Tennenbach Monastery

| Tennenbach Cistercian Abbey | |

|---|---|

|

|

| location | Germany Baden-Wuerttemberg |

| Coordinates: | 48 ° 8 '41.6 " N , 7 ° 53' 46" E |

| Serial number according to Janauschek |

361 |

| Patronage | St. Mary |

| founding year | 1158 |

| Year of dissolution / annulment |

1806 |

| Mother monastery |

Frienisberg Monastery later subordinated to Salem Monastery |

|

Daughter monasteries |

no |

The Tennenbach Monastery is a former Cistercian abbey (circa 1158–1806), located near Freiamt and Emmendingen in Baden-Württemberg . After its establishment, Tennenbach developed into one of the most important and largest monasteries in southwest Germany. This is due, on the one hand, to the more than 200 goods that were in the monastery’s possession and, on the other hand, to the large number (672) of relics and saints, which far exceeded the number (374) kept in the mother house.

history

The Cistercian monastery Tennenbach - initially called Porta Coeli ("Heavenly Gate") - was probably founded in 1158. Twelve monks under their abbot Hesso moved from the Bernese monastery of Frienisberg . It is doubtful whether this was done at the instigation of Duke Berthold IV of Zähringen (1152–1186). The Tennenbach families included the lords of Emmendingen , the lords of Hornberg , the lords of Keppenbach and the lords of Üsenberg . A forged founding note in the middle of the 13th century, which was allegedly written in 1161 on the stronghold , names the possession of certain goods and rights in the neighborhood of Tennenbach and lists a list of witnesses, including Duke Berthold and Margrave Hermann III. or IV. von Baden (1130–1160 or 1160–1190). Rights and goods of the Cistercian abbey on the western slope of the Black Forest are already in the privilege of Pope Alexander III. dated August 5, 1178. From a secular point of view, Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa (1152–1190) is said to have chartered Tennenbach, while the removal of monastery property in Neuchâtel due to the founding of the city of the same name by Duke Berthold IV (between 1170 and 1180) is still in the Tennenbacher Goods Book of the 14th century Century aroused protest.

From the end of the 12th century, Tennenbach was subordinate to the Salem Imperial Abbey . Grangien , the monastery owned land, determined the structure of the property, which was concentrated in the Upper Rhine Plain and in the western Black Forest, while the Tennenbacher property in the Baar was largely isolated from it. In the 13th century, the later canonized monk and priest Hugo von Tennenbach († August 20, 1270) worked there: Hugo led a worldly life until he fell seriously ill in 1215. Brought to the Tennenbach Monastery, he recovered contrary to expectations and then entered the monastery as a Cistercian monk. He was exemplary as a monk and priest. Soon after Hugo's death, the people worshiped him.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Margraves of Hachberg held the monastery bailiwick and built their burial place in the Tennenbach monastery . From 1373 the Habsburgs claimed the monastery bailiwick.

In 1444 the Armagnaks devastated the Tennenbach monastery. In 1525 during the Peasants' War it was burned down to the monastery church and was uninhabited for 30 years. In the Thirty Years' War the monks left the convent again. They first moved archives and sacred treasures to the Günterstal monastery in Freiburg and later to Breisach . There they fell in part to Duke Bernhard von Weimar when he conquered Breisach, but the monastery archive and the goods book in Wettingen , Switzerland, were saved. The remote Friedenweiler Abbey was also a place of refuge . In 1723 a fire destroyed most of Tennenbach's buildings. Abbot Leopold Münzer , who came from Freiburg, carried out the reconstruction as a baroque monastery . As part of the secularization of 1806, the Grand Duchy of Baden closed the lucrative monastery. The values adopted amounted to 550,000 guilders .

During the Napoleonic Wars in 1813/14, a military hospital for Austrian and Bavarian soldiers was set up in the former monastery. More than 1,500 soldiers died as a result of injuries and the rampant hospital fever. First they were buried in the former monastery cemetery, later about 1000 in a mass grave in the forest about 800 meters from the monastery. There are now monuments at both grave sites. In 1829 the demolition of the monastery buildings and the auctioning of the stones began.

Buildings and plant

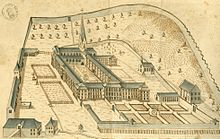

Since the demolition, the structure of the monastery can only be traced from contemporary views and plans. The only remaining remains are the choir of the hospital chapel and a former utility building, today's Gasthaus Engel .

The Romanesque monastery church, based on the model of the Fontenay Abbey , was demolished in 1829/30 and rebuilt as the first Protestant church in Freiburg , the old Ludwigskirche . After they were completely destroyed in 1944, a number of stones were saved and used as spoilers in the new Ludwigskirche from 1952–1954 . Since 2007, other recovered stones have been placed next to the church as souvenirs. The Marien Altar from the Tennenbach Chapel is now in the Augustinian Museum in Freiburg.

The Tennenbacher enclosure was on the south side of the church. The baroque monastery buildings were demolished with the exception of the remains of an economic building and parts of the Gothic sick chapel. The western front clearly shows that this chapel was not free, but connected to a building, the infirmarium . Such a sick bay was available in all Cistercian monasteries. After the Reformation was introduced in Baden (1556), the chapel served as the parish church for around 25 families of craftsmen who were in the service of the monastery until 1836. The construction with Gothic arches shows that the chapel dates from the 13th century. On the western front the inscription In honorem Sanctissimae Virginis Mariae hoc sacellum restauravit A (ntonius Merz) A (bt) Z (ue) T (ennenbach) is engraved into the sandstone. Proof of this can be found in a codex of the Salem Imperial Abbey , which is kept in the Heidelberg University Library . This codex also contains the life story of Hugo von Tennenbach. The author is very likely a Gottfried von Freiburg. He was a clerk and was responsible for drafting documents in Breisgau in the 13th century. After joining the monastery in Tennenbach, he experienced Hugo's death there and wrote his biography as a commissioned work for Abbot Heinrich von Falkenstein.

Gravestones from the 18th century are also embedded in this wall.

According to a report in the Badische Zeitung on May 31, 2012, the exact dimensions of the monastery are to be determined on the 5 hectare site. For this purpose, around 3000 measuring points were staked out on the site in May 2012 and the ground was examined with a ground penetrating radar down to a depth of 2.70 m. With this data, the building structure can be identified, i.e. the location of the buildings, wells, pillars and extensions. One result of the investigation is that a water pipe ran from the monastery mill to the infirmary, which, according to Bertram Jenisch from the monument office, served as a feed pipe for the first water toilet in the area.

The basic structures can be seen from the recordings: The surrounding walls are clearly visible. The church and enclosure were surrounded by a narrow wall, an area reserved for monks. The publicly accessible outer area was connected to this inner area. The utility wing with numerous outbuildings is also clearly visible.

See also

- List of Abbots from Tennenbach

- Tennenbach Altar , late Gothic work of art from the monastery

literature

- J. Alzog: Conrad Burger's rice booklet (Itinerarium or Raisbüchlein of Father Conrad Burger, conventual of the Cistercian monastery Thennenbach and confessor in the women's monastery Wonnenthal 1641–1678). On the history of the Tennenbach Monastery during the Thirty Years War, reprint from 1870/71 Freiburg Echo Verlag, ISBN 3-86028-074-0 Original is in the armarium of the Cistercian monastery Wettingen-Mehrerau, reprint from the Freiburg Diocesan Archive Volume 5/6 1870/71 .

- Michael Buhlmann: The Tennenbacher Güterstreit (= sources on the medieval history of St. George, Part VII = Vertex Alemanniae, H. 12). St. Georgen 2004

- Immo Eberl: The Cistercians. History of a European Order. Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-7995-0103-7 .

- Martin Flashar , Rainer Humbach: Stone on stone. Architectural parts of the old Ludwigskirche are returning. Edited by the Evangelical Community Association of the Ludwig Church Freiburg e. V., Freiburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-923288-57-1 .

- Karl Günther and Christian Stahmann: The monk Hugo von Tennenbach. On the trail of an almost forgotten Cistercian from northern Breisgau, in: s'Eige zeige, Jahrbuch des Landkreis Emmendingen, 25/2011, Emmendingen 2010, pp. 17–72.

- Eduard Heyck: History of the dukes of Zähringen. 1891, reprint Aalen 1980

- Eduard Heyck: documents, seals and coats of arms of the dukes of Zähringen. Freiburg i.Br. 1892

- Rainer Humbach: From Tennenbach to Freiburg - the first building of the Ludwigskirche. In: Freiburger Diözesan-Archiv 115 (1995), pp. 279-314.

- Ludwig Köllhofer: The Abbots of Tennenbach. a contribution to the Emmendinger kath. Parish sheet of St Boniface.

- Franz Xaver Kraus: The art monuments of the districts of Breisach, Emmendingen, Ettenheim, Freiburg (Land), Neustadt, Staufen and Waldkirch (= The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden, sixth volume. District of Freiburg) , Tübingen and Leipzig 1904; here: Tennenbach, pp. 230–237.

- Albert Krieger: Regesta of the Margraves of Baden from 1453 - 1475. Innsbruck 1915; therein documents to the monastery Thennenbach.

- Ernst-Friedrich Majer-Kym: The buildings of the Cistercienser Abbey Tennenbach. Freiburg i. Br., Univ., Diss., 1922.

- Father Gallus Mezler, monachus Sanct Galli OSB .: The Abbots of Thennenbach and St. Georgen. Under: Monumenta historico-chronologica monastica in: Freiburg Diocesan Archive, Volume 15, 1882, 225–246. (Findmittel UB Freiburg i.Br.: Z-Gl. 440) published by JG Mayer, pastor in Oberurnen.

- A. Mezger: Thennenbach. Published in the magazine of the Breisgau history association "Schau-ins-Land" , Vol. 3, 1876; approx. 50 pages.

- Helmut Maurer: The Tennenbacher founding note. In: Schau-ins-Land 90 (1972), pp. 205-211.

- Josef Michael Moser: The end of the Tennenbach monastery. Verlag Kesselring, Emmendingen, 1981, 72 pages

- Stefan Schmidt: The choir stalls of Marienau and the history of the abbey a contribution to the history of the Cistercian Abbey Thennenbach during the Peasant War p. 20 ff. Published in 2004 by the author, copy in the Breisach am Rhein city archive.

- Anton Schneider: The former Cistercian Abbey Tennenbach Porta Coeli in Breisgau. Woerishofen 1904

- Berent Schwineköper: The Cistercian monastery Tennenbach and the dukes of Zähringen. A contribution to the founding and early history of the monastery. In: Heinrich Lehmann (Ed.): Research and preservation. The Etztäler Heimatmuseum in Waldkirch. Cultural and regional historical contributions to the Etztal and the Breisgau, Waldkirch 1983, ISBN 3-87885-090-5 , pp. 95–157.

- Christian Stahmann: "You also have to list ..." On the history of the altars and relics in the Tennenbach Monastery, in: s´Eige show, Yearbook of the District of Emmendingen, 31/2017, Emmendingen 2016, pp. 9–46.

- Max Weber : The Tennenbacher property in the Villingen area. In: Wolfgang Müller (ed.): Villingen and the Westbaar (= publications of the Alemannic Institute Freiburg i.Br., Volume 32), Bühl 1972, pp. 175–191.

- Max Weber; Günther Haselier. u. a. (Ed.): The Tennenbacher Güterbuch (1317–1341). (= Publications of the Commission for Historical Regional Studies in Baden-Württemberg: Series A, Sources; Volume 19), Stuttgart 1969

- Paul Zinsmaier : On the founding history of Tennenbach and Wonnental. In: Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins 98 (1950), pp. 470–479.

-

Badische Zeitung - BZ series 850 years of Tennenbach Monastery :

- The Black Madonna ( Memento from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther, February 26, 2011

- A castle built like the monastery ( Memento from January 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther (vacr), March 19, 2011

- A bell tells its story ( memento from April 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther, April 2, 2011

- The old church registers are real treasures ( memento from April 30, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther, April 23, 2011

- After the heyday came the end of the monastery ( memento from May 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther (vacr), April 30, 2011

- "Gate and heart are open" ( Memento from April 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther, May 13, 2011

- Chests are not that practical after all ( memento from April 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther, March 24, 2012

- The last person to be baptized was Theresia Obergfell ( memento from December 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive ), Hans-Jürgen Günther, April 14, 2012

- The Gate of Heaven ( Memento from May 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Christian Stahmann, May 14, 2011

- Key historical data: Von Glanz und Gloria ( Memento from January 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Prof. Werner Rösener , May 14, 2011

- Researchers want to provide facts: How big was the Tennenbach Monastery? ( Memento of April 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Gerhard Walser, May 31, 2012, accessed June 1, 2012

- Soil reveals secrets ( memento from September 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Gerhard Walser, June 1, 2012, accessed June 2, 2012

Web links

- Tennenbacher Kapelle on the homepage of the Catholic parish Emmendingen-Teningen

- Tennenbach Cistercian Abbey in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

- Tennenbach at Cistopedia

- 850 years of Tennenbach Monastery - Festschrift for the founding anniversary (PDF file; 675 kB)

- The threat to the monastery chapel from a planned road expansion

- Manuscripts of provenance Tennenbach on the website of the Badische Landesbibliothek

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Gerhard Walser: Researchers want to provide facts: How big was the Tennenbach Monastery? ( Memento from April 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Badische Zeitung. May 31, 2012, accessed June 1, 2012.

- ↑ 850 years of the Tennenbach Cistercian Monastery. Aspects of its history from foundation (1161) to secularization (1806). Conference flyer of the Colloquium of the Department of Regional History of the History Department of the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, the Department of Medieval Times of the Department of History of the Justus Liebig University of Gießen and the City of Emmendingen

- ↑ a b Christian Stahmann: The gate of heaven. ( Memento from May 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Badische Zeitung. May 14, 2011.

- ^ Tennenbach: coat of arms. In: cistopedia.org. Retrieved February 13, 2017 .

- ↑ Armin Kohnle : A short history of the margraviate of Baden . 1st edition. Braun Buchverlag, Karlsruhe 2009, ISBN 978-3-7650-8346-4 , p. 62-63 .

- ↑ J. Alzog: Reisbüchlein des Conrad Burger (Itinerarium or Raisbüchlein of Father Conrad Burger, Conventual of the Cistercian monastery Thennenbach and confessor in the women's monastery Wonnenthal 1641–1678) On the history of the Tennenbach monastery in the Thirty Years War. Reprint from 1870/71 Freiburg Echo Verlag.

- ↑ Werner Rösener : Historical key data: Of gloss and glory. ( Memento from January 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Badische Zeitung. May 14, 2011.

- ^ Franz Xaver Kraus : The art monuments of the districts of Breisach, Emmendingen, Ettenheim, Freiburg (Land), Neustadt, Staufen and Waldkirch (= The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden, sixth volume. District of Freiburg. ) Tübingen and Leipzig 1904; here: Tennenbach , pp 230 - 237 on Wikisource.

- ↑ The last person to be baptized was Theresia Obergfell. ( Memento from December 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) In: Badische Zeitung. Hans-Jürgen Günther, April 14, 2012, accessed April 14, 2012.

- ↑ In honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Antonius Merz, Abbot of Tennenbach, renovated this chapel.

- ↑ Gerhard Walser: Soil reveals secrets. ( Memento from September 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Badische Zeitung. June 1, 2012, accessed June 2, 2012.