Lötschental

The Lötschental ( [ˈløːtʃənˌtaːl] , in local Valais German [ˈleːtʃnˌtalː] Leetschntall ) in Upper Valais is the largest northern tributary of the Rhone in Switzerland . It is traversed by the Lonza River and is located in the Jungfrau-Aletsch-Bietschhorn area of the Bernese Alps , which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site . The Lonza is fed by the Lang glacier , which closes the Lötschental eastward. The valley is surrounded by more than twenty three thousand meter peaks . Around 1500 inhabitants, called Lötscher , live in it. The four communities in the valley are Blatten , Ferden , Kippel and Wiler , which belong to the Westlich Raron district . The Lötschenpass to the north , verifiably already crossed in the Bronze Age, gave the Lötschental an importance as a trade route until the early modern period. Today the valley is best known for car loading for rail transit through the Lötschberg tunnel and as a tourist destination.

geography

The Lötschental, around 27 kilometers long and 150 square kilometers, is located on the southern roof of the Bernese Alps, a sub-group of the Western Alps . The valley can be divided into two sections. The lower section runs from the valley entrance at Gampel ( 634 m above sea level ) in a north-south direction to below Ferden ( 1375 m above sea level ). It has a steep gradient, the outflowing Lonza cuts through the strike surface of the mountain range in a gorge-like narrowed valley. The eastern flank of the valley is dominated by the Hohgleifen ( 3279 m above sea level ), the western valley flank is dominated by the Niwen ( 2769 m above sea level ).

The actual main valley is the upper section running in an east-west direction. It makes up around two thirds of the length of the Lötschental. Starting at Ferden, it ends with the glaciated Lötschenlücke at 3178 meters. The upper Lötschental represents a section of the Alpine Long Valley, which runs from Grimsel over the Konkordiaplatz of the Aletschfirn , the Lötschenlücke and the Ferden Pass to Leuk . The bottom of the Lötschental valley, which rises more flat in the upper section, is around 1000 meters wide. The valley is closed off by the Lang glacier and its main tributary glacier, the Anun glacier. The mountain ranges that run parallel to the north and south of the main valley are part of the Aar massif .

The mountain range bounding to the north forms the Gasterngrat rising from the Lötschenpass to the Hockenhorn ( 3293 m above sea level ) and the Petersgrat to the east. At the same time, it represents the watershed between the Rhone and Aare and thus part of the European watershed . The southern flank forms the Bietschhorn chain with the eponymous Bietschhorn ( 3934 m above sea level ). It separates the Lötschental from the Rhone Valley and is on average a few hundred meters higher than the northern boundary of the valley.

The Lötschental was glacially shaped in the Pleistocene and in its upper part also during the Little Ice Age . The glacial character of the Pleistocene can still be seen today in the valley relief, a trough with trough shoulders on the northern slope.

The southern flank of the valley rises with an average gradient of 40 degrees and is cut through by numerous cantilevers . The streams run off in small erosion channels and are fed by several slope glaciers, including Nest and Birch glaciers on the Bietschhorn. The removed sediments have been deposited in extensive debris walls since the Holocene , when the retreating glacier released large parts of the valley floor. Additionally filled with scree, these natural barriers force the Lonza against the opposite slope and lead to increased erosion there, especially above leaves.

The south side, turned away from the sun, is traditionally hardly populated. The coniferous forest that predominates here is interrupted by some barren sheep pastures and rugged creek cuts. The mountain range above is dominated by the Bietschhorn, on the north-western slope of which there are Nest and Bietsch glaciers. The Breithorn ( 3785 m above sea level ) rises to the east , before the ridge runs out towards Lötschenlücke. To the west of the Bietschhorn are the Wilerhorn ( 3307 m above sea level ) and the Hohgleifen, which closes the ridge in a westerly direction.

The northern flank of the valley has an average gradient of 35 degrees. Initially rising rapidly from the bottom of the valley, it flattens out between 1,800 and 2,200 meters and forms a gallery that now rises more gently and runs in different shapes over the entire flank. This flattening represents the edge of the glacial channel of the glacier that advanced in the Pleistocene. Then the profile of the slope rises again to the Gasterngrat and the Petersgrat to the east ( 3205 m above sea level ). Whose southern slope is home to the Valley of the visible Üsser valley glaciers and the setting glaciers . The Kanderfirn covers the northern slope and drains into the Kander in the Bernese Oberland.

The northern flank is overgrown with partly dense coniferous forest up to around 2000 meters, which is interrupted by deep valley cuts of the flowing streams. Above the tree line, alpine meadows rise gently, in which all the larger Alps of the valley are located.

geology

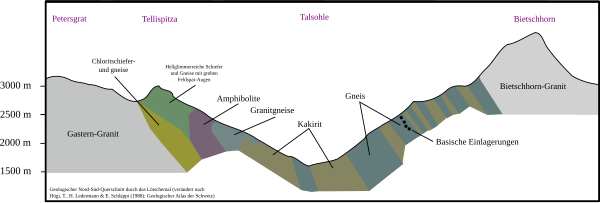

The lower section of the Lötschental belongs geologically to the Rhone Valley and has the structures of the Helvetic nappes on its western slope . The main valley has an asymmetrical cross section, due to tectonic shifts during the alpine mountain formation. The foliation in the Lötschental runs parallel to the two mountain ranges.

The northern slope is lowered by the lower Hercynian shale and is less subdivided due to the lower level of folding. The summit areas of the Gasterngrat, Hockenhorn and the glacier-covered Petersgrats consist of Hercynian Gastern granite, a light, medium-grain biotite granite and granodiorite . The flat shape of the ridge enables the formation of massive glaciations, especially on the Petersgrat.

The steeper southern slope and the valley floor consist of folds of gneiss and kakirite , the summit areas of the Bietschhorn chain of Hercynian Bietschhorn granite, a light, medium to coarse-grained biotite granite.

Glaciers and terminal moraine landscape

Below the Anun Glacier, the upper part of the Lötschental has the characteristics of a terminal moraine landscape . During the Little Ice Age, the recent glacier pushed up a moraine wall measuring around 100 meters in altitude near the Fafleralp . The valley behind is bordered by the now exposed lateral moraines of the glacial channel. In addition to numerous boulders , there are some meltwater lakes, including the Guggi and Grundsee lakes.

The entire Lötschental is shaped by its glacial formation during the Pleistocene, but the remains of the glaciations during the Little Ice Age stand out in particular. The protruding moraine walls can be seen in the vicinity of all recent glaciers lining the valley.

The glaciers of the Lötschental cover 13.7 percent of the area (Petersgrat approx. 1,500 hectares of glacier area, another five glaciers in the upper valley, Jäggigletscher, Langgletscher, Anungletscher, Lötschfirn and Distelgletscher with an area of around 1,600 hectares. The glaciers of the shadowy slope cover an area of 800 hectares) and are the key water reservoirs of the valley. They drain into the Lonza or its tributaries, the flow rate of which therefore depends largely on the prevailing temperatures.

climate

The Lötschental is located at the intersection of the humid, western maritime climate of the Northern Alps and the drier Mediterranean climate of the Southern Alps. The microclimate of the valley is determined by the contrast between sunny and shady slopes. The average annual temperature in Ried is 4.7 ° C, the average annual isotherm of the zero degree limit is at about 2200 meters. The average annual amount of precipitation is 1113 millimeters (Ried). The long-term average snowfall time is 138 days, the average snowfall day is November 25th. The closed snow cover lasts until April 9th (Wiler). In the almost 2000 meter high Lauchernalp, the snow-in time lasts 166 days.

Due to its secluded location, delimited by two mountain ranges, the Lötschental is rarely exposed to stronger winds. With the exception of some south-westerly wind currents from the Rhone Valley, the slope winds predominate due to the topography, which vary depending on the time of day.

Almost the entire valley floor of the Lötschental is seriously threatened by avalanches , and houses and streets are repeatedly damaged and destroyed in winter. Above all, the deep erosion channels on the shadowy slope harbor the risk of avalanches, supported by the falling ice masses of the slope glaciers.

Flora and fauna

flora

The alpine flora of the Lötschental can be divided into vegetation levels according to the Pennine altitude level sequence. This is determined by the continental dry climate of the western Alps . The Lötschental is characterized by perennial rock debris, alpine lawn, subalpine conifers and dwarf shrub communities. The high mountain forests occupy a large area. They are mostly made up of larches and spruces.

In the montane level up to about 1500 meters, i.e. the valley floor to about Wiler, green and arable areas predominate. The forest areas make up around 40 percent of the area, the coniferous forest dominates. At the running out of the avalanche runways and stream channels, there are tall herbaceous meadows in their floodplains, and the pioneering green alder and other small shrubs also grow here .

In the lower subalpine level up to 1800 meters there are extensive coniferous forests, predominantly overgrown with spruce and pine , which take up around half of the area. While the southern Schatthang is continuously forested, on the northern Sonnhang there are only forest areas above the villages. The areas of the valley and the sun slope are largely used for agriculture.

In the upper part of the subalpine level up to 2200 meters, the forest gradually recedes until the natural tree line is reached at around 2200 meters. However, the real tree line on the northern flank has largely been lowered to 2000 meters in favor of the alpine meadows. Dwarf shrubs and alpine lawns grow in this area, tall herbaceous meadows dominate the picture. Most of the Alps in the valley and their pastures lie in it. On the southern flank, larch-stone pine forests form the border of the forest at around 2200 meters.

In the alpine level up to 2500 meters, the bare areas increase, rock debris and rocks dominate the picture. There is a snow valley vegetation . Smaller shrubs, mats and alpine lawns grow here , mainly nib grass . Mosses and lichens exist at higher altitudes . The vegetation limit is reached between 2500 and 3000 meters.

fauna

The alpine fauna of the Lötschental largely coincides with that of the rest of the Valais. Mammals in particular can be found in Alpine ibex , chamois , deer , snow mouse and marmots . Rock ptarmigan , alpine stone grouse and black grouse also live there . You will find undisturbed living space in the largely natural alpine areas.

The golden eagle, which is rare in Central Europe, is native to the Lötschental. The lynx and wolf species, which were considered extinct in Valais at the beginning of the 20th century , can also be found again in the Lötschental. While the lynx found its way into the Lötschental thanks to releases in other cantons, wolves have been migrating back to Switzerland from Italy and France on their own since 1995. As part of the “Wolf Project Switzerland”, the Federal Office for the Environment accompanied the re-immigration of wolves in Upper Valais. Small livestock farmers have reservations about the presence of the wolf. Sheep and cattle husbandry dominate livestock husbandry in the Lötschental. Sheep farmers in particular fear for the safety of their animals.

Settlement and infrastructure

There are four independent communities in the Lötschental. Their centers are all in the area of the valley floor of the upper Lötschental, in the rugged lower third of the valley there are only smaller settlements. The lower third of the valley belongs partly to the municipal areas of Gampel and Hohtenn .

Ferden at 1375 meters is the first community at the beginning of the opening valley. It is followed by the main towns of Kippel and Wiler, which are only a few hundred meters apart. All three communities connect to the north bank of the Lonza. In the upper part of the valley there is Blatten.

Before the construction of the 6.2 kilometer long Mittal tunnel to replace the access road through the narrow Lonza valley, the Lötschental was cut off from the outside world for a few days, especially in winter, by debris and avalanches.

Ferden

Ferden lies at the foot of the northern slope of the Hohgleifen, on the northern bank of the Lonza reservoir. It was first mentioned in a document in 1380 as Verdan . The 342 inhabitants (as of 2007) are divided between the main town, the hamlet of Goppenstein and three cultivated Alps. Furthermore, the now uninhabited hamlet Mittal belongs to the municipality. After Blatten, Ferden is the second largest municipality in the valley in terms of area. Ferden once consisted of a collection of courtyards, which over the centuries gathered around the current town center. Therefore, the place received its still existing cluster village structure . In 1956 Ferden broke away from Kippel, the main town in Lötschental, and has been an independent municipality ever since.

Ferden has three Alps north and west of the village. Above Goppenstein lies the Faldumalp at 2037 meters, and the Restialp a few kilometers north ( 2098 meters above sea level ). The Kummenalp ( 2086 m above sea level ) is located in the wide valley cut of the Färdanbach, which bears an old spelling of the village Ferden in its name and flows west of it into the Lonza reservoir . All three Alps are cultivated in summer. Today the traditional huts are mainly used by locals as holiday homes, cattle and alpine farming are only occasionally operated commercially. Although the Alps lie along the Lötschentaler Höhenweg and are well developed for hiking tourists, there are only a few places to stay overnight.

The Ferden reservoir is located southwest of the village . Its dam dams the Lonza over a length of around two kilometers. It dates from 1975 and is designed as a 67 meter high arch dam with a width of the crown of 126 meters; 34,000 cubic meters of concrete were used for the dam. The lake has a volume of 1,890,000 cubic meters, whereby the water level can vary greatly depending on the amount of meltwater.

Goppenstein

To the south in the narrow valley of the Lonza is Goppenstein at 1216 meters. It houses the train station of the Lötschberg line , which is operated by BLS AG . In addition to the train station, there are extensive facilities for loading cars and trucks for rail transfer through the Lötschberg tunnel , the south portal of which is located directly in the village.

At the beginning of the 20th century, well over three thousand workers lived in the small town during the construction work for the railway tunnel, which for a few years became one of the largest settlements in Valais. Today only a few people live in the heavily traffic-loaded hamlet.

Mittal, which is no longer inhabited today, is a small hamlet on the old valley road south of Goppenstein. In the 19th century there were a few mines in which workers from the valley worked. Since the middle of the century, there was a cart path into the Rhone Valley to transport the mine products.

Dump

Kippel ( 1376 m above sea level ) is the traditional capital of the Lötschental. The history of the parish goes back to the year 1233. Until the late 19th century it was the only one in the Lötschental and thus the spiritual center of the four villages. Today 383 people live in Kippel (as of 2007). The only school in the valley has existed in Kippel since 1960, and in 1982 the Lötschentaler Museum was established in the village. In 1923 an avalanche destroyed large parts of Kippel, the partially damaged parish church from 1742 was not restored to its original state until 1977. In addition to traditional Valais block buildings, some hotels from the turn of the century characterize the place.

The Hockenalp, located to the north at 2048 meters, belongs to Kippel and has been accessible by ski lift since the 1950s. At the end of the 1970s, the lift was shut down after the aerial cableway to Lauchernalp started operating in the neighboring village of Wiler.

Wiler

Wiler ( 1,419 m above sea level ) is the most populous municipality in the valley with 538 inhabitants. The place, which still largely consists of traditional Valais buildings, was hit by a serious fire on June 17, 1900, in which large parts of the village were destroyed. Since then, this day has been known as the Red Blessed Sunday .

The Lauchernalp , the Alp of the valley that is best developed for tourism, belongs to Wiler . It can be reached via the only cable car in the Lötschental and is the starting point for many hiking routes.

Leaves

Blatten ( 1540 m above sea level ) is the uppermost and largest community in the Lötschental. In 1898, Blatten was the first valley town to break away from Kippel and has been an independent municipality ever since. In the place mentioned for the first time in 1433 as uffen der Blattun live 311 people today (as of 2007). The uninhabited hamlet of Kühmatt, which has been home to a Baroque pilgrimage chapel since 1654, is east of the main town. Weissenried ( 1706 m above sea level ) on the northern mountain slope, Eisten and Ried, where the first hotel in the valley was built in 1868, also belong to Blatten.

The Fafler, Gletscher and Guggialp are to the east of Blatten. Since 1972 , the valley road has reached the Fafleralp , which is a major tourist attraction and starting point for hikes to the Anungletscher. To the north of Blatten lie the Weritz and Tellialp, not far from which the Schwarzsee is located at an altitude of 1,860 meters.

Alps

In the Lötschental there are numerous Alps assigned to the communities . The Faldum-, the Resti- and the Kummenalp belong to Ferden. The Hockenalp has its valley location in Kippel, the Lauchern is part of the municipality of Wiler. The Weritz, Telli, Fafler, Gletscher and Guggialp lie in the Blatten area.

All of the larger Alps have at least one inn that is open in summer and their own mountain chapel, in which the pastors of the valley parishes hold church services at regular intervals. Most of the alpine huts are now used as holiday homes for locals, but also for non-residents.

Up until the first half of the 20th century, alpine cultivation in the summer months was an essential part of the livelihood of the valley population and determined their work and living habits. From the middle of the century onwards, they increasingly gained in value as tourist hostels and sights, and alpine farming is hardly ever a full-time business.

In the 1950s, the Swiss Boy Scout Association set up a summer camp on the Faldumalp, and at the same time the first drag lift for winter sports to the Hockenalp was built. In the 1970s, the expansion of the Lauchernalp began to become the winter sports center of the valley, and the Wiler-Lauchernalp cable car was put into operation in 1972.

The Fafleralp is a tourist attraction , the only alp in the valley that has been accessible by car and postbus on public roads since 1972 . Its location at the upper end of the Lötschental at the foot of the Anen Glacier attracts numerous day visitors. In addition to a hotel and several restaurants, there is also a campsite on the Alp.

The Lauchernalp and the Kummenalp are on the historical ascent to the Lötschenpass and have a long tradition as hostels and guest camps. The same applies to the Restialp below the Restipass , which leads to Leukerbad .

Lötschenpass

The Lötschenpass is an alpine crossing over the ridge of the Bernese Alps, which connects the Lötschen with the Kandertal. The pass is at 2690 m above sea level. M. , around five kilometers north of Ferden. The traditional ascent route, coming from the south in summer, runs through the lower Lötschental via Goppenstein to Wiler, following the Lonza. In Wiler the main ascent begins first to the Lauchernalp, then to the Lötschenpasshütte and to the top of the pass. You descend via Selden into the Kandertal, then following the Kander via Kandersteg into the Bernese Oberland . In winter the Lötschenpass can be reached with the gondola lift via Hockenhorngrat. The Lötschenpasshütte is manned continuously from mid-January.

Even in prehistoric times, people committed the pass, as is shown by finds from the Bronze and Iron Ages . From Roman times to the Middle Ages, the Lötschenpass was the most important link between the Bernese Oberland and the Valais, along with the Gemmi pass . As a trade route, it was particularly important as an extension of the Simplon route coming from northern Italy to northern Switzerland. The travelers and traders brought modest prosperity to the places on the ascent route.

In 1519 the first hut was built at the top of the mule track . In the 17th century, the Bernese began building a road over the pass. Religious conflicts between Bernese and Valais, however, led to a rift and meant the end of the construction work. Remains of the partially completed road can be seen on the north side of the pass. In the period that followed, the Alpine crossing, which was only accessible on foot, increasingly lost its importance. In the 19th century, the Swiss Army set up a guard post at the top of the pass, which was converted into a new pass hut and gradually expanded after the Second World War.

history

Prehistory and Roman times

Finds from the Bronze and Iron Ages on the Lötschenpass and its ascent via Kippel bear witness to its early importance as a trade route. Excavations of Celtic cremation graves near Kippel indicate pre-Roman settlement. The Celtic Uberians settled in Upper Valais . In the 1st century BC The Romans conquered the area of today's Valais with the Lötschental and made it the Roman province of Vallis Poeninae (at the latest from the administrative reform of Diocletian around 300 AD combined with Alpes Graiae as Alpes Graiae et Poeninae ).

Migration and the Middle Ages

From the 3rd century AD onwards, the Alemannic and Burgundian tribes invaded Gaul, Raetia and the neighboring Valais. In 277, Roman legions defeated the Alemanni at Acaunus (now Saint-Maurice ). The 4th century shaped tactical alliances between the Romans and the Burgundians. Sometimes the Romans went into battle together with the Burgundians against the increasingly invading Alemanni, then there was again battles against the emerging Burgundians. In 435, the Roman general Flavius Aëtius won a decisive victory in Belgica I against the Burgundians. In the following year, their empire was finally destroyed by the Huns and Herulers, allied with the Romans . The surviving Burgundians settled as federates in Savoy and the Valais. After the death of Flavius Aëtius in 454, the Roman rule over the Valais ended, which fell to the Burgundians who now lived here and remained in their possession until 1032. Since the conquest by the Franks in 534, Burgundy was a Franconian empire that continued to exist as the Kingdom of Burgundy after the Franconian division of the empire .

The Alamanni, oppressed by the Franks in southern Germany, increasingly settled in northern Switzerland from the late 6th century onwards and from the 8th century penetrated the Valais via the Gemmi and Lötschen passes. After the fall of Burgundian rule, Upper Valais was rapidly Alemannized in the 11th century. Their settlements have been documented in the Lötschental from the early 11th century ( Giätrich bei Wiler after excavations in 1990). According to tradition, they displaced a people native to the Lötschental, the Schurten , from the fertile settlement areas in the valley. The Schurten had henceforth in the barren mountain forests on the shady side of the valley live (in Obri forest near Wiler remains were discovered of a settlement with those same excavations) and were feared by the Alemanni for their raids. According to another tradition, it was a gang of thieves living in the woods who attacked the villages in the valley.

When the Kingdom of Burgundy perished in 1033 , the Valais became part of the immediate empire and was thus directly subordinate to the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . In the period that followed, the small nobility developed in Valais. The Lötschental came into the possession of the Lords of Turn . In 1233 Gyrold von Turn donated the parish in Kippel, the first and until the 19th century the only parish church in the valley.

The Lords of Turn were entangled in numerous feuds and fought alongside the House of Savoy against the Zähringer , who held the rectorate of Burgundy on behalf of the emperor (1127 to 1218), for supremacy in the Valais. Weakened by countless conflicts and wars, in the 14th century the Valais communities formed the protective alliance of the tens and invoked their imperial immediacy. In 1355 at the latest, the League of Seven Zends was created , which consisted of the places Goms, Brig, Visp, Raron, Leuk (the five upper toes) and Siders and Sitten (lower toes). This drove the Lords of Turn and their Savoyard allies from the Upper Valais and conquered the Lower Valais in the period that followed. From then on they administered themselves and in the 16th century broke away from subordination to the Bishop of Sitten . After the expulsion of the gentlemen von Turn, the Lötschental also became politically dependent on the five upper Valais tens.

Common names for the Lötschental in the Middle Ages were Vallis Lyche (mentioned in a document in 1233), Lyech, Vallis Illiaca and Illiacensis superior .

The Lötschental in modern times

In the 17th century, work began on the Bern side of the Lötschenpass to expand it as a transport route. On behalf of Captain Abraham von Graffenried, the connection, named after him Grafenriedsche Strasse , was supposed to strengthen trade. However, the project failed due to religious disagreements and earlier disputes with the seven tens, who refused to give their consent for the further construction of the pass road in their area. In January 1528 the people of Bern decided to convert to the Reformation by referendum, the Valais remained Catholic. This led to armed conflicts from 1536 after Savoy had lost the Lower Valais to Bern and, in the face of the defeat, allied with the seven tens. When the Bernese were expelled from the Valais, the seven tens occupied the Lower Valais and placed it under their administration.

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the plague raged in Valais. In 1578 and 1627 in particular, the Lötschental was also affected, the entrance to the valley at Gampel being cordoned off by plague guards.

In 1790 the Lötschers bought themselves free of the five upper tens for 10,000 kroner, became imperial direct and in 1795 issued their own constitution. After the defeat of the seven tens by Napoléon in the Battle of Phyn in 1799, the Valais was occupied by French troops. After a few years as a republic, the French incorporated the Valais into the Napoleonic Empire in 1810 as the Département du Simplon . After the fall of Napoléon, Valais declared its independence on March 13, 1814, and in August 1815, after deliberations at the Congress of Vienna, became the 20th canton of Switzerland .

With the beginning of industrialization in the Rhone Valley in the late 19th century, numerous young Lötschers turned their backs on their home valley, and emigration could only be slowed down slowly by the emerging tourism and improved transport connections in the first half of the 20th century. The valley road was built step by step until 1955 and has since connected the Rhone Valley with all the communities in the Lötschental.

During the short period of construction work on the Lötschberg tunnel between 1907 and 1913, the valley flourished economically, with thousands of migrant workers populating the work barracks around Goppenstein. Since the 1950s, the tunnel has been an important transit route between northern Switzerland and the Valais and is accordingly heavily frequented. With the Lötschberg Base Tunnel , however, the connection through the Lötschental is bypassed.

In 1898, Blatten was the first parish to break away from the Kippel Priory, which until then was the capital of the valley and its central administrative seat. 1956 Ferden and Wiler became an independent parish. Since the 1970s, the Lötschental has been increasingly geared towards tourism, especially winter guests.

In 1993, 1996 and 1999 there were major avalanches in the Lötschental. The avalanches in the winter of 1999 damaged or destroyed individual farm buildings, alpine huts and residential buildings on the Gletscheralp and in the hamlet of Ried near Blatten. Since then, further measures have been taken to protect the population as well as communication and traffic connections, including the avalanche protection dams between Kippel and Wiler and the construction and extension of street galleries.

On 13 December 2001, the Jungfrau-Aletsch-Bietschhorn -type region, which includes the southern and eastern parts of the valley, the World Heritage Committee with decision UNESCO in the World Heritage List (UNESCO World Heritage added). Since then, the Anun Glacier and the glacier foreland up to the Fafleralp have been under strict nature protection.

Economy and Supply

Until the early 20th century, the inhabitants of the Lötschental lived almost exclusively from agriculture and livestock, which was mainly done in the summer months through alpine farming. While arable farming largely disappeared, except for a few years of food shortages during World War II, as part of the Wahlen plan , cattle farming is still practiced today.

Most of the pasture and arable land is in the valley and on the sunny slopes of the north flank. Mainly sheep, but also cattle for dairy farming, often the typical Eringer cows in Valais, are kept here . In contrast, the steep southern flank is largely wooded and only offers pasture areas in a few places, mainly for less demanding goats and sheep.

The timber industry represents a sideline , which was also used to supply the population with firewood. Even today, tree-free sections of the slope can still be seen, especially on the northern slope, which were once used to remove the wood.

Until the end of the 19th century, the secluded valley was isolated from the outside world, also because the once busy Lötschenpass had largely lost its importance as a transalpine trade route. The barren existence of the mountain farmers affected all areas of people's life and still shapes the image of the valley today. The people produced their necessities largely on their own and found a meager livelihood by cultivating the mountain pastures, but hunger and misery were not uncommon. In this atmosphere a strict, pious and self-sufficient valley community developed. Again and again, young Loetschers in particular turned their backs on their valley to seek a livelihood in the Rhone Valley. In the 20th century, before the valley road was expanded, the population of the valley began to become increasingly aging.

From the second half of the 19th century, some Lötschers found employment in lead, silver and anthracite mines, which were built in the lower valley near Goppenstein and Mittal by English mining companies. In order to be able to transport the raw materials away, they expanded the previous footpath from Gampel to Goppenstein into a transport route, but the upper valley was still only accessible on foot.

After the first ascent of the Hockenhorn by the Englishman Arthur Thomas Malkin in 1840, British mountaineers in particular began to be interested in the valley. After the construction of the first hotel in Ried in 1868, the Lötschers reluctantly adjusted to the slowly emerging tourism. At the end of the 19th century, several progressive clubs were founded, including a theater and music society in Ferden.

The construction of the Lötschberg tunnel from 1906 to 1913, the south portal of which is near Goppenstein, brought a large number of jobs and foreign workers into the valley for the first time. In addition to Goppenstein, the other places in the valley also benefited from the project. Hotels were founded, the people adjusted to the needs of guest workers and opened up to influences from outside the valley. Since the completion of the tunnel, the Lötschental has had a train connection with the train station in Goppenstein.

Lötscher also increasingly found jobs in factories in the Rhone Valley, where industrialization began in the late 19th century. Lonza AG was founded in Gampel in 1898, initially generating electricity with Lonza water and providing work for a few dozen people in the valley.

After twelve years of construction, a road connection from Gampel to Ferden was put into operation in 1939. The road to Wiler was extended by 1953 and to Blatten by 1954. Thus the valley could be reached by car and postbus from the Rhone valley, the locals had the chance to work as commuters outside the valley. With better transport connections, a stronger focus on tourism began in the second half of the 20th century, which soon created numerous jobs. The valley inhabitants were offered a perspective in their homeland, so that the population decline could be stopped.

The valley road was further expanded from the 1980s and provided with numerous galleries and tunnels so that it can be used all year round. The Mittal Tunnel, built in 1985, bypasses the narrow and steep section of the lower Lötschental between Gampel and Goppenstein and runs 4.2 kilometers through the mountainside of the Hohgleifen between Hohtenn and Goppenstein. In particular, the expansion of the access road to Goppenstein had become necessary due to the high volume of traffic to the local car loading station.

Since 1975, the valley has been largely supplied with the river from the Lonza reservoir, which dams the Lonza over a length of around two kilometers.

tourism

The roots of tourism in the Lötschental lie in the 19th century, when British alpinists discovered the valley for themselves and the first hotels were founded (the first in Ried in 1868). In the following decades, Kippel developed into a popular location for tourist hostels. Some hotels from the turn of the century still exist today. However, the valley, which is difficult to reach, especially in winter, was barely developed for mass tourism until the valley road was expanded in the middle of the 20th century. With the valley road, tourism began to revive; Initially, mainly summer guests came, but this changed with the expansion of winter sports in the 1970s. At that time, the Lauchernalp above Wiler was expanded into a winter sports center. Accessible with the cable car, which was inaugurated in 1972, the ski area offered numerous slopes and newly built lifts. In 2003, the Lauchernalp winter sports area was expanded to include the glacier lift on the Hockenhorngrat at an altitude of 3,111 meters, making it the seventh-highest skiing area in Switzerland (after Zermatt, Saas-Fee, Verbier, St. Moritz, Saas-Grund and Belalp).

The numerous hotels and holiday apartments in the villages of the valley record 150,000 to 200,000 overnight stays annually, two thirds of them in the winter season. There are also two campsites in Kippel and on the Fafleralp .

The Lötschental has around 200 kilometers of developed hiking and mountain trails. The most famous is the Lötschentaler Höhenweg, which connects all the Alps on the north flank and starts at the Lauchernalp cable car station. From Fafleralp, tours over the Anun Glacier are possible.

1994/95 was at the back in the Lötschental at 2355 m above sea level. M. built the Anenhütte with 50 beds. From March to October it was available for mountain and ski tours e.g. B. on the Mittaghorn and over the Lötschenlücke available. On March 3, 2007, an avalanche of dust completely destroyed the hut. In summer 2008, a new and avalanche-proof replacement went into operation, which had been built since September 2007.

population

Around 1500 people live in the Lötschental today. The population of the valley has increased only below average in the last few centuries. Since the 18th century, when around 800 people lived in the valley, the number of inhabitants has only doubled. This is due to the spatial limitation of the valley, famine and a strong migration of young Loetschers. While they mostly hired themselves out as migrant workers and mercenaries in the Middle Ages and early modern times, they were drawn to the work quarters of the Rhone Valley in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Life in the valley was determined by the traditional valley system until the 19th century. In times of self-government, the emissaries of the villages discussed the politics in the valley at meetings in Kippel. If the valley was sheltered by foreign masters, it was mostly ruled by administrators. In addition, the parish in Kippel had a major influence on developments in the valley.

Culture and customs

Valais German , a dialect of the highest Alemannic , is spoken by the inhabitants . In terms of costumes, dialects and customs, numerous differences can be seen even from nearby communities in the Rhone Valley.

In the Lötschental, which has always been secluded, numerous seemingly archaic customs and traditions have been preserved. The annual cultural highlights, in addition to the church festivals, are the alpine pasture and alpine descent .

The memory of events and myths of the past has been preserved in the collective memory of the valley community through an extensive treasure trove of legends, mostly passed down orally, in part up to the present day. In the past, these sagas were mainly used to entertain and educate children in the valley's social community.

Tschäggätta

The Tschäggätta disguises with the associated larvae, which are typical in Lötschental, are originally only worn by single young men and only from 12 p.m. to 7 p.m. during Shrovetide between Candlemas on February 2 and Ash Wednesday . The Tschäggätta cladding consists of animal skins (mostly sheep or goat skins) that cover the whole body, the larger than life, hand-carved and painted larvae (mask) worn in front of the face, with special, hand-made wool (yarn) gloves (also Called Triämhändschn ) and a long stick, which is equipped with bells or noisy objects.

In this elevator , the young people from the four towns attack the neighboring villages. They make noise, frighten the residents and blacken the faces of children with soot (referring to the Christian ash cross on Ash Wednesday). The origin of the custom is unclear, the first records date from the 19th century, when the pastor Prior Gibster in Kippel imposed a fine of 50 cents on the nocturnal activity. Only in two forms of parades do the Tschäggättä come together to form groups, the largest takes place every Shrovetide Saturday in Wiler, the other on Feistn Frontag .

The pagan-Alemannic custom of Tschäggätta (related to the rites of the Alemannic Carnival ) was mixed in the Middle Ages with the Catholic customs of Carnival and Ash Wednesday. There is also a legend that the wild figures were supposed to remind of the raids of the Schurten , supposedly living on the south side, the shadowy side of the valley. A connection with the uprising in 1550, the drinking bull war is suspected; the insurgents would have made themselves unrecognizable with wooden masks.

Lord of God grenadiers

The Herrgottsgrenadiers are traditional festival disguises worn by young men from the established families. At religious and secular festivals, the parade uniforms of the grenadiers , which are usually passed on within the families, are worn. This is a reminder of the Lötscher who left the valley to work as mercenaries . When they returned to their homeland after their service, many wore the parade uniform of their former unit on special occasions. This resulted in a colorful variety of uniforms, as the mercenaries served in different armies. After their death, they bequeathed their uniforms to their sons, who continued to wear them in their place, thus establishing the tradition.

Today the Herrgottsgrenadiers wear uniform uniforms in church processions and secular festivals, similar to the guard associations. Except for church occasions, they march with fantasy flags and to brass music. Today's uniform is based on patterns from the 17th century.

literature

- Hedwig Anneler: Lötschen. Regional and folklore of the Lötschental. Academic bookstore Max Drechsler, 1917 (reprint: Haupt, Bern 1980, ISBN 3-258-02962-8 ).

- Fritz Bachmann-Voegelin: Blatten in the Lötschental. The traditional cultural landscape of a mountain community. Bern 1984, ISBN 3-258-03326-9 .

- Werner Bellwald: Lötschental. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Maurice Chappaz : Lötschental. The wild dignity of a lost valley community. In historical photographs by Albert Nyfeler . Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1979 (reprint: 1990, ISBN 3-518-40254-4 ).

- Susanne Schmidt: The relief-dependent snowpack distribution in the high mountains. A multi-scale method network using the example of the Lötschental (Switzerland). Self-published dissertation, Bonn 2006, ISBN 978-3-931219-37-6 . (Chapter 2 - Study area, pp. 17-29. Description of the topography, geology and climate of the Lötschental).

Web links

- Lötschental on the ETHorama platform

- Web presence of the Lötschentalmuseum in Kippel (some additional information and images)

- Documentaries by Carl Abächerli (1893–1986) about the Lötschental (Swiss television, August 10, 2008)

- Lötschental Tourism website

- Tremendous carnival , report on the Tschäggättä in the Lötschental in Die Zeit from January 31, 2013

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Thomas Mosimann: Investigations into the function of subarctic and alpine geo-ecosystems: Finnmark (Norway) and Swiss Alps. Physiogeographica, Volume 7, Basel 1985, p. 488.

- ^ A b Hans Leibundgut : Forest and economic studies in the Lötschental. Dissertation. Self-published, Zurich 1938.

- ↑ Andreas Wipf: The glaciers of the Bernese, Vaudois and northern Valais Alps: a regional study of glaciation in the periods of 'past' (high level of 1850), 'present' (expansion in 1973) and 'future' (glacier retreat scenarios, 21st century). 1999.

- ↑ Wolfgang Weischet, Wilfried Endlicher: Regional climatology. Part 2: the old world. Stuttgart 2000.

- ↑ a b Bianca Hörsch: Relationship between vegetation and relief in alpine catchment areas of Valais (Switzerland). A multi-scale GIS and remote sensing approach. Bonner Geographische Abhandlungen, Bonn 2003, p. 256 ff.

- ^ Fritz Bachmann-Voegelin: Blatten in the Lötschental. The traditional cultural landscape of a mountain community. Bern 1984.

- ↑ On the other hand, the nasin is eradicated .

- ^ Heinrich Haller: On the ecology of the lynx Lynx lynx in the course of its reintroduction in the Valais Alps. P. Parey Verlag, 1992, pp. 18, 28 and 34.

- ↑ Predator sighted in Lötschental: Wolf kills half a dozen sheep. ( Memento of the original from May 3, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on: 1815.ch (Walliser Bote) of July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Wolf again tears sheep in the Lötschental. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on: 1815.ch (Walliser Bote) of August 29, 2011.

- ↑ Wolf Project Switzerland. In: Swiss Wildlife Biological Information Sheet. Number 4, August 1999 (PDF; 52 kB)

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Wolf information page . of the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN)

- ↑ Schäfer take measures. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on: 1815.ch (Walliser Bote) of July 28, 2011.

- ↑ The expansion of the Lötschentalstrasse. History of the Upper Valais Transport and Tourism Association. on: vov.ch/geschichte

- ↑ Werner Bellwald: Ferden. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Lötschental. In: Structurae

- ↑ Werner Bellwald: Kippel. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Werner Bellwald: Blatten (VS). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Read up at www.loetschenpass.ch/geschichte ( Memento of the original dated August 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Hedwig Anneler: Lötschen. Landes- u. Folklore of the Lötschental.

- ↑ On the ancient finds from the Lötschental: Olivier Paccolat: Kippel and the Lötschental. In: Vallis Poenina. The Valais in Roman times. Exhibition catalog. Walliser Kantonsmuseen, Sitten 1998, ISBN 2-88426-039-0 , pp. 198-200.

- ^ Renata Windler: Franks and Alamanni in a Romanesque country. Settlement and population of northern Switzerland in the 6th and 7th centuries. In: Karl-Heinz Fuchs, Martin Kempa, Rainer Redies, Barbara Theune-Grosskopf, Andre Wais: Die Alamannen . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, pp. 261–268.

- ↑ Loetschentalmuseum.ch ( Memento of the original from September 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Werner Bellwald: Lötschental. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ a b Victor Tissot: La Suisse inconnue. 1888.

- ↑ History of the Anenhütte ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on the website www.anenhhuette.ch

- ^ Linguistic Atlas of German-speaking Switzerland . Volumes I – VIII. Francke, Bern and Basel 1962–1997; Walter Henzen : To weaken the night vowels in High Alemannic. In: Teuthonista 5 (1929) 105–156 (relates to the dialect of the Lötschental); the same: the genitive in today's Wallis. In: Contributions to the history of the German language and literature 56 (1931) 91–138 (concerns the dialect of the Lötschental); the same: the old weak conjugation classes survive in the Lötschental. In: Contributions to the history of the German language and literature 64 (1940) 271–308.

- ^ Maurice Chappaz: Lötschental. The wild dignity of a lost valley community. In historical photographs by Albert Nyfeler. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1979.

- ↑ see web link Unseurable Carnival

- ↑ The Tschäggättä

- ↑ Migros-Genossenschafts-Bund (Ed.): Feste im Alpenraum. Migros-Presse, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-9521210-0-2 , pp. 72-75.

- ↑ Leetschär Fasnacht - the mystical tradition , Walliser Bote , February 15, 2020, p. 6

Coordinates: 46 ° 25 ' N , 7 ° 50' E ; CH1903: 630000 / 140000