Waldshut Capuchin Monastery

| Waldshut Capuchin Monastery | |

|---|---|

| medal | Capuchin |

| founding year | 1654 |

| Cancellation / year | 1821 |

| Start-up | new order |

| Patronage | |

| St. Anthony | Website |

| - | |

| location | country |

| Germany | region |

| Baden-Württemberg | place |

| Waldshut | Geographical location |

The Kapuzinerkloster Waldshut is a former monastery of the Capuchin Order in the town of Waldshut am Rhein , Germany .

The foundation stone was laid in 1654. The Franciscan material equipment, which, however, included a coronation of Mary by Johann Melchior Eggmann , an extensive library and two princely heart burials, is lost or has been scattered. The Waldshut Capuchins were firmly involved in public life in the city. They also played a major role in the history of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province.

The building complex, which had been completely rebuilt several times since it was abolished in 1821, was used by the Waldshut Hospital Fund from 1859, which later became the hospital and today's Hochrhein Clinic .

history

founding

The nationwide establishment of Capuchin monasteries in Upper Austria was an act of the Counter Reformation that began after Leopold V took office . The French War from 1633 to 1648 and the subsequent French occupation of the forest towns until October 18, 1650 interrupted the program, which was resumed under Leopold's son Ferdinand Karl . Under the maxims of faith and loyalty , the Habsburg corridor, which is largely surrounded by Protestant areas, was to be confessionally and ideologically consolidated. In 1633 the occupations of the forest towns had largely defected to the Swedes.

The order or permission of the sovereign was insufficient for the foundation. In addition, the Capuchin constitutions required the approval of the provincial chapter or the definitory, which meets annually in different places, the approval of the diocesan bishop, the approval of the general minister and his definitory, and finally the approval of the Holy See.

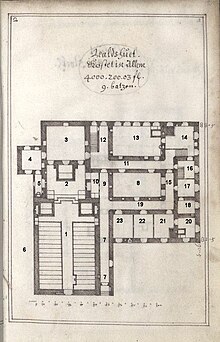

Under the supervision of the Basel prince-bishop Johann Franz von Schönau , the Swiss Capuchin Province took over the planning, construction and occupation of the three founding monasteries in Rheinfelden , Laufenburg and Waldshut . The Franciscan Sisters were already represented in Säckingen . A pious rivalry between the cities of Laufenburg and Waldshut for the speed of construction is a fama. For organizational reasons, priority was given to the Rheinfelden monastery , which was therefore completed in 1657. The handwritten codex from the Fürstenbergische Hofbibliothek Donaueschingen , the Codex Donaueschingen 879, which was started before 1668 and completed after 1673, documents the Swiss-Austrian joint project. The work is attributed to the master builder Probus Heine from Pfullendorf after comparing scripts . As the master builder of the order, Probus Heine was also responsible for the construction of the Waldshut monastery complex. The most important donors and sponsors of the Waldshut Capuchin monastery were Franz Ludwig von Roll (Bernau) and his wife Maria Agnes from the family of the governor Marx Jakob von Schönau , who died in 1643 , with 1000 guilders. The prince abbot of St. Blasien Franz I. Chullot , the landgrave in Klettgau Johann Ludwig II. Von Sulz and citizens and officials of the city made further foundations . The city council of Waldshut provided logistical support and through the delivery of natural produce. For the construction of the monastery in Waldshut, 4,203 guilders and 9 Batzen were estimated.

The planning goes back to the year 1650. In 1652 the area was given to the Capuchins. On June 14, 1654 the foundation stone was laid by Franz I Chullot. At the same time a stone cross was erected. Construction of the cloister began on October 4, 1655. According to Romuald von Stockach, the convent church was consecrated on September 7, 1659 by the Constance Bishop Franz Johann Vogt von Altensumerau and Prasberg . The presbytery was placed under the patronage of St. Anthony of Padua and the lay church under the patronage of Beata Virgo Maria Immaculata .

Important events

- 1654 Laying of the foundation stone and erection of the cross with the crucifixion tools.

- In 1656, the patron of the monastery, Johann Franz von Schönau, died of dropsy in Pruntrut shortly before he was promoted to cardinal dignity . In his will, the prince-bishop ordered a heart burial in a silver capsule, which, at his request, was to be walled in in the presbytery of the Waldshut Capuchin monastery under construction.

- In 1659 the monastery was occupied by eight priests, most of whom were withdrawn from the Rheinfeld Capuchin monastery.

- In 1664, the cities of Rheinfelden, Laufenburg and Waldshut submitted a joint request to Archduke Sigismund Franz to connect their Capuchin monasteries to their own front-Austrian order province, as they did not want to be comforted and spiritually provided by the "disaffected Swiss".

- In 1668 the 27 Upper Austrian monasteries split off on April 16 at the provincial chapter of the Swiss Capuchin Province in Wyl and founded the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province .

- In 1681 the Capuchin Marco d'Aviano, invited by the council and the citizens and enthusiastically received, gave his blessing.

- In 1687 Johann Ludwig II. Von Sulz also ordered his heart burial in the presbytery.

- In 1688 the Capuchins brokered a French invasion.

- In 1697 the grammar school, the place where the novices from Upper Austria were trained, was moved from Markdorf to Waldshut until 1739.

- In 1726, the intercession of the priests and the clergy was assigned to contain the fire in the town, which claimed 46 houses. The wind died down in response to their prayers.

- In 1746 the monastery, which was affected by the French and Bavarians during the War of Succession, was extensively renovated.

- The Fidelis Chapel was first mentioned in 1754.

- In 1758 there was a dispute with the city over the establishment of Stations of the Cross in the lay church.

- In 1772, with the court decree of March 20, Maria Theresa only allowed born Austrians to hold leadership positions in the order.

- In 1781, the last Definitor of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province, RP Reinhard von Waldshut, carried out the separation of the Fürstenberg Capuchin monasteries from Vienna on March 24th.

- In 1781, the court decree of June 8th prohibited the admission of novices.

- In 1784 the city used itself in view of the threatened repeal.

- On February 1, 1788, collecting alms and selling amulets and tufts of herbs was prohibited. The fathers were supported by the religious fund.

- In 1796, retreats between the French army on the Rhine under General Tarreau and Austrian units under General Wolf spread to the monastery.

- In 1801 the monastery was transferred to the Order of St. John under the compensation plan under the Treaty of Luneville and Amiens .

- 1803 was reassigned to the Order of St. John by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss .

- In 1804 the lay church was used as a provisional town church in shifts until 1808 due to a debacle in the construction of St. Marien.

- In 1806 the monastery was transferred from the sovereign Principality of Heitersheim to the Grand Duchy of Baden on July 12 with the Rhine Confederation Act.

- In 1807, the grand ducal government of Baden expanded the extinction budget to include a ban on immigration.

- In 1809 RP Werner Fechtig von Rottenburg, Guardian von Waldshut and last Provincial of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province, died on November 12th in Waldshut.

- In 1814, due to a typhus outbreak within the Schwarzenberg Army, the convent wing was converted into an epidemic hospital and a two-story large latrine system was added on the west side. The convent was used as a military hospital until 1816. The lay church served as a material store.

- In 1817 the grand ducal government ordered the relocation of the last three brothers to the Staufen convent .

- In 1820 the last Guardian of Waldshut P. Azarias died.

- In 1821 the Waldshut Capuchin monastery was abolished on November 7th after the relocation of the remaining Father Sabinus to the religious hospice in Staufen im Breisgau and the release of the last lay brother from his vows.

Tasks and activities of the Convention

The Capuchin priests temporarily helped out within the Waldshut deanery. However, they are not listed in the statutes of the Waldshut chapter of 1749. They looked after the Waldshut hospital and the workers at the hammer mills in Albbruck. From 1670 onwards, after the compulsory parish was abolished, confession was accepted. As a result, the Upper Austrian Capuchin monasteries reported that up to 800,000 confessions were taken each year. The pastoral care of the sick and dying was, according to the custom of the time, almost exclusively entrusted to the Capuchins. The associated influence on the drafting of wills brought them repeatedly the accusation of inheritance sneaking. Capuchins took special care of inmates and convicts in prisons and accompanied those condemned to death on their last walk. Heinrich von Kleist processed this task in the 20th anecdote (from the Capuchin) in the 53rd Abendblatt, dated November 30, 1810.

Another focus was the mission, which extended deep into the reformed cantons of the Confederation. This led to repeated negotiations in the Federal Diet, for example on Easter Tuesday 1735 after a sharp sermon by a Waldshut Capuchin. Capuchins from the Swiss Capuchin Province who had become conspicuous in the Confederation were repeatedly transferred to Waldshut. A brother of the Zurich Reformed preacher Johann Kaspar Lavater visited the Waldshut Capuchin monastery in 1777 with the intention of converting.

Due to an unspecified scandal, the grammar school for novice training in the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province was relocated from Markdorf to Waldshut between 1697 and 1739.

The lay brothers baked hosts on behalf of the Waldshut Church Fund. The last lay brother, Sidonius Fuchs, applied for a dispensation from religious vows on September 22nd, 1822 and successfully switched to the wafer bakery with his wife.

The sale of various monastery works such as scapulars and crosses and herb bushes contributed to the popularity of the Capuchins among the people. The Capuchins saw themselves as professional exorcists, even if one can think differently and scoff at them. A Capuchin from Waldshut appears in the local folk tale of treasure and spooks in Castle Homburg.

On public occasions, such as the ceremonial translation of the imperial-royal-also-ducal-Austrian highest corpses in 1770 , the Capuchins appeared with their carrying cross. The Capuchin preacher Marco d'Aviano was invited by the council on the occasion of his passage from Constance via Stein to Baden in 1681 and gave the city his blessing. The Capuchin Lecturers taught converts. The public baptism of the Jew Aron from Timisoara , who was taught by Father Lektor, with godparents from the local nobility on May 27, 1767, was an anachronistic event in the Age of Enlightenment.

The Capuchin Order did a great job in caring for the plague sufferers in the epidemics of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Pastoral care and nursing merged into one another. Assistance from the Waldshut Capuchins in the event of epidemic outbreaks and work in the nearby leprosy house can be assumed.

Economic situation

According to the Constitutions, the brothers only used the buildings that were formally owned by the sovereign. When it was founded, the monastery was equipped with 2 Jauchert and 37 Ruten properties. In return for pastoral or nursing activities, the monastery received alms in kind, which were sometimes capitalized. The monastery, which in spite of the location itself did not grow wine, received two Saum wine annually from the hospital fund and another four Saum from the parish. This also supplied other natural produce such as the grain for baking the host . According to the city's accounts, the city took over the cost of wax and oil from 1731 to 32 and capitalized the free meals of the brothers on Corpus Christi and the church consecrations with twelve guilders. The assumption of benefices and the industrial pastoral care in Albbruck brought additional income. There were also numerous foundations. The Freiherrlich Roll'sche Foundation for the Waldshut Capuchin Monastery was the subject of long-standing disputes between the government of the Grand Duchy of Baden and the Canton of Aargau from 1809, which ended in 1819 after a series of settlements.

Whenever possible, objects for daily use were made themselves or exchanged with other monasteries in the province. Cloth and fabrics were obtained from the weaving mill of the Capuchin monastery in Rheinfelden.

Development and end of the monastic community

The Capuchin communities were made up of three groups: the studied cleric who trained in the gymnasium Fathers and the untrained Fratres . Their ratio in the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province was about 1: 4: 2 between 1681 and 1821. According to the Architectura Capuzinorum, the monastery offered space for 22 brothers. However, it soon became apparent that the monastery buildings were too narrow. The actual number of brothers is unlikely to have exceeded twenty until the 1780s. At the time of the maximum strength of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province, 646 Capuchins lived in 35 monasteries.

After the ban on accepting novices in 1781, replenishment was only possible by moving in. The admission of two Alsatian friars at the time of the French Revolution is known. Brother Ignatius from Laufenburg was transferred to Waldshut because of his anti-reformatory sermons. After the abolition of the Laufenburg Capuchin monastery, he was followed in 1802 by ex-provincial P. Azarias from Säckingen to Waldshut. Not until 1801 was the acceptance of novices allowed again under restricted conditions. These restrictions were completely suspended during membership of the Principality of Heitersheim between 1802 and 1805, so that the admission of the last lay brother Sidonius Fuchs (1775–1861) was still possible. In May 1804 the last Guardian of the Capuchin Monastery of Rheinfelden, P. Reginald Fendrich, moved there until his death in 1811. When the monastery was used as an epidemic and military hospital from 1814 to 1816, the four remaining brothers Azarias, Reinhard, Alexander and Sabinus were accommodated in the rectory. Sabinus, the last Waldshut Capuchin, moved to the order's reception hospice in Staufen in autumn 1821, where he died in 1822.

Capuchins and Saltpeter

In the second quarter of the 18th century there was again considerable unrest among the natives of the county of Hauenstein. The unrest culminated in 1745 when the town of Waldshut was besieged by the troubled Hauensteiners under the leadership of Hans Wasmer, known as "Gaudihan". The march of the saltpetre and the storm of Gaudihan on the lower gate took place directly in front of the monastery walls. It is not known to what extent the monastery standing outside the city walls was involved in the conflict.

During the protracted mission of the Hauensteiner, the Capuchins of Waldshut and their successors did not achieve any significant successes until the end of the 19th century. They often offered confession to the convicted ringleaders in vain and accompanied the Hauensteiners' deportation trains. In the end, the only thing left for the Capuchins to do was to express their regret at the ignorance of these poor and deluded people.

The monastery in wartime

At the beginning of the War of the Palatinate Succession , 200 horsemen and 500 infantrymen from the French fortress of Hüningen set out on a military excursion to Waldshut on December 10, 1688 . The warned citizens and the crew had crossed the Rhine in good time before the arrival of the French on December 22nd and left the negotiations to the Capuchins. In fact, the Capuchins reached an advantageous conclusion in their negotiations with the commander François-Joseph Comte de Clermont-Tonnerre, but this was not accepted by the commander in Hüningen. In general, the Capuchins were held in high esteem by the Swedes and the French as early as the Thirty Years' War and were generally treated with respect. At the request and kneeling of the Capuchins, Marshal Crequy put an end to the burning and looting of the women's monastery and the town of Säckingen, which had already begun.

During the War of the Austrian Succession and the Wars of the Revolution , the monastery was cleared and made available as barracks for the troops passing through. On July 18, 1796, a division of the French Army on the Rhine under Adjutant General Marie-Charles-Henry Perrin (1769–1804) was received in front of the monastery with a freedom tree. When the French withdrew on October 4, 1796, the Karaczay'schen Chevauxlegers under the command of Colonel Count Maximilian Friedrich von Merveldt lifted 170 French infantrymen barracked in the monastery and the city after an exchange of fire. On the following October 19, Giulay's Freikorps attacked the rearguard of the French entourage returning from Bavaria below the monastery . Only when a French cannonball hit the wall of the monastery ended the battle in which 50 French were killed.

During a typhus epidemic at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1814, the monastery was used as an epidemic and military hospital until 1816. 165 soldiers and 60 citizens died in the epidemic. The lay church and the presbytery were used as storage facilities during this period. The last four brothers were only allowed to use the oratorio .

Secularization and repeal

The long process of secularization of the monastery was initiated in June 1781 by the ban on accepting novices (extinction budget) from Vienna. In addition, there was a threat of closings due to mergers. After repeated submissions from the city of Waldshut, the Freiburg government applied in 1785 to leave 13 priests and 3 lay brothers to help out in the pastoral care of the Waldshut Capuchin Monastery. Under Franz II, the acceptance of novices was allowed again from 1801. The Capuchin monasteries in Austria, which were drained in terms of personnel and economy, only gained access sporadically.

In the provisions of the Peace of Lunéville and the Peace of Amiens , the Waldshut Capuchin Monastery was awarded to the Sovereign Knights and Hospital Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and Malta for compensation for lost property on the left bank of the Rhine. The provisional civilian possession by the Order Chancellor Ittner from Heitersheim took place on November 15, 1802, five months before Duke Ercole III took possession of the Breisgau . of Modena in March 1803. Due to the provisions of the Peace of Pressburg , the monastery fell to the Grand Duchy of Baden with the mediatization of the Principality of Heitersheim , which again put it on the extinction budget. The last incumbent Provincial of the Province Werner Fechtig died in Waldshut in 1809. The last Guardian of Waldshut P. Azarias died in 1820. After the last Capuchin friar had been relocated to the central hospice of the order in Staufen and the last lay brother was released from his vows, the monastery was finally abolished on November 7th, 1821 after a last ceremonial act. On December 19, 1821, the church utensils were publicly auctioned in Waldshut.

Fall of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province

In the wake of the secularization movements, the Waldshut Capuchin Monastery quickly developed into one of the last reserves of the declining Front Austrian Order Province, the last top leadership of which died in Waldshut. The reasons for this lie in the good local network of the monastery. Despite the political support, the monastery community survived to the end, as it remained arrested in the Rosary and Calvary Movement of the 17th century and in recent years has got into a dissent with the reform-oriented national Catholic priests of the deanery, who ultimately saw the order as a "parasite the Klerisey ”. They paved the way for the last lay brother into civil society with satisfaction.

The last resting place of the Capuchin Fathers

The first 28 burials of the friars took place in the old crypt from 1658 to 1733. From 1733 there were 16 more burials in the new crypt under the Fidelis Chapel. Due to the Josephine burial laws, the brothers who died from 1786 were buried in the churchyard due to the obligation to cemetery.

The chaplain of the Gottesackerkapelle Achill Beck , who was entrusted with the profanation of the Waldshut Capuchin monastery , a former clergyman of the Franciscan monastery in Überlingen , which was also closed in 1811 , laid a burial site near the north wall of the Gottesackerkapelle in 1822, in which the bones of the Capuchins from the old crypt and the one below the Fideliskapelle were built Ossuary were transferred. In 1825 Beck received the cardiotaphs broken out by Frey-Herosé , the heart capsules and the epitaph from the Prince-Bishop of Basel. Achill Beck walled up the capsules in the chapel wall and fixed the marble epitaph of the prince-bishop in front of it . Achill Beck himself was buried next to the memorial after his death. Of the memorial in Waldshut, only the cardiotaph of the prince-bishop, which is now placed on the cemetery wall after being temporarily moved to the interior of the chapel, has survived.

Later and current use of the building

The monastery complex came into the possession of the Aarau industrialist Daniel Frey, who set up a chemical factory in the buildings for the production of vitriol oil . As technical director of the factories in Aarau and Waldshut, his son Friedrich Frey-Herosé was in charge of the renovation work, which resulted in substantial, substantial interventions. On June 21, 1825, Frey-Herosé appeared unannounced in the rectory at Pastor Joseph Benedikt Sohm's and had the cardiotaphs that had broken out of the wall of the presbytery of the Prince-Bishop of Basel and the Landgrave of Sulz, including the removed heart capsules, unloaded.

The establishment of a chemical factory for the production of sulfuric acid within the Grand Duchy of Baden was a pioneering industrial achievement. The reasons for the failure of the project are not known. The customs barriers, the local guild associations, which were only dissolved in 1837, and an industry that only developed much later in southern Baden were well-known resistances. Since the second location in Waldshut was not profitable for Frey-Herosé in the medium term, he sold the building complex to the restaurateur Josef Hierlinger in 1834, who converted it into a restaurant and hotel Rheinhof by 1836 . The former lay church was converted into a stable by the restaurateur. A lithographic view by Godefroy Engelmann from the 1840s shows the structural changes that still determine the facade today. An upper floor was moved into the Fidelis chapel and the lay church. The church windows and the windows of the monastery wing were given uniform medium sizes. The gable crosses were replaced by lightning rods and the roof turret removed. The entrance corridor, the latrine system from the Napoleonic era and the surrounding wall were completely removed.

In 1857 the Rheinhof was acquired by the Spitalfond, which opened the first Waldshut hospital in 1859 after a two-year renovation period in the building complex. The old hospital chapel, which still exists today, with arched windows and renewed roof turrets was built into the former chapter room in 1861 . The also vaulted presbytery is only cut into the entrance area on the ground floor. In the gallery it has the old extension. The chapel, consecrated in 1862, is under the patronage of St. Vincent de Paul .

The expansion of the Waldshut Hospital in the 20th century led to more and more uses and changes. At the beginning of the 1975 years, demolition was discussed. After further renovations, the former monastery complex has been divided up since 1985 and is rented out. A pharmacy was set up on the ground floor of the former lay church. The common room of the emergency room with tea kitchen is located in the former monastery kitchen. In the former refectory of the available ambulances and ambulance . In the other parts of the building there are medical practices and a medical care center run by the hospital. The chapel was renovated, furnished in the style of the late 20th century and kept as the second hospital chapel.

The monastery library

Structure of the book inventory

According to Romuald von Stockach, the later canon of Freising, Franz Joseph Anton von Roll (1653–1717), is said to have built the monastery library. A Basel edition of the Chronicon des Antoninus (Florentinus) from 1491 with an ownership note of the monastery in the catalog of the Archdiocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart refers to an inventory of cradle prints. Bookings from the possession of the last Klettgau Landgrave von Sulz can be inferred from a note by Joseph Bader , who quotes entries in the welcome book of the Küssaburg with an entry in the ownership of the Waldshut Capuchin monastery. In a will of December 17, 1730, the provost of Wolfegg and former pastor of Donaueschingen Johann Theodericus Straubhaar bequeathed his library to the Capuchin monastery in his home town of Waldshut.

Library catalog from 1747

On the occasion of the monastery renovation in 1746, a catalog of the monastery's printed holdings was created the following year. The inventory then comprised 2200 titles in various formats in 19 departments. The titles to be emphasized include a Lyons Holbein Bible and the lucky book with the illustrations by the Petrarca master (Augsburg 1539). The vast majority comprised theological titles in Latin and German. The lists are arranged according to the authors' first names: Bibles (57 titles), Commentaries (104 titles), Church Fathers (56 titles), Morals (139 titles), Poles (16 titles), Historical works (195 titles), Spiritual works ( 499 titles), Textbooks (44 titles), Canonical writings (27 titles), Civil literature (16 titles), Miscellaneous (59 titles), Philosophy (30 titles), Ritual writings (36 titles), French books (14 titles), Italian Books (105 titles), Catechisms (14 titles), Interpretations of the Rules (8 titles). As can be seen in general for Capuchin libraries of the time, it was an anti-reformist specialist library with numerous controversial texts. Popular authors such as Abraham a Sancta Clara and Johann Nikolaus Weislinger were each represented with several titles. Own bindings of the Waldshut Capuchin monastery are not known in the literature. Central European Capuchin monasteries of this era preferred brown leather bindings with a few frets and one or two blind stamps.

Dissolution of the library

The library was sold after the abolition of the monastery in 1822. The three sales lists of the books from 1822 mainly contain printed titles from the 17th and 18th centuries. From Bader's note it can be concluded that the more important works were given to the court library in Karlsruhe in advance. According to the provisions of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, the court library in Karlsruhe was given the right to make the first selection from the monastery and monastery libraries. The unwanted books were offered to the university libraries in Freiburg and Heidelberg. The secularized Kapuzinerbibliothek Waldshut was taken over in 1822 in the final phase of the transfer of ownership.

Artistic equipment and church equipment

The early baroque furnishings of the monastery were functional and modest according to the rules of the Capuchins. However, less was saved in the artistic equipment than in the materials used. Chalices from Capuchin churches are made of base metal and are decorated with engravings instead of forging and precious stones. Instead of gilded trimmings, measuring jugs made of glass or baked clay were used.

Bell and sundial

The Capuchin Building Regulations in Chapter 6 of the Constitution only permitted the use of a single small bell, weighing no more than 150 pounds. A small octagonal roof ridge was sufficient for this. The 148-pound bell of the Waldhut Capuchin Monastery, probably made in the foundry of the Waldshut family Grieshaber in 1731, with the images of the crucified Savior and the Conception of Mary above the inscription S. Antonius Pater Capucinorum. was acquired at the auction of December 19, 1821 by the community of Kadelburg for the newly built parish church of St. Martin. It was lost in a metal confiscation under the fourth ordinance of March 4, 1940 for the registration of non-ferrous metals . It is not listed among the region's bells returned from Hamburg after the war.

In Capuchin monasteries in the province, a sundial was usually installed on the south wall of the nave to indicate the time. It has not survived in Waldshut.

Equipment of the lay church

In 1821, the community of Kadelburg not only acquired the bells for their new church, but also important parts of the sculpture program of the Waldshut Capuchin monastery and its baptismal font. The cross of the Capuchin Fathers is now a crucifixion group with renewed beams above the altar of the Church of St. Martin in Kadelburg, flanked by the statues of Mother Mary and the disciple John. The original location above the choir lattice between the lay church and the psallion choir and the former arrangement result from sheet 13 of the Architectura Capucinorum in the Codex Don. 879. Marin Gerbert states that the Capuchin fathers carried the cross with them on solemn occasions.

The simple octagonal baptismal font made of sandstone with a renewed base in St. Martin is closed by an octagonal cover with the IHS inlaid. The original lid is a typical work by the Waldshut Feinlein workshops from the 1680s. Only the key plate dates from the 1820s.

St. Martin in Kadelburg has been rebuilt several times over the last few decades and has been made simpler with the loss of substance.

Equipment of the Fidelis Chapel

Unfortunately, one can only speculate about the furnishings of the Fidelis Chapel. It would be conceivable, like in Rheinfelden, an altar leaf with an apotheosis of St. Fidelis. A central sculpture would also be possible. For this thesis there is a Fidelis statue that was forcibly reworked and shortened to an Antonius sculpture in a corner of the Assumption of Mary in Tiengen.

Frescoes

Sheet 12 of the Architectura capuciorum in Cod. Don. 879 shows the choir wall between the lay church and the presbytery, the upper section of which is painted on the chancel side with a crucifixion motif with angels who collect the blood of the stigmata and depictions of saints.

At the renovation 1746 was from unconventional Rorschacher Wanderfreskanten Johann Melchior Eggmann an illusionary Marie crowning made, a subject who is to be understood well as political signal the end of the Austrian succession war. The frescoes fell victim to the first renovation work. Another (now whitewashed) color-intensive painting of the hospital chapel in the presbytery combined with the chapter room was carried out in 1928 by the local church painter Karl Bertsche.

The heart burials

The inner silver heart capsule of the Landgrave von Sulz, removed by Pastor Sohm in 1825, is shown in the Klettgau Museum Tiengen . The cardiotaph of the Landgrave von Sulz, made of white marble, is also in Tiengen after being repositioned several times. The cardiotaph of the Prince-Bishop of Basel is set up at the entrance of the Waldshut Gottesacker. The epitaph of the prince-bishop described by Romuald, the inscription of which began with the line Hay Viator and ended with the chronodistich: Manes aD Cor LoqVI (1656), has been lost. Since the first line of the epitaph addressed a traveler as Viator, it can be concluded that the epitaph was set up outside the enclosure in the lay church. The wording in the will of the Landgrave von Sulz shows that the heart urns were embedded in the walls of the presbytery above the altar.

description

Outdoor area

The monastery grounds were in front of the Lower Gate and bordered the city moat. The district plan of Waldshut, created in 1775 by the geometer Johann Hühnerwadel, shows the area in the form of a dragon square with extension to the southwest. It was bordered on the north side by Heerstrasse, in the east by the city moat, in the south by the Rheinhalde and in the west by a green area. The elevation created by the city architect Sebastian Fritschi after it was canceled shows the area surrounded by a wall at a distance of only a few meters from the monastery complex. A small forecourt opened up the north facade and the entrances to the lay church and the corridor of the convent building. Within the walls there was a small tree garden to the east, at the level of the choir of the presbytery the burial place of the Capuchins. The tapering strip along the Rheinhalde served as a herb and medicinal plant garden. In the south there was the farm yard and in the north the entrance to the convent, which could be reached through a gate in the northwest. At the transition from the garden to the farmyard there was a fountain with two troughs.

Lay church, choir and presbytery

The type of church follows the Venetian-Tyrolean scheme of the contemporary Capuchin churches. Based on the plans for the Waldshut monastery in the Architectura Capucinorum, the rectangular lay church (1) stood in the northeast of the complex. In the small rectangular wing of the building with two cross vaults attached to the south, the presbytery (2) separated by the choir grille under the transverse arch and the psalier choir (3) to the south. The choir of the Psalms and the presbytery were connected by two windows that were closed during the activities and a doorway. The two windows made confession and communion possible. The means of wine, water and bread needed for liturgical reasons were exchanged through the trullet. On the convent side, an overhead window enabled a view of the lay church. The pulpit of the lay church was reached via the library (24) on the upper floor of the convent wing. To the east, a small sacristy (4) and a corridor with a wall basin (5) were added to the choir and the presbytery. On the west side of the presbytery was the oratory (10).

Fidelis Chapel

In 1729 Gurdian Fidelis , who was regarded as the first martyr of the Capuchin Order, was beatified and canonized on June 29, 1746 by Pope Benedict XIV. Together with Camillus von Lellis. A special local reference resulted from the fact that the Waldshut Valerius Bürgi (1577–1635) was a classmate of St. Fidelis and witness in his beatification process. To commemorate martyrdom in Switzerland, the Fidelis Chapel (6), first mentioned in 1754, was attached to the east wall of the lay church at a right angle. The building was built after the canonization of 1746. Since the Fidelis chapels in Laufenburg and Rheinfelden were consecrated in September 1750, it can be assumed that Waldshut will be completed at the same time.

As in the Capuchin monastery in Rheinfelden and in the Capuchin monastery in Laufenburg, a communal crypt was laid out under the Fidelis Chapel . Usually such capuchin tombs were laid out as shallow barrel vaulted halls with lateral columbaria in three or four zones. These offered space for up to 60 burials.

Convention wing

The four-wing convent wing, the Quadrum, west of the churches was accessed through the entrance corridor (7). The narrowed east wing (9) contained the oratorio (10) with a window to the psallier choir. A half-open gallery (9) was laid out on the side of the cloister courtyard (8). A door to the enclosure led to the closed gallery (11) of the south wing, which opened up the staircase (12), the brothers' heated refectory (13) and the monastery kitchen (14). In the west wing, which was again outside the enclosure, there was another closed gallery (15), which led to the washroom (17) and the Loca secreta (18) behind it. The pantry in front of it, accessible from the kitchen, was connected to the fruit chute and the cellar via a second staircase (16). In the north transverse wing, which in turn was accessed through a half-open gallery (19) outside the enclosure, to the west were the pilgrims' room (20) with an oven, the dining room for the poor and needy (21), a visitor or confessional room (22) and the consulting room (23).

On the upper floor of the quadrum was the library (24) with access to the pulpit of the lay church, a small room as a passage to the infimeria (25), the foresteria (visitor room) (26), (27) and (28) for guests and for the Visitors, the domitorium with twenty-two individual cells that only reveal the garden and inner courtyard (29), the laundry room (30), the tailor's shop (31), the infirmary with sick (32) and death rooms (33), from which Viewing slits enabled a line of sight to the altar.

Today's plant

Due to the medical use of the hospital built in the west - meanwhile part of the Hochrhein Clinic with a pharmacy on the ground floor - the building complex is surrounded by driveways and a helipad. The historically incorrect color design sets the building complex apart from the construction of the new hospital building. A square roof turret with two bells and a memorial plaque above the recessed entrance of the former convent wing are intended to commemorate the use of the monastery.

literature

- Romualdus Stockacensis: Monasterium Waldishuttanum . In: Historia provinciae anterioris Austriae fratrum minorum capucinorum . Andreas Stadler, Kempten 1747, p. 232 ff . ( Text archive - Internet Archive ).

- Andreas Fidler, Joseph Wendt von Wendtenthal: Waldshut, but there is only a Kapucin monastery there . In: History of the entire Austrian, secular and monastic clergy beyderley sex . tape 1 . Mathias Andreas Schmidt, Vienna 1780, p. 120 f . ( Text archive - Internet Archive ).

- Vigilius Greiderer: Conventus Waldishutanus . In: Chronica ref. provinciae S. Leopoldi Tyrolensis ex opere Germania Franciscana . Liber I. Typis Joannis Thomae nobilis de Trattnern, Vienna 1781, p. 244 ( archive.org ).

- Johannes Baptista Baur: Contributions to the Chronicle of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province . In: Freiburg Diöcesan Archive . tape 17 . Herder'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Vienna 1885, p. 245–289 ( freidok.uni-freiburg.de [PDF]).

- Johannes Baptista Baur: Contributions to the Chronicle of the Upper Austrian Capuchin Province . In: Freiburg Diöcesan Archive . tape 18 . Herder'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Vienna 1886, p. 153 ( freidok.uni-freiburg.de [PDF]).

- Ernst Adolf Birkenmayer : The former Capuchin monastery . In: Freiburg Diöcesan Archive . tape 21 . Herder'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Freiburg 1890, p. 216–218 ( freidok.uni-freiburg.de [PDF]).

- Lexicon Capuccinum: promptuarium historico-bibliographicum Ordinis Fratrum Minorum Capuccinorum; (1525-1950) . Bibl. Collegii Internat. S. Laurentii Brundusini, Rome 1951.

- Hermann Schmid: The secularization of the monasteries in Baden 1802-1811 . Schober, Überlingen 1980, p. 160 ff .

- Beda Mayer: Waldshut Capuchin Monastery . In: The Capuchin Monasteries of Front Austria (= Helvetia Franciscana ). tape 12 . St. Fidelis-Buchdruckerei, Lucerne 1977, p. 373-381 .

Web links

- Capuchin monastery on monastery-bw

Individual evidence

- ^ Mathaeus Merian: Theatrum Europaeum. Volume 3. Frankfurt am Main 1670, pp. 97 ff.

- ^ Notices from the Historical Association of the Canton of Schwyz. Volume 70, Einsiedler Anzeiger, 1978, p. 47.

- ↑ Vigilius Greiderer: Conventus Waldishutanus in: Chronica ref. provinciae S. Leopoldi Tyrolensis ex opere Germania Franciscana, typis Joannis Thomae nobilis de Trattnern. Vienna 1781, p. 244.

- ^ Ernst Adolf Birkenmayer: The former Capuchin monastery. Freiburg Diöcesan Archive, Volume 21, Freiburg, Herder'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1890, p. 217.

- ↑ Vigilius Greiderer: Conventus Waldishutanus in: Chronica ref. provinciae S. Leopoldi Tyrolensis ex opere Germania Franciscana 1788, typis Joannis Thomae nobilis de Trattnern, 1781. Vienna, p. 241.

- ^ Biografia di San Marco d'Aviano, Attraverso la Germania. P. 33 (online at: documentacatholicaomnia.eu ) (PDF)

- ↑ Statuta Venerable ruralis capituli Waldishutani. Felner, Freiburg 1750.

- ↑ Peter Blickle: The old Europe: from the high Middle Ages to the modern. HC Beck, Munich 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ Petra Rhode In: Heiko Haumann , Hans Schadeck (ed.): History of the city of Freiburg. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, volume. 2, p. 421.

- ^ Beda Mayer: Helvetia Franciscana. Volume 12, Issue 6, 1977, p. 149.

- ^ Johann Müller: The Aargau: its political, legal, cultural and moral history. Volume 2, F. Schulthess, Rupperwyl 1871, p. 210.

- ↑ General church newspaper. Volume 4, Karl Wilhelm Leske, Darmstadt 1825, p. 535.

- ↑ Franz Sebastian Ammann: The evocations of the devil, ghost banners, consecrations and sorcery of the Capuchins. Taken from the Latin Benedictionale and translated, CA Jenni, Bern 1841 (online at: books.google.de )

- ^ Benda Mayer: Helvetia Franciscana. Volume 12, Issue 6, 1977, p. 149.

- ↑ Bernhard Baader: Treasure and Spook in Castle Homberg. In: Folk tales from the state of Baden and the neighboring areas. Herscher'sche Buchhandlung, Karlsruhe 1851, p. 5.

- ↑ Fedele de Zara: Notes storiche, concernenti l'illustre serro di Dio Padre Marco d'Aviano, missionario apostolico. Sim. Occhi, 1798, Volume 2, p. 136.

- ↑ August Baumhauer: The Waldshut church books as historical sources. In: Badische Heimat. Issue 3/4, December 1963, p. 305.

- ^ Ernst Adolf Birkenmayer: The former Capuchin monastery. Freiburg Diöcesan Archive, Volume 21, Freiburg, Herder'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1890, pp. 216–218f.

- ↑ Complete collection of the Grand Ducal Baden government gazettes. Volume 1, point 15 in No. XXXVI of September 2, 1809.

- ↑ Statistical information from Benda Mayer: Helvetia Franciscana. Volume 12, Issue 6, 197,57, p. 157.

- ^ Pocket book Historical Society of the Canton of Aargau. Aarau 1908, p. 200.

- ^ Benda Mayer: Helvetia Franciscana. Volume 12, Issue 6, 1975, p. 143, footnote 75.

- ^ Helvetia Franciscana. Volume 12, Issue 10, p. 320.

- ^ Emil Müller-Ettikon: The Saltpeterer. Schillinger, 1979, p. 275.

- ↑ Tobias Kies: Denied Modernity ?: on the history of the "saltpeter" in the 19th century. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, 2004, p. 244.

- ^ Beat Fidel Zurlauben: Histoire militaire des Suisses au service de la France, Desaint & Saillant. 1703, Volume 7, p. 211.

- ^ Ernst Adolf Birkenmayer: The former Capuchin monastery. Freiburg Diöcesan Archive, Volume 21, Freiburg, Herder'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1890, pp. 217f.

- ^ Fritz Wernli: Building blocks for a story of the Capuchin monastery Laufenburg. Aarau 1911, p. 183.

- ↑ Alexander Theimer: History of the kk seventh Uhlanen regiment archduke Carl Ludwig from its establishment in 1758 to the end of 1868. L. Sommer, 1869, p. 122f.

- ↑ A. Baumhauer: History of the city of Waldshut. H. Zimmermann, Waldshut 1927, 179.

- ↑ Hermann Franz: Studies on the church reform of Joseph II with special consideration of the Breisgau in front of Austria. Herder'sche Verlagshandlung, Freiburg 1908, p. 170.

- ↑ Tobias Kies: Denied Modernity ?: on the history of the "saltpeter" in the 19th century. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, 2004, footnote 212 on p. 110.

- ^ Notes from Father Achilles Beck on the history of the Capuchin Monastery, 1821–1825 General State Archives Karlsruhe, inventory 227 number 271a

- ^ Johann Huber: History of the Zurzach Monastery: A contribution to Swiss church history.

- ↑ Romualdus Stockacensis: Monasterium Waldishuttanum. In: Historia provinciae anterioris Austriae fratrum minorum capucinorum. Andreas Stadler, Kempten 1747, p. 236.

- ^ Catalog of the incunabula in the libraries of the Rottenburg-Stuttgart diocese. Wiesbaden 1993 (incunabula in Baden-Württemberg, inventory catalogs 1), (INKA 14000070) with ownership of the Waldshut Capuchin Monastery (around 1700)

- ^ Joseph Bader: Badenia. I. Volume. Year 1839, p. 43.

- ↑ Paul Schwenke: Journal for Libraries. O. Harrassowitz., 1910, p. 205.

- ↑ a b Library of the abolished Capuchin monastery in Waldshut. Holdings B 750/14 No. 364, in the Freiburg State Archives

- ^ Joseph Bader: Badenia. I. Volume. Year 1839, p. 43.

- ^ Peter Michael Ehrle: From the margraves' zeal for collecting to the state acquisition policy. On the history of the Badische Landesbibliothek. (Lecture given on September 28, 2006 as part of the series of events "200 Years of Baden - Freedom Unites" in Karlsruhe)

- ^ Walther Hümmerich: Capuchin architecture in the Rhenish order provinces: Building regulations of the Capuchins. Self-published by the Society for Middle Rhine Church History, Mainz 1987, p. 8.

- ↑ Argovia. Volume 4, 1864, p. 53, note.

- ^ Hanni Schwab, Roland Ruffieux: History of the Canton of Freiburg. Volume 2, Commission for the Publication of the Freiburg Cantonal History, 1981, p. 698.

- ↑ Romualdus Stockacensis: Monasterium Waldishuttanum. In: Historia provinciae anterioris Austriae fratrum minorum capucinorum. Andreas Stadler, Kempten 1747, p. 237.

- ^ Karl Grunder: Cistercian buildings in Switzerland: new research results on archeology and art history. Volume 1, Verlag der Fachvereine, 1990, p. 253.

- ^ Walther Hümmerich: Capuchin architecture in the Rhenish order provinces. Self-published by the Society for Middle Rhine Church History, Mainz 1987, p. 116.