Battle of Rocroi

| date | May 19, 1643 |

|---|---|

| place | Rocroi , France |

| output | French victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 23,000 men | 23,000-27,000 men |

Les Avins - Leuven - Tornavento - Guetaria - Fontarrabie - Corbie - Diedenhofen 1639 - Turin - Aire-sur-la-Lys - Honnecourt - Barcelona - Cartagena - Diedenhofen 1643 - Rocroi - Orbetello - Fort Mardyck - Dunkirk - Rethel - Bordeaux - Lens - Arras - Valenciennes - Battle of the Dunes

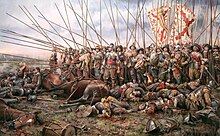

In the Battle of Rocroi on May 19, 1643 , the French and Spanish armies met during the Franco-Spanish War (1635-1659) . The battle ended in a devastating defeat for the Spanish troops.

prehistory

In order to defuse the French pressure on Catalonia and to prevent an invasion of the Free County (Franche-Comté) , the Spanish commander, the governor of the Spanish Netherlands , Duke Francisco de Melo (or Mello), decided to build the French fortress of Rocroi in what is now the French department To attack Ardennes . Melo had not been able to adequately equip his cavalry with horses, as these were too expensive in war-torn Europe and the Spanish coffers were empty.

Most of the soldiers, too, were not up to the rigors of a campaign. In February 1643, the Flanders Army decreed that less fit and smaller men could be recruited to make up for the shortage of recruits. Up to 25 of these less fit soldiers were allowed to serve in one company each. In order to be able to arm them, the smaller arquebuses were reintroduced, which had only been separated out in 1636 and replaced by muskets .

On May 12th, the Spaniards came within sight of this fortress and began preparations for a siege. At the same time, Duke Ludwig von Enghien was entrusted with the supreme command of the French troops in Champagne. He decided to come to the aid of the garrison in Rocroi. With a daring and quick troop maneuver, Enghien was able to position his French army a few kilometers south of the Spanish army. On May 17th, the French were able to increase the garrison in Rocroi by 150 musketeers . On the 18th, the armies took up their position in a plain southwest of Rocroi and began bombarding each other in the afternoon.

Duke Ludwig von Enghien's goal was to force the battle before the arrival of the Spanish supplies under Johann von Beck (around 1000 horsemen and more than 3000 foot soldiers).

Course of the battle

The French had a total of about 22,000 men: 18 battalions of infantry and 32 cavalry companies. 15 of the infantry battalions under Espenan were divided into two lines. The cavalry was arranged in two wings, the left (13 companies) from La Ferté and the right (15 companies) from Enghien and Gassion. The reserve (three battalions and four cavalry companies) was under the command of the Baron de Sirot. In addition, Ludwig von Enghien had 600 to 1000 musketeers posted between the two lines of the infantry battalions.

The Spanish army was about the same size and probably consisted of 19 battalions of infantry. As on the French side, the cavalry was posted in two wings (left and right) on either side of the infantry, which was also arranged in two lines (ten and nine battalions). In addition, it must be mentioned that the Spaniards had developed their own infantry combat formation during the Thirty Years' War: the so-called " Terzio " (or "Tercio"). These troops of musketeers and pikemen, fighting in the square , were able to repel cavalry attacks effectively; The main task of the pikemen was to protect the infantrymen, armed with muskets or the lighter arquebuses , from the enemy's cavalry. In the middle of the Spanish Tercios cannons were set up, which - in the final phase of the battle - shot the unprepared attackers from quickly opened corridors of the defensive front. This gave the Tercios a terrifying power of fire and resistance. This fact should cause a surprise at the end of the battle.

Six Spanish Terzios in reserve formed the core of the Spanish order of battle. In contrast to the German, Walloon and Italian regiments in Spanish service, these were considered elite troops.

On the right it consisted of seven regiments under Isenburg and on the left of twelve under the Duke of Alburquerque . They also had a reserve company under Baron von André. On the night of May 19, de Melo decided to place musketeers in a thicket not far from the left flank in order to be able to defend it better.

The armies of roughly equal strength collided, and Enghien must have been keen to decide the battle before the arrival of Spanish reinforcements. The French commander-in-chief succeeded in decimating the Spanish army, with the loss of around 4,000 to 4,500 soldiers and around 7,500 deaths from the enemy. Among the prominent dead on the Spanish side were the Italian Visconti as commander of the right center and the regimental commander Velandia, both of whom had perished in the battle against Gassion's mounted and Enghien's right wing cavalry. The highest-ranking dead person in the Spanish crown was the Maestre de campo general ( Colonel General ) Paul Bernard de Fontaine , who had even functioned as Gobernador de las Armas (Army Chief) in 1640/41 . The 66-year-old native of Lorraine fell towards the end of the battle when, due to illness, he had been directing the musketeers' fire intervals from a lounger. (The piece of furniture ended up as spoils of war in Paris, where it is now exhibited in the Army Museum belonging to the Hôtel des Invalides .)

The remnants of the Spanish army, which after the flight of the allied troops consisted only of the Spanish Terzios held in reserve, initially refused to honorably surrender ; The 11th Spanish Infantry Regiment initially rejected the offer with the words: "His Excellency seems to have forgotten that he is dealing with a Spanish regiment!" Several French attacks failed before Enghien was forced to face his high losses To achieve cessation of the fight by negotiation.

The last Tercio, because of his good starting position in a small wood, the threatened advancement of the relief army and the high losses of the French in their fight, succeeded in granting them the same conditions as the soldiers when a fortress was surrendered , namely an honorable deduction in arms and with flags. Probably a unique event in the history of the war, the Tercio then moved across France in full gear to its Basque homeland.

After the Spaniards surrendered, French horsemen stuck in the crowd - they probably thought a movement among the Spaniards was the resurgence of resistance - began to cut everything down. Enghien ended this slaughter immediately, partly at the risk of his own life. When he got off his horse, according to eyewitness reports, he was not surrounded by soldiers of his own, but by Spaniards who thanked him on their knees. The fact is that rarely a general was so respected by the troops of the enemy.

On May 19, at 10 a.m., the battle was over. The French had won.

consequences

The Battle of Rocroi gained fame as the worst defeat a Spanish army has ever suffered. It was often referred to as the turning point in history and the end of Spanish supremacy in Europe. In fact, however, the war lasted another 15 years, and although Spain suffered further defeats, it was able to maintain its position in the southern Netherlands. One cannot speak of the decline of a military power or the decline of a branch or group of weapons, because the resistance of the last Tercio, which could not be broken even by gunfire, and the fact that the French Cardinal Retz brought relief to Bordeaux around 1650 with the help of such units , show the perseverance of the Spaniards and their infantry and the tactical strength of the Tercios.

The long-awaited French victory marked the beginning of the “happy six years” of the regent Anna of Austria and her underage son, who later became Louis XIV , before the Fronde again plunged the country into turmoil in 1648/1649 .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Geoffrey Regan: Battles that changed History , London 2002, p. 109

- ↑ Gerrer / Petit / Sanchez Martin 2007 p. 95; the 4,500 men of Beck's reserve army arrived too late and no longer intervened in the battle.

- ^ A b c John Lynch: The Hispanic world in crisis and change 1598–1700 , Oxford 1992, p. 165

- ↑ Geoffrey Parker: The Military Revolution - The Art of War and the Rise of the West 1500–1800 , Frankfurt am Main / New York 1988, p. 86

- ↑ Gerrer / Petit / Sanchez Martin, chap. 12 Controverses au sujet de la capitulation du dernier tercio , pp. 86–91.

- ↑ Gerrer / Petit / Sanchez Martin, Rocroy, p. 77

- ↑ Gerrer / Petit / Sanchez Martin, Rocroy, p. 76

filming

Scenes from the Battle of Rocroi, including the quote from the 11th, can be seen at the end of the film Alatriste by Augustin Diaz Yanez based on Arturo Pérez-Reverte.

literature

- Mark Bannister: Condé in Context - Ideological Change in Seventeenth-Century France , European Humanities Research Center, Oxford 2000. ISBN 1-900755-42-4 .

- Berard Gerrer. Patrice Petit. Juán Luís Sanchez Martin: Rocroy 1643. Vérités et controverses sur une bataille de legend . Revin: caligrafik 2007. - On the basis of French and Spanish sources, archives and literature, the French-Spanish team of authors draws a more differentiated picture of the course and outcome of the battle; with a - unfortunately incomplete and disorganized - bibliography.

- John Lynch: The Hispanic world in crisis and change 1598-1700 , Blackwell, Oxford 1992. ISBN 0-631-19397-9 .

- Georges Mongrédien: Le Grand Condé , Hachette, Paris 1959.

- Geoffrey Parker: The Military Revolution - The Art of War and the Rise of the West 1500-1800 , Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1988. ISBN 3-593-34365-7 .

- James Breck Perkins: The Great Condé , in: The English Historical Review 3 (1888), No. 11, pp. 478-497.

- Bernard Pujo: Le Grand Condé , Editions Albin Michel SA, Paris 1995. ISBN 2-226-07671-9

- Geoffrey Regan: Battles that Changed History (2nd ed.), Carlton Publishing Group, London 2002. ISBN 0-233-05051-5 .

Web links

Coordinates: 49 ° 54 ′ 21 ″ N , 4 ° 30 ′ 19 ″ E