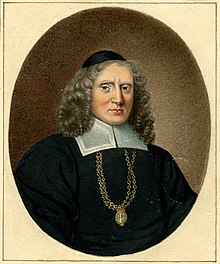

William Dugdale (historian)

Sir William Dugdale (born September 12, 1605 in Shustoke , † February 10, 1686 in Blyth Hall) was an English archaeologist and herald . As a scholar, he was influential in developing medieval history as a research subject.

Life

Dugdale was born in Shustoke near Coleshill Warwickshire , where his father, John Dugdale, was the steward (administrator) of the local landowner. He was educated at the King Henry VIII School in Coventry . In 1623 he married Margaret Huntbach (1607–1681), who bore him 19 children. In 1625, the year after his father's death, he bought Blyth Hall near Shustoke, which would remain his residence for life.

In a dispute over the fencing of his property with a neighbor, he met a few years later on the Leicestershire historian William Burton , who acted as arbiter. He was involved in transcribing documents and collecting church notes, and met other Midlands historians such as Sir Symon Archer and Sir Thomas Habington . He began working with Archer on the history of Warwickshire, and her research led her to the London Public Records Archives, where he met Sir Christopher Hatton , Sir Henry Spelman , Sir Simonds d'Ewes and Sir Edward Dering . Hatton treated him with hospitality and became his main sponsor.

In 1638 Dugdale was appointed by the influence of his friends as Blanch Lyon Pursuivant to an extraordinary Unterherold ( pursuivant of arms extraordinary ), in 1639 promoted to the office of Rouge Croix Pursuivant of Arms in Ordinary . The placement at the College of Arms and the income from his post enabled him to continue his research in London. According to his later report, Sir Christopher Hatton commissioned him in 1641, when he saw the civil war coming and feared the destruction and looting of the churches, with the exact drawing of all the monuments in Westminster Abbey and the most important churches in England.

In June 1642 he and the other heralds were invited to the king in York . When the Civil War broke out, King Charles I commissioned him to move Banbury Castle and Warwick Castle into submission. He witnessed the Battle of Edgehill and later returned with a surveyor to survey the battlefield. He arrived at Oxford with the King in November 1642 and was admitted to the university as a Master of Arts . He worked as a bureaucrat in the royal capital, especially from December 1643 when Hatton was appointed Comptroller of the Household . In 1644 the King made him Chester Herald of Arms in Ordinary .

In his spare time at Oxford he collected material for his books in the Bodleian Library and the university college libraries. During these years he met Elias Ashmole , who later became his son-in-law. After the surrender of Oxford in 1646, Dugdale returned to Blyth Hall. Hatton, who opposed the surrender, went into exile in France, where Dugdale visited him in 1648. He resumed his historical research and worked with Roger Dodsworth at the Monasticon Anglicanum , the first volume of which was published in 1655. The following year he published his own Antiquities of Warwickshire, which was soon recognized as a model for county history. In this work he was one of the first to consider the importance of stone tools and stated that they were "weapons that the British had used before the art of making brass or iron weapons was known".

After the Stuart Restoration , Dugdale became the Norroy King of Arms through the influence of Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon . In this office he took over the heraldic visitation of the counties north of the Trent . In 1677 he received the office of Garter Principal King of Arms , which he held until his death, and was beaten on May 25, 1677 to Knight Bachelor ("Sir"). In his final years he wrote his autobiography at the request of Anthony Wood .

Works

- Monasticon Anglicanum (1655–1673)

- Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656)

- History of St Paul's Cathedral (1658)

- The History of Imbanking and Drayning (1662)

- Origines Juridiciales (1666)

- Baronage of England (1675–1676)

- A Short View of the Late Troubles (1681)

- Ancient Usage of Bearing Arms (1682)

- Visitations of Derbyshire, Yorkshire, etc.

He also edited Henry Spelman's Glossarium Archaiologicum (1664) and Concilia (1664) and added his own extensions. His vita, which he wrote with his diary and his correspondence as well as an index of his manuscript collections until 1678, was edited by William Hamper and published in 1827.

literature

- Jan Broadway: William Dugdale. A Life of the Warwickshire Historian and Herald. 2011.

- Christopher Dyer, Catherine Richardson (Eds.): William Dugdale, Historian, 1605–1686. 2009.

- William Hamper: The Life, Diary and Correspondence of William Dugdale. 1827.

Individual evidence

- ^ Stringer, Homo britannicus. The Incredible Story of Human Life in Britain . London, p. 2

- ^ William Arthur Shaw: The Knights of England. Volume 2, Sherratt and Hughes, London 1906, p. 252.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dugdale, William |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English historian and herald |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 12, 1605 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Shustoke , Warwickshire , England |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 10, 1686 |

| Place of death | Blyth Hall |