Battle of Orbetello

| date | June 14-16, 1646 |

|---|---|

| place | before Orbetello , Grand Duchy of Tuscany , today's Italy |

| output | strategic Spanish victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 24 frigates 20 galleys 8 fires 4 flutes |

22 frigates 30 galleys 5 fires |

| losses | |

|

1 exploded |

1 frigate sinks |

Les Avins - Leuven - Tornavento - Guetaria - Fontarrabie - Corbie - Diedenhofen 1639 - Turin - Aire-sur-la-Lys - Honnecourt - Barcelona - Cartagena - Diedenhofen 1643 - Rocroi - Orbetello - Fort Mardyck - Dunkirk - Rethel - Bordeaux - Lens - Arras - Valenciennes - Battle of the Dunes

The Battle of Orbetello , also known as the Battle of Giglio Island , was a naval battle in the Franco-Spanish War . It was built on June 14, 1646 in front of the Spanish- ruled town of Orbetello on the Tuscan coast in what is now Italy between a French fleet under the Admiral de Maillé-Brézé , Duke of Fronsac and a Spanish fleet under Miguel de Noronha , 4th Count of Linhares, beaten. De Noronha had been dispatched to break the naval blockade of Orbetello and to free the city from the siege that had been sustained since May 12 by a French army under the command of Thomas Francis of Savoy . The Battle of Orbetello was quite unusual from a tactical point of view, as it was fought by frigates pulled by galleys in a light breeze.

After a hard but fruitless fight in which Admiral de Maillé-Brézé was killed, the French fleet withdrew to Toulon and left the sea to the Spanish, who decided not to pursue the French to free Orbetello. The Spanish land forces landed with the Count of Linhares a few days later, but failed in an attempt to break through the French lines, so that the siege could be maintained until July 24th. At this time another Spanish army arrived under the Marqués de Torrecuso and the Duke of Arcos, which had come from the Kingdom of Naples via the Papal States and on their way had forced the French troops to retreat with heavy losses.

background

In 1646, after some successes by the Spaniards in the Mediterranean , Cardinal Mazarin planned an expedition to conquer the Spanish- ruled Stato dei Presidi . This was intended to interrupt the Spanish lines of communication with the Kingdom of Naples and thus threaten the starting point of the Spanish military corridor, the so-called Spanish road. Pope Innocent X should also be intimidated, whose sympathies for the Spaniards Mazarin displeased. For this purpose, a fleet was assembled in Toulon under the young admiral Marquis de Brézé . It consisted of 36 galleons, 20 galleys and a large number of smaller ships and transported an army of 8,000 infantry, 800 cavalrymen with their baggage and their commander Thomas-Franz von Savoyen , who had previously been in the service of the Spanish Crown.

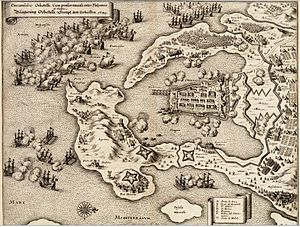

Orbetello was built on a spit between two inner bays of a large lagoon. Various fortifications created a strong defensive position: Porto Ecole in the east, San Stefano in the west and Fort San Filippo on the Monte Argentario peninsula, which is connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus. Ultimately, the French army landed at Talamone , where Brézé left half a dozen ships and galleys for the Prince of Savoy to bomb the city's fortresses. Meanwhile he went to Porto San Stefano with five frigates and four galleys and shot at the fort until they surrendered. After losing these positions, Don Carlo de la Gatta, the castellan of Orbetello, retired to the Hermitage of Cristo. The isthmus could be taken thanks to a battery that had been installed on the French galleys, and soon the lagoon was full of armed boats that Jean-Paul de Saumeur had gathered around him. Don Carlo de la Gatta, who was supported by almost 200 Spanish and Italian soldiers, had only a bad chance of long resistance without support. A relief force of 35 boats and five escorting galleys with ammunition and supplies, dispatched hastily from Naples, was defeated. A major fleet operation was therefore to be expected.

When the news of the siege reached Spain, Philip IV gave orders to assemble a relief fleet. Second hand goods were purchased in the Netherlands and special taxes were collected across the country. The supreme command of the expeditionary forces was entrusted to the Portuguese loyalist Miguel de Noronha, Count of Linhares , who was captain general of the galleys in the Mediterranean and therefore commander in chief of the Spanish naval forces in the Mediterranean. He was ordered to sail to Orbetello with 22 frigates from the silver fleet and the Dunkirk squadron. At least 3,300 soldiers boarded these ships to help with the relief. Linhares' deputy was Admiral General Francisco Díaz de Pimienta, who had recently withdrawn from the service, upset over his role as "eternal runner-up", by alleging health problems. While Linhares would be in command of the galleys, Pimienta would be in command of the sailing ships. As soon as the fleet was at sea, it merged with 18 galleys from the squadrons of Naples , Sardinia , Sicily and Genoa in front of the Sardinian Capo Carbonara , which increased the total strength of the fleet to 22 galleons and frigates and 30 galleys. Grand Admiral Jean Armand de Maillé-Brézé was able to be strengthened in the meantime by the divisions of Montade and Saint-Tropez , so that he could confront Linhares and Pimienta with 24 sailing ships and 20 galleys.

battle

At dawn on June 14th, the Spanish fleet headed for the island of Giglio , aft the galleons and galleys as vanguard and eight restrained ships that closed the formation. Admiral Brézé formed his fleet shortly afterwards in a line in which galleons and galleys alternated, and sailed westward in a gentle breeze to catch up with Linhares' ships. By 9:00 p.m., Brézé was within four miles of the Spaniards when the galleons of both fleets had to be towed from the galleys due to the calm while they waited for the wind to pick up. Brézé and his flagship, the Grand Saint-Louis, are at the top of the battle line, flanked by Vice Admiral Louis de Foucault de Saint-Germain Beaupré, Comte du Daugnon on La Lune and Rear Admiral Jules de Montigny on Le Soleil . The Grand Saint-Louis was from the galley cartridge under the command of Lieutenant General Vinguerre. 15 other ships formed the French battle line, each pulled by a galley. Montade's six-ship division was kept in reserve. Both fleets sailed alongside each other until Linhares, thanks to his larger number of galleys, was able to bring his ships to the wind and thus to keep on the French line. He tried to overrun the line and get caught between two volleys. Linhares had to pull Pimienta's flag galleon Santiago ; Don Álvaro de Bazán del Viso, general of the Neapolitan galleys, had the galleon Trinidad , the flagship of Admiral Pablo de Contreras, in tow and Enrique de Benavides, the general of the Sicilian galleys, towed other large Spanish galleons.

Brézé could not use his fire against the Spanish ships like he had done with his victories in Cádiz , Barcelona and Cartagena . So he pounced on Pimientas Santiago and riddled them with his artillery. The Santiago lost her main mast and was dependent on the assistance of Linhares and Pablo de Contreras. Fearing the French fires attack or being boarded by Brézé's galleys, Contreras covered the damaged galleon at the head of six ships while Linhares' flag galley hauled it out of danger. The remaining ships engaged Brézé in a fruitless battle that lasted until the two fleets parted at dusk. The Spaniards lost the frigate Santa Catalina , which had been set on fire by their own crew to prevent the French conquest after the ship was encircled by the French La Mazarine and three other ships. The frontline galleons Testa de Oro , León Rojo and Caballo marino suffered severe damage while a French fire exploded. Two French galleons were also badly damaged. The loss of life in the Spanish fleet is unknown. 40 men were killed or wounded on board the French ships. One of them was Admiral Brézé, who was crushed by a cannonball that struck the stern of his flagship Grand Saint Louis .

The following morning the Spanish and French fleets were 12 miles apart. Comte du Daugnon, Brézé's successor, decided to sail to Porto Ercole for repairs instead of chasing the Spanish fleet that had taken refuge behind the island of Giglio. Linhares chased him the whole of June 15th and half of June 16th. Four French supply ships, unaware of the departure of the main fleet, were caught by surprise by the Spanish fleet in the middle of the night, but managed to escape by following Linhares' maneuvers. The Spanish admiral finally gave up the efforts to free Orbetello. This had proven impossible because a storm that night had dispersed most of the ships. Some of them took refuge in Sardinia, others at Giglio or Montecristo . The Santa Bárbara galley sank off Giglio, resulting in the deaths of 46 rowers. The French also suffered from the storm. One of their galleys, the La Grimaldi, sank off Piombino , even though its crew and artillery were taken on board by the Spanish fleet. Another ship, the Saint-Dominique , stayed behind with a fire and was caught by Pimienta off Capo Corso.

Aftermath

On June 23, the Spanish fleet anchored off Porto Longone , where a council of war decided to relieve Orbetllo after the most important repairs had been made. Two days later various Dunkirkers were sent away to harass the port of Talamone and eight ships from Naples arrived in Porto Santo Stefano , destroying or capturing around 70 tartans and barges with supplies for Prince Thomas of Savoy's army. Meanwhile du Daugnon returned to Toulon. Despite its failure, supplies were later brought to Talamone on board five ships and Linhares' attempts to break through the French siege ring were unsuccessful. Linhares disembarked 3,300 soldiers under the command of Pimienta, who divided them into two corps and advanced on the French lines. The first group managed to take a hill on which a French cavalry attack could be repulsed, but the second group was defeated after a six-hour battle and forced to retreat onto the ships. 400 wounded were evacuated; the dead were left on the battlefield. The siege could not be ended until an army under the Duke of Arcos and the Marquis of Torrecuso stormed the besiegers' camp a month later, in which over 7,000 men were killed or captured and the entire artillery and entourage in their hands the attacker fell. This made the entire French campaign a failure.

Dissatisfied with the outcome of the naval battle, Philip IV , who had expected that the French fleet would be completely destroyed, which would have restored the honor of his navy, released the Count of Linhares, Admiral Pimienta and other officers, captured them and sued them Mismanagement and abandonment of their troops. Linhares was replaced by Luis Fernández de Córdoba, Pimienta by Jerónimo Gómez de Sandoval and Bazán del Viso by Giannettino Doria. Likewise, Philip IV appointed his 17-year-old illegitimate son Juan José de Austria to the Príncipe de la mar , the commander of all Spanish naval forces, and gave him extensive orders and powers to end the inadequate command of the Spanish navy. The French failure at Orbetello was instrumental in reducing French influence in Italy. As a result, 6,000 soldiers were able to be brought from Naples to Valencia to fight the French armies in Catalonia. In September, with the support of a French expeditionary force led by Armand-Charles de La Porte, Duc de La Meilleraye, the fortresses of Piombino and Porto Longone were taken, which led Francesco I. d'Este , the Duke of Modena to close his alliance with Spain end and turn to France.

literature

- Yves Marie Bercé: The birth of absolutism: a history of France, 1598–1661 . Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK 1996, ISBN 978-0-312-15807-1 .

- Jeremy Black: European warfare, 1494-1660 . Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-27532-3 .

- Cesáreo Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . 4th edition. Est. tipográfico Sucesores de Rivadeneyra, Madrid 1898.

- Jan Glete: Warfare at sea, 1500–1650: maritime conflicts and the transformation of Europe . Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-0-203-02456-0 .

- Arthur Hassall: Mazarin . BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009, ISBN 978-1-110-51009-2 .

- Tony Jaques: Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century . 2nd Edition. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9 .

- Charles de La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . E. Plon, Nourrit, Paris 1899.

- Fernando Martín Sanz: La política internacional de Felipe IV . Fernando Martín Sanz, 2003, ISBN 978-987-561-039-2 .

- RA Stradling: The Armada of Flanders: Spanish Maritime Policy and European War, 1568–1668 . Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-521-52512-1 .

- RA Stradling: Spain's struggle for Europe, 1598-1668 . Continuum International Publishing Group, 1994, ISBN 978-1-85285-089-0 .

- Stéphane Thion: French Armies of the Thirty Years War . LRT Editions, 2008, ISBN 978-2-917747-01-8 .

- Geoffrey Treasure: Mazarin: the crisis of absolutism in France . Routledge, 1997, ISBN 978-0-415-16211-1 .

- George Payne Rainsford James: The life and times of Louis the Fourteenth . HG Bohn, London, UK 1851.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 362 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 363 .

- ↑ Jaques: Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century . S. 477 .

- ↑ Glete: Warfare at sea, 1500-1650: maritime conflicts and the transformation of Europe . S. 184 .

- ^ Black: European warfare, 1494-1660 . S. 190 .

- ^ Rainsford James: The life and times of Louis the Fourteenth . S. 99 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 364 .

- ^ A b Treasure: Mazarin: the crisis of absolutism in France . S. 99 .

- ↑ a b Bercé: The birth of absolutism: a history of France, 1598–1661 . S. 184 .

- ↑ a b c Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 361 .

- ↑ a b c La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . S. 112 .

- ↑ La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . S. 113 .

- ↑ a b Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 360 .

- ^ Stradling: The Armada of Flanders: Spanish Maritime Policy and European War, 1568-1668 . S. 127 .

- ↑ La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . S. 114 .

- ↑ a b c La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . S. 115 .

- ↑ a b c La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . S. 116 .

- ^ Thion: French Armies of the Thirty Years War . S. 32 .

- ↑ La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française. S. 117 .

- ↑ a b c d Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 365 .

- ↑ a b c d Fernández Duro: Armada española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y de León . S. 376 .

- ↑ a b Stradling: Spain's struggle for Europe, 1598-1668 . S. 255 .

- ↑ La Roncière: Histoire de la marine française . S. 121 .