Pauline monastery Bonndorf

The Paulinerkloster Bonndorf was a Pauline monastery in Bonndorf in the Black Forest in the district of Waldshut in Baden-Württemberg .

history

Beginnings

The donor's letter , only preserved in copies, dates from October 30, 1402. Baron Rudolf von Wolfurt and his wife Elisabeth von Krenkingen donated the church of St. Peter and Paul including the associated patronage rights with the consent of their son Wolf, the mayor and council and the parish church . In return, the order undertook to pastorate the parish, read an annual mass for the donors and schirmer and take on the usual burdens. The donors received their graves in the church.

On December 22nd, 1402, Marquard von Randegg, as Bishop of Constance in association with the cathedral chapter, confirmed the conversion of the secular parish church into a monastery church and increased the foundation by renouncing his shares in the income of the Bonndorfer parish. At the Council of Constance, Pope Martin V issued around 14 bulls for the Paulines, in which he placed their monasteries under special protection. In addition to the bulls for Annhausen , Goldbach and Langnau , the one from May 11, 1418 for the Bonndorfer monastery has been preserved. In 1482 the monastery buildings burned down. In the course of the Thirty Years War , most of the archive material was brought to Klingnau ( Sion Abbey ) for safety in 1631 , where it was burned in 1632.

St. Blasian Rule

By 1612, the St. Blasien monastery had taken over the entire imperial rule of Bonndorf . From the further fate of church and monastery, disputes are known, with St. Blasien as well as with the community, about tithe rights, “payments to the messmer, schoolmaster, night watchman, the heavenly bearers in processions, for building maintenance and church supplies, (...) sermons and confession letters, the authenticity of stock books, the challenge to the Wolfurt Foundation, (...) the carnival cakes promised to the local board , “the use of abandoned iron cemetery crosses, and finally church asylum . According to canon law , the Pauline monastery as a holy place had this privilege. Asylum seekers were not allowed to be removed with cunning or violence. The abbot of St. Blasien found himself in a conflict of interest. As an ecclesiastical dignitary he had to refrain from anything that could be viewed as an attack on the right defended by the Catholic Church; as the judge, he had to prevent the asylum practice from getting out of hand. In a contract dated March 10, 1668 under Abbot Otto III. It was agreed that the church and monastery, along with the garden, should be a sanctuary for delinquents who had to expect life or corporal punishment, but not for others, such as debtors harassed by their creditors. In addition, the Paulines were granted school rights.

In 1697 the Steinen Seege sawmill was owned by the Pauline monastery in Bonndorf. From 1721 to 1732 Columban Reble was appointed head nurse . With Martin Gerbert , who entrusted the Pauliner with the construction of the hospital and workhouse in 1789, the disputes largely ended. From today's perspective, Spital Bonndorf is one of the first more modern hospitals. The infirmary (Leprosorium) in Wellendingen, which had existed since 1662, was closed. In addition, the Paulines looked after the branch churches in Wellendingen and at times the parish of Boll .

Up until the beginning of the 18th century there was usually only one other monk in Bonndorf in addition to the prior, but the number then grew to three to four monks. In 1718 the order introduced the common choir prayer and the cloister, built an extension in 1721 and tried independently to enlarge the monastery to eight monks. Further expansion plans failed due to resistance from St. Blasien and the demand for expansion of the inadequate parish church. Several years of unsuccessful negotiations followed to relocate the convent to the convent , which St. Blasien had acquired in the meantime. In 1731 the entire parish and monastery church as well as other monastery buildings were partially rebuilt and the abbot of St. Blasien allowed a size of eight monks, which was increased to ten in 1736. In 1739 the monastery received relics of the catacomb saint Donatus, but the altar was removed again in 1783. In 1743 three new altars were erected with pictures by Jakob Karl Stauder . From 1755 the worship of a copy of the miraculous image of Czestochowa began , the original of which is in the monastery on Jasna Góra .

While most of the income from other Pauline monasteries consisted of real estate and feudal taxes, Bonndorf covered around three quarters of his expenses from parish income, mainly from tithing . Due to the coalition wars, the economic situation of the monastery deteriorated, so that around 4,000 guilders in income were offset by expenditure of more than 5,500 guilders. In 1802 the monastery was forced by St. Blasien to give up its own economy, to reduce expenses and to transfer three monks to foreign pastoral care.

resolution

After the Pauline monasteries of Langnau and Rohrhalden had been dissolved as early as 1785 and the Grünwald and Tannheim monasteries followed in 1802/03 , Bonndorf was the only Pauline monastery outside of Poland. With the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803 Bonndorf and with it the monastery came to the Order of Malta before it was claimed by the Kingdom of Württemberg in the Peace of Pressburg at the end of 1805 . On July 30, 1806, the Württemberg official Carl Friedrich von Dizinger received the order for the "unfinished" dissolution of the Bonndorf, Berau , Stockach and Radolfzell monasteries , as they had already fallen back to Baden with the Rhine Confederation Act . When he arrived in Bonndorf the next day, however, he “soon convinced himself that the liabilities far exceeded the monastery’s assets” and he went straight to Berau.

After the abolition of the monastery had been decided on March 25, 1807, the final dissolution did not take place until April 23, 1807. Prior and Subprior were retired, three former monks and two vicars remained for pastoral care in Bonndorf and the remaining three monks became other parishes - or assigned chaplain positions. The “rather insignificant book collection” was to be sent to the University of Freiburg .

Aftermath

The cemetery, which until then had been by the monastery, was moved to today's city garden in 1807, to which the palace chapel was also moved a few years later . The organ of the monastery church, which was first documented in 1783, was moved to Grafenhausen in 1834 to make room for the organ from the former Berau monastery church.

On the evening of July 18, 1842, a fire broke out in the house of the church fund manager, which destroyed seven private houses as well as the former two-winged convent building and the parish church to the ground. The new parish church of St. Peter and Paul was laid in 1846 a little above the previous location at a right angle to the previous complex.

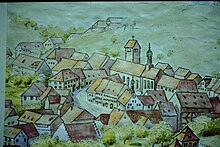

Only a few stacks of handwritten materials and a number of books remind of the descendants of the hermit Paul today in Bonndorf. The Martinsgarten with the Martin-Gerbert monument by Franz Xaver Reich is located on the site of the former monastery . In Schloss Bürgeln in Schliengen, which was also completed in 1764 under Martin Gerbert, there is also an over- port that shows the condition of the Pauline monastery from 1660.

According to Josef Durm , the figure on the Marienbrunnen in the city center is said to come from the Pauline monastery. Hans Matt-Willmatt wrote in his Berau village chronicle in 1969 that “the statue of the Virgin Mary made of yellow sandstone, which stood in the cloister garden [of Berau monastery], was used as a fountain figure for the town hall fountain” after the Bonndorf town council had requested this.

The incorporation of the parish church by the monastery from 1402 and its aftermath in the secularization formed the basis of the legal dispute between the Bonndorf parish and the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1927 , over its participation in the heating of the church and sacristy and electrical lighting. This legal dispute was ended in 1927 by the Bonndorfer settlement .

literature

- Joseph König : On the history of the foundation of the Pauline monastery in Bonndorf . In Freiburg Diocesan Archive , Volume 14, 1881, pp. 207–224 ( digitized version ).

- Franz Xaver Zobel: On the history of the Pauline monastery in Bonndorf on the Black Forest. In: Freiburg Diocesan Archive, Volume 39 (1911), pp. 362–378 digitized

- Hermann Schmid: The Pauline monastery in Bonndorf (1402–1807) . In: Schwarzwaldverein Bonndorf (Hrsg.): 100 years Schwarzwaldverein Bonndorf. Contributions to the Bonndorfer and Wutach home history and the club history , 1985, pp. 15–24.

Web links

- Paulinerkloster Bonndorf in the database of Monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

Individual evidence

- ↑ Joseph König: On the history of the foundation of the Pauline monastery in Bonndorf in the Freiburg Diocesan Archive , Volume 14, 1881, p. 213.

- ^ Hermann Schmid, Das Paulinerkloster in Bonndorf (1402–1807) , In: 100 Jahre Schwarzwaldverein Bonndorf , 1985, p. 15.

- ↑ Elmar L. Kuhn : The German Province of the Paulines, 14. – 16. Century. (PDF) January 8, 2002, p. 5 , accessed January 23, 2016 .

- ^ Hermann Schmid: The Pauline Monastery in Bonndorf (1402-1807) , In: 100 Years of the Black Forest Association Bonndorf , 1985, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Main conclusion of the extraordinary Reichsdeputation of February 25, 1803

- ^ Matthias Erzberger : The secularization in Württemberg from 1802-1810 . Deutsches Volksblatt, Stuttgart 1902, p. 318 f. Full text / preview in Google Book Search.

- ↑ Artur Riesterer: The foundation stone of the church was laid 150 years ago , Badische Zeitung of May 7, 1996, this refers to: Memoirs of Augustin and Nikolaus Kern from Bonndorf 1768–1849

- ^ Hartwig Späth: "Festschrift" organ consecration on January 13, 1985 . Bonndorf 1985.

- ^ Bonndorf, July 18. In: Freiburg newspaper . July 19, 1842. Retrieved January 17, 2016 .

- ↑ Hermann Schmid, Das Paulinerkloster in Bonndorf (1402-1807) , In: 100 Jahre Schwarzwaldverein Bonndorf , 1985, p. 24.

- ↑ Information via email from castle guide Hartmut Potthoff.

- ^ Franz Xaver Kraus , Josef Durm : The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden . Volume 3: The art monuments of the Waldshut district , Academic Publishing House Mohr, Freiburg im Breisgau 1892, p. 8 .

- ^ Hans Matt-Willmatt, Emil Beck: Berau in the southern Black Forest . H. Zimmermann, Waldshut-Tiengen 1969, p. 44.

- ^ Reichsgericht: Judgment file number: IV 264. Case: State as legal successor to the secularized monasteries. Opinionioiuris.de, November 22, 1920, accessed April 1, 2016 .

Coordinates: 47 ° 49 ′ 13.1 ″ N , 8 ° 20 ′ 29.8 ″ E