekkingen and as irs capitels and öch the hospital brothers ... " | ||

| from Wessenberg | Anna II | 1306 | approx. 1285-1306 | An abbess named Anna, who is very likely Anna von Wessenberg, is mentioned regarding the inheritance of the Rhine sulz in 1285. Another document issued by Abbess Anna von Wessenberg is dated August 12, 1291. | |

| from Bussnang | Elisabeth | June 13, 1318 | 1306-1318 | After the murder of Albrecht von Habsburg in 1308, agreed to Hartman von Windegg's sale of the Meieramt in Glarus to Leopold and Friedrich von Habsburg. | |

| from Ulingen | Nobility | 1318-1330 | |||

| from Brandis | Agnes | 1330-1349 | Was appointed abbess on November 27, 1330 by Bishop Rudolf von Konstanz. Initiated the rebuilding of the monastery church after the fire of 1334. Consecration in 1360 by the Bishop of Constance Heinrich von Brandis. | ||

| from Grünenberg | Margaretha | around 1355-1380 | Appears on August 1, 1356 as Abbess von Säckingen in a document from Wilhelm von Hauenstein . Likewise 1360; and 1367. | ||

| from the Hohenklingen | Claranna | 1422 | 1380-1422 | On October 3, 1385, he concludes a contract with the city of Säckingen regarding compensation. In 1409 Margrave Rudolf III vacated the building . von Hachberg-Sausenberg the abbess the previously disputed right to the lower jurisdiction in the Zwing und Bann Stetten . ; Fiefdom from 1414 | |

| from Bussnang | Margareth | 1422 | 1422-1422 | Died within a month | |

| from the Hohenklingen | Johanna | 1431 | 1422-1428 | ||

| of blades | Margaretha | 1431 | 1428-1430 | ||

| from Geroldsegg | Anastasia | 1432 | 1430-1432 | ||

| from Sulz | Agnes | 1409 | 1484 | 1432-1484 | Loan contract from 1454 |

| from Falkenstein | Elisabeth | 1508 | 1484-1508 | Letter of protection from 1495, letter of grace from 1495 and 1500 from Emperor Maximilian I. | |

| from Falkenstein | Anna | April 24, 1534 | 1508-1534 | Treaty of 1508 (daughter of Thomas von Falkenstein and Ursula von Ramstein and sister of Elisabeth, the former abbess) | |

| from Hohengeroldseck | Kunigunde | 1534-1543 | Award of the Meieramt to Hans Jakob von Schönau , 1537 | ||

| von Hausen | Magdalena | 1551 | 1543-1548 | Letter from 1544, mentions 1543 | |

| Hegenzer von Wasserstelz | Agatha | March 21, 1571 | 1550-1571 | Johann Melchior Heggenzer von Wasserstelz was forest bailiff of the county of Hauenstein from 1537 to 1559 . Writing from 1560 and 1569 | |

| from Sulzbach | Maria Jacobea | 1600 | 1571-1600 | Founded the large window "on the right Seyten" with their coat of arms in the parish church in Waldkirch. | |

| Giel from Gielsberg | Ursula | 1600 | 1600-1614 | Writing from 1601 | |

| Brum of Herblings | Maria | 1614-1621 | Writing from 1618 | ||

| from Greuth | Agnes | 1658 | 1621-1658 | Writing from 1623 and 1653 | |

| from Schauenburg | Franziska | 1588 | 1672 | 1658-1672 | Letter from 1658, legal trade from 1667 |

| Gift from Castell | Maria Cleopha | 1672-1693 | Introduced new rules of the order in 1673. Writing from 1677 | ||

| from Ostein | Maria Regina | 1643 | 1718 | 1693-1718 | Letter from 1701 Completed the expansion of the minster in 1703. |

| from Liebenfels | Maria Barbara | 1738 | 1718-1730 | ||

| from Hallwyl | Mary Magdalene | 1730-1734 | |||

| from Liebenfels | Maria Josefa Regina | 1734-1753 | called 1741; in the first year (1734) she had to flee from the French with the relics. She had the cathedral decorated. | ||

| from Roggenbach | Helena | 1734 | 1753-1755 | ||

| from Hornstein-Göffingen | Marianna Franziska | July 2, 1723 | December 27, 1809 | 1755-1806 | Last abbess of the Säckingen monastery |

Secular offices of the monastery

Patrons / patrons

Originally it was the king's task to ensure protection for the country and its inhabitants; This was all the more true for the Säckingen monastery as it was directly imperial. This status of imperial immediacy was withdrawn from the monastery by King Friedrich I (Barbarossa) by transferring the guardianship to his partisan Ulrich von Lenzburg and, after his death in 1173, campaigned for the cast or guardianship to his son Otto I. ( Burgundy) was transferred. With this, the Säckingen monastery actually lost its imperial immediacy because sovereign princes now exercised the umbrella bailiff, which was similar to an imperial fief , and later even a Habsburg fief . From 1181 until the secularization in 1806, the Habsburgs held the umbrella bailiwick.

These protectors or patrons, as they were later called, originally only received a share of the fines and fines imposed to finance their expenses (military protection and exercise of jurisdiction), but in the following years they appropriated the taxes that were paid to the Reich and its members Above all, they were entitled to and also imposed further taxes for the individual places and residents. Not only in Säckingen and not only the monasteries lost a considerable part of their income and possessions.

For the early Habsburgs, control over the market towns of Säckingen and Laufenburg meant the acquisition of two bridgeheads on the right bank of the Rhine and thus the first step in their territorial bridging, which was carried out until the middle of the 13th century, from their home countries in Aargau to the southern Black Forest (around 1235 they also acquired the Bailiwick of the Imperial Monastery of St. Blasien ) to the Upper Rhine Plain and from there to Upper Alsace , where their second large property complex was located. For the purpose of military security, with the consent of the monastery, they built fortifications on its territory, such as Hauenstein Castle , and occupied them with ministerials .

List of umbrella bailiffs (after Friedrich I. )

The following umbrella bailiffs are known for the Säckingen monastery :

- Friedrich I (Barbarossa) as German King

- Ulrich von Lenzburg , known from documents, 1063 to 1172

- Otto I (Burgundy) , 1173 to 1181 (according to Schulte, the bailiwick went to Albrecht von Habsburg at this time, with the exception of the Sackingian bailiwick of Glarus)

- Albrecht von Habsburg , 1181 to 1199

- Rudolf II (Habsburg) , 1199 to 1232

- Albrecht von Habsburg , 1232 to 1239

- Rudolf IV of Habsburg , 1240 to 1288 (founder of the Habsburg-Laufenburg line)

- Albrecht and Rudolf von Habsburg , 1288 to 1290

- Albrecht von Habsburg , 1288 to 1308

- Friedrich and Leopold von Habsburg , 1308 to 1326 respectively. 1328

- The Meieramt Glarus was delegated to Count Friedrich von Toggenburg

- Albrecht and Otto von Habsburg , 1328 to 1339 respectively. 1358

- The Meieramt Glarus was delegated to Herman von Landenberg in 1329, followed by Eberhard von Landenberg, Johann von Hallwyl, Ludwig von Rottenstein, Ludwig von Stadion and then his son Walter von Stadion.

- Rudolf IV of Habsburg , 1358 to 1365

- The Meieramt Glarus was awarded in 1362 by Bishop Rudolf von Gurk to Peter von Thorberg and from 1367 to Knight Egloff von Ems

- Leopold of Austria , 1365 to 1386

- Friedrich of Austria , 1386 to 1439

- Albrecht VI. (Austria)

- Sigismund of Austria

- Maximilian of Austria , 1495 to 1519

- Charles V , 1520 to 1558

- Rudolf II , 1582 to 1612

- Maximilian III (Upper Austria) , 1613 to 1618

- Leopold V (Austria-Tyrol) 1627, until 1632

- Ferdinand III. , 1652 to

- Sigismund Franz (Austria-Tyrol)

- Emperor Leopold I , 1666 to 1705

- Emperor Joseph I , 1708 to

- Emperor Charles VI.

- Empress Maria Theresia , 1742 to 1780

- Emperor Joseph II , 1786 to

Meier of the pen

The possessions of the women's monastery in Säckingen were widely scattered. In order to be able to manage these remote properties better, the monastery employed local administrators, so-called Meier . The Meier exercised lower jurisdiction in the name of the monastery. This office was partially transferred to life or as a hereditary fief. Meier for the possessions in Glarus provided the Tschudi family for many generations. The Tschudi were briefly followed by the von Windek family (1253–1288), until they finally fell to the Habsburgs as well. The Meieramt in Säckingen was divided into a large and a small Meieramt. The Lords of Stein and after them the Lords of Schönau the Great and the Lords of Wieladingen the Small Meieramt as hereditary fiefdoms. The extent of the small Meieramt can be seen from a feudal lapel from 1333 by the nobleman Ulrich von Wieladingen. Accordingly, the Dinghöfe Hornussen , Murg , Oberhof , Herrischried , Stein and Schliengen belonged to the small Meieramt . A certificate dated November 30, 1306 gives a little insight into the genealogy of the Wieladinger family. The sons of the late Ulrich von Wieladingen , "Hartman von Wieladingen torherre ze Sekingen, Vlrich and Rudolf, brothers, hern Vlrichs blessed süne von Wieladingen, knight" sold a wine cellar in Schliengen back to the monastery. The Kleine Meieramt bought the pen back in 1373 from Hartman von Wieladingen for 875 gold guilders.

Voice attendant

The position and activity of a spykeeper, spicularius seconiensis , roughly corresponded to the activity of a central administrator to whom the farms' income was delivered. In 1240 a Konrad and in 1301 an Ulrich are mentioned in this position. This Ulrich probably comes from the von Hauenstein family , because Johann von Hauenstein, who was married to Anna von Buttink, then held the office of warehouse attendant as a fief. Although this was a very lucrative office, he gave it up again in 1311 and retired to his castle and contented himself with the rest of his feudal and interest income.

The monastery buildings

The entire island of Säckingen was originally a monastery area. Until then, two bridges connected the suburb with the Rhine island. The Säckinger Rheininsel was built on in the northern part; the southern part, the "Au", was used for agriculture. The built-up part with its triangular, only a few hundred meters long floor plan was mainly covered by the monastery facilities. In the center, today's Münsterplatz, was the large “Seelhof”, the Carolingian royal palace . The few streets of the small settlement ran next to it. The market was in the southern Steinbrückstrasse, which was called Marktgasse until the 19th century. The dominant building on the island was the Fridolinsmünster , whose Romanesque church building with its 60 meters length around 1000 AD may have been one of the largest structures in the area. Little by little, more people settled on the monastery island, so that little by little the town of Säckingen developed from it. After the right arm of the Rhine was filled in in 1830, it is difficult to imagine today what the former monastery island looked like and which buildings once belonged to the monastery. Many of the former monastery buildings were destroyed in the town fire in 1678.

The originally built-up part of the island in the 14th century ran from the Gallusturm in the east along today's Rheinbadstraße to the west. The right row of houses seen from the Gallus Tower formed the end of the right arm of the Rhine. The city gate was at the intersection of Rheinbadstrasse and Steinbrückstrasse. As the name suggests, the right-hand bridge ran north at the site of today's Steinbrückstrasse. From the city gate, following today's Schützenstraße, the left row of houses formed the end of the city up to the Scheffelstraße intersection. The city limits ran along Scheffelstrasse in a southerly direction to the extension across today's park to the Thief Tower. The western part of today's Scheffelstrasse formed the so-called Au, which at that time was only used for agriculture.

The collegiate church

The Fridolinsmünster is a Gothic monastery church originally built in the Romanesque style and rebuilt in the 14th century under the abbess Agnes von Brandis after a fire. In the 16th century, the abbess Maria Jakobea von Sulzbach arranged for the two church towers to be rebuilt. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the cathedral was renovated with elements of the baroque . The oldest surviving part of the church is the crypt . The expert opinions on dating differ widely. Some experts date them to around the 8th / 9th centuries, others to the 10th / 11th centuries. For more information on the Fridolinsmünster see main article Fridolinsmünster .

The St. Gallus Chapel

The St. Gallus Chapel was also located on the monastery island of Säckingen. The Gallus Chapel, whose name is reminiscent of the St. Gallen monastery where monk Balthasar, the author of the Vita of St. Fridolin, attended the monastery school there, probably dates from the 10th century. It has been preserved to this day and has been converted into a residential building.

Residential houses

In addition to the collegiate church, numerous other buildings belonged to the monastery. During the reconstruction after the fire of 1272, a separate house with a household was supposed to have been built for each canon. Klemens Schaubinger speaks of 40 such houses.

The old courtyard

In the 14th century, the abbess of the time, Elisabeth von Bussnang, extended the monastery complex from the Carolingian era to include the “Old Court”, which was rebuilt in the 16th century and is still there today.

Abbey building

The abbey building, built in the late Gothic style between 1565 and 1575 by the abbess Agathe Hegenzer von Wasserstelz and her successor Maria Jakobea von Sulzbach, stands opposite today's town hall. It is a box building with two stepped gables. The family coats of arms of the two builders are attached to the entrance portal.

The Schönau Castle

The Schönau Palace in its current form was not built by the Säckingen monastery, but by the barons of Schönau. In 1500 they acquired a noble residence from the 13th century from the monastery that was located at this point and converted it into a city palace.

Gallus Tower

As a result of the floods of 1343, the monastery had the Gallus Tower built in the east of the Rhine Island. This tower was part of the city fortifications and offered the monastery island military protection as well as security against a renewed flood, as this protected the island like a breakwater. This was followed by the city wall on two sides of which remains are still visible. The masonry of the Gallus Tower is made of irregular stones that used to be plastered. So-called boss cubes with seams were used for the window sills, drapery and arched lintels. The round tower is covered with a polygonal tent roof.

Theft

The now heavily modified in appearance, in the 19th century by Theodor Bally as a water tower converted Diebsturm was at the western end of the former monastery as the Gallusturm at the east end, part of the fortification. The tower originally dates from Roman times.

Former possessions

During the Carolingian and Merovingian times, the women's monastery was given large estates. The monastery had the largest real estate on the left bank of the Rhine in the area of today's Switzerland, in the Fricktal and other possessions up to Glarus and Solothurn. In addition, the abbess had the right of patronage in 29 parishes. His rulership on the right bank of the Rhine stretched from the mouth of the Alb near Albbruck down the Rhine to Schwörstadt , Schliengen and Müllheim (Baden) .

Cities / Dominions

- Glarus

- Ufenau Island in Lake Zurich and the surrounding towns (was donated to Einsiedeln Abbey in the 10th century )

- Schaan (was donated to the Säckingen Abbey in 965 by Otto the Great as a compensation for the renunciation of the island of Ufenau)

- Weesen (with customs and shipping on the Walensee)

- Walenstadt

- Bad Säckingen

- miles

- Hornussen AG

- Laufenburg (Baden)

- Laufenburg AG

- Untersiggenthal (9th to 11th century)

Parish churches / parishes

- High salute

- Görwihl

- Obersäckingen

- Glarus

- Mettau

- Großlaufenburg

- To close

- Stale

- Kaisten

- Sulz AG

- Hellikon (parish of the community to Wegenstetten)

- Reiselfingen

- Murg

- Hornussen

- Rheinsulz

- Waldkirch

Castles

- Altenstein Castle (presumed)

- Hauenstein Castle (presumed)

- Laufenburg Castle

- Ofteringen Castle - Laufenburg

- Näfels Castle , today the Franciscan monastery of Mariaburg stands here

- Rheinsberg Castle

- Wieladingen Castle

Dinghies and courts

County of Hauenstein

- Murg , included the lower court in the villages of Murg, Harpolingen, Rhina, Diegeringen, Niederhof, Egg, Katzenmoos (?), Wiele (?), Obersäckingen and Dumus (?)

- Murg Oberhof , included the lower court in the towns of Oberhof, Zechenwihl and Thimos

- Herrischried , included the lower court in the villages of Herrischried, Herrischwand and Schellenberg (?)

County of Laufenburg

Reign of Rheinfelden

Other property

The women's monastery had its own farms and property in the following localities:

- Auggen (feudal estates)

- Atzenbach (feudal estates)

- Bellingen (feudal estates)

- Kellerhof in Birkingen

- Böttstein (ground interest)

- Bözen (tithe right)

- Buus (tithe right)

- Dottikon - Hereditary interest for the tithe that the Königsfelden monastery had to pay to Säckingen.

- Elfingen

- Etzgen (formerly Eczken, Etkon, Eitkon, Etken [1351], Etzkon [1428]) - two mills and a farm

- Etzwil (land interest)

- Farnsburg , lordship (land interest)

- Freienwil (goods)

- Freudenau - Ferry rates at Freudenau ( Untersiggenthal )

- Frick - Customs

- Galten (near Gansingen ) had a farm

- Hendschiken - inheritance interest for the tithe that the Königsfelden monastery had to pay to Säckingen.

- Hellikon (mill)

- Hollwanger Hof near Riedmatt ( Karsau )

- Hornussen (Kellerhof)

- Hottwil (courtyards)

- Ittenthal

- Leidikon (mill)

- Kutz (feudal estates)

- Leuggern (interest payments)

- Liel (Schliengen) (feudal estates)

- Maiden (tithe right)

- Mandach (lower jurisdiction)

- Mauchen-Schliengen (feudal estates)

- Müllheim (Baden) (feudal estates)

- Niedereggenen - Schliengen (feudal estates)

- Niederhofen (feudal estates)

- Niederzeihen (Vogtei)

- Obereggenen-Schliengen (feudal estates)

- Oberfrick

- Othmarsingen - inheritance interest for the tithe that the Königsfelden monastery had to pay to Säckingen.

- Reiselfingen ( Kehlhof )

- Rietheim (Erblehenshof)

- Schinznach (feudal estates)

- Schliengen - The "Freihof" with jurisdiction and vineyards. It should be mentioned here that there were a total of three courts of justice in Schliengen. In addition to a dinghof belonging to the bishopric of Basel, the Murbach monastery also had a court, which came to the Schnewlin family in the middle of the 13th century . These in turn exchanged it for other goods with the Johanniterkommende in Freiburg at the end of the 13th century. In 1319 the Johanniter sold the Schliengen farm, with the exception of the church treasure, to the newly founded Königsfelden monastery .

- Schupfart (tithe and interest goods)

- Sitzenkirch (feudal estate)

- Stein (Wirtshaus zum Löwen)

- Stetten near Lörrach - compulsion and ban

- Unteralpfen (mill)

- Unter Schwörstadt - The church, a salmon scales ( fishing gallows ), ground interest, front meadows and forest

- Villnachern (interest)

- Wegenstetten (tenth)

- Weir (Baden) (forest)

- Wil AG ob Mettnau, (St. Wendelin Chapel)

- Wittnau AG

- Wölflinswil

- Zeiningen (Hofgüter)

- Zell im Wiesental - The fiefdom of Zell was given to the Lords of Schönau by the Säckingen monastery , but it still moved in a few tithes and retained the ownership of the older Fronmühle. In addition, there were three other mills that the Säckingen monastery lent as a man's loan and received annual interest for them. This also included the village of Atzenbach .

- Zuzgen (tenth)

Fishing rights

Until its dissolution, the monastery had fishing rights on the Rhine "between the two Rhine bridges Säckingen and Laufenburg". This emerges from the state treaty between the Grand Duchy of Baden and the Swiss canton of Aargau from the 17th autumn month of 1808.

literature

- Klemens Schaubinger: History of the Säckingen Abbey and its founder, St. Fridolin. in the Google book search Einsiedeln 1852

- Friedrich Wilhelm Geier: The land ownership of the Säckingen monastery in the late Middle Ages. Heidelberg 1931.

- Hugo Ott, Bernhard Oeschger, Judith Wörner, Hans Jakob Wörner: Säckingen: the history of the city. Theiss, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-8062-0191-9 .

- Rudolf Metz: Geological regional studies of the Hotzenwald. 1980, ISBN 3-7946-0174-2 .

- Johann Friedrich : Church history of Germany: The Merovingerzeit. Bamberg 1869, p. 411f. online in Google Book Search

- Walter Berschin (ed.): Early culture in Säckingen. Ten studies on literature, art and history. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen 1991, ISBN 3-7995-4150-0 .

- Fridolin Jehle, Adelheid Enderle-Jehle: The history of the Säckingen monastery. Sauerländer, Aarau 1993, ISBN 3-7941-3690-X . (Contributions to the history of Aargau, Vol. 4) doi: 10.5169 / seals-110013

- Mechthild Pörnbacher: Vita Sancti Fridolini. Life and miracles of St. Fridolin von Säckingen. Text-translation-comment. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen 1997, ISBN 3-7995-4250-7 .

- Felicia Schmaedecke, Suse Baeriswyl: The minster Sankt Fridolin in Säckingen: archeology and building history up to the 17th century. Theiss, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1454-9

- Markus Wolter: The newly found, so far oldest land register of the women's choir in Säckingen. Annotated edition. In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. Volume 155. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, pp. 121-213; Text edition and index overtaken by the corrected reprint in: Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins. Volume 156. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 591-665. Revised version also as FreiDok publication by the University of Freiburg im Breisgau, 2011.

- Aloys Schulte: Gilg Tschudi Glarus and Säckingen in the year book for Swiss history , vol. 18, 1893

- Markus Schäfer: The early history of Hauenstein Castle , editor of the Hochrhein History Association, yearbook 2011

- Andre Gutmann: Under the coat of arms of Fidel. The Lords of Wieladingen and the Lords of the Stone between ministerialism and aristocratic rule. Verlag Karl Alber, Freiburg, Munich, 2011, ISBN 978-3-495-49955-9 ( full text as PDF )

- Otto Bally: The women's pen in Säckingen . In: Franz August Stocker (Ed.): From the Jura to the Black Forest , first volume. Aarau 1884, pp. 119–147 and 161–167 archive.org

- Josef Bader : Säckingen's fate described in brief . In: Badenia or the Baden region and people. Journal of the Association for Badische Ortbeschreibung. Published by Josef Bader. First volume, Heidelberg 1864, pp. 202–222 online in the Google book search

- Franz Xaver Kraus : Säckingen . In: The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden. Volume III: Waldshut district. Freiburg i. Br. 1892, pp. 45-61. (online at: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de )

Novels

- Hans Blum : The abbess of Säckingen. Roman from the Reformation period . Jena 1887, 2 volumes excerpts in archive.org

Fonts

- Monk Balther: Fridolinsvita , 10th century

Web links

- Sights in Bad Säckingen

- Säckingen women's monastery in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

- Discover the entry on regional studies online - leobw

Individual evidence

- ^ R. Metz: Geological regional studies of the Hotzenwald. P. 945.

- ↑ Johannes Stumpf: Schweytzer Chronick .

- ↑ Bernhard Oeschger: History of the monastery and the city of Säckingen , p. 20

- ^ Johann Friedrich: Church history of Germany: The Merovingian time , p. 418

- ↑ Markus Schäfer: The early history of Hauenstein Castle , editor of the Hochrhein History Association, yearbook 2011

- ↑ Klemens Schaubinger: History of the Säckingen Abbey and its founder, St. Fridolin, 1852

- ↑ Markus Schäfer: The early history of Hauenstein Castle . Hochrhein History Association (ed.), 2011 yearbook

- ↑ Fridolin Jehle, Anton Englert: History of the Dogern Community , 1978, p. 23

- ↑ Ammian Marcel XXI. c. 2.

- ↑ Julius Cramer: The history of the Alemanni as a Gau story . Scientia, 1971, ISBN 978-3-511-04057-4

- ^ Franz Joseph Mone: Urgeschichte des Badischen Land , vol. I, p. 310

- ^ Johann Friedrich: Church history of Germany: The Merovingerzeit . P. 415, note 1349

- ^ Walter Brandmüller: Handbook of Bavarian Church History: From the Beginnings to the Threshold of Modern Times. I. Church, State and Society. ; II. Church life. EOS Verlag, 1999.

- ^ Hans-Georg Wehling, Reinhold Weber: History of Baden-Württemberg. 2007.

- ↑ Hermann Ays: St. Fridolin and his time. Books on Demand, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8391-8019-8

- ^ Bernhard Oeschger: History of the monastery and the city of Säckingen . P. 25

- ↑ Helmut Maurer: The Bishops of Constance from the end of the 6th century to 1206. P. 21.

- ^ R. Metz: Geologische Landeskunde des Hotzenwalds , p. 945

- ^ Philippe-André Grandidier: Histoire de l´eglise et des évêques-princes de Strasbourg . Levrault, Strasbourg 1778. Vol. 2, Appendix, pp. CCLXVI f. Online at Google Books (in the PDF document p. 600 f.)

- ↑ Klemens Schaubinger: History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin . Verlag K. and N. Benziger, Einsiedeln 1852. pp. 30, 33. Online at Google Books

- ^ Bernhard Oeschger: History of the monastery and the city of Säckingen , p. 23

- ↑ Ekkehart Balther: The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden. P. 906. and: Maximilian Georg Kellner: The Hungarian incursions in the picture of the sources up to 1150: from the gens detestanda to the gens ad fidem Christi conversa (= Studia Hungarica. Vol. 46). Munich 1997. Like Basel , Säckingen was probably destroyed in 917.

- ^ Document book of the Abbey of Sanct Gallen. Part I, year 700-840, p. 7.

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum .

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi : Chronicon Helveticum . Volume I.

- ↑ ZGORh , Vol. 1, p. 71.

- ^ K. Hauser: The barons of Wart. P. 9.

- ^ Regesta Imperii Regeste No. 8772.

- ↑ ZGORh. Vol. 28, p. 92

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 53.

- ^ Pfandrode printed in: Der Geschichtsfreund. Vol. 5, 1848.

- ↑ Basler Urkundenbuch, Vol. 3., Certificate No. 163 of March 28, 1294

- ↑ ZGORh . Vol. 28, Document 81 and 82.

- ↑ ZGORh. Vol. 28, Document 93.

- ↑ Birkenmeyer: Badische Mitteilungen, p. M23

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin.

- ↑ Birkenmayer: Archives from places in the district of Säckingen - communication from the Baden historical commission, vol. 14, p. M77

- ↑ Codex Diplomaticus Alemanniae Et Burgundiae Trans-luranae Intra Fines Dioecesis Constantientis. Volume 2, Trudpert Neugart, p. 467ff.

- ↑ s. Klemens Schaubinger: History of the Säckingen Abbey and its founder, St. Fridolin . Einsiedeln 1852, pp. 109–110 online in the Google book search ; see also: Regesta of the Margraves of Baden and Hachberg 1050–1515 , published by the Baden Historical Commission, edited by Richard Fester , Innsbruck 1892, document number h913 from June 29, 1409; S. h95 online

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 5 NF, p. M21

- ↑ GLA Karlsruhe, inventory 97, 542 - archive link

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 105.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 123.

- ↑ Heidi Leuppi: The Liber ordinarius of Konrad von Mure. University Press Freiburg Switzerland, 1995, p. 66.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 32.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 33.

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum. Volume 1, p. 11.

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum. P. 118.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 54.

- ^ Hefele: Freiburger Urkundenbuch, Vol. 1, Certificate 300

- ↑ ZGORh. Vol. 28 document 82

- ↑ Aarau, Aargauisches Staatsarchiv, Urk. Böttstein No. 7; Edited in: B. Kirschstein, U. Schulze, Corpus of the old German original documents up to the year 1300. Volume V, Berlin 1986, p. 361, N 503.

- ^ S. Höhr: Yearbook for Swiss History. Vol. 43-44, p. 49.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 65.

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum. Volume I., p. 244.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P.56.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 55.

- ↑ ZGORh. Vol. 7, p. 439

- ↑ ZGORh. Vol. 15, p. 478

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 172.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M14

- ↑ s. Klemens Schaubinger: History of the Säckingen Abbey and its founder, St. Fridolin . Einsiedeln 1852, pp. 109–110 online in the Google book search ; see also: Regesta of the Margraves of Baden and Hachberg 1050–1515 , published by the Baden Historical Commission, edited by Richard Fester , Innsbruck 1892, document number h913 from June 29, 1409; S. h95 online

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M14

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 102.

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 100.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M14

- ↑ Bernhard Theil: The (free worldly) women's monastery Buchau am Federsee. P. 251.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M14

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M14

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ^ Günter Esser: Josepha Dominica von Rottenberg (1676–1738): her life and spiritual work. P. 55.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ^ Jabob Ebner: History of the localities of the parish Waldkirch. P. 54.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ^ Notices from the Baden Historical Commission. Waldshut City Archives Document No. 149

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 106.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 18 NF, p. M15

- ↑ Emil Jegge, The history of the Fricktal to 1803, p. 176

- ↑ Emil Jegge, The history of the Fricktal to 1803, p. 176

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum.

- ↑ Communications from the Institute for Austrian Historical Research, Volumes 7 and 8, Aloys Schulte: Studies on the oldest and older history of the Habsburgs and their possessions, especially in Alsace . Studies II. And III.

- ↑ Tschudi Chronik Volume 1, p. 270 printed in the history of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin.

- ↑ ZGORh, Vol. 15, p. 466

- ↑ ZGORh. Vol. 15, p. 240

- ^ Sources on Swiss history. Vol. 15.1. Teil, Basel, 1899, p. 125.

- ^ Blumer: Glarner Urkundenbuch. I, 33

- ↑ Mone: ZGORh, Vol. 24, p. 163

- ^ History of the Säckingen monastery and its founder, St. Fridolin. P. 55.

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ Jakob Ebner: History of the localities of the parish Waldkirch, 1933

- ↑ Markus Schäfer: The early history of Hauenstein Castle . Hochrhein History Association (ed.), 2011 yearbook

- ^ Theodor von Liebenau: History of the Königsfelden monastery. P. 48

- ^ R. Oldenbourg: Journal for name research. Volume 15-16, p. 92 and ZGORh. Vol. 6, p. 105

- ^ Theodor von Liebenau: History of the Königsfelden monastery. P. 48.

- ^ Theodor von Liebenau: History of the Königsfelden monastery. P. 48.

- ^ Theodor von Liebenau: History of the Königsfelden monastery. P. 48.

- ↑ Georg Tumbülle: On the history of the former patronage parish of Reiselfingen in Säckingen . In: ZGORh , 72, 1918, p. 114

- ↑ On the late medieval Säckinger Dinghofverband Schliengen see: Markus Wolter: The newly found, so far oldest land register of the Säckingen choir . Annotated edition . In: Journal for the History of the Upper Rhine , Volume 155, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer 2007, pp. 121–213; Text edition and index overtaken by the corrected reprint in: Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins , Volume 156, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 591–665, entry with images in the Marburg Repertory

- ^ Certificate of June 10, 1258 ZGORh. Vol. 28, p. 92

- ^ Repertory of the farewells of the federal diets: from 1803 to the end of 1813. Volume 2, pp. 187ff.

Coordinates: 47 ° 33 '10.4 " N , 7 ° 56' 58.3" E