Blanche of Lancaster

Blanche of Lancaster , Duchess of Lancaster , Countess of Derby , actually Blanche Plantagenet , (German: Blanka von Lancaster ; * probably March 25, 1341 or 1345 ; † probably September 12, 1368 at Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire ) was the daughter and later sole heir by Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster . She achieved historical importance as the first wife of John of Gaunt , whom she helped to gain wealth, influence and titles through her inheritance. Their son, Henry IV, was the first king of the House of Lancaster to ascend to the English throne.

The Book of the Duchess ("The Duchess's Book") was the first own work of the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (approx. 1343-1400) and was probably written as a lament for Blanche after her death. In the poem, the beautiful and virtuous Lady "White" is mourned, which Blanche of Lancaster is said to be based on.

Sources

There are few sources on Blanche, as she died very young and at that time women's affairs were officially run by men. Therefore, if at all, her name appears mostly in connection with her father or husband. So when it comes to Blanche's life, you have to rely largely on guesswork. However, some conclusions can be drawn from the biography of her husband John of Gaunt.

In fact - with one exception - there is no evidence that dates before 1359, i.e. her marriage to Gaunt. Most sources on Blanche's life deal with her marriage and death, or are in some way related to her property or to religious and charitable issues. Since no contemporary portraits and representations of Blanche have survived, only vague descriptions of their appearance and character can be found in Chaucer's Book of the Duchess . These should be viewed with caution, however, as the Lady “White”, who supposedly resembles Blanche, is merely a fictional figure and exaggeration and idealization were important stylistic devices of the poetry of the time.

Origin and youth of Blanche

Blanche was born the youngest daughter of Henry of Grosmont and Isabel de Beaumont. Her father belonged to the English royal family and was a close friend and confidante of Edward III . Along with the King and Prince of Wales, he was one of the wealthiest and most influential men in England. During the Hundred Years War he distinguished himself through military success and was raised to Duke of Lancaster in 1351 . Blanche and her older sister Maud were the joint heirs of his property, as the duke had no other children.

Regarding the exact date of birth of Blanche there is no clear evidence, but Marjorie Anderson assumes in her essay from 1948 on the basis of some of the different ages she discovered that Blanche was probably born between 1340 and 1342. Linda Ann Loschiavo proved in 1978, however, that two of the earliest recorded dates of Blanche's life, namely her marriage in 1359 and the receipt of her inheritance when her father died in 1361, can be used as fixed points to determine the year of birth, which theoretically means the year 1347 itself would still be an option. Accordingly, at the time of their wedding, Blanche would have been at the age of twelve, which was acceptable for the time, and would also have been of legal age and inheritance rights two years later when her father died - at the age of fourteen.

In current genealogical works, the date of birth is usually 25 March and the year of birth is either 1341 or 1345. Probably 1347 would actually be the latest possible year for Blanche's birth, since the first verifiable document of her life is dated May 3rd of the same year. This is a contract that arranged a future marriage between Blanche and John de Segrave, which however never came about. Instead, it was decided to marry her to John of Gaunt , the third eldest son of Edward III.

Blanche's marriage to John of Gaunt

Relationship between Blanche and John of Gaunt

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The marriage, arranged between Blanche of Lancaster and John of Gaunt, allowed Edward to give his son access to part of England's greatest inheritance while strengthening ties with the family of his wife, Philippa of Hainaut , da Maud, the sister von Blanche, with Wilhelm III. von Hainaut was married. Due to the family relationships between the bride and groom, Edward III. before the marriage first Pope Innocent VI. request a dispensation . Since the two were only 3rd cousins and thus only distant blood relatives, this was granted in January 1359.

The wedding between Blanche and nineteen-year-old John of Gaunt, Earl of Richmond , finally took place on Sunday, May 19, 1359 at Reading Abbey , Berkshire, as evidenced by the following chronicle entry:

- Anno millesimo trecentesimo quinquagesimo nono,

quarto decimo Kalendas Junii, Dominus Johannes

de Gaunt, filius Regis Edwardi, Comes Richemond,

Blanchiam, filiam Domini Henrici, Ducis Lankastriae,

consanguineam suam de dispensatione Curiae, apud

Radinggum, duxit uxorem.

- Anno millesimo trecentesimo quinquagesimo nono,

According to various sources, the ceremony was performed either by Thomas de Chynham or, according to John Capgrave , a 15th century author, by the Bishop of Salisbury. King Edward III and his family made precious wedding gifts in the form of jewelry and tableware for the new Countess of Richmond on May 20, while Gaunt presented his wife with a precious jewel and a gold diamond ring at the wedding.

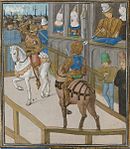

For the entertainment of the guests, numerous tournaments in honor of the bride were held during the wedding celebrations . The first tournaments took place in Reading, followed by many others on the couple's trip to London , where, according to tradition, the most elaborate tournament was held one week after the marriage. The kings of France and Scotland were also present at this outstanding event, which was to serve as a demonstration of the good relations between the king and the citizens of London. Although not trained to fight, the mayor and some of the sheriffs and councilors of London announced their participation in the tournament. They also pledged to hold the field against all challengers during the three days of appeal , which they succeeded in doing. It turned out, however, after their victory that it was not the city leaders who had fought under the coat of arms of London, but that, much to the delight of the citizens, the king and his four sons Edward , Lionel , John and Edmund and nineteen other nobles had successfully honored the city had defended. This tournament was later probably called the merchant's fair at court and was the climax of the glamorous wedding celebrations.

Blanche as Duchess of Lancaster

The Lancaster legacy

With the death of Blanche's father, Henry of Grosmont, by the plague on March 23, 1361, the title of Duke of Lancaster became extinct . His baronies probably fell into limbo , while the earl dignity, presumably according to the law of inheritance at the time, passed to his two daughters and joint heirs, who had to divide them up among themselves. In July 1361, arrangements were made by mutual agreement regarding the division of the property of the late Duke of Lancaster: According to this, Maud received mainly lands in the west of England, namely in Gloucestershire , Herefordshire , Leicestershire and the Welsh Marches and the title of Countess of Leicester . While most of Blanche's legacy was north of the River Trent in Lancashire , Nottinghamshire , Staffordshire and Cheshire , and also included the Earls of Derby and Lancaster. Blanche presumably received the title of Countess of Derby .

Maud had returned to England after the death of her father, where she died completely unexpectedly and without children on April 10, 1362, probably also of the plague. She left Blanche - in accordance with the law of succession at the time - her half of her father's inheritance, including the Earl of Leicester. From this point onwards, Blanche and her husband Gaunt owned the extensive estates of the late first Duke of Lancaster. Like his father-in-law before, John of Gaunt was accordingly also on November 13, 1362 in a parliamentary session in Westminster of Edward III. appointed Duke of Lancaster . Through the inheritance of his wife and new Duchess of Lancaster, Gaunt rose to become one of the most powerful and influential men in England.

The ducal residences

In which residences Blanche stayed throughout her life, it is difficult to understand, as only a few sources are available. More information has been passed down from her husband in this regard: As Earl of Richmond, Gaunt initially had his headquarters in Richmond Castle in Yorkshire . Since this was too far from the royal court, Edward III left him. Hertford Castle near London. In 1362 the inheritance, along with the extensive, ducal lands that Gaunt had to visit regularly for administrative purposes, also included numerous castles, palaces and mansions, the majority of which were in central and northern England, but some were also in Wales. The most important among them were Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire , Tutbury Castle in Staffordshire, Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire, Leicester Castle in Leicestershire and the Savoy Palace in London.

Whether and to what extent Blanche regularly accompanied her husband on these trips to his scattered goods can only be guessed at. It can only be established with certainty that she was in Leicester with Gaunt in June 1362 during the tour of the new lands. During this stay, according to some sources, allegations were made that her sister Maud had been poisoned because her sudden death was allegedly too convenient. These rumors, passed down mainly by the chronicler Henry Knighton, were only associated with Gaunt and never with Blanche, who was apparently not to be blamed.

Aside from this visit to Leicester, there is also evidence of their likely whereabouts suggesting that Gaunt, and probably Blanche as well, made frequent visits to Bolingbroke Castle in the early 1360s. What is certain is that this residence, located southeast of Lincoln , plays a special role in Blanche's biography: in Bolingbroke Castle she gave birth to her son Henry , who was also called Henry of Bolingbroke after his birthplace, and according to some sources she also died here. Blanche certainly stayed at the Savoy Palace, which had been in her family since the 13th century and was Gaunt's preferred London residence. The reason for this was certainly that the Savoy was considered "the most beautiful house in England" after the renovation by Blanche's father .

The social and religious life

Since there are no reports of Blanche, unlike Queen Philippa , according to which she accompanied her husband on his campaigns, and she probably had less to do with Gaunt's political activities, one can probably assume that their common social life is the area where she excelled, for example as a hostess. The Savoy certainly served as one of the main stages, where it was perhaps seen and admired by the poets Jean Froissart and Geoffrey Chaucer . After their death, both wrote poems in which they extolled their beauty and virtue. Chaucer's grieving Black Knight from his “Book of the Duchess” praises her qualities with the following words:

|

|

Geoffrey Chaucer could even have been a member of the ducal household for a while, at least there were close ties between him and the House of Lancaster: Chaucer's wife, Philippa Roet , served the duke as maid of honor of Gaunt's second wife, Constance of Castile , while her sister, Catherine Swynford According to a document dated January 24, 1365, she had previously been an ancille , that is, a servant of Blanche. After Blanche's death, Catherine became the tutor of her daughters and the mistress and later third wife of Gaunt. An indication that Chaucer was valued as a poet by the ducal family and that Blanche might even have been one of his early patrons is provided by a note on his early poem An ABC in Speght's 1602 edition of Chaucer's works, which reads as follows:

-

made, as some say, at the request of Blanch, Duchesse of Lancaster, as a praier for her priuat vse,

being a woman in her religion very deuout .

-

made, as some say, at the request of Blanch, Duchesse of Lancaster, as a praier for her priuat vse,

The note also serves as evidence of Blanche's religiosity, for which there are several other sources. Numerous petitions sent by her and Gaunt to the Pope are documented. There are also some inquiries addressed to the King in the interests of others, which could serve as evidence of Blanche's helpfulness towards other people and especially members of her own ducal household.

Offspring of Blanche

Blanche of Lancaster believed to have seven children, but only three of them reached adulthood. Their first child was a daughter who was born on March 31, 1360 in Leicester Castle and was baptized Philippa like the Queen, whose godchild she was likely to be. At birth Blanche was presumably accompanied by a midwife, whom Gaunt referred to in a letter as "Ilote the wise woman" and in the ducal register as "our well-beloved Elyot the midwife of Leycestre" . After the death of her mother, when Philippa was only eight years old, she was first looked after by Alyne Gerberge, the wife of a ducal squire. Catherine Swynford is later named as tutor for her and her younger sister Elizabeth, who has been shown to have held this post in July 1376 and still in 1380/81. Philippa of Lancaster was only married to João I. de Aviz at the age of 26 and then became Queen of Portugal . This closed in February 1387 marriage was arranged by John of Gaunt, the year before the Treaty of Windsor received Anglo-Portuguese alliance against that of France supported Castile to seal final.

- Philippa of Lancaster (1360–1415), Queen of Portugal

- ⚭ 1387: João I de Aviz (1357–1433), King of Portugal

- Blanca de Aviz (* 1378)

- Beatrice de Aviz (approx. 1386–1447)

- Blanca de Aviz (1388-1389)

- Alfonso de Aviz (1390-1400)

- Duarte I. de Aviz (1391–1438), King of Portugal from 1433–1438

- Pedro de Aviz (1392–1449), Duke of Coimbra

- Henrique de Aviz (1394–1460), Duke of Viseu

- Isabel de Aviz (1397–1471), Duchess of Burgundy

- Blanca (* 1398)

- João de Aviz (1400–1442), Duke of Aveiro

- Ferdinando de Aviz (1402–1443), Grand Master of the Avizordens

- ⚭ 1387: João I de Aviz (1357–1433), King of Portugal

According to various sources, Elisabeth, the second daughter of Blanche and Gaunt, was born either in 1364 or before February 21, 1362/63 in Burford, Shropshire. Unlike her older sister, she was married to the then eight-year-old John Hastings, 3rd Earl of Pembroke , in Kenilworth Castle in 1380 , probably to secure his inheritance for the House of Lancaster.

The young bride, however, did not consent to this marriage, so that it was annulled in 1383, even before her first husband was old enough to consummate it. Instead, she fell to John Holland, 1st Duke of Exeter , the tournament hero and half-brother of Richard II , whom she married in 1386. Shortly after his lynching, Elisabeth entered into her third and final marriage in 1400, this time with the socially lower but also famous tournament fighter, Sir John Cornwall.

-

- Elizabeth Plantagenet, Duchess of Exeter (1364? –1426)

- ⚭ 1380 (canceled after 1383): John Hastings, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1372–1389)

- ⚭ 1386: John Holland, Earl of Huntingdon (approx. 1352–1400)

- Constance Holland (1387–1437)

- Alice Holland (approx. 1392–1406)

- Richard Holland († 1400)

- John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter (1395–1447)

- Edward Holland (ca.1399 - after 1413)

- ⚭ before December 1400: John Cornwall, 1st Baron of Fanhope (before 1390–1443)

- Constance Cornwall († before 1429)

- John Cornwal, 2nd Baron of Fanhopel (1404–1421)

-

Blanche probably gave birth to a total of four sons, three of whom, however, died early and were buried in St. Mary's Church in Leicester and whose dates cannot be precisely determined. Two of their sons are believed to have been named John, one born between 1362 and 1364 and the other before May 4, 1366, while a third son named Edward was born in either 1364 or 1365. The only thing that can be said with certainty about their only surviving son, Henry, is that he saw the light of day at Bolingbroke Castle, while the exact date has not been recorded. Most often, however, you will find information that settles his birth in April or May of the year 1366 or 1367.

Henry Bolingbroke removed his cousin Richard II from the throne in 1399 and was then crowned King of England as Henry IV . He was the first of three English kings from the House of Lancaster, which later fought to keep power in the so-called Wars of the Roses .

- Henry Bolingbroke, 2nd Duke of Lancaster (1366–1413), from 1399 Henry IV of England

- ⚭1380: Mary de Bohun (approx. 1369–1394) ( Bohun House )

- Edward Plantagenet (* and † 1382)

- Henry Plantagenet (1387–1422), from 1413 Henry V of England

- Thomas of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Clarence (1388-1420 / 21)

- John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford (1389-1435)

- Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390-1447)

- Blanche Plantagenet (1392–1409), Electress of the Palatinate

- Philippa Plantagenet (1394–1430), Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden

- ⚭1403: Joan of Navarre (approx. 1370–1437)

- ⚭1380: Mary de Bohun (approx. 1369–1394) ( Bohun House )

Blanche presumably gave birth to a last child before her early death in 1368, a daughter named Isabel, who probably also died in infancy.

Death and memory of Blanche

It was generally believed that Blanche died on September 12, 1369 at Bolingbroke Castle. Since Queen Philippa also died of the plague in the same year, Blanche was ascribed the same cause of death. Newer ones, from Dr. Findings published by John Palmer in 1973/74, however, indicate 1368 as the year of her death, so that current works mostly fluctuate between these two dates. Since it is assumed that Blanche gave birth to a child in 1368, which according to some statements was a daughter and according to others a son, there is speculation that she could also have died giving birth to her last child. At least there is agreement on September 12th as the date of her death, as there is evidence that a mass was held in her memory every year on this day.

John of Gaunt's tomb in St Paul's Cathedral

Blanche was buried in the old St Paul's Cathedral, which was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 . John of Gaunt had a splendid alabaster monument erected for her in the north arcades of the choir next to the main altar and next to it his own altar with a missal, sacrament chalice and chasuble, at which, according to documents from 1372, two clergymen were paid to take masses for the soul to sing of Blanche. The tomb was lavishly expanded in the period that followed and was supplemented in 1374 with portraits of the deceased made of alabaster, in 1379 with a decorative fence and in 1380 with extensive painting. The reputation of the magnificent monument even reached abroad, so that a monk from St. Denis announced that the deceased was "in sepultura incomparabili" (in an incomparable tomb).

After her passing, Gaunt also ordered that a memorial service be held in honor of Blanche every year on the anniversary of her death on September 12th. This custom, common in the Middle Ages, became an important event in the liturgical calendar of the House of Lancaster and was carried on by their son Henry IV after the death of his father. Gaunt appears to have personally attended the festivities for the first time in 1374, as he had not been in England in previous years. From the same year, we have also received records of the expenses for the memorial service, so that one can get an approximate picture of their design. They mainly consisted of the solemn high mass in the black-draped St Paul's Cathedral, at which the grave was surrounded by 24 poor men who held torches and wore cloaks and hoods in white and blue, the colors of the House of Lancaster. In addition, alms were later distributed to the poor and various meals were served for the guests.

In his last will, Gaunt ordered that he be buried in St Paul's Cathedral near the main altar next to his much-loved Blanche:

- “En primes jeo devise… mon corps a estre ensevelez en l'eglise cathedrale de Seint Poule de Londres,

pres de l'autier principale de mesme l'eglise, juxte ma treschère jadys compaigne Blanchilloq's enterre.”

- “En primes jeo devise… mon corps a estre ensevelez en l'eglise cathedrale de Seint Poule de Londres,

The grave monument of the two was either in the reign of Edward VI. (1547–1553) or destroyed by Elizabeth I (1558–1603) and is only known to posterity through the often reproduced engraving from William Dugdale's History of St Paul's Cathedral from 1658.

Geoffrey Chaucer's "The Book of the Duchess"

In the literature it is generally assumed that Geoffrey Chaucer's first own work is a lament for Blanche of Lancaster and was therefore written sometime after her death. There are two sources as evidence for this assumption: On the one hand the prologue to “The Legend of Good Women”, in which a poem called the Deth of Blaunche the Duchesse is mentioned, and on the other hand the retraction in the Canterbury Tales where the book is among other things of the Duchesse is listed. Presumably both works are the same poem, which is why it is traditionally known under the title “The Book of the Duchess” (The Duchess's Book) . In the 1532 edition of Chaucer's works published by Thynne , in which “The Book of the Duchess” appeared for the first time in print, it is, however, entitled The Dreame of Chaucer .

This title is quite fitting, as the poem is about a sleepless poet who, one night after reading the story of Ceys and Alcyone, miraculously fell asleep and had such an extraordinary dream that he wrote it down and presented it to his audience. In the dream, the poet meets the Black Knight during the hunt , who mourns the death of his beloved Lady “White” , whose beauty and virtues he describes with great admiration.

|

|

In lines 1318/19 and a few other passages of the poem there are some of the puns that were quite common in the Middle Ages, which refer to the House of Lancaster and especially to Blanche and Gaunt:

|

|

It is generally assumed that the Black Knight symbolically stands for John of Gaunt and the Lady “White” for Blanche of Lancaster, although the fictional characters cannot be completely equated with real people. Rather, they are idealized and glorified, just like their feelings of sadness and love. However, the historical characters could actually have served as the basis for the characters, especially since the portrayal of Lady “White” contains original elements that could well have been borrowed from the real Blanche.

The lady “White” is described in the poem with a tall, straight stature, golden hair, expressive eyes, a beautiful, lively face and an even neck, as well as with broad hips, round breasts, beautiful shoulders, fleshy arms and white hands with red ones Nails. She also has the skills of dancing and singing expected by court ladies, has mastered a musical instrument and has a select and pleasant language. Her character is characterized by a friendly disposition, a high level of self-respect, a lack of malice and reason, straightforwardness and a love of justice, although she is always moderate and tolerant in her views. Chaucer and his Lady “White” drew the perfect portrait of a kind of white-shining female figure, which in everything corresponded to the ideal of the culture of courtly love .

|

|

Jean Froissart's eulogy in “Joli Buisson de Jonece”

Queen Philippa died one year after Blanche's presumed death, whereupon her compatriot and secretary Jean Froissart (approx. 1337-1405) wrote a song of praise to both deceased in his “Joli Buisson de Jonece” 1373. Froissart's grief seems sincere and, like Chaucer, he praises Blanche's good qualities:

|

|

literature

- Norman F. Cantor: The Last Knight - The Twilight of the Middle Ages and the Birth of the Modern Era. Free Press, New York et al. a. 2004, ISBN 0-7432-2688-7

- George Edward Cokayne : The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom - extant, extinct or dormant. St. Catherine Press, London 1910-1959; Reprint: Sutton, Stroud et al. a. 2000, ISBN 0-904387-82-8

- Helen Phillips (Ed.): Chaucer - The Book of the Duchess. In: Durham Medieval Texts. No. 3, 2nd edition, Durham 1993, ISBN 0-9505989-2-5

- Anthony Goodman: John of Gaunt - The Exercise of Princely Power in Fourteenth-Century Europe. Longman, London et al. a. 1992, ISBN 0-582-50218-7

- Norman William Webster: Blanche of Lancaster. Halstead, Driffield 1990, ISBN 0-9516548-0-2

- Linda Ann Loschiavo: The Birth of 'Blanche the Duchesse' - 1340 versus 1347. In: Chaucer Review. Volume 13, 1978, pp. 128-132.

- Marjorie Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster. In: Modern Philology. Volume 45, 1948, pp. 152-159.

- Norman B. Lewis: The Anniversary Service for Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster, September 12th, 1374. In: Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. Volume 21, Manchester University Press 1937, pp. 176-92.

- Jamieson B. Hurry: The marriage of John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster at Reading Abbey. Reading 1914.

Web links

- Blanche of Lancaster at: thePeerage.com .

- Blanche of Lancaster in: Royal and Noble Genealogical Data on the Web .

- Chronicle of the wedding tournaments 1359 with original Latin text and English translation.

- Online text from John Stow's Survey of London with a presumed grave inscription indicating Blanche's death as 1368.

- Bibliography on Blanche of Lancaster and The Book of the Duchess .

- eChaucer Text and modern translation of “The Book of the Duchess” and other works by Chaucer.

- The Book of the Duchess: An Elegy or a Te Deum? by Zacharias P. Thundy.

Individual evidence

- ↑ A contract regarding an arranged marriage with John, son of John de Segrave, is dated May 3, 1347, see: CP, Vol. VII, p. 419.

- ↑ For a general description of the sources, see: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , pp. 152–159.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 152; Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 33; Cantor: The Last Knight , p. 70.

- ↑ a b c Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 152.

- ↑ Loschiavo: The Birth of 'Blanche the Duchesse' - 1340 versus 1347 , pp. 128-132.

- ↑ See for 1345: thePeerage.com and for 1341: Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 33.

- ↑ Quoted from: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 153; German: In the year 1359, 14 days before the calendar of June [19. May], Sir John of Gaunt, son of King Edward, Earl of Richmond, Blanche, daughter of Sir Henry, Duke of Lancaster, married his blood relatives, according to the ecclesiastical dispensation at Reading.

- ↑ Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 34f, the information on the Bishop of Salisbury was taken from a footnote; Date after CP, Vol. VII, p. 411.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 153; Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 35.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 154; CP, Vol. IV, pp. 204/5 and Vol. VII, 410/11; on Blanches title: thePeerage.com and CP, Vol. IV, p. 204.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 154.

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 43.

- ↑ Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 301-308.

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 43; for a more detailed explanation of the rumors, see: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster p. 154.

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 308; for Bolingbroke Castle as Blanches' place of death, see: thePeerage.com .

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 304.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 156.

- ↑ Chaucer: Book of the Duchess , lines 848-854; ed. u. translated v. Gerard NeCastro, original version: eChaucer , translate version: eChaucer .

- ↑ On the connections between Chaucer and Lancaster: Phillips: Chaucer - The Book of the Duchess , p. 5; on Catherine Swynford: Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 50; for a note on the ABC: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 156f. and Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 37.

- ↑ Quoted from: Phillips: Caucer - The Book of the Duchess , p. 5.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , pp. 154f.

- ↑ For the date and place of birth see: thePeerage.com and Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 36.

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 50.

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 321, 363.

- ↑ Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 123,364.

- ↑ See: thePeerage.com and Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ See: Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ See: thePeerage.com and GenCircles .

- ↑ Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 280, 364.

- ↑ See: thePeerage.com and Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ See: thePeerage.com and Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ See: thePeerage.com and Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ For the discussion of Blanche's death see: Phillips: Caucer - The Book of the Duchess , p. 3 (general); Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 157 and thePeerage.com (death of the plague in 1369); Royal Genealogical Data ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. and CP Vol. VII, p. 415 and Vol. XIV, p. 421 (death 1368); Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 46/7 (death 1368 perhaps at birth).

- ↑ For the exact location of the tomb in St Paul's see 'GROUND PLAN OF OLD ST. PAUL'S 'in: Old St. William Benham: Paul's Cathedral, London 1902 .

- ↑ On the description of the tomb: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 157 and Goodman: John of Gaunt , pp. 257f, 361.

- ^ Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 257; detailed description of the commemoration in: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 157.

- ↑ Quoted from: Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 157; German: First of all, I decide ... my body will be buried in the cathedral of Saint Paul in London, near the main altar of my church, right next to my dear wife Blanche.

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , p. 157.

- ↑ Zacharias P. Thundy: The Book of the Duchess: at Elegy or a Te Deum? ( Memento of the original from April 23, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Chaucer: Book of the Duchess , lines 848-854; ed. u. translated v. Gerard NeCastro, original version: eChaucer , translate version: eChaucer .

- ^ Phillips: Chaucer - The Book of the Duchess , p. 4

- ↑ Chaucer: Book of the Duchess , lines 1318/9; ed. u. translated v. Gerard NeCastro: eChaucer .

- ↑ On the origin of the word cf. Lancaster

- ↑ Phillips: Caucer - The Book of the Duchess , p.5

- ↑ Anderson: Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster , pp. 158/9.

- ↑ Chaucer: Book of the Duchess ; Lines 948-851, ed. U. translated v. Gerard NeCastro, original version: eChaucer , translate version: eChaucer .

- ↑ Phillips: Caucer - The Book of the Duchess , p. 4

- ^ Jean Froissart: Le Joli Buisson de Jonece , in: Jean Alexandre Buchon: Poésies de J. Froissart - Extraites de deux manuscrits de la Bibliothèque du Roi et publiées pour la première fois , Paris 1829, p. 334 (lines 241-250) .

- ^ Translation from: Goodman: John of Gaunt , p. 34.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lancaster, Blanche of |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Plantagenet, Blanche |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | first wife of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and mother of Henry IV. |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 25, 1341 or 1345 |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 12, 1368 |

| Place of death | Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire |